Stephen Orr's Blog

December 7, 2025

In Search of Joyce (and others)

Six weeks walking, studying maps, hobbling on my dodgy foot, all to make one discovery. But that can wait.

It starts in Dublin. The James Joyce walking tour. Along North George’s Street, framed by Belvedere College S.J., where Joyce first learned there is ‘no philosophy so abhorrent to the church as a human being.’ Yes, the Jesuits were fearful, but tempered. As I imagine the young man walking to school, settling in his room, waiting for a dose of Homer, already turning Dedalus in the cold morning air. Cold. Dublin is Liffey-chilled, eye-watering and seagull-squawking. The post office, with its bullet holes, ready to celebrate a century of defiance, although the greatest travesty now is the row of tourist buses parked across the street.

More Joyce! Come on, ladies and gentlemen, keep up, please! As we brave few (including the inevitable Americans, telling us how important Joyce was to their Idaho-childhoods) lean into the wind, imagine the great boy, teenager, young man, trawling these streets for material. We avoid Parnell Square (the old Rotunda Hospital where JJ was born) and head down Frederick Street North (with its peeling apartments, cheap hotels and off licence) to Hardwicke Street. The guide points to what was once the Joyce family home at number 29 (now a block of council flats), and we all try to imagine (but for my part can’t) John, Mary, Stanislaus and little Jimmy heading out for the day, perhaps to the nearby St Mary’s Pro-Cathedral (unlikely). And across there, our guide says, indicating a sagging little Victorian walk-up, you can see the building that inspired ‘The Boarding House’ (written in Trieste in 1905). In Joyce’s day, number 4 was a brothel, (as an Indian man and his wife come out with their several children). Joyce probably spent hours watching the goings and comings. Imagining the lodger, Bob Doran, forced into marrying Polly Mooney, the madam’s daughter (as it still goes on to this day).

Then a couple of teenagers on a loud, penny-sized motor bike start riding up and down Hardwicke Street, past us, closer and closer, grinning, as I recognise this Irish streak. We few foreigners (clutching our annotated editions) seem strangely out of place with the grog shops and Pakistani delis, flats, everywhere, and a few teenage mums with almost teenage kids. And I think, At last, Joyce’s Dublin!

Which brings me to the discovery. Although this early in the trip, I had no idea what I was seeking. Some Adelaidean Leopold celebrating his Orrday (after so many years of dreaming about it). As the stinking dung heap of a feeling began (destined to pursue me throughout my European odyssey): Am I disappointed? Is this what I expected (what was I expecting?)? I thought Dublin would be so…literary, but there are actual people, in trackies, bum cracks, a Subway, Starbucks. And the feeling: Joyce is long gone. He wasn’t even here when he wrote about the place; he hated it. Said, ‘When I die, Dublin will be written in my heart.’ But this Dublin?

No time for thinking. This way please. As the motorcyclists give up, head towards St George’s Church, and the next group of suckers. We continue, heads down, towards the Liffey. Stop outside the Gresham Hotel. By now, my dodgy foot is failing, and I wonder if I should slip away from the group, find a café, and seek Dublin through my own copy of Dubliners. Is that done? Can you just go? Roy and Shirley (Idaho) are monopolising the guide, so… But I stay, and hear about Gabriel and Gretta Conroy (upstairs, staring down across O’Connell Street Upper), Gretta ignoring Gabriel’s lusty hints, telling him about a long-dead lover who’d gone out in the rain to meet her (‘I think he died for me, she answered’). Gabriel’s interest flags, depressed that his wife (on their big night at the Gresham) still longs for Michael Furey. Then, he senses, we are all still living with the dead, and past. Maybe that’s my problem, attempting to animate a dead writer, falling asleep as cold Dublin loses its eternal friskiness.

The next day I try again. Jonathon Swift. Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, a few minutes’ walk from Temple Bar. I’d re-read Gulliver’s Travels. Studied his biography. Got to know him through his pamphlets (‘A Modest Proposal’, in which he explains how ‘a young, healthy child, well nursed, is, at a year old, a most delicious, nourishing and wholesome food; whether stewed, roasted, baked or boiled, and I make no doubt, that it will equally serve in a fricassee…’). Swift is still giving his sermons. Sarcasm, satire. But a love of humanity, and desire to see people at their best. Even now he can still piss people off (especially those who take him literally).

I spend an hour searching for Swift. In the park beside the cathedral where St Patrick used to covert heathens. In the gift shop, the post-Norman toilet (one of the few in Europe where you don’t have to pay-to-piddle), the North aisle and transept, the graves of Swift and his muse, Esther Johnson (Stella), Swift’s death mask, a selection of his writings (liturgical, and funnier) and his pulpit. As I sit and try to hear him. What sort of voice? Was he funny? Was anyone even listening (refer to his sermon, ‘On Sleeping in Church’)? My little voice is still asking, Where is he? Where are the Lilliputians? The flying island and smart horses?

Enough of this nonsense. London will cure it. A brisk walk through Bloomsbury. Like a dinosaur down Holborn Road, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Chancery Lane, Fleet Street, Gray’s Inn Road, Doughty Street. 48. Enter and leave through the gift shop (as usual). Into Dickens’ hallway, narrow neat, his front room, and he’s sitting there, planning the next instalment of Oliver Twist. Consulting ‘Phiz’ about the illustrations. John Forster’s just arrived, chatting with Kate Dickens, sewing, reading, taking tea, perhaps, in the small room at the back. Up the stairs to the great man’s study. The walls lined with bookcases, the desk, the writing table where Mr Bumble, Bill Sikes, Nicholas Nickleby and a dozen other characters daily came to life. This is more like it. The small of old paper, leather. The ghosts. Although, if you stop and listen, you can hear delivery vans outside, a helicopter, voices from the gift shop. So, where is Dickens? In his bedroom? I check, but there are just more fans, like me, searching for the keys to creativity, although they can’t be found.

And so it continues. Edinburgh. Conan Doyle at medical school (although his birthplace was torn down to make way for a roundabout and public toilet), Robert Louise Stevenson, learning the art of ‘illustrating death’ as he walks from Claxton Hill to Parliament Square, where you ‘strike upon a room…crowded with productions from bygone criminal classes…poisoned organs in a jar, a door with a shot hole through the panel, behind which a man fell dead…’ In Edinburgh, a thousand fireplaces have turned the sandstone black; the closes still musty, Black Death between the stones, in the foundations and daubed walls. Here, it isn’t the writers as much as the place itself. A city of stories. Rowling scribbling in her café, Robbie Burns drinking a kindness cup from the high ground as the pipers pipe and Dr Jekyll prows the streets, still.

On and on. The voice persists, the feeling. That we populate stories with our own meaning, and those who love storytelling the most, surrender to the illusion most completely. I continue to Berlin, but don’t find Brecht at home (or in the small, monastic bedroom where he died). There are clues: the rooms he didn’t share (due to his adulteries) with his wife, Helene Weigel. She was much more comfortable downstairs in her moo-cow kitchen, her glassed-in garden room, although they’re together again, in the Dorotheenstadt cemetery, a few metres walk form their old digs. Similarly, TS Eliot isn’t waiting out front of Faber and Faber, or smoking in Russell Square, contemplating the Heaviside layer. That’s still there, keeping radio waves in the atmosphere, stories in the streets where they were set, bouncing Sam Weller beyond distant horizons. Hooking people like me, who come looking, full of hopes.

As, eventually, the voice fades. You give up. You no longer care about Wilde’s house, or where he might’ve walked in Merrion Square. The stories are in the mind, the words, the pages, the books that remain. You can go all the way to Hamnavoe to find George Brown, but you might as well visit the local library, let the poetry propagate in your own ether. Joyce left Dublin in 1904. He once said, ‘One of the things I could never get accustomed to in my youth was the difference I found between life and literature.’ Perhaps that’s the key. Between the living and dead, real and imagined, the writer and reader.

October 25, 2025

Tallangatta

Before I start writing I hear the story of four boys who have died in the United States, fallen through river ice, cardiac arrest; and a neuroscientist facing his own mortality, two or three days before the cancer he understands so well (at the genetic, the cellular level) carries him off on the Great Adventure; the fear of losing loved ones, daily, hanging over our heads, the realisation time has nothing to do with you – you’re part of it, in it, but it continues despite any understanding, intuition, feelings of love, desire, empathy – sits waiting, and why should you be any different to the forty people who stood in your place before this moment? Once understood, and accepted, everything follows. A cloud seeded with everyone who’s ever lived, falling through time’s long ruin, gathered in some mystical, mythical place full of weeping grass and bluebells. If that’s how we want to imagine it, and why not? The idea that there’s no thought you’ve had that hasn’t been had; no frustration, no contempt, no desire, no shame that had to be hidden in the deepest, safest part of your brainbox. No poem that hasn’t been written, combination of notes making songs sung on cold, windy Burren days thousands of years ago; no insights into others’ behaviour, no overlooked solutions. You, simply, have been thrown into an unwinnable football match, probably because of a lack of players, destined to chase a small, soggy ball.

