Jonathan Price's Blog

February 3, 2025

Icons--The Book

In this book, Jonathan Reeve Price explores computer icons as cultural artifacts, elegant images, and bundles of code.

He describes how these icons were originally created as part of a graphic user interface in the early days at Apple. He then reflects on how these little drawings have evolved and become ubiquitous in our culture.

The images themselves, enlarged in these pages, are vivid graphic forms. Their functionality, name, and overtones speak to Price, and he lets us overhear his poetic response to each of 100 icons.

About the authorAuthor of 30 books, conceptual artist and concrete poet, Jonathan Reeve Price shows digital art and visual poems in galleries, museums, and anthologies.

He created the first style guide for Apple's writers and designers, developed their first online help systems, and wrote documentation for AppleWorks, FileMaker, and the Mac.

In this light-hearted study, he explores the complex powers of these tiny interactive elements that we use every day.

Why computer icons?Computer icons carry culture, history, and code.

As buttons, they awaken functions deep inside the system. As images, they evoke old technology, memes, and mysteries. As artwork bearing their own titles, they come loaded with implications, overtones, and attitude.In this book, you’ll enjoy getting a new perspective on such familiar but alien objects.

Kirkus ReviewsJonathan Reeve Price examines the deeper meanings underlying computer icons in this unconventional poetry collection.

Combining technical insight and artistic expression, the poet focuses on 100 icons (of the available 3,000) from Google’s Material Design set, asking questions such as, “Is the image beautiful? Does the shape invite me to tap? Does the picture telegraph what the icon can do for me?”

He considers how several of the icons that we use daily are relics of the past, from an attachment’s paper clip (“reminder / Of paper pages”) to an email’s letter shape (“The stamp—how quaint!”).

The transition from tactile to virtual and the related grief over the loss of a physical world are recurring themes in the collection.

• “Brush” considers the “ancient tool” that “says take me in your hand, / Feel the soft bristles, dip them, and paint.”

• Of the heart icon that users use to “favorite” online posts, he writes, “How many meanings this sign enacts. / It performs as noun, verb, and glyph.” (“Favorite”).

• The bell, that incessant “attention parasite” that notifies users of activity, reminds the author of “the brass dinner bell that called / My grandfather in from loading hay.” (“Bell”).

• “Reply_all” earns the label of “The most dangerous icon of all,” provoking shame that “sends you racing back, / As you replay that one unthinking click.”

Price ends on “Ampersand,” praising that “Elegant emblem / Ornate placeholder / Connective pointer.”

These poems are short yet thought-provoking, inviting readers to slow down and consider the meanings of the icons they mindlessly tap all day long.

Though the topic might seem at odds with poetry, Price blends the two seamlessly, as in “360,” based on the rounded arrow that allows users to rotate views on a map: “Imagination cannot show me such a tour. / This icon launches code, / Spins the Earth around its axis, / Turns a city street into a whirl, / And races like an angel around a volcano.”

Booklife in Publishers' Weekly, August 12, 2024Interrogating the everyday digital images like shopping carts and the triangle-within-a-circle button that you click to make media play, this collection of visual poems from Price (author of The Liquid Border) offers a humanist decoding of the symbols that govern our contemporary digital world.

In a series of 100 poems, Price extrapolates from the functional images that we may take for granted—the icons for “format paragraph,” “restore from trash,” and more from Google’s Material Design set—what significance, resonance, and vibrations that he can, while exploring what it means to click on them and allow “a more powerful intelligence” than ours to “act on our behalf.”

The poet describes, in an introduction, his history at Apple creating the first style guide for virtual icons, works that he now sees as “small poems, austere artworks.”

Sharp insights abound in Price’s crisp, plain-spoken verse (on the shopping cart icon: “Is this the archetype of America, the bin // We can never fill?”), and Price’s emotional range is broad enough to encompass satire, despair, and flashes of real feeling, especially in lines on icons whose designs harken back to the world before: paper clips, paint brushes, the three-columned facade of a bank. “Nothing says bank like a Greek temple // Holding your money, blocking // You from whatever is left”, Price writes.

The poet’s voice is knowledgeable and often funny, exposing the strangeness and power of such easy-to-overlook images (like the “Angular and sharp” Bluetooth “rune”) with wry asides and deeply human expressions of longing for greater connection.

Production grades

Cover: A-

Design and typography: A

Illustrations: A

Editing: A

Marketing copy: A

Icons is a collection of poetic works in the technology, philosophy, and cultural writing genres. Penned by author Jonathan Reeve Price, this interesting book presents a multidisciplinary exploration of computer icons, combining essays, imagery, and poetry. Price delves into the cultural, historical, and functional significance of one hundred different icons, revealing their deeper meanings and symbolic power.

He blends personal reflection with cultural analysis, showing how these everyday digital symbols evoke ancient technology, memes, and mysteries, and how they serve as functional buttons within our systems. The book elevates the mundane icons we encounter daily into a form of symbolic art, encouraging readers to reconsider the rich implications behind these seemingly simple images.

Author Jonathan Reeve Price takes an unusual and highly original viewpoint to deliver a captivating journey through the often-overlooked world of computer icons. The book's exploration revealed that these small symbols are so much more than we give them credit for, becoming indicators of culture, history, and the modern codes we live by. As simple and effective artworks, each with its own title, the icons come loaded with implications and attitudes that Price deftly unpacks in wonderful lyricism and bright, enthusiastic, exploratory text.

His background as a conceptual artist and concrete poet shines through, blending technical expertise with poetic imagination. This fusion makes each page a revelation, transforming everyday icons into rich symbols of human experience and cultural evolution. A few of my personal favorites included the hark-back to classical art in ‘Palette’, the meta-exploration of capturing imagery itself in ‘Lens Blur’, and the highly amusing, energetic feel of ‘Gesture’. Overall, Icons is a must-read for anyone interested in poetry and the cultural impact of technology on our world, and I enjoyed it immensely.

--K.C. Finn, Reviewed on 06/02/2024

Icons is not your typical poetry collection. It lives up to its title and promise by delivering observations on computer icons that reflect not just programmer code, but the powers of practicality. An icon condenses lines of potentially confusing code into a tappable one-hit-solves-all image, that acts (to the author’s mind) as ‘a small poem.”

The author doesn’t begin with his poetry. He sets the stage with reflections on his background, the evolution and importance of icons, and details about visual and philosophical connections that marry computer worlds and human lives.

The icons that Price surveys don’t just lie in computers, but in the greater world at large. Here they are condensed into singular descriptions, as in the poem ‘360’:

This icon launches code,

Spins the Earth around its axis,

Turns a city street into a whirl,

And races like an angel around a volcano.

The unexpected marriage of computer-generated processes (such as the code ‘border_none,’ designed to avoid putting a box around content) and broader life perspective (as in ‘Download,’ defined as “the process of bringing content and code from the cloud”) creates a synthesis of poetic, social, and IT wonder that will especially attract programmers and those unused to an art form reflecting and connecting engineering and life.

Budding philosophers, too, will find in reflective pieces such as ‘Insights’ a fine sense of revelation and connection inviting discussion and contemplation:

When you look within, is this

What realization brings? Has wisdom

Hit so hard that you see stars?

Enlightenment comes cheap when an icon

Promises to turn numbers into second sight.

Libraries seeking poetry collections will find Icons an attractive enhancement of not just contemporary poetry collections, but suitable for top recommendation to non-art and engineer types who will be happily surprised at how relevant their insights and experiences are for the rest of us.

