Out on the Job (And Safe from the Draft)–Library on Wheels 1971

I was in the front passenger seat of the library van next to Mario, the driver. My boss Mr. Buckley, the head librarian, hovered behind us, resting his elbows on our seat backs. The other two librarians, Jack and Maria were on the jump seats that flanked the front door, quietly reading. Mario was a good driver. Mr. Buckley had no problem keeping his balance even as we made a sharp turn off Ocean Parkway onto Surf Avenue, and Jack and Maria always told him they barely noticed we were moving. As we zipped past the Cyclone roller coaster Mr. Buckley asked me “What’s your lottery number, Steve?”

The question came out of nowhere. One minute we’re approaching Coney Island, my favorite stop of the week; the next I’m wondering how everyone will react to the announcement I know I will make somewhere in this conversation. I had promised myself that I’d never lie or deny that I was gay, but I didn’t just offer the information, nor did I go looking for opportunities to proclaim my sexual orientation. Besides, I made a point of revealing myself as clearly as I could to anyone willing to read the signs.

I looked up from my embroidery and caught Mr. Buckley’s eye in the rearview mirror. An enormous sunflower covered the left thigh of my blue jeans. The ring of outer petal-bearing florets overlapped and darkened where they curled at the edges. Inspired by some Chinese embroidery I’d seen, I took pains to make them as realistic as possible, using the satin stitch and the best thread I could buy. DMC had the richest colors and the widest range of shades. I used a bright daffodil yellow at the base of each petal and gradually worked in tans and light browns where the curled edges of the tips created shadows. But I made no effort to reproduce the intricate pattern of the inner disk flowers—I just filled in a large spiral with dark brown thread. I surrounded the sunflower with daisies, pansies and Black-eyed-Susan, set in a network of trailing vines studded with grapes and imaginary blue flowers. At least I’d never seen them anywhere but on my pants. One of the pleasures of riding on the library van was not wearing business clothes. All summer long I wore dungarees that I decorated relentlessly—going into every fabric store I passed to buy the cotton corduroy prints I sewed at night in a crazy-quilt pattern on the ass and down the back of the legs—inspired by the photo on the cover of Neil Young’s most recent album, After the Gold Rush.

“Ninety. My lottery number is ninety. But I’m not going anywhere,” I assured him. I didn’t say why, just wondered about his sudden interest in my draft status. He had to know it already—it had to be in my file somewhere, because I’d been asked on the job application. I’d filled it in, not sure what they’d make of it. I wondered if this had anything to do with my having seen him wandering up Christopher Street from the Morton Street Pier the day before. I’d greeted him casually, but we didn’t stop to talk, since he looked as if I was the last person he wanted to run into at that moment.

“Well how can you be so certain?”

Troop levels were decreasing in Viet Nam, but the draft had not ended. This was the second year of the lottery. I could still be called up as far as he knew. By the end of 1971 the army had called up numbers 1 to 125. I knew even in July that I wouldn’t be one of them, but didn’t want my draft classification casually discussed anymore than my being gay. I mean really—I thought I had sufficient minority statuses to deal with. In ascending order of malleability I laid claim to short, left-handed, red-headed, chubby and effeminate—each one had prompted teasing all through grammar and high school. Since high school I’d added “college dropout” and discovered that even “Catholic,” however lapsed, might provide an occasion for some subtle condescension from the odd new acquaintance. Queer and 4-F upped the ante; these were grown up, stigmatized minority statuses; they resulted in more than teasing: you could lose jobs, friends, and worse.

I could sense everyone waiting for my answer. The van had never felt so quiet.

Resting the threaded needle on my thigh, I ran my hands through my hair, combing it roughly so it hooked behind both ears and fell stiffly to my shoulders. By fall it would be long enough for a ponytail.

“Because I’m 4-F.”

This got Mario’s attention.

“4-F! How can you be 4-F? You’re a healthy young man.”

The moment I’d been hoping to postpone had arrived. As we pulled into a parking space in front of a nursing home, I announced: “Because I’m gay.”

Mario stared at me open-mouthed. Mr. Buckley drew in his breath. No one said anything for a few seconds. Mario shook his head and staring straight out the front window said “Whoever did this to you should be shot.”

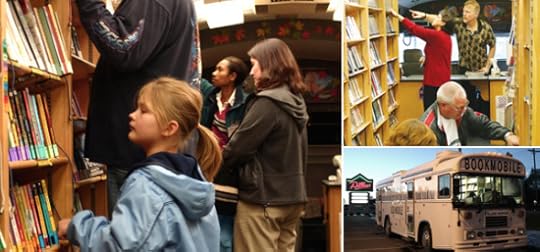

There was already a line waiting for our arrival. In a few minutes, nurses and home health aides would be helping their charges select books. The van would be packed for the next two hours. The topic was dropped as soon as we opened the door. Jack and Maria led people to the subjects they were interested in. Within minutes we had a bottleneck at the front were there was a selection of new books and best sellers. But gradually, people spread out and browsed. Given the space constraints, it was a well-stocked, good-sized library with over 2,500 titles, on ten shelves, five on each side, organized in the standard Dewey decimal categories.