I think of the piece I thought of writing, describing the small town of Tallangatta. The town that was. On the day I visit, old Tallangatta sits under gigalitres of water, thirty, forty metres down, the main street all sludge, the Soldiers’ Memorial Hall and Free Library, Pink Bros. General Merchants, the billy buttons and club rush, drowned, in the name of 1950s progress. The coffee palace and cordial factory; the lusty, Methodist church and pig sale yard. And what of this place I can’t see, but stand at the end of Martha’s Lane imagining? The water lapping at my feet, inviting me to wade in, explore, some Tourism Victoria Experience sold to city folk, and here I am, disappointed. Think of yesterday, of this town, the four boys, the flooded graveyard, the long-abandoned six o’clock swill at the Victoria Hotel, Jock Cavanagh explaining how, as a boy, he and his mates crawled under the jacked-up weatherboard houses (to be moved a few miles down the road) looking for pennies and pounds and marbles. Spent his summer fishing for redfin in Tallangatta Creek, and now there’s no creek, no town, nothing but the Hume Weir and a body of water the size of seven Sydney Harbours, a safe, dependable supply of irrigation water that came at the cost of a small, Australian town.

This, then, is the old town, the town of Tallangatta, an Australian Brigadoon that only emerges in drought years. In the form of a few houses left behind at the time of the government relocation (1952-1954) because they’d been built on high ground (the ‘Toorak’ of Tallangatta). The butter factory with its rusted roof, its yard overgrown with river mint and pigface, old machinery and an abandoned car, the memory of milk, churn, butter, bread, Jock at the dinner table and Pappa says dear Lord, thank you for what you’ve given us, but soon their house, minus its outdoor dunny and rows of carrots and tomatoes and its toolshed full of rusted hammers and nails and the spot where Bob emptied the dripping from the roast and the bough-hung swings, floating beside Aunty Noreen’s bleached bones, windows in the school house where kids stared out at clouds (their Pythagorean ghosts marvelling at carp and cod), all jacked up and de-stumped, loaded onto the back of a truck and taken to the ‘new town’ (the old town of Bolga) a few miles away, placed on a numbered site ready to start again.

Post-World War I, the need for reliable irrigation water, the use of the Returned to build the Hume Weir, an engineering feat that, to this day, impresses. Water to the horizon, speed boats and catamarans playing in the silver-tipped waves, then heavy, prolonged rains, the weir gates opening, the bloated Murray flooding. But even then, it was obvious the weir could hold more, promise greater wealth, alluvial plains and beets and lettuces and fat angus and shorthorns to feed the Commonwealth. And already, by the 1930s, a discussion about increasing the weir’s capacity. Problem being, Tallangatta, built in the bottom of a low-lying valley, the annual floods, the winter fogs that lasted until one in the afternoon, this unremarkable town that had started off as a series of cattle runs in the 1830s, an 1854 foundation-stone, the Indigenous name Tallangatta (‘place of many trees’) borrowed from the local Pallanganmiddang and Dhudhuroa people. And from the outset, there were concerns. The usual drought and fires, but mostly the annual floods, so bad the council built a shed to store boats so people could get up and down the main street after heavy rains. The horses were used to getting around girth-deep in the mud. This, everyone agreed, was what came from building in a valley.

I stop beside the highway, look across the flooded valley, read the sign saying this is where Tallangatta used to be. A feat of imagination, although an old bridge still exists, taking the ghosts from nowhere to somewhere – wedding, funerals and wakes for Clarry and Eunice, Bown’s main street Draper, chiffon curtains and a doily for Edna’s phonograph. Once – down deep in this submarine city, this wattle-and-daub Atlantis, a thousand miles from the closest coast – you could visit T.J. Brazill, baker, for a cob loaf, sound the fire alarm if you saw or smelt smoke. Now, just double-glazed visions of the past and the memories we grant it, the names we choose to remember, a glossy, brochure-perfect landscape with bald hills (cleared for firewood, willows for stock in drought years) and sheoaks on the high ground, river reds with their feet in the liminal zone, drinking the murky water in wet years, storing it for the dry, yam daisy and native lilies and an old pre-flood oak surviving beside one of the few houses left in ‘Toorak’ (the wealthy of the Australian regions always built their homes near the hospital on the high ground, anticipating the vagaries of climate, and history).

A road crew in a truck pull up and park in the lookout, search their phones for messages, sit in the cab and eat sandwiches. Meanwhile, the ghosts are busy – the wind working at a chocolate wrapper caught in the wire fence (although the Kit Kat isn’t going anywhere); a warm day, the frustrations and desires of the old townfolk almost audible through the needles of a nearby pine. As I read the usual interpretive panels, fading, just like the memory of whatever happened below these waters seventy years ago. Friday night, the men from H. H. Goodwin filling the pub for six o’ clock swill, their kids waiting outside, lemon squash and bikes made from bits and pieces of older bikes, and older bikes, this churn of life, of love, of routine like it always had been, and would be, amen.

Four boys dead, but only two fell through the ice, and the others went to save them. Like, in numbers, things would be better, like whatever happened in the world that day happened here, whatever thoughts and feelings and pain and horror as they reached for the surface, for the sun, for the voices above them. But our capacity, as a species, for moving on, is enormous. Like the living and the dead have an understanding, and anyone who can hear the old people calling can hear what they’re calling.

After the town was moved – lines on a map, lots drawn, sewers laid, gardens planted, concrete footpaths – there was a sense of unease: that, for all its newness, its water tanks and reliable electricity, this place didn’t add up to what they’d left. Still, these were tough, reliable people, used to hard times, wars, nothing phased them, except perhaps a loss of history and belonging, lives dislocated in much the same way as the local Aboriginal people. Something about roots, lifting a house on the back of a truck and taking it elsewhere, temporary nomads demolishing red-brick pubs and shops and replacing them with neat, asbestos-trimmed laundromats and shire halls. No more fishing or swimming in the river; no more selling mushrooms to the Myrtle Café (‘Three Course Meal a Specialty’). With the end of the old town came the stripping away, the loss of old connections, of shops with a house out back, smoked sausages and pickled onions in clay pots, the day Mary Fraser locked the visiting magistrate in his hotel room; the Oddfellows used for art displays, reading circles, crocheted rugs as a way of dealing with the loss of sons in the Great War.

I couldn’t have come at a worst time: the tail-end of a wet winter dragging its arse into October, November, December. The Hume was up, no signs of old Tallangatta. So I stopped my car short of the submerged town, walked to the water’s edge, and listened. Nothing except a striped skink on a rock, fat exhausts from motorbikes on the highway – steamy days, the walk to town (no one could afford a car), sleep-outs full of stray uncles who spent their days listening to the races. But the new place would be just as good, better. It’d all be done properly – everything surveyed, paid for, and if you didn’t get your first choice, then your second, your third. Of course, the usual claims of favouritism, committees stacked with local businessmen, who got the best shop on the main street? A hundred houses lifted between 1954 and 1956, 37 new homes, birches and elms planted in civic parks to replace swamp paperbarks and tea-tree that’d lined the river for millennia. Dunnarts and bandicoots replaced with Jack Russels and cats, Aboriginal songlines with Leave it to Beaver (fine-tuned in the after-school haze, blue gum skies full of smoke from stubble burns), bent-wing bats with budgerigars, sugar gliders with rats and rabbits and fallow deer introduced by well-meaning Acclimatisation Societies. Change the only certainty. Television ads for labour-saving devices promised a more civilised existence. A machine to dry your clothes. A Holden. A petrol station to ensure you were never stranded.

