V.R. Christensen's Blog

November 22, 2025

A Plot with a Few Holes

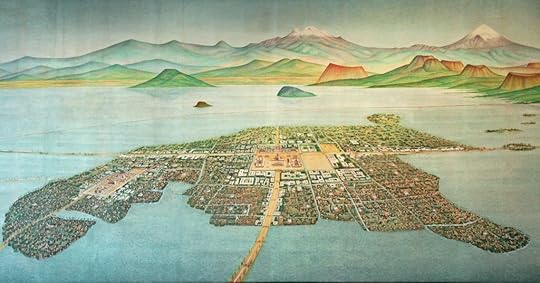

The cracks in Prince Nanzeta’s tale begin to show in July. Perhaps he forgot his story (unlikely) or, possibly, someone in one of his audiences somewhere pointed out to him the fact that the Sacred City of the Aztecs, Tenochtitlan, was actually located in the center of a lake with water all around. The landscape he had described replete with craggy cliffs and bottomless crevasses sounded, in actuality, much more like the royal seat of the Incas, Cuzco, many miles south in Peru.

In August, the “prince” arrives in Butte, Montana, maintaining his Aztec story and, for some reason, linking it to the Incas as if the two tribes were interconnected, somehow, friendly neighbors, though 2,800 miles apart in distance.

At this point, too, he takes on a much more arrogant air than he did in Denver. Where in Colorado, his reasons for condescending to commune with commoners was a necessary ruse that explained his eagerness to sit and spin his yarns for the pleasure of his fellow hotel guests, here, in Texas, followed by Montana, and then in Oklahoma, his attitude begins to feel decidedly more arrogant.

“I come from an aristocracy older than America and its people, and I have no place in my regard for time in my calendar to associate with the baser elements of American Society.”

Where before he admired the common man because he was not false and base and pretending at a nobility they were not naturally heir to, here he’s actually looking down on them as less than him, and making them feel it, too.

Here, too, the story takes on a few additional chapters, including the prophecies of “Red Blanket”, a Yaqui medicine man who had foretold of Nanzeta’s birth in the Aztec temple and how that young man would come to be a great leader of the Yaqui. He also includes a story of how a tribe of Pueblo tried to poison him by throwing snakes on him while they performed one of their snake dances.

Sometimes a tale is too tall to be believed, and the early Nanzeta seems to have understood this. Perhaps his success got to his head, or possibly he was becoming bored of his own story. It’s possible, too, that he simply enjoyed the thrill of convincing people to believe in something that was so obviously a lie.

In Dillon, Montana, our medicine man makes a slight alteration to his name and signs his name in the guestbook as “Manzetta” in with an “M” rather than the usual “N”, though this could simply be journalistic error or even difficulty reading the “prince’s” signature. Beneath his name someone wrote “Reggiano Parmesiano, Duke of Parrlle, Italy”. No doubt this is simply a joke, but it does leave one to wonder if they saw the name and thought to mock it by adding the next entry or, rather, if they saw him and thus were providing subsequent guests to understand that the young man was more likely Italian than Aztec. It’s possibly a clue to his origins. More likely it is one of several dozen red herrings provided by various means as this man’s story unfolds.

It’s here, too, in Dillon, that Nanzeta provides an explanation as to why he might be so bold (or ignorant) as to confuse his Inca heritage with his Aztec one. He is on record as saying that his mother was Inca and that she was of Peruvian royalty, whereas it was his father who was the descendant of Montezuma. A convenient (and necessary lie) but hardly a believable one.

When asked how he spoke English so well, he said he attended Stanford, but upon adding that he has made a tour of the world, he was asked at what age he managed to complete not one course but two at college. His answer is that he began Stanford at the age of fourteen.

At times, the narrative diverges for reasons apparently beyond boredom. It’s as if the challenge of remembering all the details of a fabricated story becomes too much. If one takes the early accounts of him, those which illustrate a very young man, hardly an adult, bearing an outlandish and yet streamlined narrative, challenged, yes, but patiently and graciously defended and compare those with the accounts that come in six months later with their alterations in spelling, the bizarre side stories and interjections of a contemporary but geographically distant and quite separate history and a much more hostile personality it seems possible, perhaps probable, that there are two actors rather than one. Only the descriptions remain identical. Or at least nearly enough so to suppose it is the same person, and it isn’t as if his description is of the ordinary kind, either.

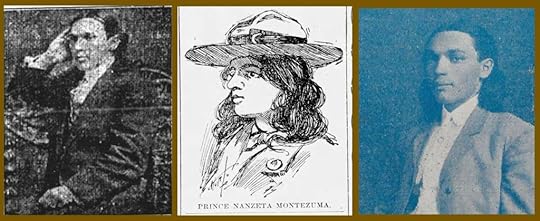

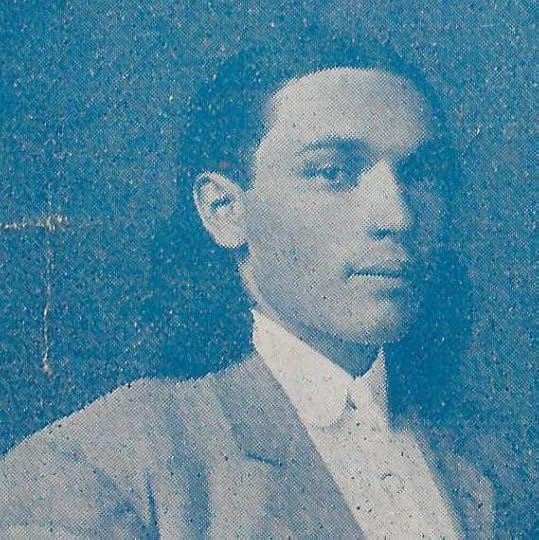

In April and May in Denver, he was described as “A dapper, long-haired, dark skinned Mexican youth, and “a swarthy young man, with very long and black hair”. A line drawing is included, as well, which is useful but not entirely decisive as to his identity (what do you think).

As to his age, it varies somewhat. For instance, in Denver he is 23 and then, later in that same month of May, he is 22. In Spokane, he was “said to be some 30 years but his looks belie that statement and 15 would come nearer what he appears”. In Butte, in August, he “looks not over 25 years of age.” In Oklahoma, in December he is described as “a small, dapper appearing young man of about 20.” It seems to me that these discrepancies are the difference between what he told people and what he appeared, and the line between the two is sometimes vague, but his struggle to be taken seriously on account of his apparent youth in contrast with the expertise he claimed was a sore spot for much of his early career.

In several reports of his appearance, scars are described, particularly when they were used as evidence of his adventures. In Butte he is said to have suffered a “bad cut on the back of his wrist” with a scar to prove it. In Salt Lake, he displayed a scar on his temple, where a bullet grazed it. In October, in Galena, Kansas in October, he showed off two scars on his right arm as proof of a saber wound during his duel with the Mexican soldier.

Another clue is offered in the descriptions of his speech, though it’s uncertain how reliable these are. In Butte in August he spoke with a “charming voice and beautiful English, bearing only the slightest accent” and “as an educated gentleman of refinement, fluent in speech and apparently well informed on all of the things he talks about.” In Dillon he was said to have spoken “with a foreign accent, but occasionally lapses into his native American tongue”. In Payson, Utah in September, his voice was described as soft and mellow with “a rich accent”. In November, while in Texas, his pronunciation was decidedly Spanish. December, in Oklahoma city, he told his story “in perfect English.”

Two marked exceptions occur in, however, in these descriptions of him in this first year of his “advent”. In one account while staying in Galena, he was said to have blue eyes, though the other newspaper accounts of him contemporary to this time identify him quite plainly as a Mexican, which would have made blue quite extraordinary, and may have simply been an error in transcription from written notes to typeset. The second detail which varies pointedly from the other accounts occurred in November in Hempstead, Texas. Here it was said as he was chased out of town that “his wig came off as he ran away”, but as the article, and those written around this time, were highly satirical in regard to the “prince”, I suspect this is a theatrical invention for the sake of sensationalism. However tongue-in-cheek this episode of the “Prince’s” career was reported, it’s worth describing in detail, for its here the “prince” appears to come into some real difficulty. The story begins much like it did in Denver, where he arrives at the hotel and makes an impression.