--Diane Donovan, Senior Reviewer, Midwest Book Review

Technical CommunicationThinking about how to evaluate communication through graphics can be of interest to those of us in the technical communication community as we can use and evaluate such means of communication in our own work. Jonathan Reeve Price explains in Icons: Poems how the elements of the computer icons we use today and when these graphical elements were created. They were part of what Apple used in their early graphical user interfaces. Price reflects on how these icons today have become part of our culture and everyday digital life. The author takes each of 100 icons and has authored a poem about each one. We typically do not stop to think so deeply about icons. So, it is fun to see Price’s poetic take on each icon. He has a striking enlargement of each icon—one per page—with his poetic musing where he thinks about such things as name and function. Price’s musings can be funny, insightful, and thoughtful. The icons discussed in Icons: Poems are 100 of the 3,000 icons available from Google’s Material Design set. An example is (p. 26), which has a poem in Icons: Poems, that points out in part how versatile the icon is as it can be a noun, verb, glyph, and much more. In looking at each icon, Price asks questions such as whether the icon is beautiful. He also evaluates how effective the icon is in explaining what the shape is meant to express and even questions how humans connect with each other. In our own work, we can ask ourselves related questions about the graphical devices we are using. Such questions and musings can be fun and useful. Anyone involved in communicating information graphically could benefit from reading Icons: Poems to gain insight into how to use, develop, and evaluate a graphical element. The poetry in this book lets us think more deeply about how human beings want to and can communicate and connect. The poetry made me think of the expression—a picture is worth a thousand words—as I thought about how an image or icon can express more than a verbal description alone. Icons: Poems also made me think about the icons in a church and how through these icons, humans try to “persuade that spiritual being to act on our behalf” (p. 15). I asked myself if the people who picked the word “icon” to depict elements in a graphical user interface were right in picking that word. I suppose it was not a bad choice as I could not produce anything better. It was especially notable to me that Price is an STC Fellow with a fabulously interesting background. “He quit the art world to join Apple Computer in 1982, where the introduction of MacPaint was a life-changing event for him. He created a style guide used for many years by technical communicators—How to Write an Apple Manual, later published in several editions under the title, How to Communicate Technical Information,” as explained at the https://www.jonathanreeveprice. com/ site which also notes how Price “has taught information architecture, technical writing, content development, and databases at New York University, Rutgers, New Mexico Tech, and as an adjunct professor, through the University of New Mexico, as well as online through the University of California, Santa Cruz.” Wow! Wow! Wow!--Jeanette Evans, January 31, 2025 Jeanette Evans is an Associate Fellow of the Society for Technical Communication; active in the Ohio STC community, currently serving on the newsletter committee; and co-author of an Intercom column on emerging technologies in education. She holds a master’s in technical communication management from Mercer University and an undergraduate degree in education. FormatsPaperbound Edition 126 pagesPublication: March 15, 2024ISBN-10: 0-9719954-8-6ISBN-13: 978-0-9719954-8-2Dimensions: 8 x 8 inchesPrice: $9.95Amazon page: https://amzn.to/3Vgk9ojHardcover Edition126 pagesISBN-13 : 979-8990368293Item Weight : 8.6 ouncesDimensions : 6 x 0.48 x 9 inchesAmazon Page : https://amzn.to/44Yd6Uu

Kindle Edition:File size : 4426 KBASIN : B0CY95QNH2Simultaneous device usage : UnlimitedText-to-Speech : EnabledScreen Reader : SupportedEnhanced typesetting : EnabledX-Ray : Not EnabledWord Wise : Not EnabledSticky notes : On Kindle Scribehttps://amzn.to/3VhSEtB

PublisherThe Communication Circle4704 Mi Cordelia Dr NWAlbuquerque, NM 87120

(505) 259-7937

Contact: JonathanReevePrice at Gmail

August 30, 2024

Video Art--The Beginnings

Historically, American video art begins in the late Sixties within and around the studios made available at educational stations in Boston, San Francisco, and New York, thanks to charitable grants from the Rockefeller Foundation, the John D. Rockefeller II Fund, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the New York State Council on the Arts.

Numerous artists came to WGBH (Boston), KQED (San Francisco), and WNET (New York) to explore the gear. What drew them there?

Many entered the new medium primarily because they disliked the limits of some earlier one. With Nam June Paik, for instance, we find a man who mastered all the forms of music available to him and found them all boring. He destroyed the piano, the violin, the opera; what was left? Only when he found an instrument like the TV set could he fulfill himself without merely attacking his artistic fathers.

What general notions of art did people enter video with? The first idea, the first item in their cultural luggage, was the cult of personality. That romantic Western idea that art should somehow be self-expression still held sway, although most contemporary artists are high enough to empty their work of obvious emotionalism. Still, the self became the subject for such wildly different video artists as Vito Acconci, snarling and biting; Nancy Holt, teasing, cherishing, remembering her aunt; Hermine Freed, reenacting, questioning her own baby photos; Lynda Benglis, arousing her own sex. And diary tapes seemed to be almost a phase through which most people go, turning on the camera and letting it run wherever they traveled, like Shigeko Kubota’s Europe on Half Inch a Day and Juan Downey’s very personal tour of Latin America. These tapes reveal exactly how much the person dares to reveal, or cares to; the audience can test the maker’s character, as performer, and as camera aimer. “Art should be original because I am,” runs this theory, at its crudest. Still, we are entitled to ask of each work of video art: How real is this person?

A second notion stemmed from the very multiplicity of media available to any artist. Rich inheritors of the modern capitalist world, many creators took for granted that we could make color film with sound, photographs that could be printed on any surface from plastic to canvas, prints that could run the gamut from Gutenberg to rubber stamp, painting that could jump from Pop to Minimal to eye-popping Op, sculpture that could stand still or jerk around the room, theater that might run out of the theater to create temporary events in the street, music that might include random sounds as part of the score, and network television showing old-fashioned drama alternating with kiddie games plus forties-style movies. Given so many tools, the beginner often felt overwhelmed, but eventually he or she became reconciled to the fact that year by year one had to learn new skills.

An artist moves through a number of media, acquiring each, domesticating each, growing into and outgrowing each. The unity is in the person. This experience leads to a conception that Douglas Davis describes as pursuing one idea through many media. He pounds his hands on the inside of the TV set, then on an inkpad, then on paper. Throughout the sequence the audience can imagine his act. So some artists, like Keith Sonnier, see themselves as the central figure in their work, and they move from one medium to the next, learning it, leaving a record, going on to the next field. Others see their own action as the basic image, to be shown in video, but also in print, or photograph, or map, or text as well. And even those who explore other media do so in order to bring back some technique that will enliven their video, as Bill Etra does when he studies computers. Video is one among many; therefore, it is only a medium. You and your idea pass through many media in a lifetime.

Conscious of the enormous range of media available, many artists have evolved a third general notion: that they should explore the uniqueness of each medium. Each medium does certain things well, other things poorly, the argument runs. The task of the artist is to study the new medium, to find out what it does well, and then to explore those areas fully. Is this something that only video can do? Buoyed by the way in which Sixties artists challenged painting (what is painting?), Nam June Paik toyed around with the actual wiring of his television sets; Richard Serra and Vito Acconci tried communicating within closed-circuit systems; Douglas Davis tested out video cameras, hanging them out of skyscraper windows, burying them in Germany. Reducing TV to mere light levels, flowing electrons, blur, and continuous change, artists have gradually narrowed down the areas that seem uniquely video. It is here that the best art takes place. Not imitation film, but genuine video, not theatrical photographs, but live video. In early video art, the American ideal, it seems, has been to create an intensely personal style as one explores the unique capabilities of video, consciously comparing it with media such as painting, words, or music.

True to their era in another way, video artists also placed a high value on ambiguity and activity. That which is difficult to perceive seems to fascinate us, as we try to bring it into focus. And video is a natural for a people who feel that the act of perception itself involves the act of thought. Rudolf Arnheim, author of Art and Visual Perception, says that certain cognitive operations normally called thinking occur during, not after, perception—simplifying, analyzing, abstracting, synthesizing, correcting, comparing, resolving, recombining, separating, establishing context. The uncertain video screen provokes all these operations, keeping mind and eye occupied continuously, until we decipher “how it is done.” At that moment interest drops off. So sheer activity becomes important. An active artwork is one that changes your perspective on the scene rapidly, showing you new ways of understanding the event, new angles of perception. Instantly replayed, quickly dialed, video changes so fast that it can be made as active as the mind creating the work.

In making an artwork perceptually ambiguous and psychologically active, what choices does an artist have, what tendencies in the medium can he or she exploit? Artists have evolved a rough list of choices that they feel they must make when entering video, decisions thrust on them by the medium, opportunities dictated by our culture and by the nature of the machinery. If we explore these choices, we can see some of the questions confronting each artist as he or she begins to work and each viewer as he or she watches for the first time. In addition, we may arrive at a rough fix on the simmering critical debates alive in video art during the early Seventies.

1. Are the Changes in the Image Primarily Electronic, or Are They Mechanical?When an image changes electronically, we watch a gradual transformation from within, as if the form on screen were growing by itself. But in mechanical changes we flip from one picture to another as in a slide show, each break a complete cut.