One day I’ll go back to old Tallangatta. I’ll wait for a long drought. For the waters to recede and the streets to emerge. I’ll walk the main strip; I’ll stop in front of the Victoria Hotel and listen to the voices in the front bar, kids calling for dad to come home, mum wants you, she’s pretty pissed off. Jock will be there, eight years old, and the Grade six kid his mother gave two shillings a week to dinky him to school. A bank, the manager with poppy oil in his hair, who’ll know the name of everyone’s kids. The cinema that started with Fred Astaire and finished with James Dean, the popcorn, the worn carpet along the aisles. I’ll listen to the conversations about the new maths teacher and Harry’s bulging disk and the rumours the government wants to move us all, but they’ll carry me out in a box before that. On a cold morning, the boys running down to the creek, and in they go, and this gyre, this churn, this cycle continuing until the next rains, more water and we’ll wait another thirty years to remember who we were, and are. But we’ll hear the voices calling; listen, and make out what they say, and realise they know our names.

September 25, 2025

Stasi-Day

Berlin works on many levels. Artsy, kinky, sombre, depressing, the excellence of the Berlin Philharmonic and its 1963 modernist hall, a coffee and film at the Sony Center before a stroll in the Tiergarten. A cruise along the Spree, every street corner heavy with history, the Weidendammer Bridge and its role in the last days of the Reich, Museum Island. History, everywhere. A country that wasn’t allowed to get on with life after May 1945. Leading us back to the museum of the German Democratic (by name only) Republic. Here, lives laid bare. A people told to ‘be happy and sing’: a generation of kids taping songs off DR-64, watching Western television (the signals couldn’t be blocked). Pioneer afternoons collecting scrap for the State, or listening to bands such as the Puhdys or Karat. Monday morning assembly under the red flag, a senior student proclaiming, ‘Comrade Principal, the school is assembled!’

Heady days. As long as you kept your mouth shut. And it’s still there, mostly. The fascination with East Germany and Berlin has never been greater. Any visit to the capital can be a learning experience. Before you go, grab a copy of the German Book Prize winner In Times of Fading Light, by Eugen Ruge. Here, in one novel, a plotted history, a re-imagining of the second half (nearly) of the twentieth century in the East. A son’s coming-to-terms with his parents’ ‘glorious’ past. But the fascination extends beyond this. Deutschland 83, The Lives of Others, Goodbye, Lenin! Matt Damon visited in The Bourne Supremacy, although the classic post-war German film is Roberto Rossellini’s 1948 Germany Year Zero, a haunting vision of Berlin in ruins. The dark side of this great city that fascinates so many. Maybe it has something to do with the angst of our own age? The worries about political power, privacy, a population’s acquiescence and willingness to accept uncomfortable orthodoxies.

Mostly, Germans don’t mind discussing the past, although when the Berliner Unterwelten tours began twenty years ago, the society’s critics accused them of glorifying Nazism. I had the pleasure of exploring the Friedrichshain flak tower, a few kilometres north-east of the city. Here, a fortified defence (four 12.8 cm guns) the size of small skyscraper, now half reduced to rubble, where you can put on a hard hat and experience the darkest, coldest, most miserable moments of the lives of other (Berliners) in the dying days of Hitler’s war. Where you can imagine Soviet tanks pounding the walls (barely dented).

Life in the East wasn’t all bad. Free education, a nice flat in a prefabricated WBS 70 tower block, a Diamant bicycle, or a packet of Juwel cigarettes to smoke after school. Plenty to choose from, although whether you could actually buy anything? One story has book dealers gathering once a week to place their orders. Twenty thousand copies, perhaps, of a new Christa Wolf or Stefan Heym book. And of this, the shop might receive twenty copies, ten, or five – just enough for the employees. A planned economy without a plan, and like the best of them, favours for the inner party.

The other hallmark of the East, of course, was the management of public opinion, and dissent.

House 1. Sounds ominous, and it was. This was the first of many buildings owned and operated by the Ministry of State Security (Stasi, or MfS). A fifteen-minute ride on the U5 from Alex. A collection of soulless structures that tried their best to disguise their purpose. That is, watching you. The three pm English language tour, as our guide showed us through the offices of Erich Mielke, the Minister for State Security from 1957 until the GDR collapsed under its own weight (and debt) in 1990 (the fate, I guess, of even the most ruthless dictatorships). Here, the wood veneer lifting in the foyer, the statues of Marx and Lenin a reminder of a dictatorship at its muscle-flexing, life-destroying best. The model of the dozens of ‘houses’, once full of eager servants of the state. Mielke’s suite of rooms: his wood-panelled office looking out across this workers’ paradise, the conference room, with its blue-backed seats and table for discussing politics, people, ideology. A small television for monitoring the media, a bed (he put in long hours, his devotion to Communism beyond question). And in the other ‘houses’, tens of thousands of Stasi agents monitoring people’s privacy – phone calls, letters, administering the 189,000 informants on the books (so many, that the German reunification could only proceed with a general amnesty).

There was a country, but mainly, a party. The Socialist Unity Party (SED) was East Germany. The party’s official hymn explained that ‘The Party, the Party, the Party is always right!’ Enough of this drummed into you from an early age (Hitler had recently done the same thing with the Hitler Jugend) and you might actually believe the lies. After Stalin was put out to pasture in 1956 (his name no longer mentioned), and Walter Ulbricht ‘retired’ by Leonid Brezhnev in 1971, new leader Erich Honecker set the tone. No more I, only We.

The following day, Hohenschӧnhausen, and the Stasi prison (Gedenkstätte). For forty-four years this clutter of buildings (eerily missing from maps) was the unspoken endgame of any dissent in, firstly, the post-war Soviet Occupation Zone (Special Camp Number 3), and later, the GDR. This time a tram trip through east Berlin, mounds of the old city still waiting to be cleared, the same dreary apartment blocks mixed with trendy cafes, parks and galleries. This was where the Stasi (‘the sword and shield of the party’) and its 91,000 fulltime employees dealt with the recalcitrant. Seventeen prisons in all, although this was the biggest. Its original red-brick block still in mint condition, the grounds, sheds, outbuildings that were once home to as many as 4,200 inmates. Overcrowding, disease, dead bodies dumped in old bomb craters.

At the start, there was the ‘U-Boot’, damp, cold subterranean cells with a bed and bucket, lights burning all day and night, sleep deprivation, physical torture, comrades made to stand in the one spot, sometimes in semi-flooded ‘water cells’. Then, at night, taken away for interrogation.

This, I thought, was (and is) the end of free speech. The dilemma Orwell warned us about. If any of your ‘incorrect’ letters were intercepted, if a contrary opinion was expressed in the lunchroom. A few agents planting bugs in your apartment, gathering evidence, then, a week or so later, a knock on the door at three in the morning, downstairs into an innocuous-looking ice cream van, a two- or three-hour drive to disorientate you, allow your fear to simmer. Then, the Gedenkstätte, a small arrivals hall in the efficiently named New Building (1960), bright lights to increase your anxiety, into an office to be ‘processed’, wiped down with a rag in case the dogs ever needed to track you, personal details given up and paperwork completed.

This repeating, night after night, as your interrogator warms to you, offers you cigarettes, tells you not to be alarmed, and you, trusting him, sleep deprived, start talking. He says it’s okay, it’s just you and him, and turns off the tape recorder, but of course there’s another one hidden in the cupboard. He asks why you said such silly things about the Party, because you did, didn’t you? And in the end, you agree to anything. Yes, I did.

The funny thing being, after a day at House 1, and another at the SdF prison, none of this seemed so strange. Like Mielke could’ve been my uncle, and I was here, visiting him at his office. Like the New Building was sort of okay, comfortable, warm. And these interrogators, surely they were decent people, deep down? There were even photos of their Christmas parties, dressed up as the people they arrested. And if all this seemed so normal after a few days, what about weeks, months, years?

When the gates of the Gedenkstätte were thrown open in 1990, hundreds, thousands of stories of broken families, betrayal and misplaced faith in authority emerged. One that struck me was of a son who was given his file and discovered his father had betrayed him to the Stasi. I was left wondering what sort of society Honecker had helped mould. So many East Germans had been motivated by their hate of the Nazis, and their persecution at fascist hands, but it was strange to think they’d just continued the tradition, albeit in a different form. Maybe, I guessed, they didn’t recognise the similarities, or maybe they thought the end would justify the means? Maybe this was the lesson of my visit? How quickly things can change. In our own age of (lack of) privacy, monitored internet and phone calls, closed-circuit television, limits to free speech. Maybe we all need to revisit the past to see (a possible) version of the future. As our own governments replace common sense with taxpayer funded propaganda. Or maybe it’s just the smell of a place? The damp in the walls of the water cells. Or the way voices continue echoing off the polished floors.