Arriving there on a recent night, the prince registered at the principal hotel, and by his appearance attracted a lot of attention. His foreign air, combined with his flowing hair and Spanish pronunciation, produced a powerful effect on the minds of the Hempstead people—they thought he was a real bona fide prince and were prepared to pay him the homage due to one of his exalted station.

He tells his stories and impresses his audience to the degree that they once again are moved to pay for his meal and to ply him with drinks and everything that can be offered him.

In the morning, however, the guests of the night before were greeted by the sunrise and “the rude shattering of the dreams which accompanied their sweet slumber” upon finding him on his box selling his remedies. “In his hand he held a quart bottle which he was loudly proclaiming as the only genuine cure for all the ills to which humanity is heir.” (A common claim.) He went on and on making wilder and wilder claims, and introducing one bottle after another, each containing an elixir more powerful than the one before it. The first cost the audience $1 each, the next was $5, but with a coupon was half of that if they returned the first bottle. Soon he sold out and pocketed what a group of skeptical onlookers assessed to be about $100 (a “century” in street-hawking terms and a good day’s work) and, “with a sweeping bow” stepped off his box and closed up shop. As he was putting away his wares, the group of skeptics, insences on behalf of the fools who had fallen for his act, they charged after him, chasing him with out of town with empty cans and firecrackers and a dog.

Down the road went Prince Montezuma, followed by the said hound and half the populace of the town. In the hurry of his flight, his wig came off and this was greeted by a fresh outburst from the pursuers. He made two jumps to the dog’s one and finally won out in the race by landing in an unused Pullman car from which he could not be dislodged. Prince Nanzeta di Velasco Montezuma, Prince of Incas, left Hempstead on the night train a sadder but a wiser man.

By the time he arrives in Oklahoma City in December, news of his preposterous story and the discovery that he is a “fakir prince” and a peddler of snake oil and corn cures has preceded him.

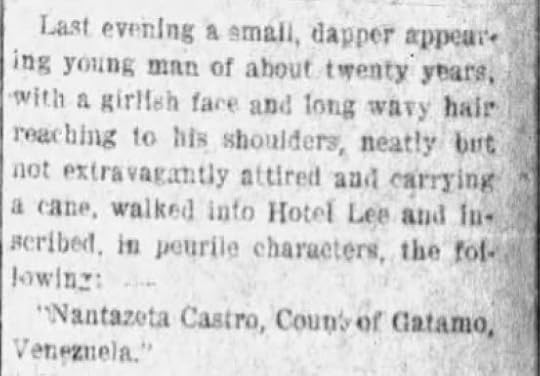

As if to lean into the part, he goes possibly a step too far. The name he writes on the register of the Lee Hotel is “Nantazeta Castro, Count of Gatamo, Venezuela. When asked to account for his credentials, he seems to lose the plot and claims that his name is the cousin of the Venezuelan president Cipriano Castro and, furthermore his people were the “Swiss of Venezuela”. Here, in his retelling of his history, the woman he has fallen in love with is not Mexican but a New Yorker whom he met while she was visiting Venezuela.

What is this sudden need to lay claim to a white identity? And yet, despite no mention of his dark skin, the description is the same.

Last evening a small, dapper appearing young man of about twenty years, with a girlish face and long wavy hair reaching to his shoulders, neatly but not extravagantly attired and carrying a cane, walked into the Hotel Lee…

The Daily Oklahoman, in reporting on the “prince’s” visit, took on an air of apparent suspicion and at times mockery.

He scarcely finished the signature when a commercial traveler stepped up to the princeling and with a smile of recognition, explained: Hello! You there! The last time I saw you, old man, you were selling resurrection plants over at Webb City, Mo.

Even though he had come to Oklahoma City to do something very similar, and had seemingly few qualms about letting his Denver friends know, he took a decidedly defensive tone, denied the whole and proceeded to explain, in perfect English, that he had never been to Webb City, and when a reporter presented his card to the “count’s” door some time later, he was more than prepared to make the story bigger and more elaborate than ever before, intermingling with wild abandon the ancient histories of Mexico, Venezuela, Peru, the descendants of Inca, and the tribe of the “Loqui” (there is no such thing, though, again, this could be journalistic error) as if they were all guests in a politically fraught ballroom rather than civilizations occupying three different continents.

The last straw in the article of that day was the last line which read, simply, “The police kept close watch on his movements all night.”

This left the “count” apparently incensed. He sent a line to the editor demanding an apology. And they did, though with a good bit of irony and sarcasm.

The count asserted that he considered the write up which he received in yesterday morning’s Oklahoman an insult, and cited as cause for grief the last two lines …

We apologize for this, and think perhaps the police should not have done it.

The count last night admitted he had sold medicine at Ardmore, and we apologize for that.

He said last night that it is the custom of his country for the people to wear long hair as it is a part of their religion and he felt that he had a right to wear long hair if he so desired.

Now, we deny having uttered or indited anything insinuative or disrespectful of the count’s tresses. We didn’t do it, …

(They hadn’t.)

… for we have long since avowed with Pope that

“Women man’s imperial race ensnare

And beauty draws us with a single hair.”

We also lament our own ignorance in supposing there were no counts in Venezuela or among its aborigines, but can readily realize now that the South American Indians probably took their cue from the play entitled “The Count of Montezuma,” a rank fake on Dumas’ “Count of Monte Cristo.”

The count’s casual admission that his title was an empty one caused us to surmise the existence of other vacuums but we apologize for that also.

The count also alleges that he is an actor, and as we are willing to concede that fact there is no room for apologies on that score, at least not from us.

It’s in December, however, in Oklahoma City, where the first major deviation in the “prince’s” story takes place. Up to this point, there have been additions to the story. It has certainly grown and become taller and more “epic:” in nature, but a crossroad seems to appear in Kansas that begins, if not to change the trajectory of the story, at the very least to confuse it. It’s here things begin to get strange and the quest for the truth of Nanzetta’s identity and origins seems impossible to pick out of the detritus of lies and deception.

It happens while he, as on previous nights, is sitting in a hotel as a crowd of eager listeners surrounds him. It is here he claims he spent many months on an expedition led by the great English explorer Harry Landes to Thibet and there “penetrated into the wilds of that country further than whites had ever ventured before.” It’s a mere mention in The Daily Oklahoman, but it’s one that will take on a life of its own, given time.

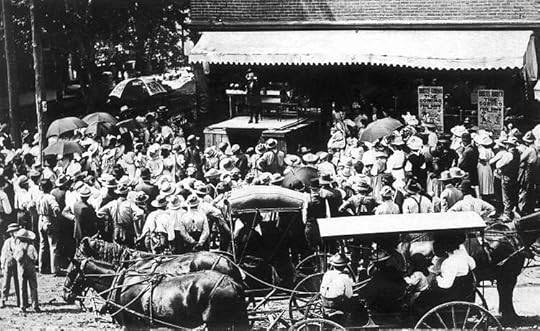

But first … a little about the phenomenon that was The Great American Medicine Show.

November 5, 2025

The Advent of Nanzeta

Stepping from the noisy street into the almost crowded lobby of Denver’s Albany Hotel, a gentleman has just entered. With a walking stick that he lightly touches to the ground (he’s far too young to require its aid) he crosses the room and presents himself at the counter. He slides two silver dollars toward the clerk and signs his name in the guest register while the clerk eyes him with apparent curiosity—and perhaps, too, some suspicion. His prepayment for the room is meant to earn him some good faith. It’s also meant to allay any too-personal questions. He is here on business—what that business is, for now, is for him alone to know.

The clerk, having selected a key from the wall behind him, now slides the guestbook toward himself and turns it so that he can read it clearly and without effort. And while the man is thus occupied by the letters and names and titles only moments ago scrawled there, the gentleman half-turns and leans against the counter, allowing those who have gathered in the hotel’s reception room to observe him. Everything about him, from his tailor-made Prince Albert suit of buff tan, to his perfectly groomed hair, long and black and hanging to his shoulders, to the large Panama hat with its unusually wide brim, to the jeweled rings he wears upon his delicate and pristinely manicured hands, is intended to make an impression. So far, his efforts appear to have succeeded.

The clerk clears his throat, recalling the gentleman to the business at hand. “A two dollar room,” he observes. Not the best. Far from the worst. “Are you traveling alone, Prince …” the clerk looks at the guest book once more. The name is a remarkable one if not exactly easy to remember—or pronounce.

