Steve Turtell's Blog

August 10, 2015

Her Name Is George

“All that is prearranged is false . . . . . How do I know what I think until I see what I say,”

E.M. Forster, Aspects of the Novel p. 101

In 1995, I was forty-five, in the MFA program in poetry at Brooklyn College, and teaching for the first time in my life. In the single class we had in how to teach basic composition, one of our assignments was a brief autobiographical essay. I wrote about my very first memory, of a nighttime sky glimpsed from within my hooded baby carriage. Even as an infant, I was so mesmerized by the beauty of a rectangle of liquid sapphire, that I have never forgotten it. After the class I put aside the essay, but it haunted me. It was the beginning of a memoir that I am now, nearly twenty years later, close to finishing. It has taken me that long to discover that all along, I actually was writing the memoir I needed to write, I just didn’t know it.

1964 – 2 years before coming out.

My first idea, right after grad school, was to write a straightforward autobiography, called Trying To Be Ordinary. The theme was my nearly always unsuccessful attempt to fight against the effect that being gay had on what might have been a simple life with a conventional trajectory: school, college, career, family, retirement. The longer I wrote the more I realized it was unsatisfying—mainly because it was becoming a standard gay memoir. Even in the late 90s I thought there were already enough of those, all of them centering on coming out.

1968 – Two years after coming out.

Then, realizing that I had to write about what was unique to me, it became an example of yet another over-populated genre: the trauma memoir. I had more than enough material for both of these memoirs, and there was clearly a market for them, but I stopped. I had trouble not only with the subject matter, but the writing itself. The tone was wrong. I couldn’t seem to escape the influence of many of the memoirs I’d loved, or resist the temptation to try to write as beautifully as some of my favorite prose stylists (typically, I love best what I can’t do well myself and literary dandies are my downfall). I kept falling into a grandiose elegiac tone. Also, it was all exposition, very little story, and most of it read like the things I removed almost without thinking from the poems I was starting to publish and that ended up in my first book, Heroes and Householders. Looking back, I realize I was teaching myself to write narrative prose.

I made slow progress. For a long time I couldn’t tell when something was getting better through revision, which was obvious to me in a poem Then, sometime in 2005 I had a better idea. I thought that I could split my life, as I had often lived it, into the two spheres of public and private. I would write two memoirs, one called Business Address, the other Home Address. I’ve had a zig-zag work life and several different “careers” although I never viewed them as anything other than a way to earn a living. But having been a lighting designer, a baker, a journalist, a teacher, museum administrator, and a fundraiser (among other things)—i.e. , had the kind of life I used to see written in thumbnail fashion on many author bios—I began writing what for the last three years I started calling At Work: Fifty Jobs in Fifty Years. Once I finished that, I thought I could tackle the more difficult, more personal memoir Home Address, but with a similar structure: a chapter for each of the 20 places I’ve lived: Brooklyn, Leonardtown Maryland, Manhattan, San Francisco, London and Key West. The structure for both would be the same: the memoir as picaresque novel, with frequent changes of scene, and a large cast of subsidiary characters entering and leaving my life, who would allow me sometimes to take the focus off myself.

By last fall, I’d written over 35 chapters for At Work, made notes for the remainder and published many of them on my blog (https://steveturtell.wordpress.com/) hoping to build an audience and possibly even interest an agent or publisher. I’d not written the chapters in chronological order. I wanted to generate the most variety by jumping around. But with the majority of my jobs covered, I thought I should begin to see how they stacked up as a single narrative.

When I put them in order and printed it out, I was distressed. Most of them were not narrative enough. And it was hard to see how I could produce a through line, an overall arc of meaning. This stalled me for several months. But one day, reading through the unwieldy manuscript yet again, I noticed something. The best chapters all concerned the effect being gay had on my work life. After getting expelled at 14 from a religious boarding school in 1965 simply for telling the headmaster I was gay (I was hoping to stop the constant harassment I got from another student) I became a gay activist and vowed I’d never hide who I was no matter the cost. I’d found my through line. And it wasn’t going to be a typical gay coming out memoir. Instead it would depict not just my life, but the life of the culture around me as it changed year by year, decade by decade. I dropped the title, At Work: Fifty Jobs in Fifty Years. Instead, it is now called “Her Name Is George”: Out at Work from Stonewall to the Present. The title is what I literally said to a young Latino I supervised in a bakery in 1976 when he asked: “So, Steve. You got a hot date tonight?”

“Yeah, I do.”

“Cool, man, what’s her name.”

“Her name is George.”

Twenty years after writing that first essay, five years after beginning the first of two planned books, I found my direction and can now see my way to the end. I’ve even written a dozen of the most important chapters, although they will all have to be revised. The best part of this, frustrating as it’s sometimes been (I’ve often wanted to give up) is that I couldn’t have planned it if I tried, any more than I could have anticipated my very first coming out, at the age of fourteen.But even then language itself, the power of a single word, was at the heart of the story.

To date, my blog has had over 8,000 visitors from 65 countries.

Active Voice – Steve Turtell on Memoir

by jessica • April 17, 2015 • 2 Comments

Active Voice is a new addition to Bunny Island Key West where writers discuss various aspects of the craft of writing. Sometimes this section will provide commentary on a particular experience, share hard won information on craft, or offer musings on the state of the art. Steve Turtell, poet, blogger, photographer and now memoir writer is my first invited guest blogger.

Steve Turtell is a poet who lives in New York City and Key West. His collection of poems, Heroes and Householders, was published in 2009 by Orchard House Press and was reissued in May 2012 in an expanded second edition. His 2001 chapbook, Letter to Frank O’Hara was the 2010 winner of the Rebound Chapbook Prize given by Seven Kitchens Press and was reissued with an introduction by Joan Larkin in 2011. He is currently at work on “Her Name is George”: Out on the Job from Stonewall to the Present, and Peter Hujar: Invisible Master. You can follow him on Twitter as @rdturtle and friend him on facebook.

(My review of Heroes and Householders can be found here.)

November 20, 2014

Mary Baker Eddy to the Rescue: Stealing Wheelbarrows at Carl Fischer Music Publishers—1973

PAUL AND I LEANED against the back wall at Tye’s on Christopher Street. He drank Bud Lights; I prepared myself for walking home in the winter cold by sucking down another Remy Martin. We chatted and lamented our respective vocations, his firmly established, mine potential at best. A successful composer, Paul had zero sympathy for the difficulties of writers, especially young, neurotically unproductive, unpublished writers. I kept a journal that was the equivalent of an emotional toilet (ET write home!) and squeezed out a poem once every six months. I hadn’t tried to publish any of them.

“Ever try to peddle a string quartet?” he asked.

Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic, and Seiji Ozawa and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra had conducted the premieres of two of his works; Boosey & Hawkes published them, and considering the twenty-six year head start—his forty-six to my twenty-two—I thought this a little unfair. But he did sympathize with my real concern—finding a job that didn’t eat up my life and leave me nothing left over for what I hoped would be my creative work. We’d been having this conversation since we met, while I was still at the Library on Wheels. The morning after our first date, he pretended to be my neighbor, called the library to say I was sick, so we could spend more time in bed. Our brief fling had developed into a friendship. We could even go out drinking and cruising together. Now that I was employed again, I could afford it. Mary Baker Eddy may not have converted any of the succeeding Glovers in our branch of the clan, but Divine Mind seemed to be on my side when it came to getting jobs, this time as stock manager at Carl Fischer Music Publishers in Cooper Square.

I loved walking to work—a mere five blocks away, and even coming home for lunch. But once I checked in each morning, looked at the stock list and began replenishing titles before they ran out, there was little to amuse me. Not even my co-worker, Willard’s gossip, made up for it. Willard’s best story concerned his youthful attempt to speak French at a dinner party. He took an older woman’s hand, kissed it and said “Je vous baiser, madame.” She slapped him so hard his ears rang for an hour and later his host explained that he’d just told her “I fuck you, Madame.”

The job did have a fringe benefit: I once traded stolen sheet music to my pot dealer, a classical musician, and I took home as many guitar manuals as I could. I used the same method as the construction worker who asks if he can have the dirt for his garden. Every night at the factory gate he pushes a wheelbarrow full of dirt. The dirt is carefully sifted for pilferage: nothing. The guard is certain the man’s a thief and promises not to arrest him if he will tell him what he is stealing. “I’m stealing wheelbarrows.” I’d asked the head manager if I could take home some of the empty delivery boxes. I planned to use them in my apartment renovation, and take out rubbish and plaster. I could carry three or four nested boxes in one neat stack. No one ever checked the bottom box, which had as much music in it as I could carry without giving myself away. Paul let me know he disapproved*, and besides, had no use for any of my stolen goods.

