Tudor Alexander's Blog

March 3, 2025

On Writing

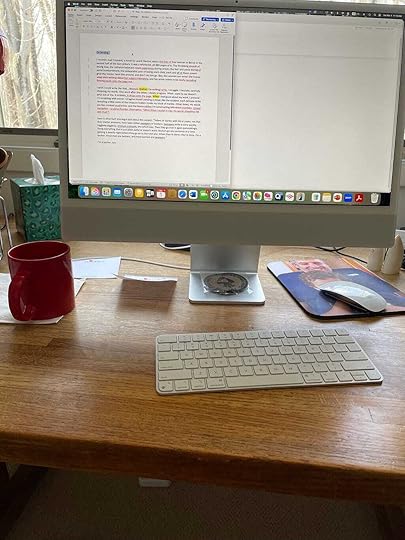

Editing on my desktop

Editing on my desktopI recently read Crescent, a novel by Laurie Devine, about the lives of four women in Beirut in the second half of the last century. It was a whirlwind, all 880 pages of it. The throbbing assault of young love, the catharsis believers experience during prayer, the fear and panic of aerial bombardment, the unbearable pain of losing one’s child, each and all of these scenes grab the reader, twist him around, and don’t let him go. Boy, this woman can write! She knows her subject intimately, and her prose seems to be cascading easily onto the page.

I wish I could write like that. When I write, I struggle. I hesitate, carefully choosing my words. One word after the other, I slowly progress. What I want to say doesn’t pour out of me. It dribbles, it drops onto the page. If I feel good about my work, I pretend I’m sculpting with words. I imagine myself yielding a chisel, like the sculptor, each delicate strike revealing a little more of the treasure hidden inside my block of marble. Other times, my words are mud bricks, and the edifice I’m constructing crumbles.

Here is what Kurt Vonnegut said about this subject: “Tellers of stories with ink or paper, not that they matter anymore, have been either swoopers or bashers. Swoopers write a story quickly, higgledy-piggledy, crinkum-crancum, any which way. Then they go over it again painstakingly, fixing everything that is just plain awful or doesn’t work. Bashers go one sentence at a time, getting it exactly right before they go on to the next one. When they’re done, they’re done. I’m a basher. Most men are bashers, and most women are swoopers.”

I’m a basher, too.

[image error]February 24, 2025

The Good and the Bad

We are conditioned to love happy endings. As a child I learned about the prince who overcomes all obstacles to win the heart of the beautiful (and innocent) princess and holds her happily ever after in his muscular arms. Later I read Romeo and Juliet, aware by then that tragedies happen.

When writing fiction, one must decide between realism and a world where reality is ignored. No hero is only good, nor is the villain only bad. Complex fictional characters are a mosaic of light and darkness, (red and black or straight up and upside down) their negative and positive traits creating a portrait readers will contemplate.

The plot is an extension of that same dilemma. A character’s actions can engage or distance the readers. Cultural differences matter. Societal norms, too. What was taboo yesterday might be acceptable or even admirable today.

Since I grew up in another country and write in two languages, I noticed a difference in how some of my stories are perceived in Romania versus the US. In my novella SMOKE, the main character, Doru, is a Romanian immigrant in Denmark, who gets arrested for manslaughter. In his diary, Doru confesses to being a wife abuser and to having beaten his own father, when, years earlier, the father returned home from a communist prison. Still, he sees himself as the victim of a sad childhood and a rough youth. It turns out that Doru is a bad guy, a member of the Romanian Secret Police.

The novella was very successful in Romania, and a well-known Romanian movie director asked me to turn it into a screen play. (The project foundered for lack of financing.) To this day, Romanian films made by famous directors such as Radu Jude (“Aferim”) and Cristian Mungiu (“RMN”) are dark and depict a gloomy Romanian society troubled by the skeletons in its closet.

Yet, my American readers disliked the novella, complaining about the dark realism with which I had depicted the main character and the authoritarian society which influenced him.

I guess Romanians remember what it means to be forced into political compromise, to survive in a world where most are victims and the law doesn’t apply equally to everyone. Americans like heroes. Happy endings. Sunshine and blue skies. So far, most have been spared having to compromise.