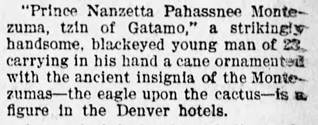

“Prince Nanzetta,” says the gentleman, helping the clerk out and, at the same time, introducing himself. “Prince Nanzetta Pahassnee Montezuma, tzin of Gatamo.” His voice deep and even stands in direct juxtaposition to his elegant, almost feminine features—and his brown skin.

“Tzin?” the clerk inquires cautiously. Is his temerity the product of incredulity or humility in not knowing or understanding the meaning of the title?

Before the young guest can answer, a woman approaches the desk. She leans her bosom against it. Her gray hair is perched upon her head like a bird’s nest and her heavy earrings drag her lobes toward the earth. She looks at him, quickly, like a hen, and sends her jeweled lobes swinging.

“You are a prince?” she asks him. “Prince of what? Of where?”

Her doubt in his claims is quite apparent, but the large and inquiring eyes of her companion, a young woman who, from her place mid-way across the room, is staring at him in want of a satisfactory answer.

He has not yet decided to give one.

“You look like a Mexican, though a well-dressed one at that,” she continues before he can answer her. “And I suppose you are very handsome for all you could be my great grandson.”

He is unruffled. He has nothing to prove to this commoner. At least he is confident in his ability to do it. He turns back to the hotel clerk.

“I will rest until dinner. My room key, please.”

He is handed it.

“I hope the is to your satisfaction,” the clerk says, half-sanctimoniously.

“I will be sure to let you know if it is not,” answers the guest. He turns then, offers the slightest nod to the old woman and a slightly more significant one to the young woman who is still watching him and turns from the lobby in the direction of the staircase. He might take the elevator, but then his ascent would be invisible to the still watching and now captivated crowd.

In his room, the young man rests and he reads—books on Mesoamerican civilizations and explorations into the remote and forbidden regions of Asia. In time, a card is presented at his door, and then another and another. Denver’s genteel class, having heard of the mysterious stranger’s arrival, have come to dine at the hotel’s restaurant and to have a look for themselves at this so-called “prince” of the Aztecs. He will not dine alone tonight. He will eat the best that the hotel has to offer, and he will do it amidst the best company the city can muster. The prince accepts these invitations and sends a message to the front desk. Tonight the common table will be set in preparation for a royal dinner.

After he has bathed and dressed, has combed his hair to a sleek shine, and has dressed again in the garb of a royal exile, replete with jeweled rings and a diamond incrusted horseshoe pin which he wears high upon his cravat and with the heel end downward. Why save up good luck when you could benefit by it today, after all? He examines himself once more in the mirror and finding his reflection satisfactory, he leaves his room for the dining room. He is not the first to arrive there, but neither is he last. He takes his place, not at the head of the table but at the center of it. He may be a royal, but he is a democratic one, preferring the company of the middle and upper middle classes to those of the elite, in the United States or anywhere—and so he will later tell them. He makes a mental note to do so, but the script is so well memorized by now that it requires little in the way of remembering. He, Nanzetta, is the prince of Montezuma. What is there to remember?

At the table, where a few have been seated already, others arrive, and soon there will more than the table can comfortably hold. If the reception room is not filled to standing-room-only it is not filled, such is his motto.

The prince orders the boiled tongue with chili sauce, and he eats as the Continentals do, with fork in the left hand and knife in the right, not because it is what he has become used to as a royal, or as a result of his many and varied travels around the world, but because it shows off his jewels—and his hands—to best effect.

All eyes are watching him, some directly and studiously, others more surreptitiously. The questions begin, though they are innocent enough at first. How does he like Denver? How long does he intend to stay? What is it that has brought him here?

He is, just at first, evasive, paying more attention to his meal than he is to his companions, and yet eating carefully, slowly, cutting small bites and chewing them thoughtfully.

More gather and the table fills. Among the guests is the woman with a birds nest for hair and her young charge. Standing nearby but apart, not seated, not here to eat but to do their work with pencils and paper are four or five newspapermen ready and eager to share the news of the prince guest with the citizens of Denver and his riveting history, too.

They are soon so eager for his story, that one of them asks him outright.

“What gives, Prince? What is your story, anyhow?”

“Yes, tell us,” another chimes in. “Where are you from, and what has brought you here?”

“Oh, please, tell us about the land you are to inherit?”

This last from a pretty young woman who bats her eyelashes at him and blushes ferociously. It is a request he cannot not resist, and so he clears his throat and begins his romantic tale.

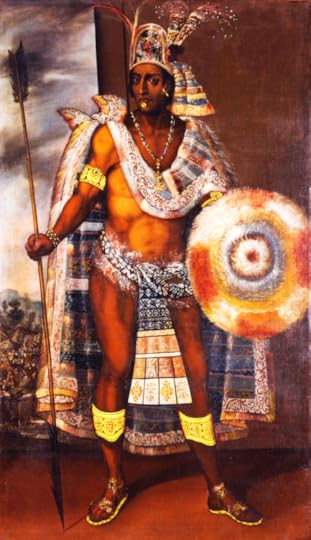

“I have come to this city on business,” the prince begins in perfect English only delicately laced with a Spanish accent. He will not say just what the business is that has brought him. Not yet. “And I have come here by way of a long journey, wherein I have visited many countries and have sought to educate and inform myself on the ways of the world. Most recently I have visited the Pacific cities from Washington to California. But my home,” he says, taking on a decidedly more melancholy tone, “is located in the southwest portion of Mexico in a small independency just north of the Yucatan known for centuries as the Sacred City of Tenochtitlan.” The exotic name is not an unfamiliar one, but its mystery and remoteness serve his aims perfectly. His audience is mesmerized, and he has only just begun. “I am a descendant, the last, even, of the great Montezuma, and one day I will inherit the city and my rightful place as ruler of the people there, the remnant of Aztecs whom Cortez sought to destroy.” He paints the picture. “Tenocthitlan is located in a fertile valley 180 miles long, surrounded on all sides by rocky gorges, and death-inviting morasses and further fortified by a wall which no alien race has successfully penetrated.

“There are some 80,000 of us who live in the Sacred City,” the prince continues after taking a moment to delicately sample his food. “That is all that is left of the great nation that once numbered 80,000,000. Cortez thought he’d vanquished us all, but it was not so. And now, …” the prince pauses for dramatic effect. “What Cortez failed to finish, President Diaz of Mexico is determined to do.

“Between our land and that of Mexico is a stretch of neutral desert inhabited by the Yaqui Indians,” the prince continued. He takes a sip of his drink and slowly sets it down, thoughtfully “recalling” his home and the story of his people. “The Yaqui are poor and have been kept in a state of oppression by the Mexican government. They are said to be fierce savages who have no desire but to murder and plunder, but such is not uniformly the case, and when it is, it is due to the state of desperation in which the Mexican government maintains them. The Yaqui, desperate for reprieve, came to find sanctuary in the neutral lands, but the Mexican government, determined as they were to keep the Yaqui under their thumb, followed them and entered the neutral territory. There, the soldiers committed such atrocities upon the tribe that our people offered to help them. My uncle was placed in charge of a small but determined army of Yaqui. I loved my uncle dearly, for he had sent me to California to be educated, and so, to repay him and demonstrate my love and devotion to him, I begged him to allow me to accompany him. I was young then,” the prince says and pauses to gauge the audience’s response to this. He dares someone—anyone—to comment upon how young he looks now, how impossible it seems for him to have accomplished so much at such an apparently young age, but no one does. “Having returned home to these newly arisen difficulties,” the prince continues, “my blood was full of a sense of duty, but it was full, too, of youthful vigor and naivete’. I wanted to show my uncle that I was prepared to earn my inheritance, that I would become great like my father and like the Aztec kings before him. He granted my request, and together we marched northward, my uncle, myself, and a hundred strong Yaqui soldiers.

“Upon arriving in Mexico City, my uncle, accompanied by six brave warriors, determined to find the leader of the Mexican army and reason with him or die trying, I was left to stand guard, and thus I did. The meeting lasted hours, then days, and as I kept my vigil, I happened to meet a daughter of one of the senior officials as she came and went providing refreshment to her father and his brethren in arms. Our brief conversations turned into flirtation, and soon I found myself earnestly wooing her. We fell in love, but I knew my family would not approve of my marrying so far beneath me.