When not distracted by cute new arrivals, we talked about music. He explained, as if I could understand him, that the harmonics that thrilled me in so many Debussy piano pieces were often “thirteenths.” He also had great gossip about which famous musicians couldn’t sight read very well. Paul was in constant demand for his ability to play any piano piece set before him, even if he’d never seen it before. Some of the most famous concert pianists, he said, had practically to be spoon fed a new piece bar by bar. I remembered a friend who made his living tuning pipe organs disparaging a famous Bach specialist—“He couldn’t play Come to Jesus on whole notes!”—and now wondered if it was true.

When I was on about my third round, Paul suddenly had a brainstorm—it arrived from wherever is furthest away, and completely unconnected to the proverbial left field.

“I know what you should do to earn a living while you write,” he announced. “You should become an art restorer.”

Whaaa?

Talk about non-sequiturs. But I ran it by as a fantasy and to my surprise liked the idea. I saw myself, wearing an apron and latex gloves, bathed in sharp white, clinically pure light, in a neatly organized conservation studio in the basement of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I imagined gently dipping the edge of a pre-Columbian textile in a chemical bath, testing for ill effects before immersing the whole thing. The crisp light and a professional life spent with great art appealed to me the most. Not that I knew shit about any of it.

“There’s just one problem,” I told Paul.

He looked at me and I tried to focus. I was, as usual, a little drunk and on the way to getting truly tight. When I had enough of my blurry attention focused on him to talk I said, “I don’t have a BA. Won’t this require at least a masters?”

“So you finish your BA. Then you’ll go to the Institute of Fine Arts uptown. A friend of mine went through that program. You’ll like it.”

People with advanced degrees always spoke to me like that. As if it was just a matter of hanging around a university long enough to pluck one off the shelf. I suppose if you’ve already earned a PhD with a dissertation called “An analysis and comparison of the motivic structure of Octandre and Intégrales, two instrumental works by Edgard Varèse,” an MA in art history and conservation looks like a cakewalk. And he taught music composition at NYU so it all seemed more than plausible to him.

By the middle of January, I’d taken out several thousand dollars in student loans, and reenrolled in Brooklyn College for the spring semester as an Art History major. I’d like to say I was decisive; impulsive is more accurate.

The student loans allowed me leave Carl Fischer, but with the cost of books, rent, phone and Con Ed, cigarettes, top-shelf cognac, six-packs of beer, and gallons of cheap wine (I contain multitudes; unfortunately, they all love to drink and their tastes vary) before the semester ended I’d nearly run out of money, even with the additional income provided by silk-screening Claude’s pornographic stationary (see Claude’s Little Red Men). I now also had four incompletes on my transcript. But yet again, Divine Mind gave me a little push.

Manuel and some other friends performed several times a week in an off-off-off Broadway show called The Palm Casino Review, which Sheyla produced, with sets designed by Steve Lawrence, at the Bowery Lane Theater. During the intermission a handsome friend of Manuel’s asked me “What are you doing at night?”

“Nothing.”

“How would you like to run the lights for this show?”

Of course I said Yes.

Next up: “Camille’s Hairy Chest—My brief and dazzling ‘career’ as a theatrical lighting designer–1974”

* I have long since made amends for all my youthful theft. But I must still have something of the thief in my aura, because in any large department store, I can immediately spot the house detectives. They also notice me noticing them, and follow me for a while.

November 13, 2014

Shanti! Shanti! Shanti! Chaotic Vibrations at Ananda East Bakery — 1973

A LARGE BOWL of oatmeal raisin cookie batter slipped from my greasy hands and landed on my sandaled feet.

“Oh, fuck! Fuckity-fuck, fuck-fuck!”

I sat, massaged my sore toes, and reflected that “hopping mad” is not just an expression. Neither is “seeing stars,” as I discovered a few years later after a cast-iron basement door collided with my skull. When I felt able to stand and resume work, Bonnie, co-owner of Ananda East, admonished me: “Everything you say stays in the air as a vibration. So I would appreciate your not cursing.”

“Shanti! Shanti! Shanti! Is that better? It hurt!”

I’d started less than a week ago, but needless to say, Bonnie and I weren’t getting along. And back then it wasn’t always easy to get along with me. My inner brat had survived childhood—in large part because I was so angry. My late teens and nearly all of my twenties were the loudest “Fuck You!” I could deliver to anyone and anything I deemed an obstacle, a threat or an enemy—at times this included the known universe. I only discovered the concept of “restraint of tongue and pen” ten years later, and my ability to abide by that noble principle is still a work in progress. I admire the wisdom of Aristotle’s comment in the Nicomachean Ethics, that “anyone can get angry,” but that getting angry at “the right person, to the right extent, at the right time, with the right motive, and in the right way,” is difficult. At twenty-two I couldn’t have put that into practice even if I’d wanted to.

I felt certain that Bonnie and I’d manage to get along again as soon as the pain in my feet subsided. Of course, things got worse. Two weeks later, I participated in the third annual Gay Pride March. These events gave me a natural high and I was actually beginning to believe that things might change for gays and lesbians. Maybe not much in my lifetime, I figured, but I was hopeful. I’d walked alongside my boyfriend, Michael, two years earlier on the very first one. That was before his consciousness-raising group helped facilitate our breakup when they convinced him that our ten year age difference made dating me an exercise in “ageism,” a spurious charge. Michael was handsome and sexy; thirty years later one of the group admitted jealousy as the real reason.

Monday morning, the day after the march, I arrived at work eager to demonstrate how efficiently I could turn out trays of brownies, a few dozen Carrot Cakes and other hippy comfort foods. I entered the kitchen just in time to hear Bonnie tell a co-worker, “Well I think it’s disgusting. I don’t think families, and women and children should have to see things like that. “ Their immediate silence let me know, if I couldn’t have guessed already, what she found offensive. She turned away and served the customer who had walked in behind me.

And so, for the second time since returning from Fire Island I left a job—the first one at the bookstore after only a week, this time in less than a month—and counting both Down on the Farm and the Nelly Deli, by the end of June I’d had four employers in six months, and lived in three places.

My anger at Bonnie’s reaction to the Gay Pride March aside, I could no longer afford to work at the salary they paid. A small family business—both Bonnie and her husband worked there—giving me additional hours was out of the question even if I wanted to stay. Bonnie’s disgust made it easier to quit. I gave two weeks notice, trained a replacement, and began looking for a full-time job that would cover my rent and other bills before I depleted my remaining savings

Bonnie got her revenge two years later when I applied for and was hired as the baker for The Front Porch restaurant, a soup and sandwich chain with three restaurants in the city. I’d be working in their commissary kitchen in Gramercy Park. I came home thrilled that I’d yet again found a baking job that did not require me to join a union, and was relaxing when I got a phone call from the man who’d hired me.

“Mr. Turtell, this is Mr. Eames. We’ve checked your references and we don’t want you to work for us.”

“Excuse me? Who did you speak to?”

He was obviously reading from my resume when he replied, “We spoke to someone at Paradox Bakery and they told us your work was shoddy and erratic and that you showed up late or sometimes not at all.”

“You spoke to someone at Paradox? Who did you talk to? They’ve been out of business for two years.”

“My assistant spoke to them, she knows who she spoke to.”

“Well, I’m sorry you don’t want me to work for you. I’m a good baker. I think you should know that none of what you’ve been told you is true.”

“Thank you Mr. Turtell. That will be all.”

He hung up and I wondered what could have happened.

There was only one possibility. By then I had three baking jobs on my resume, Paradox, a health food bakery near Columbia (where I’d pissed off everyone else who applied by telling them they should stop wasting their time and go home, I was getting this job—which I did), and Ananda East. Ananda was still in business and before submitting the resume to The Front Porch, I’d called to verify the phone number and to make sure Bonnie was there. I called her again.

“Bonnie, did you just provide a reference for me to the Front Porch?”

“Yes, the woman who runs it is a friend of mine and I spoke to her.”

