A Modest Proposal

Six weeks walking, studying maps, hobbling on my dodgy foot, all to make one discovery. But that can wait.

It starts in Dublin. The James Joyce walking tour. Along North George’s Street, framed by Belvedere College S.J., where Joyce first learned there is ‘no philosophy so abhorrent to the church as a human being.’ Yes, the Jesuits were fearful, but tempered. As I imagine the young man walking to school, settling in his room, waiting for a dose of Homer, already turning Dedalus in the cold morning air. Cold. Dublin is Liffey-chilled, eye-watering and seagull-squawking. The post office, with its bullet holes, ready to celebrate a century of defiance, although the greatest travesty now is the row of tourist buses parked across the street.

More Joyce! Come on, ladies and gentlemen, keep up, please! As we brave few (including the inevitable Americans, telling us how important Joyce was to their Idaho-childhoods) lean into the wind, imagine the great boy, teenager, young man, trawling these streets for material. We avoid Parnell Square (the old Rotunda Hospital where JJ was born) and head down Frederick Street North (with its peeling apartments, cheap hotels and off licence) to Hardwicke Street. The guide points to what was once the Joyce family home at number 29 (now a block of council flats), and we all try to imagine (but for my part can’t) John, Mary, Stanislaus and little Jimmy heading out for the day, perhaps to the nearby St Mary’s Pro-Cathedral (unlikely). And across there, our guide says, indicating a sagging little Victorian walk-up, you can see the building that inspired ‘The Boarding House’ (written in Trieste in 1905). In Joyce’s day, number 4 was a brothel, (as an Indian man and his wife come out with their several children). Joyce probably spent hours watching the goings and comings. Imagining the lodger, Bob Doran, forced into marrying Polly Mooney, the madam’s daughter (as it still goes on to this day).

Then a couple of teenagers on a loud, penny-sized motor bike start riding up and down Hardwicke Street, past us, closer and closer, grinning, as I recognise this Irish streak. We few foreigners (clutching our annotated editions) seem strangely out of place with the grog shops and Pakistani delis, flats, everywhere, and a few teenage mums with almost teenage kids. And I think, At last, Joyce’s Dublin!

Which brings me to the discovery. Although this early in the trip, I had no idea what I was seeking. Some Adelaidian Leopold celebrating his Orrday (after so many years of dreaming about it). As the stinking dung heap of a feeling began (destined to pursue me throughout my European odyssey): Am I disappointed? Is this what I expected (what was I expecting?)? I thought Dublin would be so…literary, but there are actual people, in trackies, bum cracks, a Subway, Starbucks. And the feeling: Joyce is long gone. He wasn’t even here when he wrote about the place; he hated it. Said, ‘When I die, Dublin will be written in my heart.’ But this Dublin?

No time for thinking. This way please. As the motorcyclists give up, head towards St George’s Church, and the next group of suckers. We continue, heads down, towards the Liffey. Stop outside the Gresham Hotel. By now, my dodgy foot is failing, and I wonder if I should slip away from the group, find a café, and seek Dublin through my own copy of Dubliners. Is that done? Can you just go? Roy and Shirley (Idaho) are monopolising the guide, so… But I stay, and hear about Gabriel and Gretta Conroy (upstairs, staring down across O’Connell Street Upper), Gretta ignoring Gabriel’s lusty hints, telling him about a long-dead lover who’d gone out in the rain to meet her (‘I think he died for me, she answered’). Gabriel’s interest flags, depressed that his wife (on their big night at the Gresham) still longs for Michael Furey. Then, he senses, we are all still living with the dead, and past. Maybe that’s my problem, attempting to animate a dead writer, falling asleep as cold Dublin loses its eternal friskiness.