The meeting ended, and I was called away. I expressed my desire to my uncle and then to my father, but I could not persuade them to support my desires. I tried to give it up, to devote myself to the duties before me, but then I learned that of the evil deeds of one of the Mexican soldiers who had lured her away from the city center posing as myself, and there he had made his own case. She refused him. Incensed by her refusal, he murdered her! Fury filled my heart upon hearing this grim news, and I swore to vanquish her assailant!

The prince allowed himself a pause here to collect himself and to provide the emotional evidence that would guarantee his story was felt. He laid his hands upon the tablecloth and, closing his eyes, he took a few steadying breaths.

“I was soon gratified,” the prince continued at last, “to see that the bond between myself and my brothers, the Yaqui, was made strong by my service to them, and as I had so faithfully carried their cause, so too were they prepared to adopt mine. And so a small band of us—I quite consider myself one of them now—ventured out on a mission of revenge. I returned to Mexico City, and sought the villain out, but upon hearing of my pursuit of him, he fled the city. I followed him from place to place. At last in the southern part of Mexico, I caught up with him, and the meeting resulted in a vicious duel. The officer was not as skilled with the knife as was I, and so, to hedge his bets, he had armed himself secretly with a pistol. He fought bravely, but he was no match for my quickness and skill. When it seemed certain that I would win the struggle, he pulled out his gun and took a shot, grazing me in the temple.”

For the sake of his wide-eyed audience, the prince stops a moment here, and with two bejeweled fingers he pulls aside a gleaming tress of long black hair, like a curtain over a precious work of art, and displays the proof of his injury by way of a long, shiny scar on the side of his head.

“The gun must have been a last minute thought of the soldier,” the prince continues, “for there was but one bullet loaded, and so he threw it aside and returned to the use of his knife as a weapon (whether I was gentleman to let him retrieve it or fool, I’ll let you decide) and so the struggle continued. I managed, in the end, to win,” he says and pauses to exhale a breath of reminiscent exhaustion, “but not before suffering a deep gash to my wrist.” Again, he offers a scar for consideration.) “And a nearly fatal wound to my side.” The prince pauses once more, but the revealing of once-injured flesh has come to an end. His piercing black eyes stare blankly at a spot on the table. He shakes his head slowly as he recalls the words of his story more than the scene itself.

‘To answer for the murder of the soldier,” he begins again, though slowly, dramatically … “a bounty was placed on my head. And so I fled for the U.S. border. I was nearly caught on several occasions, but at last I reached Austin. And there, in a hospital, I collapsed and there remained on the very bring of death for many weeks. I was nearly recovered when I fell ill again, and I was not wholly recovered from that when I left the hospital for fear of my life, for by then the bounty hunters had learned where I was and had come to find me.”

The prince scans the crowd then. Should he continue? He could, for he has more of his story to unwind to a ready audience, but he sees that not everyone believes him quite completely. The story is too wild, too tall to be bought wholesale by everyone. The pretty young lady across from him looks as if she is prepared to (or perhaps she has already) shed a tear for the poor, unfortunate prince. He offers her a smile of gratitude. With his full lips and round face free of even the hint of stubble, he does appear much younger than he actually is (though not as much younger as he pretends for the sake of the necessary experience his story—and his occupation—requires). But he is handsome—“a striking figure”, the papers are wont to report—and he knows his power to leave an impression upon the impressionable. He decides that enough is enough for one night, and so provides the necessary close to this chapter of his tale.

“So long as there is a bounty on my head,” he concludes, “there is no chance of my returning home. There is but one path to the Sacred City, and the soldiers of the Mexican army guard its entrance carefully. Until there is a change in government, I am a lonely exile, a prince without a country, and a homeless, wandering wretch.”

He places his napkin on the table, and exhaling in punctuation to his sorrows, he hales the waiter … but, and as planned, he finds he is not allowed to pay for his dinner, nor for his room for the remainder of his stay. The money, more money than is required, is offered as a stipend toward remunerating the poor prince for his difficulties. He will sleep more peacefully tonight, it is hoped, for knowing he has friends in this, his adopted home, for as long as he wishes to remain, a night or two or three… Not longer. No, not longer.

But what could he give them in return? Why, he had already given it by way of the honor of sitting in company of a prince for a few hours. An honest-to-goodness prince! Were they not just a little more royal for having sat in the presence of royalty?

He rises from his place at the table and offers his heartfelt gratitude for the generosity of his new friends. Just as he is about to quit the room to retire to his own, he turns, and, almost as an afterthought, offers an invitation.

“In the event you are interested,” he begins and pauses for dramatic affect … “tomorrow, on the square before the courthouse, I will be telling a little more of my story, of my adventures, and sharing some of the wisdom I have learned both in my education at Stanford and in my life among the Yaqui, for they have truly taught me more than any university could do. And the skills I have mentioned, those which kept me alive, and those which provide me bread in this chapter of my life, I will have on display. Do, my friends, consider coming to see me there.”

The audience, some of them, a good few, appear receptive to this invitation. The pretty young woman is blushing and blinking and fanning herself. Her guardian, the woman with the bird’s next for hair, appears less convinced but, to his great pleasure, not entirely opposed.

He bows then and turns from the room.

The next morning, Prince Nanzeta’s courtiers found him, mounted upon a box and extoling the virtues of some elixir he swore could and would, he guaranteed it, heal any ill.

In glowing words he told how such a one had been cured even when the undertaker had been telephoned for to take his measure. He said that the medicine would not fail, being based on such a principle that but one minute portion was enough to make Ponce De Leon shed tears of sorrow that it had fallen to the lot of another to discover the fountain of eternal growth. He expatiated so largely upon its merits that a few were induced to buy.

Men and women of the crowd began to buy, and as they parted with their one dollar bills, the next and superior cure was produced so that they traded the one in for the next until, at last, he sold out. Some of his audience from the night before, the young woman and, perhaps, even her elderly guardian, were induced to buy. The man was a student of medicine, after all, and an apprentice of the Yaqui medicine men. Why should he not make his way in this world by the knowledge he had gained?

Still others, upon seeing this lowly and pathetic display, were either woken from their dream or validated in their suspicion that the man was a fraud. Either way, Prince Nanzeta cleaned up, and, having sold out, he packed up his things and moved on. The next stop? Galveston, Texas, where the story, with a little help from a friend, begins to fall apart.

1902

In the spring of 1902, the character which would become known as Prince Nanzeta[1] appears to have arrived fully formed in Denver, Colorado. Undoubtedly it was a practiced part and had been played many times before, but for whatever reason, the occasion of a Mexican prince’s arrival in a Denver hotel seemed a significant one. Many believed his story. Others understood him to be an impostor, but they watched and listened and played along with the charade, nevertheless. The young prince, at least on this first occasion, took his audience’s doubt in stride and subsequently played to their weaknesses. His story was a sad one, his plight filled with tragedy and survival against all odds. He was charming, elegant, convincing, utterly unruffled by accusations of an ulterior motive, completely mesmerizing, “strikingly handsome,” and, at the very least, seemingly harmless. And in the days before television and radio, he was an entertaining and welcome distraction.

No fewer than four Denver newspapers reported on the young “prince’s” arrival, upon his claims of nobility and his story of exile, love and heartbreak, chivalry and death-defying duels, bounty hunters, and his lonely wanderings after being exiled from his home and the land of his inheritance. The story then spread by train and by telegraph, and by the time Prince Nanzetta arrived in Montana, six months later, reports of him had been published from coast to coast. One article which ran repeatedly over the course of three years appeared in more than seventy papers nationwide.

The first accounts of him were consistent in their description of the man who might easily be mistaken for a woman, with his fine features, his diminutive stature, and his small hands and feet. One account even described him as frail. Certainly, no description of him failed to mention his long and lustrous black hair which fell in waves to his shoulders. Those who reported on his arrival in Denver, and then later in Omaha, Butte, and Salt Lake City described him as a dapper, dark-skinned Mexican youth with a mysterious air of suavity who possessed piercing eyes. In his tailor-made (made to fit) Prince Albert suit of tan and a wide brimmed hat, he presented himself as a “well-dressed Mexican”. As an accessory, he carried with him an intricately carved cane, and he held onto it with fingers that were weighted down by several rings of large and apparently authentic jewels—diamonds, rubies, emeralds, opals, and pearls. He spoke with a “charming voice” of “beautiful English, bearing only the slightest accent”, which, together with his “aristocratic features” left quite an impression.