But how do I, as an author, reconcile my two worlds? What do you, my readers, think?

[image error]February 17, 2025

Writing in Two Languages

New York (left) and Bucharest (right)

New York (left) and Bucharest (right)“To translate is to look into a mirror and see someone other than oneself.” Jhumpa Lahiri, Translating Myself and Others

Born in Romania, I grew up bilingual with Romanian and Russian spoken in our home. School was in Romanian, so Romanian became my dominant language. When I was thirteen, I started learning English and by the time I graduated high school, I spoke English at a rudimentary level. Before immigrating to the US, I lived a year in Israel where I spoke English at work. My English improved and when I came to the US, I was rather proficient.

It took me twenty more years to start writing creatively in English. Simply put, I didn’t dare. I wrote novels and short stories in Romanian, and then I asked other people to translate them into English — paid translators and my wife, who, like me, is from Romania, but has an advanced degree in French and English Literature.

And then it happened. I started writing fiction in English, first haltingly, checking my every word, my grammar, obsessed that I was translating from Romanian and employing the wrong syntax. I read aloud to myself. I asked my wife to be my editor. I pestered friends, especially those born and educated here. My heroes were Joseph Conrad and Vladimir Nabokov. I admired and envied Romanian writers, contemporaries of mine, who wrote in English: Andrei Codrescu, Petru Popescu, Norman Manea. They gave me hope. I admired Jhumpa Lahiri who learned to write in Italian.

Writing in two languages is both rewarding and tricky. They say that an immigrant doesn’t know any language perfectly. Nowadays I am more proficient in English, but I “feel” the Romanian language on a more visceral level. I understand the slang. Vulgarities hurt me deeper. Poetry and humor reach me faster.

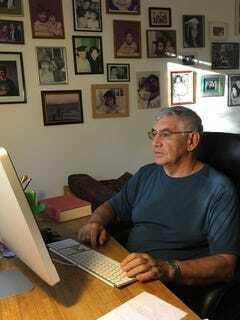

Now that I write mostly in English, I can see an advantage to having two languages at my disposal. When I write, I struggle. I scrutinize every word, rereading until it becomes too familiar to improve. By translating it, I can see my mistakes clearly in a fresh context.

[image error]February 10, 2025

Point of View

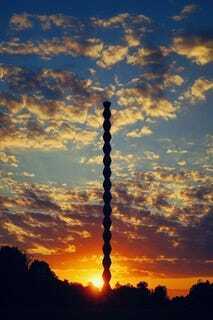

Photography: Vlad Eftenie

Photography: Vlad EftenieWhen I write, I describe the world through the eyes of my characters looking out or my eyes looking in. I get to know my characters well. I understand their quirks, and the tricks their lives played on them. I am omniscient. God.

The omniscient approach distances the writer from his character and allows him to observe the space the character lives in from a broad perspective. It gives him flexibility. The reader, on the other hand, wants to be invested in the character. Stay close to the character’s soul and observe the progression and the change in an intimate way. Not just the facts, the action, but the innermost feelings. As the character’s emotions are on vivid display, it is less work for the reader, more work for the narrator.

I like to do it both ways. Be both. In and out. Omniscient when I feel that I need the wider perspective, otherwise stay within the character. Create drama and tension, until I let go. There is a Romanian sculptor known all over the world: Brancusi. His Infinite Column comprises identical pieces carefully carved, bubbles of stone one on top of the other emulating the mathematical symbol for infinity turned on is head, vertical, going up and up. The column narrows and widens again and again. In and out.

That is how I write. Get close to my character, create drama, and step away again. I know this approach worked for many major writers (Tolstoy, Eliot, Rowling, Atwood, to name a few). AI says this blending of omniscient author and character’s point of view creates a dynamic, rich, layered story I hope my readers will enjoy.

[image error]February 3, 2025

Who’s Behind the Mask?