Electronically we seem to be following a constant, flowing metamorphosis, as when pools of color seem to belly up, then contract and rearrange themselves. With mechanical change, we have what Shigeko Kubota calls “Stripe, stripe, stripe; cut, cut, cut”—the physical chopping of the videotape into segments, providing strong contrasts, fast jolts.

2. Are the Images Basically Natural, or are They Predominantly Machine-Made?Natural images are humans, plants, animals, landscapes, seen clearly enough to be recognizable; we are discussing the basic image, before any tinkering gets added. Most conventional TV dwells on such imagery, until it comes to commercials, and most video artists go through a video diary period, showing real, if fuzzy, scenes.

Machine-made images are artificial when they start (geometric shapes, computer graphics, highway loops, machinery itself) or gradually turn natural images into abstract ones.

3. Is the Screen Overloaded with Data or Underwhelmed with a Minimum of Audiovisual Information?Few artists inhabit a middle ground. A few tapes provide an absolute minimum of information—Bruce Nauman walking in circles for fifty-six minutes, Nam June Paik showing moonscapes unchanging for hours.

Other tapes tend toward overload; active, even frenetic, they combine many different kinds of images, techniques, colors, speeds, creating a dense thicket of information, like Juan Downey’s multiple reflections on the mirror in a painting by Velásquez.

4. To Edit? Or Not to Edit?Or, really, does the work stress the editing possible with tape, or does it ignore that potential, stressing instead the unbroken accuracy, the actualness of the time?

The unedited tapes come when an artist sets up a camera in an environment to record whatever goes on or when someone like Minimal artist Bruce Nauman deliberately repeats an action, recording it exactly as long as the action takes, such unedited tape may be exhausting to watch, but it gives the effect of reproducing real time accurately.

Edited tape emphasizes the editing itself, as when Hermine Freed intrudes in Art Herstory to comment on her own “unedited” comments, made earlier, during the actual taping.

5. Are We in the Present, with the Video Camera Running Right Now and Each Image Instantaneous, or Are We Supposed to be Aware of Different Time Strata Embedded Within One Tape, Completed in Time Past?The question of time itself becomes a vital one for many artists. Real time means the camera is on right now, and you are seeing what is really going on; the view is actual, contemporaneous, live. Acconci is in the basement right now, threatening you with a pipe; those people on the screen waving are right behind you.

Other time is usually past, but it may suggest a science-fiction future, too; such tapes tend to emphasize multiple times, mostly all past, through editing, through layering, through actual dialogue.

Occasionally an artist like Lynda Benglis in her Now will record complicated real-time interaction with the machine, to give you the feeling of being there right as she does it, yet the very fact of its being just a tape demonstrates that we are actually in the past.

6. How Many People Are Affecting the Image? How Many Get Input?Multiple input would mean that many people can get into the act, as in Allan Kaprow’s Hello, where people all over Boston say hello to each other, Bill Etra’s Astral Projection, in which many musicians end up in the stars, Bruce Nauman’s corridor installation in which the audiences’ backs show up on the screen, Nam June Paik’s synthesizer demonstration, in which your image appears under his manipulation, Douglas Davis’ phone-in marathon called Talk Out.

By contrast, many tapes are made solo, with the communication all one way, from the artist to you, with no chance for feedback, comment, or interplay.

7. How Much Interplay Is There with the Environment?During these early days, the bulk of video art remained on tape, but many artists like Davis and Kaprow tried to reach out of the set into the wider environment. Some did this physically, arranging TV sets in a pyramid in a museum, then showing you different glimpses of life in- or outdoors, stacked up together. Juan Downey put cameras in rows, got people meditating on their own, and showed the pictures to audiences, establishing a temple atmosphere; Nam June Paik distributed sets with ocean images on the floor of the Galeria Bonino, calling it Video Sea; Shigeko Kubota’s Nude Descending a Staircase encased the TV sets in the staircase and showed pictures of a nude descending that staircase.

By contrast, purely tape pieces seem content to remain in the box; they assume the framing device of the TV screen and ignore the immediate surroundings, not including them, not affecting them.

8. Is the Focus on Process or Product?A final decision confronting the artist is whether to hide the labor, displaying only a final product, as in Downey’s mirror of a painting, or to reveal exactly what went on during the making, stressing the process.

Some works suggest that the process is more important than any final version: Nam June Paik’s synthesizer (you step into its range, and you become its subject, yet the machine continues without you when you go), Sonnier’s Animation (he has not edited; we have a half hour of raw outtake from his experimentation, not a polished cartoon, and when an engineer asks, “Do you want to save any of this stuff?” Sonnier saves and shows it all, the whole process).

The artists who lean more toward product hide how their tapes were made, pretending that the art was born fullblown from the forehead of the artist, drawing attention away from the making of video to some other subject.

ChoicesEach choice an artist makes inevitably affects the next, and on any given question the sophisticated artist may tend to mix both techniques within one work, consciously combining opposing extremes.

Artworks that show just one tendency or another may seem pure, but boring. Boringness is not bad, but it tends to generate rage in audiences, no matter how hip.

An active artwork is one in which our view changes fairly rapidly. And the most interesting work often shows us ordinary reality as it undergoes the transformation into a purely machine-made view of the scene.

Several of the best composite half hour tapes alternate sparse segments with overflowing detail, moments open to a general public with soliloquies.

Once we understand the two horns, then, we may enjoy watching the artist dancing back and forth across the dilemmas.

Such considerations also suggest artistic divide in our culture between two general tendencies. As in much contemporary painting, we see a division between stringent “realness” and playful artifice, between hard, if full, information and lush entertainment, between an almost didactic urge to point to mere process and a more old-fashioned aesthetic impulse to create a lasting work.

In video, then, one tendency tips toward realistic pictures of real people, without too much extra information or editing, right at the moment, with as many people as may walk into camera range showing their effect on the immediate environment as an essential part of the piece—stressing that process rather than any afterproduct.

The other tendency tilts toward more artful image, larded with data, carefully edited, hinting at many more periods than just the present, controlled usually by one determined artist working with tape to make a striking final product.

Any given artist must pick and choose elements on both sides of that cultural divide, and the results always depend on personal taste. But in most artists’ careers, there is a movement away from the simple and realistic toward the more artful.

In each of these areas, personal style is decisive. Personal style, to me, is the trace left by intense personal conflict, as Paik’s reaction against traditional music shows up in his fondness for random electrons, and Etra’s feeling that he is eternally a student learning to control the equipment results in the brevity and clarity of his études. Ask all the questions you want of an artist’s work, and you will eventually come up close to the person. Perhaps the growth of an artist is a proper subject for study. Biography is a legitimate part of criticism, and even essential, for it suggests the conflicts that lead up to an individual’s making certain stylistic choices, yea or nay.

When we go beyond particular tapes or installations to size up entire careers, we are weighing a life. Some people—through art—seem striking. Their image startles, amazes, impresses, attracts. Their picture burns in our mind’s eye, ambiguous enough to puzzle, but active enough to keep our attention. Among artists, they are the video pioneers.

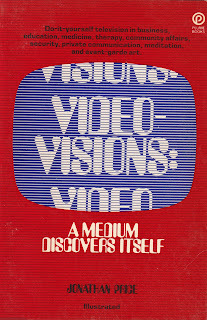

From Jonathan Price, Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself. New American Library. 1977.

About JonathanReviewed in Videography, November, 1977; New York Times by Jeff Greenfield, December 18, 1977; Performing Arts Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 1978), by John Howell; Leonardo, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Summer, 1980), by W.H.M Kaiser.

LinkTree: https://linktr.ee/jonathanreeveprice

MuseumZero site: www.museumzero.art

Twitter: http://twitter.com/JonathanRPrice

Instagram:

Pinterest:

Facebook:

Linked In:

Amazon Author Page:

Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/41600924.Jonathan_Price

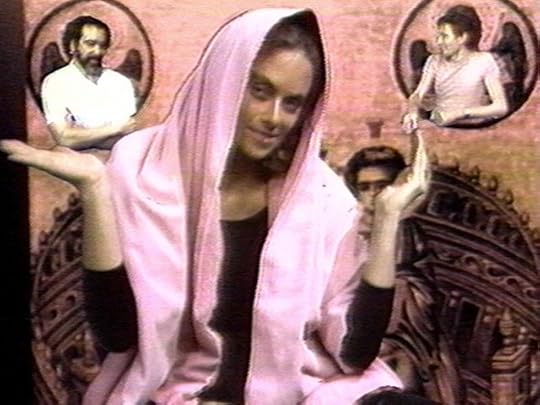

Video Pioneer Lynda Benglis

Lynda Benglis, Now, 1973

Lynda Benglis, Now, 1973Lynda Benglis was making large polyurethane foam sculptures when she discovered video in 1970.