“What did you say?”

“I told them you have chaotic vibrations.”

Chaotic vibrations. Not good vibrations. Good vibrations were still all the rage. I’d never known them to be a job requirement. Nor did I know what the fuck she meant. I hadn’t been crazy about her vibrations either. Somehow she and her husband had managed to reconcile their puritanical Irish-Catholic upbringing with a new-agey Eastern somethingorother and wind up quite pleased with themselves. When I’d complained to my old boss David, who’d paid me a decent salary at Paradox, that I couldn’t afford my rent on the pittance Ananda paid me, he said “They want you to work purely for the spirit of the thing: which is money. Theirs, not yours.”

“Bonnie, I know how to bake. I did a good job for you at Ananda.”

“I told her all that too.”

“Well whatever else you told her, it just cost me a job I need.”

I owed a couple months rent, hadn’t paid my phone bill and Con Ed was threatening to cut off service.

“I think you did that yourself.”

I hung up. She always was smug. But to be fair, I was very much the Angry Young Man. Enraged Young Man is even more accurate. I sometimes shook, unable to control my fury or my voice, and could not trust myself to be rational. My outbursts were textbook examples of “intemperate” and no one was safe from a scathing denunciation. Sometimes I could walk away. All too often I didn’t and said something both unforgivable and unforgettable—the unforgettable aspect was a goal I set for myself and at times mentally rehearsed for.

And, in retrospect, Bonnie was right. I did have chaotic vibrations. Over the next few years, as I bounced from job to job, one week a baker, the next month a theatrical lighting designer or a temporary typist, or a housecleaner, my ability to do a good job was not always under my control. At the beginning of every new job I seemed to test the limits of my employers, going just up to and sometimes over the line that would get me fired. I had no patience and forced people who hired me to exercise all they possessed of that underrated virtue. What saved me, I now realize, is that despite my faults, I worked very hard. I said as much in the interview for my next job. The owners of Carl Fisher Music Publishers were Christian Scientists. I have a tenuous connection to Mary Baker Eddy, as her first husband, George Washington Glover, was my mother’s great uncle, or maybe it was his son, George Washington Glover, Jr. I’ll have to find out for certain one of these days. But I’m certain that the president of the company hired me mainly because he believed me when I said “I’m a hard worker.” I saw a much needed paycheck in my future when he replied: “I’m sure you are.” But it can’t have hurt that I mentioned my connection to Ms. Eddy.

Next up: Mary Baker Eddy to the Rescue: Stealing Wheelbarrows at Carl Fischer Music Publishers–1973

October 23, 2014

Reheating a Souffle: The Nelly Deli Redux – 1973

(Image courtesy Kahh-poww at Deviant Art)

NONE OF US KNEW WHAT, but something had crawled up Dutch’s ass sideways and started banging on his solar plexus from the inside. The staff got daily updates on the status of his discontent. He berated waiters, told the cook the food was disgusting and boring (well, he may have had a point there, but frozen meat patties are not famous for their versatility) and asked me why I used so much dish washing liquid.

“What do you do, drink the stuff?”

Looking back, I wish I had said: “Well, perhaps you like owning Cherry Grove’s only greasy spoon, Dutch. However, cute as that expression is, no one wants utensils so sticky they feel like sex toys.”

The French have an expression for it: l’esprit d’escalier. Does it apply to things I wish I’d said forty years ago? I held my tongue for a change, but wondered if I’d made the right move leaving The Front Porch. There I could call myself a cook; here, back on Fire Island, I washed dishes again at the Nelly Deli, as I had last summer. It seemed a reasonable price to pay for living rent-free in an expensive resort.

We soon found out that Dutch’s twenty-something nephew was the instigator. We were only one month into the season and over the first hump, Memorial Day, when the nephew announced that George, who rehired me on the spot when I showed up unannounced at the end of April, had “left” to make way for “new management.” The nephew saw more promise in the Nelly Deli than anyone else could and announced that he intended “to make my first million before I’m thirty.” He swanned around with his handsome, bodybuilder boyfriend, and introduced the “new management”—a middle-aged, southern gay couple. One oversaw the day shift; the other took the night. They looked alike, dressed alike, were tall, thin, bitchy in a polite, pseudo pleasant manner and smiled all the time.

“Well I guess I never knew how hard it was to properly wash a dish!” one said while chuckling and holding up a plastic plate, angling it under the fluorescent light, clearly seeing something invisible to me but that no competent dishwasher, human or mechanical, would have left. Appearances were their main concern as not much could be done quickly with the décor, menu or the quality of the food. They made things miserable for anyone they didn’t like and wanted to get rid of, and the kitchen rumor mill (all five of us) churned with the names of the new managers’ unemployed but very cute young friends. Cuter than us anyway.

They were very good at it and we were all unhappy soon enough. The waitress Maria was the first to go. She came up to my chin, had caramel skin, a halo of tight black and grey curls, and was so clearly butch I almost found her sexy. I envied her mouth. She talked back to the nephew, and up and at the managers. Maria also had a girlfriend who could take up the slack if she quit, which she soon did. To date she is the only person I’ve ever heard say: “You can take this job and shove it.” Her more colorful version was “Fuck you and this fucking job. Who wants to work in this shithole anyway? I’m outta here.” And out the door she went.

I missed her and her sanguine approach to most things, including her relationship. When a couple she knew broke up, I asked her if she ever worried about that herself. Nope. “Well, if she falls in love with someone else, that’s the ballgame isn’t it?” She laughed, winked at me and went back to the dining room where her banter with the guys earned her excellent tips.

“And what are you sluts having tonight? Will it be Beef in Bondage or Chicken in Chains?”

“Ordering for a Bitter Party of One!” she shouted into the kitchen loudly enough for the “party” to hear. She’d find another job easily. The new managers, to no one’s surprise, had a handsome young friend waiting and eager to take hers. He appeared the next night looking like he was moonlighting (or maybe just auditioning for) The Sea Shack. Tall and muscular in the restrained manner of a dancer, he wore pressed chinos and a starched white shirt. His neatly parted hair looked like it had been just combed with water—an effect that lasted his entire shift. I had a ponytail that reached to my shoulder blades, two pierced ears, and wore a tank top, shorts and flip-flops. My days were numbered.

I hung on through the first week in June, but fortunately had taken precautions. I’d saved everything I earned in May and right after Memorial Day had gone back into the city to sign a lease on an apartment—an odd y-shaped tenement on the corner of E. 10th Street and 1st Avenue. I gave the landlord $220–two months rent—and planned to work on it all summer long on my days off. I looked forward to the end of the season when I could move into a freshly painted and decorated apartment all by myself. I was sick of roommates. A month away from my twenty-third birthday, poor, not quite homeless, I lived in the same damp, moldy room under the Sea Shack I’d had in the fall. This time I shared it, with a noisy, radio playing Latino waiter whose deep respect for restaurant hierarchy made it even more unpleasant—as the lowest man on the shortest totem pole in all of Cherry Grove (even the boy-maids at the Cherry Grove Inn had their own rooms), I came last. He demanded I vacate the room whenever he had a “date.” I spent more hours outdoors than I wished to, but my primary pleasure was reading, and ocean waves as background were preferable to grunting, heavy breathing, Spanish dirty talk, and disco music.

To no one’s surprise, new management soon found my dishwashing skills wanting—and predictably they had a superior candidate lined up, one who would be as sparing of liquid soap as I was profligate. I suspected what they actually found wanting was any desire to socialize with them, still less to sleep with either, but they may have assessed my performance accurately. It’s hard to put your heart and soul into scrubbing aluminum pots, plastic plates, and tin “silverware” while subsisting on tuna, PB&J and the occasional cheeseburger. I’d been expecting this from the moment they arrived, and was amused to remember that only seven months ago I’d enjoyed the job. Another useful French expression comes to mind: I was trying to reheat a soufflé, or, given the milieu, re-scramble the eggs, since a soufflé was the last thing you’d ever find on the menu at the Nelly Deli.

The apartment in the city was my escape route. Within a week, I surrendered. I announced one morning that I wasn’t coming in, packed a single shopping bag each of clothes and books and took the next ferry to Sayville. By mid-afternoon I had moved back into Manhattan.