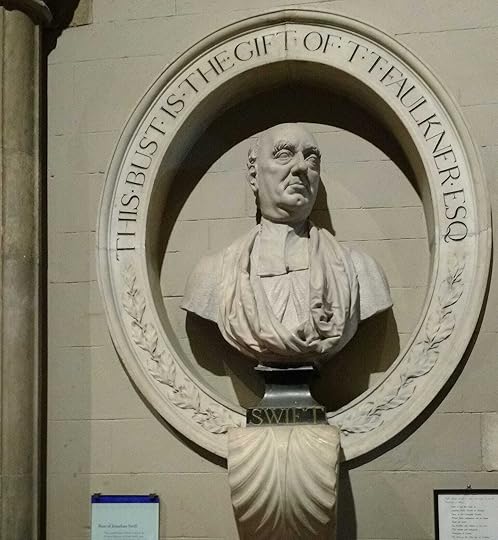

The next day I try again. Jonathon Swift. Dean of St Patrick’s Cathedral, a few minutes’ walk from Temple Bar. I’d re-read Gulliver’s Travels. Studied his biography. Got to know him through his pamphlets (‘A Modest Proposal’, in which he explains how ‘a young, healthy child, well nursed, is, at a year old, a most delicious, nourishing and wholesome food; whether stewed, roasted, baked or boiled, and I make no doubt, that it will equally serve in a fricassee…’). Swift is still giving his sermons. Sarcasm, satire. But a love of humanity, and desire to see people at their best. Even now he can still piss people off (especially those who take him literally).

I spend an hour searching for Swift. In the park beside the cathedral where St Patrick used to covert heathens. In the gift shop, the post-Norman toilet (one of the few in Europe where you don’t have to pay-to-piddle), the North aisle and transept, the graves of Swift and his muse, Esther Johnson (Stella), Swift’s death mask, a selection of his writings (liturgical, and funnier) and his pulpit. As I sit and try to hear him. What sort of voice? Was he funny? Was anyone even listening (refer to his sermon, ‘On Sleeping in Church’)? My little voice is still asking, Where is he? Where are the Lilliputians? The flying island and smart horses?

Enough of this nonsense. London will cure it. A brisk walk through Bloomsbury. Like a dinosaur down Holborn Road, Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Chancery Lane, Fleet Street, Gray’s Inn Road, Doughty Street. 48. Enter and leave through the gift shop (as usual). Into Dickens’ hallway, narrow neat, his front room, and he’s sitting there, planning the next instalment of Oliver Twist. Consulting ‘Phiz’ about the illustrations. John Forster’s just arrived, chatting with Kate Dickens, sewing, reading, taking tea, perhaps, in the small room at the back. Up the stairs to the great man’s study. The walls lined with bookcases, the desk, the writing table where Mr Bumble, Bill Sikes, Nicholas Nickleby and a dozen other characters daily came to life. This is more like it. The small of old paper, leather. The ghosts. Although, if you stop and listen, you can hear delivery vans outside, a helicopter, voices from the gift shop. So, where is Dickens? In his bedroom? I check, but there are just more fans, like me, searching for the keys to creativity, although they can’t be found.

And so it continues. Edinburgh. Conan Doyle at medical school (although his birthplace was torn down to make way for a roundabout and public toilet), Robert Louise Stevenson, learning the art of ‘illustrating death’ as he walks from Claxton Hill to Parliament Square, where you ‘strike upon a room…crowded with productions from bygone criminal classes…poisoned organs in a jar, a door with a shot hole through the panel, behind which a man fell dead…’ In Edinburgh, a thousand fireplaces have turned the sandstone black; the closes still musty, Black Death between the stones, in the foundations and daubed walls. Here, it isn’t the writers as much as the place itself. A city of stories. Rowling scribbling in her café, Robbie Burns drinking a kindness cup from the high ground as the pipers pipe and Dr Jekyll prows the streets, still.

On and on. The voice persists, the feeling. That we populate stories with our own meaning, and those who love storytelling the most, surrender to the illusion most completely. I continue to Berlin, but don’t find Brecht at home (or in the small, monastic bedroom where he died). There are clues: the rooms he didn’t share (due to his adulteries) with his wife, Helene Weigel. She was much more comfortable downstairs in her moo-cow kitchen, her glassed-in garden room, although they’re together again, in the Dorotheenstadt cemetery, a few metres walk form their old digs. Similarly, TS Eliot isn’t waiting out front of Faber and Faber, or smoking in Russell Square, contemplating the Heaviside layer. That’s still there, keeping radio waves in the atmosphere, stories in the streets where they were set, bouncing Sam Weller beyond distant horizons. Hooking people like me, who come looking, full of hopes.

As, eventually, the voice fades. You give up. You no longer care about Wilde’s house, or where he might’ve walked in Merrion Square. The stories are in the mind, the words, the pages, the books that remain. You can go all the way to Hamnavoe to find George Brown, but you might as well visit the local library, let the poetry propagate in your own ether. Joyce left Dublin in 1904. He once said, ‘One of the things I could never get accustomed to in my youth was the difference I found between life and literature.’ Perhaps that’s the key. Between the living and dead, real and imagined, the writer and reader.

Stephen Orr's Blog

- Stephen Orr's profile

- 31 followers