Lynda Benglis, Night Sherbet A, 1968 Her floor pieces look like liquid captured in the midst of pouring. These mounds are garish in color—sometimes even the gray looks grotesque.

Lynda Benglis, Night Sherbet A, 1968 Her floor pieces look like liquid captured in the midst of pouring. These mounds are garish in color—sometimes even the gray looks grotesque. Benglis began to move away from tangible objects, expressive things, to video’s unreal world, where the color is even wilder, the scale is never sure for long, and the forms change even faster than her plastic foam.

She seems to have been struck by the fact that you can build up layers of tape, just as she had piled up different colored swirls of plastic.

In an early tape, Noise, we see two layers of title—one on the videotape on the monitor, one on the screen itself—wobbling back and forth. In the miniature screen surrounded by black we see a man talking. He gets up. We see his waistline, then the woman he is talking to. The camera watches the monitor, causing the screen to bounce slightly in the middle, but assuring us that we are watching a tape of a tape.

Oops—an extra frame appears around the man’s neck. We are now seeing a third-generation tape.

The man, Robert Morris, drinks looking straight into the camera, and other faces, more inarticulate, talk to the camera, making slight noise.

Robert Pincus-Witten claims that this recycling of tape shows a fondness for the Minimalist painters who first stressed rigid checkerboard patterns and grids. But serial imagery is typical of all work done since the late Fifties: Pop art soup cans, Op art patterns, or black paintings. The willingness to repeat herself, to overlay so much detail that you cannot understand very much, also comes from her McCluhanesque understanding of media overload. She piles on so much data that you would think some message would come through, but in fact this tape is singularly uninformative. She shows the husk of data, without a kernel.

Benglis began to play, too, with the contrast between audio and visual. In Discrepancy the picture does a slow zoom through leaves toward a tree, then back to a window which reflects the scene quite steadily, while the radio raps about ’70 Oldsmobiles, boogieing, street gangs, rebuilt cars, Alexis Lichine wines, and a garden of love. Somewhere between the picture and the sound the discrepancy lies. Words in her work go one way, picture another, and we are left in the middle wondering.

This doubt becomes intense in Mumble, which is deliberately muffled and foggy, in both picture and sound. We are told insignificant data, but so seriously that we see she is imitating the form of commun-ication; by emptying out content, she stresses the form itself, in this case, video. Her voice says, “This is a tape I made of Morris in my studio sometime in December.” We see a face in front of a TV screen which is displaying breakup. After repeating that, she comes back in. Robert Morris drinks wine, his back to us. We are told that Robin Toriano, weaving upstairs, is making that kachunk noise in the background.

Morris says, “I think I want to talk about work.”

Someone off screen says, “Work is voluntary.”

Lynda explains that Morris didn’t say that, that the figure on the left didn’t say it, a voice offstage said it. After more explanation they frankly say, “Mumble mumble.” Lynda Benglis intrudes to say, “The phone really is ringing next door.”

Mainly we are watching a face talking in the foreground left, while behind him a TV screen shows another man staring away from us, sipping wine. The foreground man mumbles, and Lynda Benglis breaks in to explain whatever he has said, commenting, “This is an interesting dialogue. Relationships are very important.”

Thoughtless language sent from two heads, one seen, one not. “I don’t think I ever went to an analyst.” This is true; little is revealed, despite the up-front documentation of “the facts,” provided by our ever-attentive guide.

“The figure in the middle who you can’t see now is not there at all.” The man’s words are no longer in sync with his lips.

Voices struggle through several layers of mechanical interference, rarely reaching articulation of more than a word or two, except from Lynda Benglis who is allowed full sentences. “The phone is ringing,” she says flatly, not going to answer it. “The phone is really ringing.”

The man on the inner screen withdraws; that set goes to snow, then bars; then this set snaps back to snow. The only sound is the tape deck revolving. Benglis has made silence precious.

To make the layers even thicker, even more complicated, Benglis allowed Robert Morris to fiddle with her tape some more, in an aptly titled Exchange.

“To comment on,” the videotaped picture of a TV screen says at the start of Morris’ piece, and his voice runs on defining “comment,” paralleling, giving examples of, reverberating this dictionary list in an echo chamber. Meanwhile, the picture remains resolutely blank. Now a face in the foreground says, “This is a tape of her tape of his tape.” His tape made the basis for Lynda Benglis’ Mumbles, which is a muttered dialogue between her foreground voice, a man’s head, and his tape of himself drinking wine. How complicated, how frustrating to anyone who wants to know just where he is. This tape has seven previous exchanges on it. She has edited out herself talking about her work; she put other voices into the foreground; he wiped her face, leaving only her voice. As he goes on talking about the changes they have made, invoking Uccello, while he lights a cigar in front of a TV, he mutters, “Most of this was suppressed or distorted for the purposes of art.” The original, like the skeleton of a plastic sculpture or the cartoon for a large painting, has disappeared.

And Morris goes on rewriting the text, commenting on its awkwardness. We see a series of slides of a crowd. “It’s really sentimental,” he says in front of a monitor showing himself. “The telephone is ringing, and I’m backing out of the frame—it’s this absence thing.”

He says experts accused him of rehearsing. He reads more text off a sheet pasted below the tube; then the picture is a freeze-frame slide of himself, while the voice goes on, saying that Lynda Benglis had suggested a dialogue; decisions were made and reversed.

She had said, “By now I know who I want to sleep with, but lending my equipment is something else.” He says hostility emerged. And at no point does she appear on the screen. The exchange is therefore minimal, as he implies. He goes on talking of absence, separation, me and her, communication losing clarity, untranslatable Italian, gestural language, and he begins to wonder if his maniacal pursuit of art has not always led him to cause harm to women. Lynda’s voice returns, “The telephone is ringing.” He says, “It’s a horse with three balls—work, thought, process—self—and thought, work, process—the other.” Very little is said about the makers, and therefore little is said about non-communication. The singsong lulling monologue is as deliberately boring as Samuel Beckett, but with far less control than Beckett’s Film; this is endless because they have so much tape. There is her face, and she smiles. “Feelings of love and anger are absorbed by the blotter of art.”

The coldness is belied by the sensitivity of his voice, which changes from what he himself calls “narrative tone” to an art-lecture style, to jokes, to recalled maxims—“I never assume any continuity.”

He is fluid, flexible, intelligently avoiding any verbal progress; he produces no plot—a paralyzed narrative. The pictures are used like slides: a photo of two racing cars, a video of him not moving. He ends rereading several sentences five or six times, interspersing a description of Sterling Moss’s wreck. “They found him hanging on an acacia bush.” A voice in the background says, “How boring the visual image is.” The two cars stand there still on the screen. Later, he says, he urged everyone to mumble. He would stand in his loft for days, and one day she found him, and said, “Your hands are like ice.” He says, “I’d love to freeze the frame here and be done with it.” Done.

Pincus-Witten points out that Morris and Benglis “fed each other’s consciousness about the potential of video,” and as they trade tapes and play multiple editors, the results get “awfully tangled. At its simplest—yet most artistically complex—let’s say that Morris is both grist and image for Benglis as she is for him.”

Having stayed off screen, Benglis finally decided that she had studied her voice enough; now her body should appear. In Now she makes love to her own face; her tongue imitates a penis or an erect clitoris; her own lips receive that delicate phallus, thanks to the magic of two cameras and tape. She asks herself, “Do you wish to direct me?” And we again slip down the rabbit hole to a world in which we are never clear what comes first or second. She kisses and then says, “Let’s see how it is.” Both faces go off to look at this tape, then return.

“OK—now. OK—now. OK—now.” At each word the woman on the left, now alone, does a new trick with her tongue. “Start recording. No. Start recording. No. Start recording.” This time, in a red smear, the two play with “now,” bouncing it back and forth. The extreme limitation on language makes this performance dramatic—clearly planned—but Lynda Benglis includes the rehearsal, as well as the perfected version.