I quickly found a job at the Fourth Avenue Bookstore, around the corner from The Strand. When most of my first week’s paycheck went for a hardcover edition of The Complete Works of George Eliot, I realized I couldn’t keep that job if I hoped to pay my rent. Yet again salvation arrived, this time in the form of my second baking job. An ad in The Village Voice led me to Ananda East Bakery, on West Fourth Street, near Sheridan Square.

I’d baked at Paradox Bakery, cooked at The Front Porch, and washed dishes at The Nelly Deli: I grandly viewed myself as an experienced kitchen worker. Ananda’s owners, two former Boston Irish-Catholics who had morphed into devotees of an Eastern religion I knew nothing about, happily agreed. They knew Paradox Bakery and I had no doubt I could make Bonnie’s Carob Brownies and Oatmeal Raisin Cookies. I mastered the job quickly—and we were all happy for the first week. They didn’t pay much—not as much as I really needed even with a low rent: $110/month. I hoped I could negotiate a small raise once I’d proved myself. Then one morning, my fingers greasy with cookie batter, I dropped a large mixing bowl onto my sandaled feet.

Next Up: “Shanti, Shanti, Shanti!” How to Use Prayer Words to Piss off Your Employers at the Ananda East Bakery-1973

February 7, 2014

Where You Eat – Short Order Cook at Down On The Farm – 1973

Everything I need to know, I learned in a kitchen: e.g., how to give your boss a snow job; not to give another kind of job to a co-worker.

Tachi, the sexy Cuban dishwasher, leaned back against the slop sink and stared at me. I stood by the oven and stared back, unable to say anything. His amusement at my discomfort didn’t help. He was like a cuter, younger version of Fidel Castro, whom I’d never thought sexy before. He was a problem: a new bout of infatuenza I needed to squelch but that he knew instinctively how to inflame. As I cooked, I could often feel him looking at me from behind. I gazed at a sauté pan and, instead of burning mushrooms, saw his long-lashed, liquid opal eyes, thick glossy hair brushed back from the smooth forehead, his sensual, somewhat insolent, purple lips.

“What are you going to do?” Tachi asked.

“Do?”

“With all that feeling?” he teased.

Before I could answer, Noberto, the Argentinean waiter/busboy, rescued me. He glanced at us, smirked and pinned an order in the window. Table of five: one half chicken with apricots, brown rice and steamed vegetables; two filet of sole; one vegetable lasagna; and one sautéed “vegetable medley” over kasha. Determined to master the art of short order cooking, and prove to Charles the owner, that he was smart to hire me, I turned back to the stove. I scanned the dishes, broke them into components, started what took longest, and then went in descending order. I needed to ignore distractions like Tachi. Half-roasted chickens saved me. They needed more time in the oven. I needed to redo the mushrooms, and pressure cook another batch of brown rice. The béchamel was running low and Noberto swung by with three new orders.

When I took the job—more accurately, when to my astonishment Charles hired me after the most bizarre interview I’ve had to date, forty years later—my only problem was a lack of experience, which Charles, sweet generous Charles, allowed me to gain. He had no reason to.

Down on the Farm owed its popularity not just to the excellent food, but to the welcoming atmosphere created by Charles and his Argentine lover and co-owner, Roberto. They served a cross between Roberto’s Argentinian home cooking and Charles’ recent updates to his former macrobiotic regimen—he now allowed himself and his customers poultry and fish. Charles and Roberto liked to mingle with their customers. They sat at various tables when there was a free chair or crouched for a brief chat, and treated their two small rooms as their home. Noberto the combination waiter/busboy kept things moving. The clientele included many artists and theater people, some of whom lived in nearby Westbeth, and Noberto knew how to seat them to greatest effect. There was a framed letter from Ridiculous Theatrical Company founder and star Charles Ludlum hanging just inside the front door. Richie and I ate there frequently.

One night, Charles told my roommate Richie that their short order cook had just given notice and they needed someone to start in week. To my surprise, and without asking first, Richie announced: “Steve is an excellent cook and baker, hire him.” This wasn’t pure altruism. Much as Richie liked to meddle in his friends’ lives, he had what Sydney used to call “an inferior motive.” I had money troubles again. The modeling jobs were coming less often and clearly would soon stop altogether, while the need to pay my share of the rent would not. If I didn’t get a job, Richie’s planned winter trip to Peru with one of our roommates, Joan, might be cancelled. I knew a few things, but I would never have called myself a skilled cook, still less a chef. My only question was could I do it?

Charles didn’t seem to need more convincing; I met with him the next day and he took me into the small kitchen—except for the professional oven and range, it was not much bigger than ours on West 104th. The sink was behind me; the stove sat to the left of the butcher-block counter, where I could chop vegetables. A pressure cooker rattled as we talked and Charles said they served so much rice it had to be going all the time. I’d never used a pressure cooker and it scared me.

One by one he went over the dishes on the menu. I’d never cooked most of them. I saw the job disappearing if I admitted my ignorance.

“Charles, I’ve eaten here several times now. You have a regular clientele; they expect their favorite dishes to taste the same each time. Why don’t you show me how you prepare each one and I’ll make sure that there’s continuity before introducing any variations of my own.”

I know Charles wasn’t stupid. He dealt shrewdly with the more outlandish pronouncements of his favorite customers—this was the 70s, people were claiming spiritual enlightenment at a rate that would have made the Buddha proud. Charles ended all such speculative discussion with the catch phrase “But who knows what the reality is?” I admired his ontological agnosticism, but didn’t doubt his ability to tell the difference between vegetable stew and the big pot of bullshit I’d just handed to him. Maybe he admired my shameless attempt to manipulate him. Whatever his reasons, he did as I asked and all but cooked each dish for me, miming the action when he couldn’t use the results later, as he could when he put several half-chickens in to pre-roast and whipped up a gallon of the sauce I would soon be spooning over side orders of brown rice, kasha and pearl barley. I’d never made a Béchamel which he clearly guessed upon seeing the blank look on my face when he told me “We serve Béchamel sauce on just about everything; we just alter the flavor if it’s going over grains or on fish or chicken.

I said nothing.

“Béchamel. A white sauce?”

“Yes, Charles, I know what it is, but I want to make sure I make it with the exact thickness your customers are used to.”

He couldn’t have been fooled. God love him, he gave me the job. It was on this job that I made up what has become my life motto: Dive in; don’t drown. What I hadn’t anticipated was that I’d be learning how to negotiate some of the rougher waters of physical, but not emotional and spiritual attraction with someone I saw six days a week. Cooking was easy compared to this.

Down on the Farm had less than twenty tables. Most seated two or four, but a few sat six and there were times when eight were jammed together at the biggest, round table. Larger parties required two or more tables shoved against each other. No matter how large the group, they all expected their food to arrive at the same time.

During three or four seatings in six hours, I sometimes put out a hundred covers of the eight entrees on the menu. For the most part, I prepared them entirely myself, but Charles sometimes took a break from clomping around the dining room in wooden clogs and helping Noberto to bus tables to make sure that we had enough of our biggest staples: Béchamel sauce that we mixed by the gallon or the beans, chick peas and especially the brown rice that we cooked in twelve minutes—less than half the usual time—in the pressure cooker sitting on the back burner. On the busiest nights we filled the 1970s, i.e., pre-Cuisinart, pressure cooker four or five times. The two-gallon, hissing, rattling, damned near dancing, always threatening to explode, scare-the-hell-out-of-me monster, made it possible to serve fluffy rice with our broiled filet of sole or roasted half-chicken with apricots. Gummy rice, the hallmark of bad “health food” cooking, was not on the menu.

And fortunately, I discovered there is a kind of Zen secret to short order cooking. In less than a week at Down on the Farm, I felt like the centipede who couldn’t walk if he stopped to examine how he did it. The rhythm of the evening helped. Orders came into the kitchen at an accelerating pace. The quieter hours between six and eight allowed me to build up to the two-hour rush that followed. When the dinner shift ended, or was just coming to a close—when Noberto locked the front door and no more orders would be posted—I sang from the sheer relief of having gotten through another night. I was still far from being a skilled cook, but each successful night diminished the fear that Charles would regret hiring me in the first place. My relief, however, was tempered by the intensity of my feelings for Tachi.

Three weeks in, by which time my confidence had increased so much I relaxed enough to sing while I cooked, I was halfway through a rendition of Cole Porter’s Anything Goes, when Tachi asked me for a date.

“We’re closed on Sunday. I’m having a small dinner party, would you like to come?”