As to his age, there was some variance in the accounts. He was sometimes twenty-three, at other times a year older or younger. Once in 1902, he claimed he was twenty-five. The Paducah Sun reported in August of 1902 in regard to his arrival in Spokane, that “[T]he young man is said to be some thirty years of age, but his looks belie that statement and fifteen would come nearer what he appears.” Indeed, his appearance of youth seems to have been an obstacle between himself and his aims (and his claims) for the first several years of his career as a seller of remedies.

The accomplishments he claimed to have acquired during those years was impressive—perhaps too impressive. Apart from the skills necessary to tell his wild and fantastic story (specifically, the skills of being a famous duelist, proficient with a knife and a pistol, and a world traveler who had seen some 39 countries) he had been educated in both law and medicine at Stanford, spoke several languages fluently, he was an expert ping-pong player and virtuoso violinist. On one occasion he boasted of having established a hospital for Mexican exiles in Salt Lake City. Of his many claims, one, at least, is true: he was a talented and convincing actor.

As an actor, he was perhaps unparalleled in the world of medicine shows and quack cure pitchmen. Unlike other medicine men who either sold their wares as an extension of their exaggerated but otherwise ordinary selves or, in contrast, those who donned a temporary costume for their street or tent performances, Nanzetta became his act. Perhaps he believed it or grew to believe it. Or, just possibly, a portion of it was true enough that the rest was simply a fanciful elaboration. Certainly, it was much easier to convince your audience to believe your story if you, at least in part, believe it yourself—as he appears to have done. His coolness under examination and his quiet and elegant manner, at least as it was described by eyewitnesses, belies a regalness, at the very least an intelligence, that is difficult to fake.

Of the dozens of newspaper accounts that describe Nanzetta’s early appearances, there is an almost consistent through-line. The descriptions, hardly of an everyday average person on the street, all seem to perfectly describe the Nanzetta of Danville, Virginia. Though the tale he weaves in those early months appears to grow and evolve, it’s impossible to know which of the details is merely an example of something more added by one reporter than another and what is truly a newly invented chapter of the “prince’s” story. By August, a few conflicting details begin to enter the picture, his name changes in spelling (though whether that is an intentional deviation by Nanzetta himself or simply an error of reporting, it’s impossible to say) and the Inca people are referenced, sometimes in addition to and sometimes in replacement of, Aztec. It’s shortly after this that things begin to break down and the “Prince of the Aztecs” narrative begins to fall apart. Before we pick apart his story, however, we must first lay down its foundational elements.

What follows is a dramatized account of the prince’s arrival in Denver on the 27th of April, 1902, pieced together from the more than thirty newspaper articles which reported on “Prince Nanzeta” and his travels through the Southwest in spring through autumn of that year.

[1] When he first appeared as an Aztec prince in 1902, and for several years thereafter, the spelling of Nanzetta’s name was inconsistent. Eventually, there was a splitting off of the Prince Nanzeta identity from the one of Dr. Nanzetta, and so, when I refer to the “Prince Nanzeta” character, I will use one “t”.

October 28, 2025

My Introduction to The Great Nanzetta

It was in my work writing for a local history blog in Danville, Virginia that I ran, quite by accident, into the story of Nanzetta. I was actually researching another story, one about a man named Edgar Stripling who had committed murder in Georgia and was on the run from the law. Having escaped from prison, he fled to Danville where he adopted a new name and was elected Chief of Police in 1907 before eventually being discovered and taken back to Georgia after fourteen years on the run.

In scouring the papers for as much information on the Police Chief Morris as I could gather, I ran into an article that described his arrest of a man wanted for forging a check written by the Indian medicine doctor J.H. Nanzetta. I did little more at the time but make a mental note of the curious name and equally curious occupation.

It wasn’t long after that that, while researching for a post on patent medicines and weird cures of the past, that I ran into Nanzetta again … and again. Not only did he advertise extensively in the papers, but he seemed to be always in trouble with the law. The Edgar Stripling story had taken place during prohibition and during a time of rapidly changing laws around the practice of medicine and the manufacture and distribution of drugs, and so there was quite a lot to be said in the papers and in the courtrooms about Mr. Nanzetta’s wares and his wild claims about them.

I wrote up my piece on Depression Era Cures, but I wasn’t satisfied to just drop it there. I needed to know more about this Nanzetta character.

I did a little more digging and found someone with a similar name who appeared in a Denver hotel in 1903, identically described and weaving wild stories about his origins and adventures. His story, as I continued to dig, grew stranger as his tales grew taller and ever more romantic. Over and over again, the papers described his remarkable arrival and the stories he spun. Sometimes they described his departure, too, when he was chased out of town as a quack doctor selling quack cures.

His story wasn’t purely consistent, though. It morphed and changed over time and as circumstances (and his need to evade the law) demanded. At times, particularly in the early days, Nanzetta presented himself as half-Mexican, but in time he settled on a Native American origin story (though the two are not necessary mutually exclusive). Throughout his thirty-year career as a peddler of patent medicines, he was identified (and identified himself) as Hindu, Italian, or simply and vaguely “foreign”. In one instance, Nanzetta, while on trial for peddling medicine on the streets of San Francisco without a license, claimed he had run away from a cruel step-father who had married his Mexican mother and who had sent him to an Indian Industrial school from which he had likewise escaped. In Danville, he refused to speak of his past.

Even after settling in the south where he maintained storefronts and manufacturing laboratories in South Carolina, North Carolina, and in Danville, Virginia, his true history was a well-crafted mystery and one he exploited. One advertisement offered a third person account of his reticence in speaking of his own past and which was undoubtedly written in his own hand, and read as follows:

When you inquire of Nanzetta as to his nationality, he will tell you that he is half Indian: if your curiosity is still unsatisfied and you ask him about the other half, he will quickly and emphatically give you to understand that that is his business.

This was The Great Nanzetta—that was all the public needed to know—“a real life Indian herbologist”, “the man who knows”, the “King of Dentists” who could pull teeth painlessly with his fingers, and the one to go to for the ointments, elixirs, pills, and unguents that would cure any and all of the “cure for all the ills to which humanity is heir”.

“Dr. Nanzetta with his eldest son, Leonard (who would later become a legitimate doctor) and Nurse Brown with whom he was said to have a romantic relationship.

Eventually, and somehow, Nanzetta found his way to Danville, first as a street pitchman, but later he settled and opened up a shop where he saw clients and prescribed cures behind a storefront decorated with the specimens of the tapeworms and teeth he had removed by aid of his methods. At a time when laws prevented just anyone from practicing medicine, he simply claimed he was “a doctor in his own way,” educated as he was by … Indian medicine men, or Himalayan yack herders, or Buddhists in the sacred city of Lhasa—depending on which fiction he was spinning at the time.

On several occasions he was arrested, sometimes for violence, sometimes for theft or fraud or malpractice, and at least once for sexual assault. He was married thrice, and all three marriages ended in divorce. At last, however, in 1929, the law caught up with him when he was indicted by the North Carolina Attorney General’s office for practicing medicine without a license. When they served him his charges, they did so under another alias, that of a Russian immigrant named Cohen, whose identity included a Jewish wife and children (and a sister) living in the state of New York.

Just weeks before his trial, Nanzetta checked himself into a sanitorium in Baltimore “on account of his nerves” and here, while under twenty-four hour watch, managed to find himself the victim of a gunshot to the head. Though his death was deemed a suicide, speculation regarding the demise of the once-famous Nanzetta flooded the newspapers. But the truth, like so much about the man, was lost in the confusion of untruths and half-truths and blatant truths told too elaborately to be believed and full-blown deceptions.

So how does one write a biography about a man whose history, even his true identity, is so thoroughly and even intentionally obfuscated? Maybe “truth” isn’t really the point, after all. Perhaps it’s the lore Nanzetta created around himself that is the real story here. Perhaps it’s the adventure of discovering what in this case, and perhaps in any other, “truth” means. It’s also possible that the story of the Great Nanzetta, Indian Medicine Man and Doctor-in-His-Way provides us with the opportunity to examine the psychology of belief and why we so often and so readily agree to be deceived. Who wins when a lie is successfully told? And who loses when the illusion falls apart?

Here, I attempt to pull the pieces apart and to expose the man, or men (and possibly women, too) who have made this mystery what it is.