With video there is no “perfect take” as there is in commercials for capitalist TV. “We are recording,” they both say, many times, as if this tape were built up in multiple layers, while the faces bleat and moo across a red-and-green gulf, made up of their own images reproduced hugely and out of focus behind them, on a screen which is patted by two hands just behind the women in the foreground. “Let’s run that through and see how it is,” they say, and end it.

From such activities, encouraged by Robert Morris’ own bravura machismo (he appeared in a leather-and-chain outfit on a poster advertising his April 1974 show), Benglis has moved to the Female Sensibility, in which she seems to masturbate with a languorous friend, teasingly close to a lesbian liaison, yet so unclear it still remains a striptease.

And in November 1974 Benglis purchased a full-page ad in Artforum, the snobbiest review going, posing nude with a huge dildo. She had become male and female, offending both avant-garde and bourgeois at one show. The ambiguity of that image, so shocking and so clear, so perfect for media reproduction, yet so calculated to be impossible for family magazines to reprint in a Christian culture, that rumored photo told about in words, the Marilyn Monroe calendar of the art world, became her pièce de résistance.

Benglis, then, has moved from feminine forms—liquid, layered, tissuelike—to video that at first brought us only her voice, offering information that told us nothing, facts that were not true, data that did not help, then on to video in which she appears twice over, loving herself more and more, rising to climax with a friend, then finally stripping away the fuzz, the smirch of video, posing for a very sharp Kodak-style photo so undressed she seemed exposed, yet astride a gray-blue-pink fake cock, her hobbyhorse, her very theatrical prop.

Through video she has learned how to use her own body as an art material, how to make layers of meaning in an apparently simple shot, how to leave an audience in the middle of a dilemma, wondering which way the answer really lies. Is she male or female? Is she this face or that? These are artful fictions she creates, and they draw our minds after her, trailing behind her image like a picture on tape delay.

From Jonathan Price, Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself. New American Library. 1977.

About JonathanReviewed in Videography, November, 1977; New York Times by Jeff Greenfield, December 18, 1977; Performing Arts Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 1978), by John Howell; Leonardo, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Summer, 1980), by W.H.M Kaiser.

LinkTree: https://linktr.ee/jonathanreeveprice

MuseumZero site: www.museumzero.art

Twitter: http://twitter.com/JonathanRPrice

Instagram:

Pinterest:

Facebook:

Linked In:

Amazon Author Page:

Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/41600924.Jonathan_Price

Hermine Freed Gets Into Video

Interview by Jonathan Reeve Price in the book, Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself, New American Library, 1977.

“I’m a New Yorker,” says Hermine Freed, one of the most chic of the gallery video makers. “Now if a bum stops me, I’ll give him a quarter and have a little chat.” In fact, she got into video by talking.

“It all started when I was doing a TV program on Channel Thirty-one,” she says as we chat in her high-rise steel-and-glass apartment. “I was the art critic in a book review program, and after doing several of these programs, I was getting very frustrated with the TV medium and how unable they were to manipulate it. I was told to propose a program of my own on art, for Thirty-one, and just at that point, the station lost its budget, and people were being fired all over the place. But I was still writing my proposal. And when I finally went to the station master, he said, ‘I don’t want to read anything else, it’s been a bad year, I want to see it.’ And I thought, super eight and no sound, how am I going to do that? And I remembered some friends who were doing video, and I called them, and they came by.

I was in East Hampton at the time, so the natural thing to do was what was in the neighborhood, so I did Jim Rosenquist, Alfonso Osorio, who lived next door to me. And I was hooked, once I had touched that video camera and saw what it could do.”

What struck her right off was the difference between carrying a portable video camera into somebody’s house and walking in with an entire conventional TV crew. “I could never do on TV what I did on video. I could never walk through somebody’s property very unself-consciously, without them being aware of the camera. I could never just let them be what they were, paint their pictures, do their things.”

She went to Roy Lichtenstein and settled in. “I was using video for one reason, because it was—unlike film—a medium that could capture reality. The anecdote for this is Lichtenstein.

I spent a few days, he was painting, I was there, he doesn’t care, and then after we were finished, he said, ‘You know, Barbara Rose came by with a film crew the other day, and they had me pose in front of the canvas with a dry brush. You didn’t do that.’

So I said, ‘Naw, I sure didn’t.’ So that was one of the first things that excited me about the medium. But of course, the more you use any medium, the more you become aware of the fact that this truth is not true either.”

Looking back at one of those early tapes, Lichtenstein’s Still Life (1972), I find it organized, edited, and arranged like an essay. The shape is verbal. “Your early pictures were cartoons,” Freed says, and Lichtenstein replies, “I was interested in inexpensive reproductions.”

He talks of dots, halftone colors, and Freed, sitting at the other end of a wicker sofa, asks about “Portrait of Madame Cézanne,” and Lichtenstein’s diagrammatic painting appears. That was his first imitation of another artist, and it was quickly followed by his fake Picassos—Lichtenstein hopes his become genuinely simpleminded. He rearranges his hair.

“Do you look for your images, or do you find them?” she asks. Both, he implies. We see talking heads, then the two figures on the sofa, an informal interview exactly like regular TV, down to the insets of still lifes.

Finally, we switch to him filling in a broad area of canvas as he goes on talking, saying, “I don’t particularly want it to look subtle.”

Red, yellow, blue, and black are his main colors, but this tape is in black and white; he has forgone his trademark dots for crosshatching, arguing for simple shticks. He has a white bowl outlined—sparks of white will show through.

He wants forms that are easy to reproduce, and these show up well on the tube. Where the first half of this tape imitated conventional TV as closely as Lichtenstein aped comic strips, this section in the studio imitates old film visits with the artist.

I enjoy watching his hand running smoothly down the canvas as he talks of mechanically producing the textured area next to his freehand stroke. “I just alternated pieces of tape.” At this point, Lichtenstein knows more about painting than Freed does about video: this tape ends by being a comment, not art in itself.

Still, there was the feeling of casual immediacy. “Of course, this business of immediacy. I love the medium because of my own temperament. You can use it the way you use paint. I love the fact that I can record it, play it back, see what it looks like, do it over again, change it, without having to send it out to be processed, wait two weeks. I usually find that when I have something I’m thinking about, I have to deal with it now; if I let it go two weeks, the immediacy of my feelings goes.”

From immediacy she moved toward artistic questioning of the video truth. “At that point there were artists using video, but not many. We’re now around 1971–2, it’s only three years ago, now that I think about it [summer 1974], but it seems like a million years, because at that point there was no video being shown anywhere.

Bruce Nauman had made some tapes. I don’t think I was aware of what he had done. Anyway, for a thousand and one reasons I wanted to just make tapes. The more I was making tapes, the more I wanted to make tapes and use them to make art. They seemed to solve a lot of extra-aesthetic problems, as well as some aesthetic ones. So the first tapes I made were tapes that seemed to deal with that medium in an art context.

“The very very first tape was called I Don’t Know What You Mean, and it was a collage of images that were ambiguous as far as quote reality is concerned; it was really a tape about illusion versus reality and the ability of the video camera to see things that the eye doesn’t see or to make images that have an existence of their own.

And all of the tapes, in that sense, have dealt with the line between subjective and objective experience. The one thing that I found the video camera doing that excited me the most was that it objectified the self. If I were recording this conversation on video and then were to play it back, I would see myself removed from the feelings that I have right now. So I would see me as you see me rather than the way I see me.”

Objective one moment (seeing yourself as others see you), subjective the next (going on camera again, to make some more tape), you can be in and out of your body five times a minute. In Two Faces she has one side of her face look at the other side. “The resulting image was me looking at myself. The activity of the tape is me reacting to myself physically, turning, shaking my head, rubbing noses with myself, and kissing myself.” This narcissism, like that of Louise Etra, Lynda Benglis, and Joan Jonas, seems inspired by the unique privacy and publicity of video. But it also stems from the speed of video.

“The electronics of video! Just the fact, you saw my Two Faces thing, you could not with film have that, oneself responding to oneself, kissing themselves, with one side of the face, and then the other side of the face, responding to oneself in that kind of way, the way you can supervise real time on video. It’s that ability to take contemporaneous time—two things happening at the same time.”

We see her name, hear clicks, then see half her face staring at us, reproduced three times to our right; she turns around; the mirrors are reduced to two, then one; she revolves again as hums come into the sound track.