September 18, 2025

Blütsbruder

You know the feeling. A book you’ve been wanting to read for ages, you’re halfway through, loving it, dreading the end (not the ending), when you’ll have to leave this better-than-reality world. Like many readers, I have phases. I’m in the middle of a first-half-of-the-twentieth-century author phase, starting with Hans Fallada (starting with Nightmare in Berlin), Alfred Dӧblin’s experimental Berlin Alexanderplatz, progressing through Robert Walser (especially his mysterious microgrammes), Joseph Roth and Stefan Zweig. A group of authors connected by a strange sort of misfortune – a lack of success, mental illness, grog, Hitler and Goebbels, a country in the process of renouncing a thousand (or more) years of culture in favour of autobahns and stadia (sound familiar?). And then I heard about Haffner, and his fortunate, unfortunate, life. The discovery of another gem, lost, rediscovered, sifted from the ashes of Bebel Platz (compare this with Barbara Cartland’s 723 literary turds and you’re left wondering if there’s any karma in the universe). Ernst Haffner’s 1932 Blütsbruder, a novel about a group of outcast youth living in interwar Berlin, petty crime and prostitution, trying almost anything to get by.

The eight boys … spent the whole endless winter’s night on the street. As so many times before: homeless. Always trudging on, always on the go ... Two have parents somewhere in Germany. The odd one perhaps still has a father or mother someplace … From the moment they undertook their first uncertain steps, they were on their own.

A short, taut, no-nonsense book set in the ale-smelling, drum-thumping shadows of the German capital, each of the boys free to roam, but isolated in their patch of city. Ludwig and Willi, trawling the length of Tauentzienstraβe, the bright lights leading towards Kurfürstendamm, as they feel

… they are in a foreign city. What’s Berlin? As far as they were concerned Berlin was Münzstraβe and Schlesischer Bahnhof. It never occurred to them to go to the west of the city.

As with Hans Fallada’s Little Man, What Now? (published the same year), Berlin is the star of Blütsbruder. None of the rubble and grim desperation of Rossellini’s Germany, Year Zero (yet), but the decadence of well-to-do Berliners (Haffner called them ‘the amusement mob’) living in a city that had cleaved along the planes of braised ox cheek at the Hotel Adlon, and the seedy back alleys of Mitte. A world that Haffner knew well in his day job as a social worker and journalist. But he wasn’t interested in Isherwood’s Sally Bowles, or Josephine Baker’s moves at the Theater des Westens. His was a glorious darkness, and the result – all short sentences and half-edited paragraphs, the mumblings of these dirty boys and their bad attitudes, the street-talk Haffner adopted as his own – is a sort of historical document more powerful than any newsreel or –paper.

At noon, Willi and Ludwig are woken by the sound of a plangent voice at the door … Gradually it dawns on the boys where they are. In the white sheets of a private hotel. The distinguished gentlemen left after a while, and had each deposited a twenty-mark note … What was left was two, scrawny little men whose wallets allowed them to buy young healthy, if half-starved boys. Details of the night just past swim into the boys’ consciousness. ‘Yuck!’ says Ludwig. ‘Yes, it makes me feel sick. Never again …’

Not a side of Berlin the Nazis, waiting in the wings when Haffner’s novel was first published by Bruno Cassirer, were sure to like.

January 1933. Along comes Hitler, Himmler and the rest of the crew. A few weeks later Bertolt Brecht leaves the country, not to return for another sixteen years. In May the SA start burning books: a clear night outside the University of Berlin, songs and a torchlight parade, then Joseph Goebbels with a few well-chosen words. ‘These flames not only illuminate the end of an old era, they also light up a new.’ Perhaps Haffner was there watching his soon-to-be-banned book burn, or Willi or Ludwig, looking on curiously as ordinary citizens helped storm troopers throw Thomas and Heinrich Mann, Remarque and even HG Wells onto the fire. Maybe the boys got an idea; maybe they joined up, died in France, or came home to continue their seedy lives. Either way, the last thing we know about Ernst Haffner is that he and Cassirer were summoned sometime in the late thirties to appear before the Reichsschrifttumskammer (RSK, a Nazi writers’ union) to explain themselves. I doubt the meeting went well; and wonder what Haffner might’ve said to excuse his entartete kunst (degenerate art). ‘Well, I just wrote it as I saw it, gentlemen.’ Followed by the usual Nazi lines about vӧlkisch art, self-sacrifice and positive images of the Fatherland. Haffner defending himself in the same way Trumbo, Shostakovich and a hundred others had to – unsuccessfully, it seems, as at this point Haffner disappears from the history of Germany, and literature itself.

Blütsbruder is honest, unaffected, unconcerned about whom it offends or entertains. Like Pasolini’s 1955 novel The Street Kids, it accuses the adult world of neglecting, or abandoning, their kids, leaving them to get by in a world many would rather not read about (not unlike the tens of thousands of ‘wolf children’ left orphans in the rubble of 1945). Blütsbruder is an authentic book; its author more of a mystery than any of its characters, plot, themes. So why have so few people read it?

June 14, 2025

Wise Blood

I’ve got eight hundred words to tell you about Flannery O’Connor. It’d take considerably more, but this is only by way of an introduction. O’Connor was Southern, very Southern (listen to a recording). Born in Savannah, Georgia, she lived a sad (but happy) sort of life, succumbing early (aged 39) to lupus. Sad/happy in the same way her work was strange/beautiful, full of horror, but redemption. Maybe because she was Catholic, very Catholic, and wrestled with religious contradictions her whole life. The standard image is of O’Connor on the porch of her country home at Milledgeville, feeding the lyrebirds, clutching her calipers.

Young O’Connor was precocious, bookish, a loner, never a kid to suffer fools. Apparently, she taught her chicken to walk backwards (see the 1932 footage of her as a child trying to convince the world), but we may never know. The strangeness of a strange chicken lingered, manifesting in potato peelers and dwarfs. But for now, I discovered her through her short stories, nearly all masterpieces. Here’s Joy Hopewell, a leg lost in a childhood shooting accident, going on a picnic with the bible salesman Manley Pointer. Alcohol is involved, condoms and Corinthians, before he asks to look at her prosthetic leg. About now I, you or anyone gets this strange feeling, like, Where the hell is this going? Well, you learn with O’Connor, just hang on for the ride. Or what about her best-known story, A Good Man is Hard to Find, wherein a holidaying family roll their car and end up in a ditch. Three men with guns appear, offering help. Grandmother recognises one outlaw called the Misfit, and this seals the family’s fate. But this isn’t just some true crime gore. God, faith and grace are always lingering, the Misfit explaining

I found out the crime don’t matter. You can do one thing or you can do another, kill a man or take a tire off his car, because sooner or later you’re going to forget what it was you done and just be punished for it.

From the stories to the novels. The two, at least, she wrote, forming a new theology, a Deep South biblical tale-tellin’ that drips with regret, confusion, insanity. Like O’Connor needed to invent a way of combining place and time, people and faith, past and present, the death she was staring down every day, and the hope for some sort of eternal life. In the form of Wise Blood, a 1952 novel that transcends time, and lands up on almost every list of books y’all gotta read. John Huston’s 1979 movie is worth a look, but it’s in O’Connor’s sparse, give-nothing-away prose that the full shocking experience lies.

Firstly, we meet Hazel (Haze) Motes. Newly discharged from World War II, he returns to his Tennessee home to find it deserted. He buys a hat and coat and, looking every bit the preacher, catches a train to Taulkinham, where he finds a phone number on a bathroom wall and calls a prostitute named Leora Watts. But Haze is more interested in telling her about his newly discovered theology, or anti-theology, as it turns out, where ‘the blind can’t see, the lame don’t walk, and the dead stay that way.’ Haze begins his mission to establish the Holy Church of Christ Without Christ. He sets about convincing others, but maybe just himself, that everything he’s been taught about God is a lie.

Your conscience is a trick, it doesn’t exist, and if you think it does, then you best get it out in the open, hunt it down and kill it.

Violence is ever-present in O’Connor’s work. It acts in opposition to whatever she understood to be grace. This random, cruel (but slow) twisting of the knife between the ribs. So, Haze meets an eighteen-year-old zookeeper named Enoch Emery who has just been kicked out of home by his abusive father. He tells Haze about the notion of wise blood. The idea that wisdom, the path forward, the answer to the question that’s never been asked, is in certain people’s blood.

Enoch’s brain was divided into two parts. The part in communication with his blood did the figuring but it never said anything in words.