This was one of our busiest stops; I didn’t have to talk to anyone. I sat at the counter performing check-out duties, sliding a card with the return date in the book’s back pouch and replenishing my supply whenever necessary and the crowd thinned. At lunch hour I left the van as I always did when we were at Coney Island and walked back towards Astroland.

I planned to ride the Cyclone a few times and then gorge on one of Nathan’s hot dogs with everything on it. I loved the first bite when I cracked the crisp casing and the spicy beef juices blended with mustard, catsup, onions, relish and sauerkraut. The dreary bun, lightly grilled, was little better than Wonder Bread, but couldn’t diminish my pleasure. French Fries and a large lemonade completed my meal. The tension might be eased by the time I got back. If not, I hoped I’d be too rattled by the roller coaster and too sated to care.

I rode the Cyclone three times. I could only get a seat in the middle for the first ride, but snagged the last—and scariest because it shakes so much and feels like the car has jumped the track a bit—all to myself for the second. I ran to get the front seat for my last ride. Looking down the first hill and seeing the tracks appear to curve under is thrilling. I was nauseated but happy when I headed back towards Nathan’s.

I had two hot dogs as the rattling stopped and billions of neurons readjusted to the contours of my brainpan. Then I walked slowly back.

I knew no one had forgotten my comment and wasn’t surprised to find them discussing it when I stepped back onto the van. I saw Mario first. He just shook his head, turned and sat back down in the driver’s seat. Mr. Buckley said nothing. He stood listening to Jack and Maria’s debate.

Maria, with perfect Scandinavian liberal acceptance, was defending me to Jack.

“Steve is entitled to these feelings,” she told him. Jack liked Maria and was never the least bit argumentative, but replied, “Well, maybe.” Seeing me he smiled to indicate that whatever he’d just said, he would not behave any differently towards me. And now that I stood before them, the topic was dropped for the day. They cleared their lunch remains off the counter and we settled in for the ride to our afternoon stop. Maybe this would be just like family; the most important things never discussed unless forced upon us and then allowed to sink into our collective unconscious again, where we each worked them out as best we could. I hadn’t instigated this subject and dropped it as happily as everyone else. It would be interesting to see how things did or didn’t change in the next few months.

First the other clerks and librarians working back at the branch would find out; maybe I’d be brave and tell them if no one got to them first with the big news. Mario was capable of that. He said “Didja hear?” so often I thought of it as his unofficial middle name. And like a bad actor, he telegraphed oversized emotions to everyone in order to prompt questions about what was wrong—which he happily explained at great and tiring length. Mr. Buckley announced one day that we were leaving a few minutes late because we had to wait for Mario to calm down. He was busy “Nailing himself to the cross,” in irritation over some new regulation he didn’t agree with. But maybe I’d be lucky and he’d not want to even think about it. His powers of denial were, like my mother’s, industrial strength. Only a month ago, when every paper in town had a headline about the shooting of Mob boss Joseph Colombo during a rally of the Italian American Coalition, Mario insisted repeatedly “There is no such thing as the Mafia!” I had kept out of that one—I knew the Mafia existed. I knew that it wasn’t Chase Manhattan Bank collecting $200/wk interest on some my father’s $10- and even $20,000 gambling losses.

The big surprise for me was how little everyone else seemed to care. Mario had expressed some disgust but never mentioned it again; Jack seemed to think being gay was not as acceptable as Maria did, but he was unemphatic about it. And who knew what Mr. Buckley thought? Perhaps I simply caught him by surprise with my announcement and unintentionally put him on notice that I was a semi-dangerous character if he was, as I suspected, gay himself and not yet out or even consciously aware of his orientation.

Over the next thirty years, in job after job, my surprise has morphed into the expectation that all anyone really cared about was how well or badly I did the job, provided I didn’t force the issue. I didn’t evade it either—I was clearly out on all but one job in my entire adult working life—and I’m ashamed of that one instance. I know living and working in New York, the most liberal city in the country, contributed to this live and let live ethos. My delight grew as I realized this attitude wasn’t restricted to certain Manhattan and Brooklyn neighborhoods, like Greenwich Village or Brooklyn Heights, both having large, visible LGBT populations. Again and again, I discovered that so-called “ordinary” workers who lived in the outer boroughs, the land of Archie Bunker, really could care less about who I slept with—and readily accepted long-term relationships between same-sex partners whom they knew as co-workers. The rabid homophobe of my terrified youth rarely made an appearance in my day to day life, although they showed up frequently enough on television and at political rallies. It was a heartening discovery.

Still, tolerance, however mild and well-meaning, is not the same as acceptance, and much as I liked my co-workers, especially the African-American clerks who shared and helped deepen my taste for singers like Billie Holiday and Sara Vaughn, I was more and more certain I would have to find some other way to earn a living.