Now, slowly, she leans into the center of the screen, trades heads, rises back up, as her mound of hair separates. We have front on one side, back on the other—faster and faster—shaking her hair. The feeling reminds me of two frames of a kaleidoscope fitting together; arms up, she smiles, leans into the mirror, and gives her image an Eskimo kiss, nose to nose. Then tongue tips.

She wiggles, trying to figure out how to manage a real kiss, succeeds, bends the other way, smiles equally, pats herself, and nibbles like a fish, shares tongues, regards her target with seriousness, returns to the gray, squeezing her nose, caressing hair; her double becomes a ghost, her black being the mimic’s white.

The translucent figure intrudes into her own head, puzzling her; then she absorbs the ghost and stares at us head-on, tucking away a strand of eerie hair. This is video play; she grins and is gone. Huzzah, a Narcissa immersed in her mandala-like pool, mirroring her own doubleness, recovering unity with a twist of the knob.

Reflecting on her newly chosen medium, Freed began to discern two reasons why artists and critics were so dubious about video. One was the false association with conventional TV and its commercial tawdriness. Second was the inevitable tie-in with kinetic art, the high-technology fun-and-games style that had more to do with machines on vacation than art. “It is ironic that artists have been concerned with movement since The Nude Descending the Staircase, but as soon as art really does move, it becomes another form entirely. We cannot look at a videotape in the same way that we would look at a painting or a sculpture.”

Casting about for some frame of reference, she found Abstract Expressionism. “Just as minimalism eschews the personal, video and abstract expressionism are rooted in it. Just as minimalism denies the importance of process, abstract expressionism and video rely on it. Just as minimalism avoids psychological incidents, abstract expressionism and video embrace them. Just as space is concrete in minimalist sculpture, it is elusive in both abstract expressionism and video.” She justifies a comparison with painting since video occurs within a still frame, a flat surface. And she stresses the “objectification of self” as typical of video, the psychological feedback, the real-time response to self, mentioning Peter Campus, Bruce Nauman, Richard Serra, Lynda Benglis. They all “question the possibility of arriving at objective perception."

"Nancy Holt’s tapes allude to the impossibility of isolating experience that is also found in a great deal of abstract expressionist painting. In most abstract expressionist paintings, form and gesture extend beyond the framing edge of the canvas, suggesting boundlessness. . . . when the total image is revealed at the end of Holt’s tapes, it is still a mere fragment of a larger view from which it was taken.”

Most striking for her was the emphasis on process. “Rarely is a videotape totally scripted and rehearsed before it is taped. One quality of the medium which differentiates it from film is the greater possibility of spontaneity. Often in the process of recording a videotape, ideas suggest themselves which had not been a part of the original plan. Video is organic; it can be replayed immediately, and reworked. It is possible to erase or tape over unwanted segments and to redo edits until they work. In this sense, it is closer to the process of painting an abstract expressionist work.”

In Art Herstory, Freed recapitulates art history using paintings of women. She inserts herself into each, as the model.

Sometimes the sound is live, from the recording session; sometimes it is a voice-over, expressing an afterthought that raises questions of time and process.

“The sequence of images on this tape is different from that in which they were made.” She is dressed in a shawl. We hear an open mike: “Stand by to cover up. OK, it’s time to disappear. I can’t see either one of you. Give me your hand, Brucie.” A small figure lifts an arm. She reflects: “Might I have altered history to squeeze in an image . . . to fit my needs?” Bruce Kurtz complains, “But I feel like a midget next to you.” She replies, still looking angelic, “You damn well better be.” Next we see her in the middle of a cutout; she lifts her foot. “I’m trying so hard to fly.” Someone hands her a video camera. Meanwhile, the voice-over asks, “Is one of these women more real or more an idealization for me?” Now she sits with a shawl in a nineteenth-century pose, fiddling with video cable, instead of thread. “Some of the women that I’m portraying I wouldn’t want to be. But this is one I wouldn’t mind being.” (Madame Récamier.) She adds, “Even a portrait is theater.” How self-conscious, how bitchy, how true. Then we have Odalisque, the nude women in the Turkish bath. She is nude, back to us, against the painting blown up. She calls out to the unmoving painted figures, as if they were her cast, “OK, girls, hold those poses.” She pats a body, and the voice-over says, “I can identify more clearly with the events of the past now. Time is catching up.”

She does Renoir, Van Gogh (she ad-libs, “Zee chickens, they have not been fed, zis book, she is not very interesting”), Gauguin (“Can’t you ever help with the kids around the house—paint, paint—my neck hurts, Paul”), Duchamp (“Much time has gone by since the first day”), Miro (“I was surprised to find all the icons, a rosary, a priest”), finally Warhol’s Marilyn (“I like the way I look”).

Her features shoot through time, erased, cosmeticized, dressed up, undressed, sometimes close to the original, sometimes wildly far. She is deliberately anachronistic—poking the video camera around the seraglio. She shifts our reality every few seconds: one moment in the scene, one in the studio making the picture, one afterward thinking about it all. Time dissolves under her humorous assault, and the tape itself becomes the only present.

In Family Album, Freed explores her own photographs, commenting, “Childhood seems like a sad time to me.” She shows the pictures to friends from age five, and they laugh together. “I remember wondering if my own child would be like me,” she adds, showing a picture of her pregnant, then of herself as a child. “I remember thinking that grown-ups were right.” Then, through video tricks, she shows the grown-up people right where they were in the photographs from childhood, and they all talk about it. “Can I change the future by remembering the past?”

Freed is full of questions. She tells us what she was feeling when the pictures were taken (“Betty, why are you so mean to me?”), then flashes forward to the present (“I don’t remember babyhood much anymore. I don’t remember when Daddy and I started fighting”).

Best moment: She is smiling at another girl at a prom. Now she can say what she felt: “Hope you spill the punch all over your pretty dress.” This is a real reel reexamination, expressing what was smoothed over before, in life and in portraits.

The courage to use her own life, the questioning attitude, the boldness of her honest anger, the humor are very much hers. Direct, yet perplexing, engaging, witty, and sensual, the style of this piece answers her last question: “What is me anyway?

--Jonathan Reeve Price

Excerpt from Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself, New American Library, 1977

For more:

Freed, Hermine, "Video and Abstract Expressionism", Arts Magazine, Vol. 49, No. 4, December 1974

Freed, Hermine. “In Time, Of Time.” Arts Magazine (June 1975): 82-84.

Freed, Hermine. "Where do we come from? Where are we? Where are we going?". In Ira Schneider & Beryl Korot. Video Art: An Anthology (1st ed.). New York:Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. 1976 ISBN 9780151936328.

Freed, Hermine, "Correspondence," in Vasulka archive, http://www.vasulka.org/archive/Artists2/Freed/

Videos available at https://www.vdb.org/artists/hermine-freed

About Hermine Freed:

Braff, Phyllis "Blending Media and Memory In Punchy, Original Ways", The New York Times, (June 14, 1998).

"Hermine Freed", Landmarks. 2017-08-16.

"Hermine Freed | Video Data Bank".

About Jonathan

LinkTree: https://linktr.ee/jonathanreeveprice

MuseumZero site: www.museumzero.art

Twitter: http://twitter.com/JonathanRPrice

Instagram:

Pinterest:

Facebook:

Linked In:

Amazon Author Page:

Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/41600924.Jonathan_Price

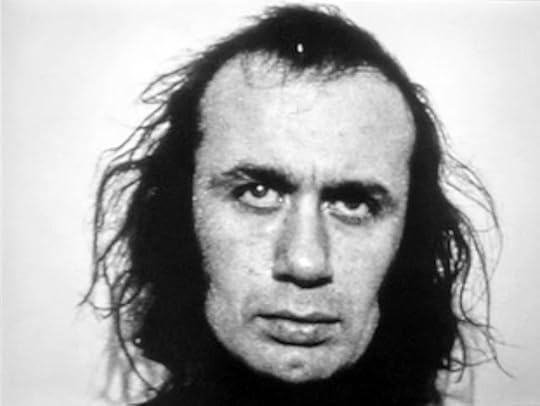

Video Pioneer Vito Acconci--Early Video

From Jonathan Price, Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself.

New American Library. 1977Vito Acconci makes himself his best subject. His sadomasochist acting out horrifies and absorbs audiences: psychologically revealing, such material risks much more than Nauman’s walking or self-painting. Acconci puts himself under claustrophobic pressure and records the shocking or disgusting results.