Then comes the potato peeler demonstration, and as Haze and his new disciple watch, a blind preacher named Asa Hawks and his daughter, Sabbath Lily Hawks, disrupt proceedings. Asa, we later find out, (apparently) blinded himself at a revival meeting when he ‘thrust his hands into [a] bucket or wet lime and streaked them down his face.’ Soon, the Hawks’ ministry of two goes head-to-head with the Motes’ anti-ministry and things get stranger. Emery thinks his Christless church would work better with a saint, and breaks into the local museum to steal a mummified dwarf.

In a way, all of this is secondary to the character of O’Connor herself. A plain, homely, unmarried woman who I, and many others, have spent years trying to understand. There are hints: ‘I don’t deserve any credit for turning the other cheek as my tongue is always in it.’ Maybe it’s me, reading too much into this part-fiction, part-spiritual myth? O’Connor was a writer who died too soon, entering her own mysterious world, leaving a handful of brilliant stories and two great novels. Who believed ‘people without hope not only don’t write novels, but what is more to the point, they don’t read them.’

May 17, 2025

Pedro Páramo

Rulfo was the great Mexican and, later, by extension, Latin American writer. He was born in Apulco in 1917 at a time of radical change and experimentation in literature (Edgar Rice Burroughs was still publishing Tarzan novels, Conrad, The Shadow Line, but meanwhile, Ford Madox Ford had just produced The Good Soldier and Joyce was busy at work on Ulysses). His fame today rests upon two slim volumes: a book of short stories called The Burning Plain (El Llano en llamas) and one novel, Pedro Páramo. Like some of the other great one-novel writers, we’re left wondering why he didn’t continue. Was it, like Harper Lee, that he had gotten it so right? Or did he doubt he could do much else with the form? Or, like Salinger, did the whole thing give him the shits? Either way, Páramo (the narrator’s father’s name) is a book that created a genre. A young Gabriel Garcia Marquez credited it for showing him the way forward (magical realism) with his breakthrough novel, One Hundred Years of Solitude. After reading it, ‘I couldn’t sleep until I had read it twice.’ Eventually: ‘I could recite the entire book from front to back and vice-versa without a single appreciable error.’

Such is the power of the writing, and the ideas, seamlessly welded together, poetic, vague, suggestive, praising and denying god in equal measure, ignoring boundaries between the living and the dead. But not just a ghost story. Yes, there’s a touch of Turn of the Screw, but mostly this is a book about how we, and our ghosts, co-habit the earth. It has something of Joyce’s ‘The Dead’, where Gabriel Conroy attempts to deal with his wife’s lack of interest on their big night alone at the Gresham Hotel. Gretta is caught up in the memory of Michael Furey, an old flame who died at seventeen when coming out (already sick) in the rain to meet her. Gabriel realises Gretta is still in love with Michael, and that memories ‘fade and wither dismally with age.’

Although there’s no fading in Páramo. Beginning with the narrator (until he dies, halfway through), Juan Preciado, crossing Mexico’s burning plains on his way to the town of Comala, in search of his father, the titular Páramo. Preciado has just promised his dying mother to find his father, maybe as some sort of closure on behalf of them both (although, as Joyce shows, this never ends well). Then Rulfo starts to shift the goal posts. Preciado arrives, and makes his way to the Eduviges home, where he’s woken during the night by screaming. Not to worry, Damiana Cisneros offers to take him to her house, but disappears on the way. Somehow, he ends up in an old shack, living with a naked brother/sister-husband/wife combo, before dying and being buried in a coffin beside a woman named Dorotea. From here he just listens to the stories of the dead. Because in Comala there is no distinction between those above and below the ground.

You might be guessing this isn’t Bryce Courtney. The plot is almost non-existent, and you can’t really be sure of anything, or anyone, you’re reading about. It takes a while to get used to, but when you give into it, you come to feel that plotting, predictability, reliance on common tropes like falling in love and robbing banks, is all a bit silly. This is real storytelling; a dark fable, told by a god around a campfire, or more probably, at the gates to Purgatory (several of Rulfo’s characters seem to be trapped here). The story is about how, like Gabriel, we cling to possibility long after it’s gone. Preciado learns: ‘The secret is to die, when you want to, and not when He proposes. Or else to force Him to take you before your time.’

Comala is a real ghost town (‘There was no air, only the dead, still night fired by the dog days of August’), but the dead are no less living than us. So now we return, omnisciently, to the time of Pedro Páramo. Who, at a young age, falls in love with Susana San Juan. It doesn’t end well – she leaves town with her father and the heart-broken Páramo turns his attention to money and power. He gets rich, runs the town, tries to convince Susana to return, comes on to most of the local women and eventually marries a girl called Dolores, who has a baby called Juan. Unable to measure up to Susana, Pedro sends his wife and son away to live with her sister (hence the beginning of the novel). Among Páramo’s collection of illegitimate children, a boy named Miguel becomes a rapist and murderer, eventually killing the local priest’s brother. Susana returns to Comala, but she spends her days (Gretta-like) mourning her dead husband instead of showing interest in Páramo. She dies and Páramo (according to Dorotea) spends ‘the rest of his days slumped in a chair, staring down the road where they’d carried her to holy ground.’ Eventually Páramo lets ‘his lands lay fallow and [gives] orders for the tools that worked [them] to be destroyed.’ The locals leave, and Comala to become a ghost town. Hence the living, hence the dead.

This town is filled with echoes. It’s like they were trapped behind the walls, or beneath the cobblestones. When you walk you feel like someone’s behind you, stepping in your footsteps.

The feeling many of us have, stepping out at night to lock the car, or take out the rubbish. A presence, in front of us, behind us, whispering something we’re unable to hear.

Pedro Páramo is a poem to love, to loss. Rulfo (who lost his own parents at a young age) tries to make sense of the world through a monochromatic poem (Rulfo spent much of his life as a photographer of Comala-like landscapes) describing a world that dies, but doesn’t. That falls victim to one man, his regrets, his rage at losing the one thing we all need most. I’m not saying any of this as a way of explaining the novel; I can’t. Like most novels on my list, it has to be read to be understood, felt, known. This refusal to be categorised defines all of the truly great books: not a word too many, too few. Comala is a region ‘where everything is given to us, thanks to Providence, but where everything is bitter.’ A more reliable glimpse, perhaps, of our own world.

May 12, 2025

Under the Volcano

There seems a niche market for alcoholic, abusive, self-destructive writers with a death-wish. Dylan Thomas, Hemingway – although Malcolm Lowry was, and is, by far the most interesting drunk scribbler. He suckled the teat at 14 because he felt neglected by his mother and, later, guilty (for the rest of his life) about the suicide of his Cambridge roommate, Paul Fitte, whose homosexual advances Lowry had rejected. Under the Volcano is an alcoholic novel. Reviewers and commentators can’t last long without reaching for a glass, or bottle, of the Consul’s mescal. The Consul being Geoffrey Firmin, the protagonist (although that term suggests forward movement, and the Consul really just stumbled) who is in fact an ex-consul, as there are no British interests in the Mexican town of Quauhnahuac, nestled below a pair of volcanoes with names too long and unpronounceable to bother with. This is the booziest of novels. Not bad booze, destroying the Consul, but some sort of magic water, creating him from the ground up.

But now the mescal struck a discord, then a succession of plaintive discords to which the drifting mists all seemed to be dancing … It was a phantom dance of souls, baffled by these deceptive blends, yet still seeking permanence in the midst of what was only perpetually evanescent, or eternally lost.

Lost, like Lowry (1909-1957) himself, born and raised in relative comfort, teenage golf champion, an honours degree in English. But like all great writers, he couldn’t give a shit about that. To his parents’ horror he worked as a deckhand on a steamer for five months in 1927, later incorporating this experience into his first, forgettable, novel, Ultramarine (1933). He then might’ve drifted back to a comfortable teaching job, or bank, but instead, set off on one of the most remarkable writing lives imaginable, his discontent and self-loathing stirring in the bottom of a bottle of tequila’s big brother, mescal. And Lowry was the worm, a lush, soaking it all in until his tragic, mysterious death by grog, or pill, or misadventure (you decide).

Because Under the Volcano is one big misadventure. Eleven of the twelve chapters are set (fittingly) on the Day of the Dead (November 2) in 1938. Firmin is constantly pissed. He is Lowry, and Lowry the Consul, wandering the world in search of … meaning, more booze, or (like Hemingway rising early, going downstairs and fetching his shotgun from the basement) death. The Consul is Faust (reappearing constantly in the text) making a deal with the devil, offering up his soul for alcoholic salvation. This, a book full of symbols, especially horses.

… Ah, to have a horse, and gallop away, singing, to someone you loved perhaps, into the heart of all the simplicity and peace in the world; was that not like the opportunity afforded man by life itself?