“Who else will be there?”

“It will be very intimate. Just you and me.”

I said Yes, and asked, like the well-brought up boy that I was, if I could bring anything.

“Just your own sexy self.”

Dinner did not go as Tachi had planned. As soon as I arrived at his Greenwich Street apartment, just a few blocks from the restaurant, he began plying me with a new, and very sweet drink he had invented for the occasion and that he called “La Principessa”— heavy on the dark rum, heavier on the gin, and made somewhat palatable by the sugar, orange and pineapple juice. Getting me drunk was easy, getting me into bed not so much. Especially after my first trip to the bathroom, halfway through the main course (chicken with black beans and rice—Tachi was a good cook), where I saw the note written on the mirror. I stared at it as I washed my hands:

“Steve = love.”

Oh dear. Even in my drunken state I knew, instantly, that what I felt for Tachi wasn’t love. It was an irrational mix of lust, curiosity, and need—need for the attention he gave me at work, an attention that lessened my insecurity, however awkward it made me feel, but also a need for simple physical contact, as I still had not had a relationship that lasted longer than two months. I wouldn’t fall in love—unmistakable, insane, suddenly in a new universe that still somehow looks familiar, life changing love—for another four years, when I was twenty-six. Looking at Tachi’s note I felt dishonest and cheap and a little bit mean. How much had I led him on? I didn’t know. I did know that I’d done it before.

At the Nelly Deli, I also used to sing when I worked. One night a waiter came into the kitchen just as I was beginning a lovely Judy Collins song, Since You’ve Asked. It was quiet in the dining room so he stopped to listen and I sang it right at him. The next night he told me how much he had loved the song. I thanked him casually, and went back to washing the dishes. He looked deflated and was brusque with me for several days. When I’d had enough, I asked why he’d suddenly turned on me: “We used to get along so well.”

“Why did you sing that song to me if you didn’t mean it? I thought you were singing it to me.”

Yes, I was that stupid and blind and self-absorbed. And as far as relationships went, I was twenty-two going on twelve. I’d had three “love affairs”—all with older men. In descending order, two months with a forty-nine year old poet whom I saw during the two-year interregnum of his now fifty plus-year relationship with a novelist; three or four dates with a thirty-four year old bisexual novelist who published his first book, about an affair with an older woman and then married one shortly thereafter; and two months with a twenty-eight year old gay activist. I remained friends with all but the novelist. I was not marriage material. I was not even boyfriend material. But I was willing to learn and I was now learning that there are some things you just don’t do where you eat. So I left Tachi’s house still on my feet, more than a little drunk, but pleased that I had put a stop to something before it got really ugly. Work was, as it had been at the Nelly Deli, a little tense for a while, but the awkwardness passed. It always does.

I’ve had several refreshers since. My realization that I had allowed this to develop was powerful enough to keep me in check for many years. It taught me not to play with people’s affections and to at least try to see the effect I had on other people. At twenty-two, it was still news to me that I had any.

December 12, 2013

The Concept of Irony at The Nelly Deli – 1972

Cabin in Oakleyville (forty years later)

“Into each life, a little privilege must fall.”

When the bakery closed in June, I was once again unemployed. I didn’t care. My Paradox paycheck kept me from spending all of my tax refund. Working two jobs in April had allowed me to save close to $300. Richie and I paid $44 each—only $10 more than on MacDougal Street—for our illegal sublet, which had an actual bathroom, not the hallway water closet I’d shared with my next-door neighbor. This, at twenty-one, was both luxury and financial security. I took long, hot showers; I no longer had to squeeze into the kitchen tub or hope there was toilet paper in the unheated water closet. I had enough money to last through the summer and maybe into the fall if I was careful. I was bound to find a job by then.

By August, still jobless, I accepted Manny’s invitation to visit for a couple of weeks in Oakleyville, the second oldest settlement on Fire Island. He offered to share the refurbished tool shed behind the house Steve Lawrence rented each year. It sat within smelling distance of the outhouse. Steve and the other occupants of the main house—his new boyfriend George, and guests like Peter Hujar, photographer Sheyla Baykal and her new Portuguese boyfriend Antonio, also had to step outside for their necessities, including the outdoor shower on the small back porch. But then, everyone in Oakleyville enjoyed a deliciously primitive lifestyle.

Too small to be called a town, a village, or even a hamlet, Oakleyville is located on the bay side of the island between the Sunken Forest and Point O’Woods. A history of Fire Island describes it as a “tiny community of ten houses, no store, no ferry, no water supply except individual wells, and no services.” In other words, Hippy Heaven circa 1972. It’s invisible from the beach. You have to know the exact cut in the dunes that leads there to find it. Maps of Fire Island still don’t list Oakleyville; even today, the tiny clump of houses that show up in Google Earth’s satellite view can be mistaken for an extension of Point O’Woods, with which it shares a post office.

On Tuesday, August 1st, 1972, Manny met me in Sayville, Long Island, where he had arranged to pick up his unemployment check. He’d somehow managed to convince the New York office that he was on Fire Island looking for work as “a dance and yoga instructor.” I suppose they accepted it because his benefits came from working as a principal dancer with the Nikolais Dance Theater. After a twenty-minute ferry ride over the Great South Bay, we arrived at Cherry Grove and walked further west along the beach with our leather satchels, knapsacks and shopping bags full of groceries purchased at the Sayville supermarket. We avoided the store in the Grove, which everyone called Tiffany’s (with good reason: shipping costs added so much to prices that before the summer ended I paid almost $1.00 for a single apple). A half-hour later Manny led us through the cut in the dunes and we stepped onto wooden planks leading back to Steve’s house.

If ever my life has had a Kismet moment, this was it. Other than two daytrips, I did not leave Fire Island and return to the city until the middle of October. Although I was a poor, technically homeless hippy, for the next two and a half months, I had a life of privilege and, albeit rustic, luxury.

One day I’m living in six-story high-rise on Riverside Drive. The next I step into a world right out of the pages of The Whole Earth Catalog, everyone in Oakleyville ready to pose for the illustrations. I bought the first issue and spent hours poring over it in my bedroom when I still lived with my parents in Brooklyn. I dreamed that one day I’d live in a commune, grind my own flour, buy brown rice in 50lb bags, and read every color of Andrew Lang’s Fairy Books while waiting for the bread dough to rise. I walked into a world I’d already imagined.

Oakleyville expanded my horizons socially and culturally. While not a commune exactly, Steve’s house was the center of a small ad hoc artist’s colony. The sculptor Paul Thek rented a house that sat directly on the bay. The art dealer Sam Green’s grand house—he’d installed electricity, running water and indoor plumbing—was opposite Paul’s. Peter Hujar visited frequently, staying with either Paul or Steve. Other regular visitors included the painter Ann Wilson, curator Sam Wagstaff, and Sam Green’s more glamorous guests. Sam played host to singer-songwriter Peter Allen—when he was still married to Liza Minelli—director John Schlesinger, Pace Gallery director Fred Mueller, and in later years, since Sam was one of the most successful, if eccentric, social climbers in New York, Greta Garbo and Yoko Ono.

This small community welcomed me in. Everyone loved the rice bread I’d brought from Paradox—a name that carried some cachet—and I’d already worked for Steve Lawrence that winter at the Cockette’s opening, so I was not a complete stranger. We all shared the chores and when Sheyla, who had a bit of the den mother about her, raved about a sautéed vegetable dish I’d cooked, I felt completely accepted. I could contribute to the household and I also knew a bit about art and books, the main topics of conversation at dinner. I had aspirations as a poet and while at Brooklyn College had read Susan Sontag’s Against Interpretation and the art criticism of Howard Rosenberg. I visited art galleries regularly and I’d seen the landmark 1969 exhibition, New York Painting and Sculpture: 1940-1970, at the Metropolitan Museum over a dozen times. I knew most of the names bandied about at the dinner table, but they spoke of them as their friends and colleagues, and they used first names.

Sheyla was divorced from the poet Frank Lima, had been painted by Alex Katz, and knew all of the New York School writers. Sontag had dedicated Against Interpretation to Paul Thek. Peter Hujar’s portrait of Sontag was on the dust jacket and he had taken part in Richard Avedon and Marvin Israel’s famous 1967 Master Class. Sam Green seemed to know everyone and had arranged Warhol’s first museum exhibition at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Philadelphia. Socially, Oakleyville was sometimes a heady experience, and I was dazzled. But that wasn’t what I loved the most.