Acconci began as a prose writer and moved to poetry, which he saw as a way of filling space. The page was a performance area. His poems were spatial.

Then he began using his body as subject and object. He went to Max’s Kansas City, a restaurant featuring events by artists, and rubbed his left forearm for one hour, producing a sore. The body was a blank piece of paper, and he began madly drawing on it. “My body can be a place on which an event is enacted.”

Acconci started by using Super 8 film. In See Through, he is, as he described it, “Facing a mirror, punching at the mirror, punching at my image in the mirror until the mirror breaks and my image disappears.” In Blindfolded Catching (1970), he is “standing blindfolded while rubber balls, one at a time, are repeatedly thrown at me. Alarm reaction: auxiliary mechanisms are mobilized.” In Hand and Mouth (1970) he was “Pushing my hand into my mouth until I choke and am forced to release my hand; continuing the action for the duration of the film.” In Openings he pulled out the hairs around his navel, explaining that he was clearing the film frame and opening himself up. Clearly Acconci likes to make his audience wince. In his first video, at the Museum of Conceptual Art in San Francisco, he focused a camera on the back of his neck, then watched the monitor, as he took a match, and burned off a tuft of hair at the nape of his neck.

Already he was aware of the medium.

“I need an action that can coincide with the feedback capacity—I have to find something to redo—I can sit in front of the monitor, stay concentrated on myself, have eyes in the back of my head, dwell on myself, see myself in the round” (1970).Video works better than film to point at his own image. In Centers (1971), he waggled his finger at his own face on the monitor, while a camera there turned the activity around. “I end up widening my focus onto passing viewers. I’m looking straight out by looking straight in." He filled his mouth with saliva, making his face a balloon until he couldn’t hold any more. The saliva burst through his lips. He collected the spit in his hands and the picture on videotape.

Acconci extended the paranoid, the terrifying, the painful in a game of blind man’s bluff called Focal Points (1971).

“My position is constant: I’m blindfolded, I stand facing the wall. The camera drifts, moves to focus on different objects in the room, wherever the cameraman wishes—at irregular intervals, the camera focuses on my neck.

The camera functions as a stare—my attempt, throughout, is to intuit when I am being stared at, what side the stare is coming from.”His attacks expanded to include another person--Kathy Dillon. In Prying the camera focuses on Kathy’s eyes. “Her goal is to keep her eyes shut—my goal is to force them open.”

Here the quality of the performer’s life—his idea of fun—comes into question. He gives hints but does not seek an explanation of his interest in prying open her eyelids:

“I might be trying to win a point, to make her see what I’m getting at—she might be trying to stay inside herself, refusing to come over to me—I might get under her skin, insinuate myself with her—she might be fighting herself, suppressing her curiosity, her desire to look things over.”In Sound Barrier Acconci has Jay Jaroslav scream. Acconci tried to force the man’s mouth shut.

In Claim (1971) he defends a basement.

“I’m in the basement, blindfolded, seated on a chair, at the foot of the stairs—I have at hand two metal pipes and a crowbar—I am talking aloud, continuously, to myself—talking myself into a possession obsession. . . . I’m alone down here . . . I’m alone here in the basement . . . I want to stay alone here . . . I don’t want anyone with me . . . I don’t want anyone to come down here with me . . . I’ll stop anyone from coming down the stairs . . . I’m alone here in the basement . . . I’m staying alone.”The video here acted as a warning; a visitor could see and hear Acconci murmuring, threatening, down the stairs.

“If, during the first hour, I had hit someone, I would have stopped, shocked, horrified; if, during the third hour, I had hit someone, I would have used that as a marker, a proof of success, a signal to keep hitting.”Such a hostile attitude toward an audience suggests the impact his videotapes have.

In Remote Control he sets up two rooms with a box in each. Kathy Dillon sits in one, he in the other; they can see each other only by monitors. She has a rope, and he tells her how to tie herself up in it. “My aim is to convince, control myself—in so doing, I can convince, control Kathy,” he says, telling her, as she follows his directions. “You’re resisting a little, tightening . . . but I’m drawing the rope softly along your skin . . . you want me to do it, want me to continue.” He continues hypnotically, “She stops the action, she’s not convinced, I have to coax her back—she ties herself, I know she’s only acting, she doesn’t feel it, I have to lull her into it—she should do the action only when she feels impelled to; she might resist later, she doesn’t think of resisting now.”

Net: These are power-mad ploys, using video mainly as documentation and sinister tool, caring more about himself and his “control” over his audience than about the medium or its possibilities.

From Jonathan Price, Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself. New American Library. 1977.

About JonathanReviewed in Videography, November, 1977; New York Times by Jeff Greenfield, December 18, 1977; Performing Arts Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 1978), by John Howell; Leonardo, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Summer, 1980), by W.H.M Kaiser.

LinkTree: https://linktr.ee/jonathanreeveprice

MuseumZero site: www.museumzero.art

Twitter: http://twitter.com/JonathanRPrice

Instagram:

Pinterest:

Facebook:

Linked In:

Amazon Author Page:

Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/41600924.Jonathan_Price

Video Pioneers--Nancy Holt, Serra, Smithson

Nancy Holt, Boomerang, 1974

Nancy Holt, Boomerang, 1974Excerpt from Jonathan Price, Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself.

New American Library. 1977

Nancy Holt and Richard Serra borrowed some of Leo Castelli’s video equipment and made Boomerang.

“Yes, I can, I can hear, I can hear my echo,” Nancy Holt says, listening to her headphones, as the sound track drags out each word.

As she says, the words don’t seem to have the same forcefulness as when she speaks in ordinary life; her brain feels slowed down.

“I am filling up a vocal void; I find I have trouble,” she reflects like an upper-class patient recording her sensations for a doctor. Her face is imprinted with the Channel 7 logo, and as her sound retreats, she says, “Something else is coming in on me.” The logo disappears. She says, “Words become like things; they boomerang back. They bounce back. Again, I hear an empty space.”

She looks off screen, answers an unrecorded question, “Sure,” and is replaced by a printed phrase: “AUDIO TROUBLE.” This holds long enough to make me think of going to the bathroom; then she comes back, nodding, asking, “Am I on?”

She discriminates between immediate time and delayed time, which is like a mirror. She cannot see herself in a monitor; her eyes stare onto the floor. The echoes and tape delays come back in on her, surrounding her with her own mind, sounding like a goddess in the old movies.

“Light in its immateriality is like the sound in its immateriality.” She has performed a thorough and therefore radical verbal and musical analysis, even though Richard Serra has kept the visual image very conventional TV—an unmoving headshot, interrupted by blue space, and occasional logos.

How much more intelligent this is than Serra’s own solo tapes. In his Surprise Attack, for instance, someone tosses a metal block back and forth from hand to hand while someone else, his voice unpunctuated by the effects of this movement, reads a long prose paragraph about self-defense, ending with many seesawings back and forth on the theme of thinking. The tosser waits for each new sentence to begin and loses its rhythmic parallel as the philosophic language goes Germanic, talking of successive cycles of “He thinks we think,” concluding that the hypothetical robber who has spent the last two minutes debating like a bourgeois idealist over whether to attack or not decides to do so: “He must.” QED.

And in TV Delivers People, another Serra solo, we see a lot of words giving a liberal socialist view of the network stranglehold over media.

“The product of television, commercial TV, is the audience,” reads the tape roll, sliding up to a cheery Muzak score.

“You are the product of TV.” The sentences rise to the ceiling as the sentimentally gay music hops along, defied by the words: “Corporate control advocates materialistic propaganda—propaganda for profit.”

What he says is true and deserves the capitalized repetition he gives it. He says, “TV programming dominates the exposure of ideas and information. . . . There is a mass media compulsion to support the status quo.”

The blue background and the floating white letters, though, make this piece a bulletin, a verbal broadside minus any pictorial variation or original music. As video, then, it is minimal—glorified words. This primer on the economics of corporate TV is video since it represents one man’s anger, his personal theses tacked to the screen, and copyright in 1973, as if network TV would ever want to rip him off for such a truthful tape. So Serra tells the truth, but in these tapes he has gone far enough beyond conventional film and TV.