Please join me as I embark upon an adventure that is equal parts historical detective work and biographical narrative, and that of one of the most fascinating characters I have had the good fortune to stumble across in my many years of historical writing and research.

Have something to add? Want to participate in further discussion? Interested in a deeper look into the cultural impacts and comparison to our current time? Come find me on Substack!

October 13, 2025

The Executioner of Danville

For a short time, between the years of 1896 and 1904, the city of Danville, Virginia was responsible for conducting its own executions. For the entire span of that time, one man held that position.

Patrick Henry Boisseau was born October 17, 1850 in Dinwiddie county, a descendant of French Huguenots who settled that part of the state in the late 1700’s. He was educated at Wingfield Academy before joining up to fight in the Civil War at the age of 15.

Mr. Boisseau first arrived in Danville with his brother, William, on July 1st 1870. William acquired the position of city sergeant and hired his younger brother as assistant. The two maintained their posts for seventeen years, until William died of pneumonia in 1888. Patrick then took his brother’s place as City Sergeant.

Amongst Mr. Boisseau’s responsibilities was the serving of summons to witnesses and jurors, which required miles of walking each day. He was also in charge of the care of prisoners, toward which he was famously generous, providing them lavish dinners on major holidays, which he paid for from his own pocket.

It was also a part of Mr. Boisseau’s responsibilities to perform the execution of prisoners sentenced to death for murder. It’s believed there were six hangings in Danville, of which Boisseau oversaw each. The only occasion on which he balked was in 1896 when Jim Lyles and Margaret Lashley were sentenced to hang for plotting the murder of Lashley’s husband. Mrs. Lashley, a few hours before the appointed time, sent for Boisseau. She had been told that he who would be carrying out the execution and she asked him questions regarding the details and was particularly anxious about any potential suffering. Affected by the conversation, Boisseau phoned governor McKinney in Richmond to inquire if there was any doubt at all about Mrs. Lashley’s guilt. The Governor assured him that the sentence had been declared and must be carried out.

“The art of hanging people…,” as Mr. Boisseau explained to the Bee in October of 1924 when he was interviewed upon the anniversary of his record-breaking 53 years of service, “was to kill quickly without mutilation of the body. Another prime requisite is the knotting of the noose and the ability to place it about the neck of the impending victim so that when the body has fallen the neck shall be broken and strangulation shall not ensue.”

The executions took place in a vacant space between the jail and courthouse, where a 25 foot plank fence was erected to prevent spectators. In most localities executions were a public spectacle, but Boisseau felt that the event should be private and solemn. The only spectators were twelve witnesses who were called to attend, selected similarly as jurors for a trial, and no fewer than two doctors.

In 1904, after the hanging of William Jones for murder, Mr. Boisseau appealed to the state to conduct private executions from the state prison in Richmond. A bill was drafted and eventually passed. It’s possible that the invention of the electric chair in 1907 provided the means and necessity to bring Boisseau’s bill into law. In 1908 municipal executions were banned and capital punishment was centralized.

Mr. Boisseau lived for many years at 867 Paxton Street with his wife, Susie Dean Wicks Boisseau of Kentucky. The couple had two daughters. Their first child, a son, died in infancy.

Mr. Boisseau maintained his position as city sergeant until his death in 1932 at 82 years of age. Harry Wooding lamented at the time that Mr. Boisseau was the last remaining city official occupying a post when he first became mayor of Danville. His 61 years of service set a record for any public servant at the time and probably since.

July 23, 2024

In the beginning…

No, not that beginning.

The other one. After the great burning. When God’s chosen vessel

came to take his rightful place upon the throne, ruling over all, at

long last, as He had promised.

But God works in mysterious ways, and that Utopia so many

had looked to with hope and anticipation, had yet to materialize. Such was the

fault of man who had not yet learned to trust with complete faith and with an

eye single to God’s glory.

The world was baptized once by water, and then, as foretold,

by fire.

And the phoenix rose with wings of flame and a golden halo.

After the wall was built.

After the refugees were expelled.

After supremacy of a pure race was reestablished.

After the alliance was broken.

After the planet was raped and plundered.

After the axis powers made that final assault.

We were left alone to be ruled by He who had come to save us all. Or so we believed …

Once upon a time.

July 22, 2024

I’m Still Here…

I have been quiet. I have been thinking. I have been grieving. Still. And trying to determine myself to some course of action that will render me once more purposeful and productive. And content.

The tenacity of this grief is an exhausting thing. It is a burden and a blessing. But more than anything, at least of late, it has been a preoccupation. I am treading water. Again. And my life is, month by month, week by week, day by day, passing me by.

I am fifty. Half way (more than half way, if I am honest with myself) between life and death. Do the first twenty years even count? I was a child. I was learning life, not living it. Not really. Not making decisions for my own about how I live and what I do and what my name should and would mean in the mouths of others. I’m fifty, and the losses that have seemingly paralyzed me over the last nine years are not the last I’ll experience. So why does my struggle seem so extraordinary? Is it? Or are we all walking around with these burdens and pretending we are fine? Is being an adult simply the day-to-day play acting as if we are too strong to feel or show or admit that our inner worlds are filled with lonesome suffering?

I recently read Carolyn Elliott’s Existential Kink. It’s premise is that the way to overcome many of our obstacles is not to try to avoid them, but to lean into them. By finding ways to take pleasure in the things we think we hate, we can overcome fears and roadblocks to our own progress. There are things in this life we can’t avoid: rejection, disappointment, fear, and shame. But leaning into those things teaches us precious lessons about ourselves. She spends a long time on shame, how shame warps our sense of self and actually makes the things we feel shameful about all the more tempting and exciting. Shame represses our secret desires and warps them into something that nags and pesters us in the moments we least expect.

There is a shame to grief, I’ve found. Having just passed the four year mark of my sister’s death, I feel an obligation to have “gotten over it” and to have moved on. I think about it less, certainly. But there is a resentment I feel toward that ever increasing distance between myself and her existence. In many ways I don’t want time to pass. In some respects I miss the newness of it, the feeling that she was just right there a minute ago. The acceptance that she is not coming back has well and truly set in. It is my reality now. I have moments when, after a long time of not having thought about it, the horror of it comes back to me. I have to work to put myself back in that place: waking up to missed phone (several of them) from the medical examiner’s office; the photos posted almost immediately by the news; the video posted to YouTube of flashing lights and broken glass, a dead dog, an overturned car … a body under a white sheet. Ambulances, and gurneys used and unused. How the driver, her husband, simply walked away. The witnesses, the lies, the pieces of conflicting information that don’t and never will add up. The answers we’ll never have. These are old news now, the shock of them worn dull and smooth, but heavy nonetheless.

In A Grief Observed, C.S. Lewis talks about the embarrassment his desire to speak of his wife caused in those who also loved her. In the introduction to that book, his stepson, Douglas H. Gresham clarifies that embarrassment as shame inherent in the emotion he would undoubtedly show in the course of such conversations. Boys don’t cry. People of a certain class, of a certain education (and certainly of a certain gender) are meant to keep it together, to maintain composure, to preserve that “stiff upper lip.” But he also speaks of the opportunities missed to speak of his mother, to share that grief, and in grieving, hold her close again, even if only in memory.

Karla McLaren in her book The Language of Emotion refers to grief as “the deep river of the soul” (which I ironically discovered in my sister’s library and which is a beloved and well-worn book in my own library now). In her section on grief she talks about the human tendency to avoid grief, but in that avoidance, “we make the tragic mistake, and each death and each loss, because we don’t feel it honestly, just stacks itself on top of the last death or loss…” She speaks of the importance of leaning into grief, of moving down into it. “The movement required in grief is downward,” she reminds us. “When you move through grief in an intentional and ritual-supported way, you’ll feel pain, but it won’t crush you; your heart will break open, but it won’t break apart. … If you let the river flow through you, your heart will not be emptied; it will be expanded, and you’ll have more capacity to love, and more room to breathe.” She speaks of the importance of rituals that can be relived (think Dia de los Muertos rather than funerals that are done and over and never revisited) because grief doesn’t simply stopped. I sometimes say I luxuriate in emotion when allowed to do so, but Ms. McLaren almost encourages such things when it comes to grief. To move through it, one must feel it. Like an Existential Kink, grief is not something to necessarily be enjoyed, but there is an exquisiteness to it that brings us back into communion, if only for a short time, with those we have lost.