After I’d lived there for only a week, the landscape began to work its magic on me. The beach on Fire Island was the most beautiful I’d ever seen, especially the long stretches of it between towns. When I walked along the shore I sometimes didn’t see a single house, or at most a speck on the horizon. I saw only the most simple and primitive beauty: sea, sand and sky, with a soundtrack as elemental—sharp, clipped seagull cries punctuating the rounded hush of waves hitting the shore, which diminished to a distant, mysterious whisper as it drifted back to the bayside houses and accompanied me into sleep each night.

Day by day the memory of the city receded. Time slowed; life was reduced to basics. The sea air sharpened my appetite and increased my hunger. Food tasted better. The day’s rhythm was no longer determined by a clock or a watch, which I don’t remember anyone wearing. The position of the sun overhead became the main timekeeper, second only to my growling stomach after an hour of body surfing. Lunch was followed by a nap that began with a paperback, its pages floppy soft from years in the salt air, falling soundlessly to the floor. At night, after a communal dinner, we sat on the porch of Steve’s house. Antonio’s guitar provided most of the music—Steve kept a transistor radio above the kitchen sink but we rarely turned it on. At the end of each nearly identical day, sleep was a long dreamless slide from nighttime to morning—something I’d not experienced since childhood when I used to feel as if I’d been dropped down a gently curved chute and I popped out fresh and alert into morning light. It was so easy and pleasant and cheap and luxurious all at the same time—and it was simple and unhurried. There were occasional trips down to Cherry Grove or the Pines for tea dance on Saturday or Sunday, but even these reminders of city life didn’t alter the sense of living far away from New York, although we were only a few miles off the southern shore of Long Island and sixty miles from Manhattan.

The single 10’ x 15’ all-wood structure Manny and I shared and slept in had a cot, a Bunsen burner, a five-gallon water jug we refilled with Steve’s garden hose, and a single kerosene lantern borrowed from the dozen or so that lit the three rooms of the main house.

The shed was a tight fit even for one, so I stored my sleeping bag under Manny’s cot every day. I didn’t mind. Growing up I’d shared a room with my older brother, and since leaving home had always had roommates. What I’d never had was an extended stay at the beach.

My father’s gambling never left us destitute—we always ate, and somehow my mother managed to dress us so that no one would ever suspect how little she’d spent. But we sometimes didn’t have a phone or a television and there was no money for vacations other than a single weekend each in Atlantic City and Washington, DC, and two weeks at a lakeside summer camp run by the Salesian Brothers in Goshen, New York, when I was nine.

Until I went to Fire Island for the first time, all I knew of beach life was the occasional day trip to Coney Island or Riis Park, and infrequent summer passes at Farragut Pool, a kind of working class country club in East Flatbush. Farragut featured an Olympic-sized pool, picnic tables, and handball and basketball courts, set on an entire city block, two acres of concrete. Tall box hedges inside a chain-link fence provided privacy and the only greenery; infants sat in the only sand—a ten-by-ten wooden enclosure that looked like a giant kitty litter and was as unappealing as the shallow end of the pool, where the kiddies often stained the water lemonade yellow.

In Oakleyville I slept and read and swam and cooked and ate and slept and read and swam and cooked and ate, and two weeks effortlessly stretched to a month.

I didn’t want to leave Fire Island and knew I’d overstayed my original invite, but Manny didn’t seem to mind—he frequently slept in the main house anyway, when Steve’s newest boyfriend George was in the city selling drugs to rock stars.

One day near the end of August, while Manny and I were visiting friends of his in the Grove, I called Richie. He’d found another roommate—but worried that as illegal tenants they’d be forced to leave. I could move back in with them if I returned, but I was now, in a casual, somewhat privileged manner, homeless, living on a resort island, and running out of money. As he had earlier that summer, when he got me into modeling for art classes, Manny had a solution: look for work in Cherry Grove, where they sometimes provided room and board.

I walked back down to the Grove a day before the beginning of Labor Day weekend.

I stopped at the Sea Shack first. They did not need my services at Cherry Grove’s only white linen tablecloth restaurant. Even if I’d had any experience, one look at the tall, well-groomed, handsome waiters, some of them professional dancers, all of them muscular and tanned under starched white shirts and pressed aprons, told me why. Nor were there any openings at the Cherry Grove Inn, the Cherry Grove Beach Hotel, or the grocery store.

My last stop was the Grove’s greasy spoon just off the pier. No one used the official name, the Dock Bar and Grill. Everyone called it “The Nelly Deli,” and it served as an unofficial reception area for the ferries. People lounged at the picnic tables in the fenced-in patio as they waited for guests to arrive or depart, or stopped in for a quick meal. I never saw it empty, and sometimes at breakfast you had to wait for a table, since so many guests at the Inn and the Hotel ate there. Maybe they had a job for me.

The screen door squeaked on rusty hinges. When it slapped shut behind me, I was transported back to the tiny cafeteria at Farragut Pool. I felt the same delicious transition from sunlight and noisy crowds to cool shade, heard the hiss of burgers on a grill, and breathed in the heavy oily smell of cheap French Fries. Red and white “gingham” oilcloths covered the tables, each set with a metal napkin dispenser, red and yellow plastic catsup and mustard bottles, and black and white plastic salt and pepper shakers. I felt at home.

Jimmy, a beefy, straight, married man who commuted from Sayville, managed the place for owner, Dutch Wavering—one of the Cherry Grove’s largest landlords. Dutch’s claim to fame was that Mary Astor, whom I had never heard of, was his godmother—it was the first thing anyone mentioned about him.

Jimmy said I was in luck. One of the dishwashers had just quit, and as more and more people streamed off now every half hour ferries for the busiest weekend of the year, he needed someone in the kitchen immediately.

I put on an apron and pink rubber gloves to begin my new job as a part-time dishwasher. Waiters rushed in to dump the plastic plates and cheap cutlery into a grey rubber bin while Jimmy explained the terms.

I could work off the books. He could pay me a dollar fifty an hour, plus a room under the Sea Shack and part-time board (tuna and or PB&J sandwiches mostly) on the days I worked—Thursday through Monday afternoon—a busy day since most hairdressers had Monday off and didn’t go back to the city till evening. The terms were more than agreeable to me.

After that first shift, I walked back to Oakleyville. I told Manny the cabin was all his again. He had never complained but I knew he’d enjoy not having to share such a tiny space for the remainder of his stay. I packed up my satchel and until the Nelly Deli closed for the season in the middle of October, I lived in Cherry Grove.

By evening I’d moved into one of the cabana-like rooms in the unheated, damp and moldy warren under the Sea Shack. I only planned to sleep there and considered this a deal. From Thursday to Sunday, I worked from four pm until midnight, and then again Monday morning to afternoon. Jimmy frequently kept the place open longer if there were customers, but he was always anxious then.

“You have no idea,” he warned me. “You’ll go out for ten minutes to have a cigarette and come back to find a party going on and some drugged out queen dancing on a tabletop is squirting catsup on the wall and his drunk friends are cheering him on and there’s a mess to clean up before we open next day. You have to keep an eye out!”

He was right. Labor Day weekend was wild. We rarely closed before three am and the place felt like a disco. The music from the Ice Palace, directly across Bay View Walk, competed with the Nelly Deli’s own jukebox. I danced along with the customers; I never came out from behind the counter, just swung my dish towel overhead like a lasso in time to the beat. Things quieted down immediately after Labor Day, and I was happy I had taken the job. My schedule left most of my days free. I didn’t have to spend much money. I even saved.

Occasionally I felt lonely that last month and a half. Manny returned to the city mid-September to perform with Nikolais and teach dance at a new place called The Door. But Paul Thek and Steve Lawrence were still in Oakleyville and I visited often. Sam Green once gave me the use of his luxurious house for a few days. I sat in his bay window (it was literally a bay window) under Irish linen blankets he stored in a large wood chest, listened over and over to Peter Allen’s album Tenterfield Saddler, and made odd meals from his cupboard—e.g., a water chestnut and artichoke salad to go with one of the PB&J sandwiches I always took with me when I finished work on Mondays, using the bread that would otherwise go stale and Skippy Peanut Butter and Welch’s Grape Jelly I splurged on at Tiffany’s. And there was a makeshift society of houseboys, house-sitters, or seasonal workers in the hotels, bars and restaurants—a roving band who seemed to know each other and who moved from resort to resort all year long, following the sun on a gay circuit that included Provincetown, Fire Island and Key West. None of us owned or even had partial shares in the houses or rooms we stayed in, although the bartenders made the most money and talked about buying eventually. But the irony was that unlike the owners or renters who hurried to and from the city each weekend, we enjoyed the island for days at a time, not tied down to the demanding jobs that rewarded their holders with a salary that allowed resort rentals, happy instead to do menial, but essential jobs with such great benefits.