Because here’s the thing about Volcano: like the best books (Ulysses, the Bible), it’s far greater than the sum of its parts. In a sense, it just concerns Firmin, his unfaithful wife Yvonne, who returns to him for this single day (the twelve chapters matching the twelve hours he has left), his brother Hugh Firmin, who’s had an affair with Yvonne (there are others). All of these people betraying the central figure of what’s become (after being out-of-print at the time of Lowry’s death) one of the twentieth century’s top ten books. All of the great themes – for example, our failure to meet our potential (the failed consul Geoffrey, the failed actress Yvonne, and Hugh, the musical child-prodigy who never made good). The book rings with poetry (‘I have resisted temptation for two and a half minutes at least’), sings the most lightly-worn philosophy (‘How, unless you drink as I do, could you hope to understand the beauty of an old Indian woman playing dominoes with a chicken?’), drips with a near-proof feeling of presence, place and being that saturates each page with the God of Death (Mexican style), of threat (the ever-patient volcanoes), the cheapness and briefness of life, the futility of trying in a world where everything has been decided, long ago.

Nothing is altered and in spite of God’s mercy I am still alone.

Alone. Lowry’s first wife, Jan, tried to help him, and his second, Margerie, who supported him for years in a dozen different homes, especially their beach shack in

Dollarton, Canada (across the bay from the SHELL refinery, its glowing sign missing its ‘S’), before this burnt down, the Volcano manuscript saved from the flames by Margerie. Neither woman was Yvonne. Perhaps his mother, Fitte, or maybe Lowry was just born wired to be a writer, with its attendant miseries.

Lowry spent his life perfecting one book. He planned to make it the centre of a trilogy, a great myth to be called The Voyage That Never Ends, but spent the rest of his time fiddling with work that never matched the potential of Volcano. This is a book that seems to defy explanation, that can’t be understood until read, until you are tumbling down the ravine, shot by the local police, coming to rest beside a dead dog whose name, reversed, might really mean God.

Thanks for reading Datsunland! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

January 10, 2025

One of Two People

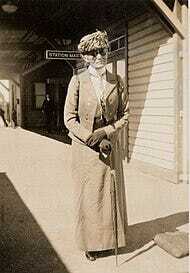

Daisy Bates, or Kabbarli (grandmother) as her ‘natives’ called her, is best remembered as an eccentric Edwardian, done up in a white blouse, stiff collar and ribbon tie; a dark skirt, sailor hat and flyveil. Bates always maintained a ‘fastidious toilet … to the simple but exact dictates of fashion as I left it when Victoria was Queen’. Most people would visualise her waiting for the train at Ooldea Siding, or back at Yooldilya gabbi (Ooldea Soak), bringing her warmth, charity and strong, healing hands to the local Wirangu people. The inimitable Bates lived alone in a tent with her collection of Dickens novels, in this inhospitable chunk of desert, 190 kilometres north of Fowler’s Bay, from 1919 until 1935. Many of us might not realise that Daisy May O’ Dwyer, once-time wife of the almost-as-infamous Harry ‘Breaker’ Morant, was just as comfortable walking the streets of Adelaide as trawling the desert for young Aboriginal girls to mother.

Bates, like many of the grand figures of Australian history (read Percy Grainger), was a mass of contradictions: conservative Edwardian and bigamist; ethnographer and shonky journalist (in 1908 she met a group of Aboriginal women in the Murchison district, every one of which, she claimed ‘… killed and ate her newborn baby, sharing it with every other woman in her group’); inspiring (an outback proto-feminist) but, in the end, sad; loving, but impossible to love.

In her day, Bates was a major national figure. She was almost as well-known as Don Bradman (who also came to live in Adelaide in the mid-thirties) and Phar Lap, Squizzy Taylor and Billy Hughes. Bates was the original Geraldine Cox, running a one-woman mission for a people who were, in her opinion, destined for extinction. Whereas Cox’s Sunrise Children’s Village is all about creating futures, Bates’ work was more about soothing the fatal wound of history.

Bates was brought to Adelaide by the travel writer and novelist Ernestine Hill (best known for her 1941 novel about Matthew Flinders, My Love Must Wait) who had persuaded The Advertiser’s managing editor, Russell Dumas, to offer Bates money to write a series of features about her desert experiences. Hill would be employed to help her. Bates was more than happy to oblige. She had come to believe that she’d gathered as much material about the desert Aborigines as she could. Also, the United Aborigines Mission (UAM) had set up in Ooldea Soak in 1933 and stolen at least some of her thunder. With typical temerity she explained, ‘[The mission’s] coming has brought my work of investigation to a dead end. Of course, I encourage my natives to go to the mission and stay there … one must play the game, you know.’

Bates was soon set up in The Advertiser’s offices in King William Street. A local journalist described the scene: ‘She had a glass-lined cubby about ten by eight … Mrs Hill had the air of a nurse maid, utterly unable to control her charge … she did not seem to have the right feeling for Mrs Bates.’

Hill was being paid to ‘assist’ Bates, but it is now generally accepted that she had much more than a secretarial role in helping prepare the features that were published as ‘My Natives and I’. Bates was 76 years old, with failing eyes, a ‘sallow and thin’ face and hoarse whisper. Still, Hill later claimed, ‘I was careful, and she would have wished it, that all the material … was exclusively hers.’

The grand dame of Adelaide was soon making up for a lifetime in the desert. Of an evening she would walk to her room at the ‘South Australian’ on North Terrace, where she was the in-house celebrity. Hill later wrote of this period: ‘The house phones at the South Australian were carolling all day, flowers, letters, notes to be delivered … she was the friend of the world, inviting it to dinner, luncheon and tea. Greeting a dozen at a time she mustered them all to the dining room at the bang of a gong.’

Bates was invited across the road to Government House (but turned down the invitation) and went on a shopping spree on the proceeds of her writing. After years of tent life, the temptations of the city were too much. Just before Christmas 1935 she worked her way along Rundle Street’s department stores. Her young companion on that day, Josephine Wylde (daughter of an Advertiser editor), said that ‘she flitted from counter to counter … collecting things she though we would like as she went. My mother worried that she may not realise how much she was spending … but she sailed on majestically: “It might be my last Christmas and I am enjoying it with children.”’

It seems she loved children. Her own son, Arnold Bates, was born in 1886. At the time, she was bigamously married to Jack Bates. Arnold fought in World War I and later moved to New Zealand. When Daisy attempted to contact him in 1949, he wanted nothing to do with her. Arnold realised he had always come a distant second to his mother’s ‘natives’.

Such was Daisy’s mindset, and determination. She had been a self-declared ethnographer since 1904, when she began collecting Aboriginal vocabularies for the WA Registrar-General. It’s likely this is where she first learnt of the plight of indigenous Australians: exploited by station owners, living in poor conditions, far from decent health and education services. Perhaps not all that different from today. Bates often expressed her opinion of well-meaning government agencies and missionary societies. ‘The most that can be said of these efforts is that the native exists, or, perhaps the better would be, suffers, a little longer; his ultimate disappearance is only a matter of time.’ This statement must be taken in the context of the time. It’s not that Bates wanted them gone (after all, she devoted her life to their welfare), but she always believed that there was ‘no way of protecting the Stone Age from the twentieth century.’

By January 1937, with her bank account overdrawn, and intending to research a new book, Bates moved to Pyap, near Loxton. She’d recently sent her collected articles to a London publisher, but on the way the plane had crashed into the sea. The bags were salvaged and the articles forwarded to John Murray, who eventually published them as The Passing of the Aborigines. Although out-of-print today (for obvious reasons), after appearing in 1938 this book was read and admired throughout the world, affirming Bates’ reputation as the authority on Australian Aborigines (although many disputed this).

After years in the Riverland, and a mental and physical breakdown, Bates was hospitalised in Trent Hospital, South Terrace (St Andrew’s) in 1945. The old wanderlust soon kicked in and this time she went to live at Streaky Bay, hoping that she might run into some of her old wards.

A friend, Beatrice Raine, invited her back to Adelaide in 1948 to share a house in the Hills. Bates was almost ninety but showed no signs of slowing. Upon her return to the city, she tried to contact her son in New Zealand. She had always carried a picture of him as a seven-year-old. When he refused to talk to her, Bates told a friend that ‘he must have lost his memory’. This, she convinced herself, was the only way to explain his rejection. But, according to a journalist who met Arnold Bates, he had no feeling for her or her ‘legend’ at all.