But the desire to avoid this downward dive into the emotional deep is strong. As I have recently been reminded.

In April I lost a friend to suicide. I always thought that those who took their own lives must be insane. What does it take, after all, bypass the innate and primitive need to preserve one’s own life? But I never knew anyone more sane than her. She had planned it for some time. She was deliberate and detailed, even going so far as to plan her own funeral. It has been a devastatingly sad experience, coming at a time when I feel a keen scarcity of close friendships. She was quickly becoming my new best friend. But I arrived too late. She had warned me, in a joking manner (of course) that she was could relate very well to the Barbie who experienced “irrepressible thoughts of death”. Her exit strategy was already on her mind. She prepared her clients, she made sure all was in order at work and at home, and she made her exit, like someone walking into another room and closing the door behind her. Only the door disappeared when she did. Is it that easy just to leave? I have been devastated by the loss of her, and yet there is a sort of strange comfort in the notion that this was what she wanted. I see her, her arms spread out wide in frustration: “Guys! This is what I wanted!”

And what do I want? I want to live. I want to experience life, its ups and its downs, its lows and its highs. But boy am I ready for some highs. I want to fall in love. I want to travel. I want to have a book published traditionally and see it for sale, stacked high on a table at Barnes and Noble. I want to be old and to look back on my life and think, I’m so glad I did not fear living!

But I think … I think my fear of living is, as Carolyn Elliott suggests, nothing more than the heads side of a coin that is my fear of pain and loss on the other. I’m not going to get over my sorrow by avoiding grief, by avoiding all the experiences that might cause me disappointment or heartache. I’m going to have to lean into it. For me that means writing. And I am keenly aware that if I do not make a real effort to save my writing career, I’m going to lose it. So I will be harnessing my grief, harnessing my anger, and finally, at long last, moving ahead with some of my writing goals (more on that soon). Suffice it to say, I have several things I’m working on, and hopefully … hopefully, some publishing news soon.

Until then, thank you for sticking around and following me on this journey, even when (especially when) I need to delve into the deeps and feel a little sad.

Blessings!

(and more soon)

December 5, 2021

Good Grief, it’s Complicated! (On the nature of grief and sorrow.)

“Human experience often brings such a complexity of emotions. Not since I was a small child have I felt anything unalloyed, not joy or anger or sorrow. For as long as I can remember, and more especially of late, I have experienced little else but the overwhelm of emotions that gather in crowds of mixed company.” ~ Fearless

My father was never what I would call healthy. Strong, yes, but not healthy. There was never a time I can remember when he was not in pain of one kind or another.

It was in 2003 when his health took a serious turn for the worst. He was diagnosed with esophageal cancer which bears a survival rate of something like 12-16%. I was asked to come home then. Not by him, of course. He was too independent for that, and my stepmother, at that time, was well enough to care for him. It was my sister who wanted me near. She was an hour from him in good traffic, but she could take some time off of work to help him get to his appointments and to sit nearby on his worst days. And they did get bad. I had just had a baby, and so my ability to travel was somewhat limited. My father pulled through it, though perhaps just barely. The ordeal proved a trial for my sister, and I think she bore a lot of resentment toward me for having to go through it alone.

In 2009, his health suffered another set back when his heart began to fail. He woke up one mourning and just felt he was seriously unwell. He waited for my stepmom to wake, and then he had her take him to the hospital, where he was diagnosed with congestive heart failure. They put him on diuretics and made plans to have a pacemaker inserted.

And then came the heart attacks. Only that’s not what they were in actuality. His pacemaker was equipped with a defibrillator and for some reason, whether it was because it was set to respond too readily to the slightest irregularity or if there was some other cause (working with his arms raised or around electrical impulses) it went off on him two or three times. Each time he thought it was the end.

And so it was that on Christmas eve of 2009, my sister called me (drunk) to tell me I needed to come home or it would be too late, that my dad was going to die and if I didn’t come home, I would not have the chance to say goodbye.

But I didn’t go home. My husband had just taken a new job in another state and I was alone in South Carolina with three children and a house to prepare to put up for sale. I couldn’t leave. I had to take my chances that the end was not so nigh as she feared it to be.

Just a couple of months later, I got a phone call. “Are you sitting down?”

“Yes.” I had been sitting on the floor, actually, working out how to rewrite the book I was getting ready to publish (my first). There were papers spread all around me, pens and highlighters …

She bore me the grim news. But I was sure I hadn’t heard it right. I stood. “Will you repeat that? I don’t think I heard you.”

“Jeff died.”

It was a blow I was unprepared for. You know from the time you are old enough to conceive of such things, that you will eventually lose your parents. To lose a sibling, though, … That is not supposed to happen. Not so young. He was 46. I was 37.

“How? What happened?”

“He collapsed in his driveway and hit his head. He’d been working on his car, and maybe he stood up to soon. It’s not clear. He went inside and laid down on the sofa. He asked JoAnne to call 911, and by the time they got there, he was gone.”

He had just gotten out of rehab. He had been told, and quite plainly (from what we later read from his journals) that if he drank again, it would kill him. And it did. Yes, he’d been drinking.

For awhile I was angry. I didn’t really process the loss right away. I had to be strong. I had children to care for, and who was there to care for me? No one. Women are caregivers, not carereceivers. There is a red line under the word as I write this. Do you know why? The word doesn’t exist.

Lisa was territorial about her relationships. After Jeff’s death, he became her brother more than mine. I bottled up my emotions and refused to process them. I had a book to rewrite. I had a house to finish and to pack up. I had kids to take care of.

And then one evening, we were watching a movie, and at the very end was a trailer for another movie. The track that scored it was Keane’s Somewhere Only We Know. I don’t know why that song. It was just that it hit me by surprise, and yes, I love Keane, but there was no special meaning to the song that would assign it to my brother’s memory. It just played, and I fell apart. I sobbed loudly, covering my face with my shirt out of shame. My husband was with us that weekend, and, characteristic to him, he quietly left the room, unable to tolerate that kind of emotional display. The boys stared at me in concern and surprise. My eldest came and sat with me and held me close, and let me spend the emotion I’d been holding in.

I later told my sister about this, but she took exception to the idea that I had some “secret place” I shared with my brother. I assured her it wasn’t the lyrics of the song that did it for me. I think it was just the band itself, and the way the song had come on so unexpectedly. My brother and I listened to much of the same music, and it felt like a hello from him. It still does, but I can’t tell you how or why (except that I really do believe in such things, and there doesn’t need to be a reason beyond feeling that it is so). She later criticized the way I had grieved for him, before and after that time. It was none of her business, really. But maybe that was her way of taking out on me the anger she felt at those in our extended family who had told her it wasn’t really so bad … he wasn’t our real brother, after all. But he was. He was my father’s son, and I loved him.

My grief for my brother was relatively simple. For a time I was angry that he chose to drink and therefore to die. I was disappointed in him. He had done such a bad job processing his compound disappointments. In many ways he was like my father, though, an addict, yes, but also a tortured boy growing up into a tortured man. He had something my father didn’t, though: the love of a devoted and adoring mother. I think he would have had that, but he was orphaned at the age of four. His parents, the ones that gave him life, loved him. I know that. The ones who adopted him, well … they tried, I suppose, but it was the 40’s, and a man needed to be toughened up not coddled. And boy did those boys learn to be tough!

Once the anger subsided, there was only love. Jeff was nine years older than me. We had different mothers. He never lived in our house, and I was lucky if I saw him twice a year. But I had no bad memories of him. He was never unkind to me. He never called me names or bullied me. He was always loving, nurturing, and very, very funny. My regrets are these: I didn’t try hard enough to stay close to him as an adult, I didn’t give him the time I should have, and I was never the confidant I might have been to him. Could I have saved his life? Probably not. But I certainly could have done more. But that is the true nature of grief. Grief is the love that remains, when those we have loved have moved on.

In 2015, my father was diagnosed with stomach cancer. I was at last in a position to help out. My marriage was ending, I was in the middle of an infatuation that was moving toward an affair if I didn’t do something drastic, and my father was dying. There was only one thing I could do. I could go to him. My stepmother had been diagnosed with dementia a few years before, and she was in no position to care for him. Not then. I could go. I wanted to go. And my father wanted me there, as well, another indication of how serious the matter was.