When I needed company, which wasn’t often, I could always find someone—there was the sweet, fey man with a pageboy haircut who walked the boardwalk in the Pines with a piece of needlepoint he never seemed to finish; or the compact, muscular little ex-Jesuit who invited me to enjoy the indoor-swimming pool in the house he was “watching” for the owners; the porn star who teased me in the basement corral the owner had built in his Cherry Grove house to act out his Western fantasies, or more interestingly, Morton Gottlieb, the Broadway producer, who struck up a conversation at the checkout line at Tiffany’s.

Gottlieb invited me to lunch at his house, on the western edge of town near the bay. To our surprise we had both grown up in the same neighborhood of Brooklyn, Prospect Heights. Our worlds overlapped physically and to a lesser extend culturally—he was Jewish and I was Irish-Catholic, and we’d gone to different schools—he to Erasmus Hall, I to Nazareth, a Catholic high school in East Flatbush. We marveled that the same landscape was the site of such contradictory milieux. We had no family or friends in common, but despite the thirty year difference in our ages—we traded stories and memories of various streets, houses and movie theaters—the settings of two Brooklyn boyhoods that though years apart, had many similar elements: games like Red Light/Green Light, Johnny On The Pump, Steal the Bacon, played blocks away from each other, he with his Jewish friends, I with Irish, Italian, and Polish Catholics. He told me to call his office and see his current hit, Sleuth, as his guest, but once back in the city I never followed through. I was both too shy to make the call, and also reluctant to accept a favor from someone who had clearly expressed a sexual interest I did not want to reciprocate.

By the first week of October, as the population thinned, the Nelly Deli only opened on weekends. I still had no desire to return to the city despite earning less money and the cooler autumn weather. Fire Island is a mile off shore—a thin sandbar no wider than a quarter-mile, with nothing buffering the ocean breezes. In late September and early October, walking on the beach during the day required the same sweatpants and hoodie I wore at night. My unheated room on the beach offered little protection against temperatures in the low fifties and even high forties.

Still, I hung on. I had never been alone this long and didn’t want to give up a solitude that meant more to me than the privilege of living in an expensive resort.

Finally, Jimmy told me that on Sunday, October 16th the Nelly Deli would serve its last customer and close for the season as soon as the final ferry departed that night. I could stay till morning, but I had to leave Fire Island.

It rained heavily the Monday morning I left. As the ferry crossed over to Sayville, I sat next to the window, reading D.H. Lawrence and looking up from the page now and then to watch the raindrops gradually replace the blurred image of Cherry Grove with a silvery network that reconfigured itself minute by minute.

I was relaxed and unworried. A phone call to Richie had let me know that I was no longer homeless. He and some new friends had moved into a four-bedroom apartment on 104th Street and Amsterdam Avenue. My solitude was at an end for the moment, but I could have what would otherwise be the living room.

I soon discovered I didn’t have to worry about money either. Once I’d settled in with Richie’s new friends, I called Manny. He also had good news. Claudette’s client base had increased. I could resume modeling for art classes. On 104th Street, we split the rent five ways, which came to $42/month for me. Posing naked, sometimes for nuns, I made more than that in a day.

October 31, 2013

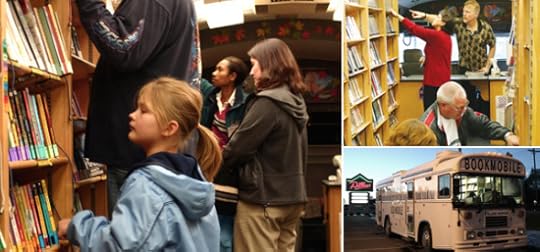

Out on the Job (And Safe from the Draft)–Library on Wheels 1971

I was in the front passenger seat of the library van next to Mario, the driver. My boss Mr. Buckley, the head librarian, hovered behind us, resting his elbows on our seat backs. The other two librarians, Jack and Maria were on the jump seats that flanked the front door, quietly reading. Mario was a good driver. Mr. Buckley had no problem keeping his balance even as we made a sharp turn off Ocean Parkway onto Surf Avenue, and Jack and Maria always told him they barely noticed we were moving. As we zipped past the Cyclone roller coaster Mr. Buckley asked me “What’s your lottery number, Steve?”

The question came out of nowhere. One minute we’re approaching Coney Island, my favorite stop of the week; the next I’m wondering how everyone will react to the announcement I know I will make somewhere in this conversation. I had promised myself that I’d never lie or deny that I was gay, but I didn’t just offer the information, nor did I go looking for opportunities to proclaim my sexual orientation. Besides, I made a point of revealing myself as clearly as I could to anyone willing to read the signs.

I looked up from my embroidery and caught Mr. Buckley’s eye in the rearview mirror. An enormous sunflower covered the left thigh of my blue jeans. The ring of outer petal-bearing florets overlapped and darkened where they curled at the edges. Inspired by some Chinese embroidery I’d seen, I took pains to make them as realistic as possible, using the satin stitch and the best thread I could buy. DMC had the richest colors and the widest range of shades. I used a bright daffodil yellow at the base of each petal and gradually worked in tans and light browns where the curled edges of the tips created shadows. But I made no effort to reproduce the intricate pattern of the inner disk flowers—I just filled in a large spiral with dark brown thread. I surrounded the sunflower with daisies, pansies and Black-eyed-Susan, set in a network of trailing vines studded with grapes and imaginary blue flowers. At least I’d never seen them anywhere but on my pants. One of the pleasures of riding on the library van was not wearing business clothes. All summer long I wore dungarees that I decorated relentlessly—going into every fabric store I passed to buy the cotton corduroy prints I sewed at night in a crazy-quilt pattern on the ass and down the back of the legs—inspired by the photo on the cover of Neil Young’s most recent album, After the Gold Rush.

“Ninety. My lottery number is ninety. But I’m not going anywhere,” I assured him. I didn’t say why, just wondered about his sudden interest in my draft status. He had to know it already—it had to be in my file somewhere, because I’d been asked on the job application. I’d filled it in, not sure what they’d make of it. I wondered if this had anything to do with my having seen him wandering up Christopher Street from the Morton Street Pier the day before. I’d greeted him casually, but we didn’t stop to talk, since he looked as if I was the last person he wanted to run into at that moment.

“Well how can you be so certain?”

Troop levels were decreasing in Viet Nam, but the draft had not ended. This was the second year of the lottery. I could still be called up as far as he knew. By the end of 1971 the army had called up numbers 1 to 125. I knew even in July that I wouldn’t be one of them, but didn’t want my draft classification casually discussed anymore than my being gay. I mean really—I thought I had sufficient minority statuses to deal with. In ascending order of malleability I laid claim to short, left-handed, red-headed, chubby and effeminate—each one had prompted teasing all through grammar and high school. Since high school I’d added “college dropout” and discovered that even “Catholic,” however lapsed, might provide an occasion for some subtle condescension from the odd new acquaintance. Queer and 4-F upped the ante; these were grown up, stigmatized minority statuses; they resulted in more than teasing: you could lose jobs, friends, and worse.

I could sense everyone waiting for my answer. The van had never felt so quiet.

Resting the threaded needle on my thigh, I ran my hands through my hair, combing it roughly so it hooked behind both ears and fell stiffly to my shoulders. By fall it would be long enough for a ponytail.

“Because I’m 4-F.”

This got Mario’s attention.

“4-F! How can you be 4-F? You’re a healthy young man.”

The moment I’d been hoping to postpone had arrived. As we pulled into a parking space in front of a nursing home, I announced: “Because I’m gay.”

Mario stared at me open-mouthed. Mr. Buckley drew in his breath. No one said anything for a few seconds. Mario shook his head and staring straight out the front window said “Whoever did this to you should be shot.”