By 1949 Bates had become the grand old dame of Adelaide again. She still dressed in her Edwardian finest, parading along King William Street. Cars would slow to look, and kids would ask mums, ‘Is that Mrs Bates?’ On a good day, an Adelaidean might see the Don and Daisy in a single afternoon. Bates would often get lost, confused, and ask for directions. She’d wander onto roads and have to be helped, but no man or woman alive was about to tell Daisy she should be home beside the wireless.

One day she stood outside Government House, demanding to see the Governor. To save everyone embarrassment, a local policewoman, Alvis Brooks, convinced her that her car was the Governor’s own limousine, and Bates allowed her to drive her home.

Over the following 18 months, Daisy moved to Torrens Park, and then St Margaret’s Convalescent Home at Semaphore and, finally, to a private hospital at Prospect where, on 19 April 1951, almost blind from sand blight, small, weak, but still proudly defiant and mentally sharp, she died. She was buried at North Road Cemetery with a sprig of desert pea on her coffin.

It’s worth a visit: row 15S, plot 255B. Ironically, Daisy is hemmed in by the suburbs, nearby car yards and back yards full of washing flapping in the breeze. But, of course, she’s not. She’s still in her tent, reading David Copperfield, fixing cuts and grazes, helping her Aborigines. And for what other reason than a deep well of compassion and love? Sometimes, in our struggle to understand this complex woman, we lose track of this one simple truth.

Tom Playford paid tribute to her, but didn’t think her worth a state funeral. Although born in County Tipperary, Ireland, Kabbarli made the desert, and the streets Adelaide, her home. For this, we should all be grateful.

December 7, 2024

The Elephant Didn't Ask to be Washed

Franz Reichelt

While casting around for a suitable metaphor with which to represent the business of Australian letters, I stumbled upon the rise and (very sudden) fall of Franz Reichelt. Reichelt was a 33 year old Parisian tailor with a very big moustache who dabbled in parachute making. One day in 1922, he arrived at the Eiffel Tower to test his new all-in-one wearable parachute. Grainy newsreel shows him proudly modelling his handsomely-tailored suit before ascending the tower, climbing onto a handrail, looking over with a seemed-like-a-good-idea-at-the-time expression, spending forty seconds trying to convince himself to jump, moving hesitantly forward, moving back, forward, back, before leaping. And that’s what I’m interested in. That fraction of a second before he finally jumped. Only humans (especially writers, but I’m getting to that) have the capacity for that sort of self-delusion. After the failed test, industrious Parisians are seen measuring the depth of Reichelt’s impact crater, then removing his corpse.

9.8m/s/s

I’d like to understand what motivates a person to write. To give up thousands of hours of valuable time to scribble a story about a man who leaves his wife; life in a small town after the discovery of a body of a person related to an alcoholic detective caring for his cantankerous father; the fun-times had by a pair of school friends on an adventure (&c.). The reality is

a) one in many hundreds of novels might get published, and one in a hundreds, thousands of these might find an audience;

b) very little to no money will be made from the venture;

c) the writer won’t end up joining the pantheon of authors they’ve admired since childhood;

d) the process will take time away from partners, children, friends, as well as the carrying out of otherwise sensible (paid) work;

e) the process of writing will keep raising a bar which, by attempting to reach it, will only cause it to rise even further;

f) (&c.)

And yet, every day, hundreds of new plays, novels and stories are begun, each author believing something new, untried, groundbreaking will make it onto the page and change lives. According to Steven Piersanti (Berrett-Koehler Publishers 2021), too many books are now being published (3 million+ per annum in the US alone), the book marketplace is oversaturated (meanwhile, people get most of their information from social media), sales are low (on average, a few hundred copies, and declining), books by non-A-listers won’t get shelf space in the few remaining bookshops, and most books now only sell to authors’ and publishers’ communities. The days when a Lucky Country could be found on most Aussies’ bookshelves are over (perhaps because the consensus found in such books is now missing). Recently, I was asked by a state writers’ centre to give a talk about writing, books, the ‘journey’ (@9.8 m/s/s), but declined, saying the only thing I could honestly tell prospective writers is don’t bother (which probably isn’t the message they want their paying members to hear). But after nearly thirty years of scribbling, a dozen published novels, half a dozen unpublished novels, short stories (&c.), it seems what started off as good, noble and necessary ends with a Lasseter’s Reef-sized feeling of dread. More, the suspicion that writing is a form of addiction as bad as alcohol, smoking and gambling and, like these, grows from a writer’s

a) lack of self-esteem;

b) reluctance to accept the world as it is;

c) dislike of other people;

d) inherited and/or acquired depression.

Point d) comes with a range of types and outcomes such as

a) boozy, self-destructive writers (Malcolm Lowry, John Berryman, Dylan Thomas);

b) the ‘haunted’ (Virgina Woolf, Ernest Hemingway, Sylvia Plath);

c) those who can’t see any way out (Stefan Zweig, Walter Benjamin); and

d) the overthinkers (Mark Fisher, David Foster Wallace)

And what’s worse, for every well-known suicide there’s probably another hundred lesser or unknown (especially writers who, like Reichelt, bet on success, and lost). Jonathan Franzen wrote in his famous ‘Harper’s essay’ (Why Bother?) that

the available evidence suggests that you have become a person who’s impossible to live with and no fun to talk to. And as you increasingly feel, as a novelist, that you are one of the last remaining repositories of depressive realism …you ask yourself, why am I bothering to write these books?

Moreover, the nagging question: did I start writing because I was depressed, or did I become depressed because I kept writing? In a way, a pointless question. The effect’s the same.

Hillcrest

I suspect writers are born, not made. This is my problem with writing courses, degrees, workshops (&c.). The equivalent of giving a classroom full of Year 9s their first vodka (or line). If a writer really wants to write, they will. I started off reading Asterix, Hardy Boys, sitting on my Hillcrest back lawn on long, summer nights tackling my first Agatha Christie. It always seemed important to find out who’d killed the maid. I was always around books. Over time they became a manual on how to survive an otherwise dull, suburban life. This led to Crime and Punishment, The Vivisector, the feeling the ever-present shitiness of the world could be explained (and maybe ameliorated) through stories. I was, writers are, hard-wired to see the world this way. So it makes sense that at some point they think, I could do that.

Because they can – anyone can. Having started on this path, having written novel #1 (and having it rejected), a new level of delusion sets in when we say, Of course, that’s what I did wrong: a lack of focus, wavering POV, predictable plot (&c.). We try again, but novel #2 has a different set of issues. Somewhere around novel #4 we produce something publishable, and it gets read by family, friends, a few kind strangers, and this gives us enough encouragement to keep going. At some point (with literary greatness still eluding us) we decide we’ve invested too much time and effort in this gig to give up. You can’t, after all, return a half-eaten Big Mac and say you never really wanted it. Better to keep eating. Maybe that’s what Reichelt thought, standing on the handrail, looking down at his supporters, all of them pretending to believe in him as much as he believed in himself.

God bless Peter Ross

You thought that was grim? In the past few decades, the Australian publishing industry has become a washed-out junkie searching for a cheap literary hit, publishing derivative books about happy dragons, alcoholic detectives, Thelma and Louise-style girlfriends moving to Provence to start a cake shop. The big, ambitious stories have gone, replaced with trembling yarns about our endless insecurities, managing, at the same time, to alienate any reader over thirty. More books by fewer authors with (ironically) less diverse stories; less (or no) risk-taking in content and form; a drift towards biographies of croquembouche-making or ball-kicking Aussie icons. Meanwhile, publishers costs go up, cover prices, bricks-and-mortar struggles, we have a less literate (and educated or critical thinking) nation of blokes and chicks who’d prefer to hit the local Westfield, the still ever-present diet of everything American (propped up by a lazy mainstream media), fewer university courses in the fine arts, art, anything involving text, fewer universities who give a rat’s about the things that made them great in the first place. Peter Ross used to have a crack at the Yarts on the ABC every Sunday afternoon. There was a feeling that watching Mother Courage or listening to the Rach 3 was somehow improving. But that seems to have gone, too. Ironic, as we need improving more than ever.