I won’t go into detail here about what that was like to be in Washington where I grew up and to care for him and for my stepmother as well, as that story will require several blog posts on its own. I was there for seven months. During that time, I got divorced, I ended and rekindled and ended again my relationship with my long-distance paramour–and learned things in the interim about myself and about him and my relationship habits that I have spent the last nearly seven years trying to resolve and amend. And I watched my father grow very, very ill and then, miraculously, recover. During that time I got to repair years of resentment and misunderstanding between my father and myself, and I got to spend some much needed time with my cousin and with my sister. But again, it was complicated.

Lisa resented my being there. She felt I had encroached on her territory. Everything I did was open to criticism, from what I did in my spare time to how much time I spent on my computer. I was still trying to write. It was and still is my best outlet and the thing that brings me the most peace. But I was also trying to learn about my self at that time. I was doing a lot of what my stepmom called “studying” reading every relationship book I could find, every “fix yourself” program I knew of. I was hurting and I wanted it to stop and, most of all, I never wanted to feel like that again.

In 2017, the cancer came back, and this time it was terminal. My father said goodbye to me over the phone. I remember sitting on the edge of the bathtub, locked in my one and only bathroom, and trying not to cry until I got off the phone. He had days. He was about to be put on palliative care–morphine–and would not be lucid again.

He lingered for almost a week, while my sister and my stepmother sat beside him. But neither of them handles stress or grief well, and they were at each other’s throats. My dad had asked me not to come. He didn’t want the trouble. He didn’t want the hassle. He just wanted to pass in peace and quiet. But after several days of sleepless nights and missed work, my stepmom and my sister said their goodbyes and left him. But neither did they want him to die alone. I got on a plane and arrived at the UW medical center at 10:30 pm. He was wasted and waxen … and old. He was 79, but he looked much older. Or perhaps, for the first time, I finally saw him as the spent man that he was. He had fought so hard, had battled seemingly insurmountable odds so many times. It was hard to accept that this was it.

I took my seat beside him. I said a prayer and sat down to meditate, but I didn’t speak to him. I was a little afraid of his knowing I was there. He had asked me not to come, after all. But when the nurse came in and asked me who I was, I told him that I was the daughter, come from Virginia, to take care of everything.

Four hours later, he slipped away quietly.

For as villainized as I was for making that decision to leave my family in Virginia to go to Washington and take care of my father, I have never once regretted the time I got to spend with him, the opportunity I had to make peace with him. I loved him, but our relationship was complicated. He wasn’t a very good father, and I often wondered if my brother resented us at all for his leaving him to start a new family with us. Jeff had it far worse, I know. If he did resent it, it never showed. My father had good qualities, too. He could be generous. And he was immensely talented. He was a gunsmith, a woodworker, a cook, a writer, and an artist. He could build anything, and he loved to learn new things.

My father’s death had an immense impact on my relationship with my sister. I spent a lot of time after his death not speaking to her. She felt wronged in so many ways. I got too much of his stuff after he died, I was there but not there, somehow. She liked to say “you never lived with him, so you don’t know.” Except I had lived with him, for seven months. She had spent the occasional night there after he married my stepmom, but she had never lived with him, so it made no sense. I feel like maybe it was something she needed to believe. She would also say “we helped him so much” during that time, but she was working. I don’t resent that, it was my turn, but … I was the one who did all the driving, the shopping, the medicating, the cleaning up. It was such a strange narrative she needed to maintain, that she was somehow more important in the scope of his life than even my stepmother was to him. It just wasn’t true, but in her mind it was irrefutable.

In the months just prior to her death, we had not been speaking. I had just had enough of the constant berating, the picking fights, the gaslighting and narcissism. I couldn’t do it anymore. I was learning (and still am) how to establish and maintain healthy boundaries for my own peace of mind, and so I had cut her off. But then, right around her birthday, she had gone in for emergency gallbladder surgery. I called her to see how she was doing. We talked a little, but she made it clear she was not ready to consider us friends again. Just a week before her death, we had begun texting. She was excited to start a new job, a job she would never show up to. It all ended so suddenly, so unexpectedly. We had JUST been talking! She had just been there a moment ago, and then … nothing but silence.

Silence.

And that is exactly what it feels like. She is there, but silent. Gone but not gone.

And it’s complicated. I’m angry. I’m angry she left so soon. I’m angry that we will never have the opportunity to be what we always should have been to each other–best friends. I’m angry that she lived a life of self-harm and blame and not taking the responsibility for her own problems. I’m angry at the constant criticism and judgment. I’m just angry. So angry. I’m angry that her husband has shut us out of his life, though I don’t blame him. I’m angry that it must now go to trial. There can be no closure, but neither do I want retribution. Her husband has suffered enough for the mistake he made that night which led to her death. There was no intention to do harm behind it, simply a lapse in judgment. Most of all, I just miss her. And I feel so, so alone.

I sometimes wonder if life is just an experience of subtraction. That we are meant to live amongst this crowd of loved ones and strangers, until we have said goodbye to every friend who has gone their own way and to every loved one that passes on before us.

Life is so quiet now. There is no one to tell me what a bad person I am, or how I am a bad friend, or a bad sister, or a bad daughter. I suppose that’s something to be grateful for. But mostly, I’m grateful to have loved, even when it was hard, or complicated, or painful. I have loved, and that is a gift.

November 1, 2021

Ellipses…

In my mind, we were in the middle of a conversation. That isn’t exactly how it was. She had told me she had some things she needed to get done. She was starting a new job in the morning, and she was really excited, but it was important she was feeling good and was prepared and well rested for her first day. She would go to bed early. Her regular bedtime was around 8.

So why she was out on the road at 9:30, I cannot figure out. She had wanted to show her husband her new place of work … that was what he told us later. But why then? Why at night when it was growing dark? Had she gone to bed and found she couldn’t sleep and so, maybe, thought an evening drive would help her relax? She sometimes took sleeping pills. They sometimes didn’t kick in right away. He sometimes took pills, too. He sometimes didn’t tell her.

Whatever it was that took them out that night, whether it was a leisurely pleasure drive to see her new place of employment or a quick trip to the store, they would not return for many hours. In fact, she would not return at all.

Where their drive took them, it is impossible to say. Perhaps he was telling the truth and they had gone to see where she would be starting work the next morning, but the medical office where she had been hired as a biller was located twenty miles to the southeast. The car came to rest, on its hood, a mile north of their house on the shoulder of a busy stretch of urban roadway.

There’s so much we don’t know and likely never will. What we do know is that the car was stopped for approximately ten minutes at an intersection just prior to the accident. A witness came upon it their Volkswagon from a different direction at a four-way stop. They waited for the car to turn or to drive on, but it just sat there. The witness went on to the store. Upon returning, the car was there still. Inside was a man—the driver—apparently asleep, a passenger who could not be seen clearly from the way they were slouched in the seat, and a dog. The witness sounded their horn, and the driver woke up and proceeded onward. Perhaps he had meant to turn there. Perhaps he fell asleep and, upon waking, forgot where he was or where he was supposed to be going. There was no mention of a signal. It was clear, however, to those observing the car, that the driver was not in a state to be driving. His speeds varied, sometimes well below the speed limit, sometimes significantly over. He weaved all over the road, occasionally crossing the middle line entirely. At one point he swerved off the road and struck something and then, correcting himself, continued onward, while the dog who rode as passenger—Charlie—ran from side to side and appeared to be trying to get out of one of the windows which was rolled down.

At the only point for miles where the road significantly turns, an oncoming car came into view. The driver swerved back into his own lane and, overcorrecting, drove onto the shoulder.

I can only assume the Passat was not the first car to have struck the mailbox that sat in front of the house situated on that curve of Waller Road. Between the house and the road, placed there, I imagine, to ensure that no car could intentionally or unintentionally knock the mailbox over, a pile of large landscaping rocks (the size you would use for a border, perhaps 12″ in diameter and irregularly shaped) were arranged around it and piled high. On the north side of the mailbox was a tree stump that might have been found as driftwood on a beach. It was not fixed, not part of a tree that had grown there, but found and given the dual purpose of decorating and protecting this artificial island where a mailbox stood.

I will say this, and I will say it again: Phone calls in the middle of the night are never good news.

“There was a car accident, and Lisa didn’t make it.”

Those were the words my mother heard when she answered the phone at 1:30 am. I would wake several hours later to find a multitude of messages, missed phone calls, and voicemails.