There was already a line waiting for our arrival. In a few minutes, nurses and home health aides would be helping their charges select books. The van would be packed for the next two hours. The topic was dropped as soon as we opened the door. Jack and Maria led people to the subjects they were interested in. Within minutes we had a bottleneck at the front were there was a selection of new books and best sellers. But gradually, people spread out and browsed. Given the space constraints, it was a well-stocked, good-sized library with over 2,500 titles, on ten shelves, five on each side, organized in the standard Dewey decimal categories.

This was one of our busiest stops; I didn’t have to talk to anyone. I sat at the counter performing check-out duties, sliding a card with the return date in the book’s back pouch and replenishing my supply whenever necessary and the crowd thinned. At lunch hour I left the van as I always did when we were at Coney Island and walked back towards Astroland.

I planned to ride the Cyclone a few times and then gorge on one of Nathan’s hot dogs with everything on it. I loved the first bite when I cracked the crisp casing and the spicy beef juices blended with mustard, catsup, onions, relish and sauerkraut. The dreary bun, lightly grilled, was little better than Wonder Bread, but couldn’t diminish my pleasure. French Fries and a large lemonade completed my meal. The tension might be eased by the time I got back. If not, I hoped I’d be too rattled by the roller coaster and too sated to care.

I rode the Cyclone three times. I could only get a seat in the middle for the first ride, but snagged the last—and scariest because it shakes so much and feels like the car has jumped the track a bit—all to myself for the second. I ran to get the front seat for my last ride. Looking down the first hill and seeing the tracks appear to curve under is thrilling. I was nauseated but happy when I headed back towards Nathan’s.

I had two hot dogs as the rattling stopped and billions of neurons readjusted to the contours of my brainpan. Then I walked slowly back.

I knew no one had forgotten my comment and wasn’t surprised to find them discussing it when I stepped back onto the van. I saw Mario first. He just shook his head, turned and sat back down in the driver’s seat. Mr. Buckley said nothing. He stood listening to Jack and Maria’s debate.

Maria, with perfect Scandinavian liberal acceptance, was defending me to Jack.

“Steve is entitled to these feelings,” she told him. Jack liked Maria and was never the least bit argumentative, but replied, “Well, maybe.” Seeing me he smiled to indicate that whatever he’d just said, he would not behave any differently towards me. And now that I stood before them, the topic was dropped for the day. They cleared their lunch remains off the counter and we settled in for the ride to our afternoon stop. Maybe this would be just like family; the most important things never discussed unless forced upon us and then allowed to sink into our collective unconscious again, where we each worked them out as best we could. I hadn’t instigated this subject and dropped it as happily as everyone else. It would be interesting to see how things did or didn’t change in the next few months.

First the other clerks and librarians working back at the branch would find out; maybe I’d be brave and tell them if no one got to them first with the big news. Mario was capable of that. He said “Didja hear?” so often I thought of it as his unofficial middle name. And like a bad actor, he telegraphed oversized emotions to everyone in order to prompt questions about what was wrong—which he happily explained at great and tiring length. Mr. Buckley announced one day that we were leaving a few minutes late because we had to wait for Mario to calm down. He was busy “Nailing himself to the cross,” in irritation over some new regulation he didn’t agree with. But maybe I’d be lucky and he’d not want to even think about it. His powers of denial were, like my mother’s, industrial strength. Only a month ago, when every paper in town had a headline about the shooting of Mob boss Joseph Colombo during a rally of the Italian American Coalition, Mario insisted repeatedly “There is no such thing as the Mafia!” I had kept out of that one—I knew the Mafia existed. I knew that it wasn’t Chase Manhattan Bank collecting $200/wk interest on some my father’s $10- and even $20,000 gambling losses.

The big surprise for me was how little everyone else seemed to care. Mario had expressed some disgust but never mentioned it again; Jack seemed to think being gay was not as acceptable as Maria did, but he was unemphatic about it. And who knew what Mr. Buckley thought? Perhaps I simply caught him by surprise with my announcement and unintentionally put him on notice that I was a semi-dangerous character if he was, as I suspected, gay himself and not yet out or even consciously aware of his orientation.

Over the next thirty years, in job after job, my surprise has morphed into the expectation that all anyone really cared about was how well or badly I did the job, provided I didn’t force the issue. I didn’t evade it either—I was clearly out on all but one job in my entire adult working life—and I’m ashamed of that one instance. I know living and working in New York, the most liberal city in the country, contributed to this live and let live ethos. My delight grew as I realized this attitude wasn’t restricted to certain Manhattan and Brooklyn neighborhoods, like Greenwich Village or Brooklyn Heights, both having large, visible LGBT populations. Again and again, I discovered that so-called “ordinary” workers who lived in the outer boroughs, the land of Archie Bunker, really could care less about who I slept with—and readily accepted long-term relationships between same-sex partners whom they knew as co-workers. The rabid homophobe of my terrified youth rarely made an appearance in my day to day life, although they showed up frequently enough on television and at political rallies. It was a heartening discovery.

Still, tolerance, however mild and well-meaning, is not the same as acceptance, and much as I liked my co-workers, especially the African-American clerks who shared and helped deepen my taste for singers like Billie Holiday and Sara Vaughn, I was more and more certain I would have to find some other way to earn a living.

September 3, 2013

The Man Who Married Tiny Tim—Sexton to The Reverend William Glenesk, 1969

Some bosses are interesting. Sometimes that’s good. Until it’s not.

In late December of 1969, I saw a help-wanted ad for the position of sexton at Spencer Memorial Presbyterian Church in Brooklyn Heights. I knew nothing about Presbyterians. I don’t think I had ever met one before. I had even less idea what a sexton was, but I wanted to meet Spencer’s minister, the Reverend William Bell Glenesk, the man who had joined Tiny Tim and Miss Vicki in holy matrimony in a surprisingly somber ceremony on The Tonight Show. Along with thirty million others, I’d watched it. Despite lacking experience, knowledge or credentials of any kind, I applied. The ad had appeared in The Village Voice; how fussy were they going to be?

To be on the safe side, I did some homework. After a quick trip to the library and a perusal of the Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature I knew more than a little about the Reverend—all of it made the job even more appealing.

Years before his appearance on national television, journalists had been documenting Glenesk’s career in newspaper and magazine articles, beginning with a notice in The New York Times about his appointment to Spencer Memorial in 1955, while still a graduate student at Columbia University and Union Theological Seminary. From then on they regularly mentioned him, even listing, in an age when they were still considered newsworthy, the themes of his upcoming sermons. The Times had five articles about him in 1962 alone. In 1963 Look Magazine’s special issue devoted to “The New New York,” called Glenesk a “rebel in a Brooklyn pulpit.” In 1964 he threatened to defy a ban on Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, Fanny Hill and a Time Magazine profile noted that “the Rev. William Bell Glenesk incorporates everything from jazz bands to barefoot modern dancers in his freewheeling, experimental services.” His guests included Ruth St. Denis, Metropolitan Opera bass Jerome Hines, and composer Ned Rorem, who not only presented a concert of songs (Mourning Scene for voice and string quartet) with Adele Addison, he gave the sermon. All this was part of Glenesk’s vision of modern liturgy: “Any creative art is touched with the divine . . . you should not go to church out of habit. I’m all for the idea of enjoyment. You should go because it is exciting. One week you can come out walking on air; another time crawling on the ground.”

By 1966, he was indisputably famous, or infamous, depending upon which side of the generation gap you stood. That year he told a reporter from the Montreal Star, in descending order of unorthodoxy, that he was an agnostic: “Every honest Christian is an agnostic. There is a vital difference between I believe and I know.” He did not obey the Ten Commandments or advise others to. He called himself a pornographer and claimed “Every preacher of the Bible has to be part pornographer.” (See Girls Gone Wild in Old Jerusalem for confirmation of this.) Plus he had smoked pot, and, after a lawyer told him he’d be breaking the law by distributing the copies of Fanny Hill Putnam had provided him, contented himself with reading excerpts to his congregation.

He was so much more radical than the Nehru-jacketed, folk-mass loving “Father Get-With-It” priests I was in flight from, that he appealed to me. I had been kicked out of a Catholic boarding school three years earlier; now I was hoping to work for the opposition—a genuinely protesting Protestant. It all went straight up my rebellious teenage alley.