Nancy Holt, by contrast, uses words to ask questions, not to make pious statements. She presents challenges and puzzles. She stresses the fuzz, posing us riddles. If she made the same pictures with film, we could see right off what that is. “I’m holding a twelve-inch tube up to the monitor. Can you tell me what you see?” A wall moves up form the bottom, jutted into by a doorframe, or what Jerry Clapsaddle calls “a vertical recess.” An architecture buff, he reports on what he perceives: “Gee, I don’t see anything in that.” The next one he sees: “I see a rectangle coming in from the top, a recess, I think that’s a rainspout.” He spots a fixture, a window, two horizontal recesses (“I think they’re axial—one on top of the other”). A jeep in the foreground puzzles him, since he interprets the black tire as a hole in the building.

Holt shows us parts of a scene and encourages us to try to perceive the whole. She shows that seeing is imagining. “I’m going to expose the first circular image,” she says at the start of Zeroing In. We see a wobbly X. Ted Castle says, “It looks like a crossroads or an airstrip.” We see four more extra dark holes, ghost circles. I see someone on a bike riding around. “It looks like an insect,” he says.

Nancy Holt says, “Very vaguely.”

Closing that hole, she exposes another: “That’s very murky.”

I see the traffic going past. I deduce we are on top of a high building, staring at the view in small pieces.

The middle circle shows traffic moving up the screen past a building. “It could be automobiles.” Could be? Obviously is.

“Yeah, I think so. It’s a little out of focus.”

They analyze it in terms of gray and white, as if it were only a graphic image. He says, “It’s very realistic.”

“What else do we see? There are some very ill-defined dark things.”

We go to another circle. Medium gray geometric shapes provoke this comment: “This looks exactly like a building—I mean, there’s nothing you can do.” Ted lamely suggests ships, an imaginative jump that hints they are trying to show how we project meaning onto light images.

They analyze the supposed windows, the so-called smoke, and move to parked cars, careful not to call them by their name too soon, plus “that huge black thing” as if we were air photo intelligence agents, counting army trucks and missile silos.

She exposes all five circles. “Is there a pattern forming here?”

“The lower left seems very isolated; it doesn’t seem part of this scene at all.” The X is graphically different—a stark contrast, where the others provide fuzzy textural gradations. But why doesn’t the traffic go up into the upper left? It does; a building intervenes.

She points with a pencil to the connections between all five parts—and the insect on the white X. The dialogue smells like a teacher educating a student on the ways we perceive. To figure the scene out, a human would have pressed up against the hole to see it all. Clearly video alone shows so little that you need most of the scene, plus much talk, to grok it all.

We zoom in for a close-up of the center, and they talk through each detail of the intersection—manhole cover, streetlamps, tree limbs, windows, pedestrians, buses, nearness, focus, the insect quality, who’s going to turn, patterns of people, exhaust fumes, continuity of sidewalk, unusual events, possible parking lots, the sex of the walkers, blur, soft focus, architectural guesses, white areas, possible signs, a very Bauhaus building, traffic flow, differing distances, changing light, ways of telling exactly where this is, in the real world, a composite picture. Finally, we get a look at the whole scene, to blessed silence. One sees in two seconds “What it is,” and only the memory of their words proves how superficial each instant recognition is. One categorizes—oh, that’s a big building, and a street, and a playground area—and one looks away. One ignores the details so painstakingly mulled over here; a small circle returns, then goes to black.

“Now during this part of the tape,” Nancy Holt begins Going Around in Circles, as we see a small circle open up in the screen; we see a small man in it. More circles open, five in all. People are wandering around from one circle to the next. A man comments that he was looking at the monitor while they did it, as the camera shot through the cardboard cutouts. Everyone has a sheet of paper in his hand explaining how to move—but chance enters, too. Bruce Kurtz, who had been on the ground, said the diagram seemed ordered, “but what I was doing was disordered.”

“In all systems something like that happens,” Nancy Holt says. They are all commenting afterward. She points out that the cardboard card with peepholes is one physical element, the ground is another—with the rocks placed to show where one would be visible. Both are like stage sets.

She asks the members of her group for evidence. What did it feel like to be taped? One man was most involved in the process—the slippery grass, the slope, the running. The people clump in the center circle, as we hear these afterthoughts discussed, and the camera closes in on the group. Most people claim they felt more attuned to the diagram—and the window. Bruce Kurtz reveals that Nancy had been talking to them on a walkie-talkie. Then she blots all five holes, goes to black, and bares the field as they walk off. The five-hold screen returns, though, on tape, and the people move as if in some surreal baseball game. The participants point out that they had to run between rocks on the right, whereas they could walk on the left, to cover the same screen distance in the same time—a slight scale shift. On the right you see a full body; on the left only part of a torso. Kurtz says that they drew the shapes out on the ground. One was an O; another was an elipse; a third was almost a diamond. The circles keep the people apart, and the shutters wipe them out; but the talk continues in the dark. Here exploration has led to a mysterious image of real life.

Piecing together a person’s life from small glimpses, gradually moving to an overall sense of her, in Letters from Aunt Ethel, Holt reads selections from mournful letters, accompanied by a veritable slide show of shots of Aunt Ethel’s house. The droning voice announces small disasters: “My gutters are rotting. . . . The curtains fell apart, they were so rotten. . . . I still haven’t rented my tenement. . . . A few weeks ago I had an accident . . . Leo’s in the hospital.” We hear year after year of pains, problems, peeling paint. She marries Alec, eighty-eight, “a very nice wedding.” Alec dies after two months; the house is broken into; the money intended for the undertaker is stolen. “I am still alone,” she says, and picks out her coffin. Someone pulls up her fence. The skylights are giving way. “My yard is full of roses.” The slides withdraw. The picture goes to snow. Very sad; very comic.

Holt’s funniest piece, though is a takeoff on meetings between East Coast and West Coast artists. Robert Smithson represents San Francisco, giving a deadpan and persistent parody of the dig-it culture, and Nancy Holt overplays the snobby, elitist New Yorker. She asks why he’s come to New York and he says, “I don’t know—it’s really a trip—I don’t know where it’s at—I gotta psych it out—I just got in from LA—I just bought ten bicycles.”

Nancy Holt interjects, “Oh, yes, well, that’s a very nice idea, bicycle riding with ten bicycles.” She explains that he could turn that into a show of system art.

“I just want to ride the bicycles,” he says. “I don’t care about systems. . . . I’m just out there doing my thing—I just want to get a ranch out in the Fresno hills.”

“You have to define yourself more.”

“Definitions are for uptight types.” He goes into a long, druggy attack on head trips, bad trip people. “You’re just overly civilized, that’s all. You think too much. Why don’t you stop thinking, why don’t you start feeling?”

“You sound like a philosophy book.”

“I just move with it.” Goaded more, he asks, “Did you ever take acid? You’re not human. You should go out and visit the Indians.”

Hilarious and accurate, this 1969 down-at-heel, improvisatory performance stings with memories of Smithson’s death. As he was surveying a giant earthwork, his small plane stalled and crashed. Death is no photo; the frozen moment melts. Holt’s best work stems from her willingness to play off other human beings, rather than knobs and patch cords. She teases audiences, making them strain to see; she uses video for what it does well—fuzz. Her work is friendly to the cast and audience, moderately active, and self-aware.

From Jonathan Price, Video Visions: A Medium Discovers Itself. New American Library. 1977.

About JonathanReviewed in Videography, November, 1977; New York Times by Jeff Greenfield, December 18, 1977; Performing Arts Journal, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring - Summer, 1978), by John Howell; Leonardo, Vol. 13, No. 3 (Summer, 1980), by W.H.M Kaiser.

LinkTree: https://linktr.ee/jonathanreeveprice

MuseumZero site: www.museumzero.art

Twitter: http://twitter.com/JonathanRPrice

Instagram:

Pinterest:

Facebook:

Linked In:

Amazon Author Page:

Goodreads:

https://www.goodreads.com/author/show/41600924.Jonathan_Price

Video Pioneers William Wegman & Man Ray

William Wegman and Man Ray,

William Wegman and Man Ray, Spelling Lesson, 1973

William Wegman and his dog are star comic performers. Wegman’s tapes burlesque educational TV, PBS narratives, and conventional TV commercials. He derides these standards by imitating them--with goofy gags.

As one video opens, a dog lies in bed, near a very prominent alarm clock, his paw sticking out, snoozing in genuine sleep, while we wait for the alarm. The bell goes, and his head leaps up, then he snorts, and jumps out of bed.