As a teacher, I’ve witnessed thirty years of dropping standards in our classrooms as underfunded and -supported teachers recycle 28 torn, coverless copies of Holes for yet another wrist-slashingly grim term. The feeling that Holes is necessary; that reading and writing, like long division, have to be endured. That nothing good can come from this literary car-crash. That whatever’s in that book (especially if you’re a boy, especially if you never see a male teacher) has anything to do with the issues you deal with on a daily basis. As the YouTube gen (not surprisingly) stare blankly out of the window (or peer at the ever-glowing and growing marvel in their crotch). As Walliams et al. pass off fart jokes as the solution. Meanwhile, the PE department gets a new hall, a bus to take the kids to yet another Intercol. But what’s so different, I guess, than the pots of money thrown at sporting clubs to allow us to become the World’s-Best-Perspirers (not that we come anywhere close). Funding might help creative types, too, but our arts departments have an East German-style habit of disappearing into the night. Even then, most writers give up on state support after a healthy batch of rejected funding applications (despite the promises of endless cultural policies).

A Unshakeable Nostalgia for Strawberry Pops

So a writer has a few books published, makes a slight reputation, attends a few book festivals, and what happens next? There’s no career progression. No progression. No career. The only thing Australians like better than ignoring culture is forgetting it. The neo-Oprahists remind us to ‘Never give up!’ But that was a sentiment borne of hard work and reward. No more. Now, even if you are the next-big-thing, you’ll still have a use-by date (Eighties’ bands playing the Victor Harbor RSL). Books are products, and you can’t keep selling Strawberry Pops when people want Tasty Bites. So you hit the mid-list. Here you have time to reflect on where it all went wrong. How people said such nice things at the beginning but now, don’t say much at all. In fact, can’t. For one, the Australian media has lost interest in books (reviews, book clubs, giveaways, summer reading promotions &c.). Our political class, too. I can’t remember the last time I heard an Australian politician extolling the virtue of an Australian novel.

Franz (again)

People always have told and will tell stories. Perhaps the issue’s more about the forms we choose, but the 100K+ word novel seems to have gone the way of the Mitsubishi A380. Then the 90K, 80K (&c.). In the end, all we’re left with is the fag ends of a cultural phenomenon that peaked in the nineteenth century, prospered in the twentieth, and now lingers in the S-bend of our national consciousness, and memory.

Writing’s like the guy who washes elephants. We only need one guy, but there’s a line of thousands wanting a go and when they do they decide they really like washing elephants and that’s all they want to do. So they tell their friends, then their friends want to wash elephants, too. And then the guy who runs the circus says, Please, stop wanting to wash elephants – I can’t even afford to feed this one. So now all of these people have set their sights on washing elephants, but instead of saying forget the elephants, we say, Here, come and study elephant washing in more detail and you’ll have a better chance of getting a (the) job. We put an enormous amount of effort into learning the art of elephant washing (study tours, residencies &c.) but the job never comes up because the elephant dies and we’re all sad and some wannabe elephant washers even kill themselves. Why? Because humans are sick, self-deluded puppies. Even after the elephant’s corpse sits rotting in the sun for a few years, we keep washing it. And then, the failed washers sit around looking at beautifully illustrated books of elephants and tweeting wistful elephant quotes and saying, What if? But really, if you act like a grown up and decide to do something apart from washing elephants, your life will probably be okay.

But even stranger than all this is the fact that even the people who did get a job washing elephants end up depressed. Maybe it’s because all writers are like this. Maybe we think that washing elephants will save us from ourselves? Take for instance the American poet John Berryman (of The Dream Songs), climbing onto Minneapolis’s Washington Avenue Bridge in 1972, looking back, thinking (possibly), What was that all about, and jumping (@9.8m/s/s). Early in his career (as a passionate poet and teacher) he’d explained the nature of the elephantine beast: ‘To write is hard and takes the whole mind and wants one’s whole time …’ But just before his suicide he’d decided: ‘Hosts of regrets come and find me empty. I don’t feel this will change, I don’t want anything or person, familiar or strange. I don’t think I will sing anymore just now; or ever. I must start to sit with a blind brow above an empty heart.’

All of which is why I come here today to tell you to forget the writing game. Anyway, it’s not like there aren’t enough books already. I mean, you might write something better than Anna Karenina, and I’m sure you’ll eventually write something beautiful, I’m sure the world will be a better place for what you’ve written, but will all of this make up for the time you’ve lost? Writers are optimists, trying to fill the void with meaning (or at least asking how this might be done). Hope being the last thing to die, all of that stuff about short rations, and we decide we can’t go on, but we go on because what’s the alternative if you’ve got a big brain? Or, as Flannery O’Connor explained:

People without hope not only don’t write novels, but what is more to the point, they don’t read them. They don’t take long looks at anything …

Either way, if we want to be optimistic, we should remember the world’s going to blow up in 4.7 billion years, and everything will be wasted. Also, 99.9% of all species that have ever lived are now extinct. How are we to know what any of those billions of organisms thought about the weather, sibling rivalry, why the sun kept burning, the price of bread, or even the eternity they now, exclusively, inhabit? Imagine if they’d written it all down! What’s it matter now anyway? The elephant didn’t ask to be washed. He, she or they liked being dirty. As it turns out, we were (and are) the bigger idiots. Despite their peanut brains, and our IBM computer-brains, true happiness can only be found rolling in sand. All of which is a long way of saying, if Reichelt had’ve been honest with himself, he would’ve admitted there was a good chance the parachute wouldn’t open.

September 22, 2024

Patrick White's 'A Cheery Soul'

In a Canberra Times review of Jim Sharman’s 1979 revival of Patrick White’s A Cheery Soul, critic Ken Healey wrote: ‘A Cheery Soul is one of the most profoundly satisfying experiences I have had of Australian theatre. It compares with seeing the whole of Lawler’s ‘Doll’ trilogy in a single day, and exceeds the delight of attending Williamson’s greatest successes.’ The production, a career-defining tour-de-force for Robyn Nevin as the titular Miss Docker, came as more Australians were becoming aware of the 1973 Nobel laureate’s body of work (what Barbara Blackman called the ‘Patrick White Australia policy’). From White’s earlier ‘European’ novels (The Living and the Dead, The Aunt’s Story), through to his fifties masterpieces (The Tree of Man, Voss, Riders in the Chariot), to his ‘meaty’ novels of the sixties and early seventies (The Vivisector, Eye of the Storm).

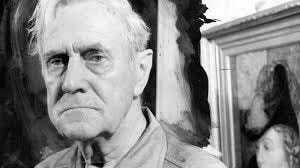

Patrick White

Patrick WhiteBut there was more to White than novels. Born in England in 1912, he returned to Australia six months later, but was back in England at thirteen to attend boarding school in Cheltenham. From there to Cambridge, then London, where he (unsuccessfully) started writing plays (including The Ham Funeral, which was eventually produced by the University of Adelaide Theatre Guild in 1961). Travels, love affairs, a period in World War II as an RAF intelligence officer in the North African Desert. And through all of this, a love of art, music and theatre that accompanied his early struggles as a writer.

A Cheery Soul started as a short story, a part-portrait of Alex Scott, a gardener who worked one day a week at Dogwoods, White’s and his partner Manoly Lascaris’ Castle Hill property. According to David Marr: ‘She was fifteen stone of tough old lady with a crew cut, an army hat and a pair of flapping shorts worn in all weathers.’ As with Miss Docker, she was a good talker; a good soul with a good heart, a no-nonsense woman from a now-lost Australia where everyone had a stray aunt or uncle living in their sleep-out. She loved a beer and, according to Marr: ‘Out of her mouth poured handy hints, maxims, stray facts, anecdotes, recipes, new theories and frank observations.’ In short, perfect Patrick White material. One day, when she was pulling weeds with White, she told him, ‘I am praying that someday you will write something good.’

‘Scottie’ had suffered a mental breakdown working at David Jones, and had become (ironically) an expert on mental illness (once she told White: ‘You’re borderline’). She was a Christian, loved reading the Bible, taught Sunday school, sang in the church choir. White called Miss Docker/Scottie ‘a wrecker, who first of all almost destroys two private lives, then a home for old people and finally the Church, by her obsession that what she is doing for other people is for their own good.’ White realised this limitless obsession dragged down (as much as raised) Miss Docker, and the tragedy was she couldn’t see this herself. That none of us, perhaps, can see our own reflected (as White called them) ‘flaws in the glass’. White saying of his own biography: ‘I think this book should be called the Monster of All Time. But I am a monster …’ This short story and play, then, are catalogues of Miss Docker’s good deeds. As White provides a chorus of opinions to frame the story.

MRS CUSTANCE: She [Miss Docker] would be free to come and go. And she’s in such demand – babysitting – mending – we’ll hardly notice she’s here. Poor soul! Nobody in Sarsaparilla ever did so much good … You’ve got to justify yourself in some way. You can’t just take, take, without you show a little gratitude.