Who are the real people behind the characters in my stories? Names are changed, physical attributes are altered and often, for the sake of expediency and the strength of the story arc, several people come together to form a single character. Still, when I write about those who are close to me — parents, grandparents, dear friends — I am torn. These are beautiful human beings, thoughtful, passionate, resourceful, and their lives inspire my stories. But they are not perfect. How much should I reveal?

Anne Bernays, a well-known novelist, editor, and teacher writes: “If you’re going to write fiction that’s even vaguely autobiographical — and which of us hasn’t? — in trying to decide what to put in and what to leave out, don’t consider what your friends, neighbors and especially your immediate family are going to think and/or say, assuming, that is, that they ever read what you write.” In other words, throw them onto the pyre of your work. For you to be successful, for your novel to be successful, don’t worry about them. This is easier said than done. Anne Bernays adds: “You don’t want to hurt people deliberately; if you’ve got the proper skills, you can disguise most people, so they won’t recognize themselves.”

Do I have the proper skills? Will I feel a sense of guilt?

My parents are no longer alive, so I cannot hurt them. But by harming their memory, I harm myself. They made me who I am.

When my characters reflect my parents’ or my friends’ very familiar shortcomings, I employ a trick. I invent conflicts and relationships that I cannot know from direct experience, episodes from a war that took place before I was born, arguments I never witnessed, or love scenes I can only imagine. This way, if I ever feel guilty about using them as my source of inspiration, I remind myself that turning truth to fiction is my craft.

My wife, who reads everything I write, says my characters come alive when I care about the people who inspired them. I struggle when it gets deeply personal, I tell her, and she says, just let it flow from the heart.

[image error]January 27, 2025

On Literature and Immigration

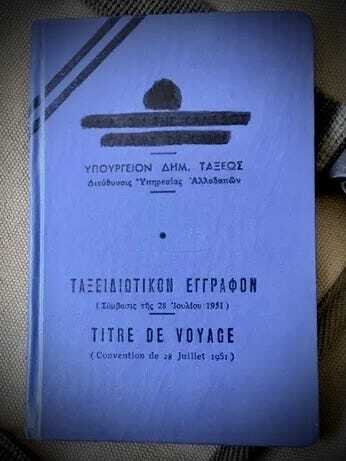

My refugee travel document 1977

My refugee travel document 1977Immigration is a hot and highly controversial topic these days. It affects me deeply and directly, as I am an immigrant. I came to the US in 1977, lawfully, from communist Romania. Very young at the time, I followed the clearly defined steps of the “third country program.” I asked for political asylum in Greece, and, guided by a very nice and kind lady, a representative of the United States Catholic Commission, I applied to be admitted to the US at the American Embassy in Athens. After a successful background check, a medical checkup — no syphilis or TB — and with a letter from my US sponsor, four months later I was granted refugee status, along with a conditional green card which gave me the right to work. Many people from communist countries who wanted to come to America benefitted from this program. There was no drama and no invasion, just a reasonable, well-organized approach which benefitted both the immigrants and the United States. Five years later I became a US citizen.

The immigration experience is often at the center of my writings. My heroes are people who have the courage to overcome the fear of the unknown and who struggle to adapt to their new country and culture. They take a leap of faith in search of political and intellectual freedom, and material wellbeing, despite the heartbreak of leaving beloved family and friends behind.

My new novel, “The Last Patient,” reflects this struggle between a cherished past and an uncertain future. The desire to escape communism for the sake of personal freedom and abundance of opportunity permeates the pages. Toward the end of the novel, my characters, by now safely settled on this side of the Atlantic, still look for comfort in the mantle of memories of the old country and of the loved ones left behind.

The prize of America is not without sacrifice.

[image error]January 20, 2025

Biography and Fiction

John Cheever said that any confusion between autobiography and fiction debases fiction. I like Cheever. I respect him as an author, and I love reading his short stories. Still, everything a writer writes is anchored in his own reality. In other words, it is based on his biography. Whether one writes about Spartacus, about the life of dogs, or an odyssey in the distant future, when one gets to the human element, to feelings and emotions, the author draws from his own experience. How else? Two thousand years ago or two thousand years into the future, and a story has meaning only within the framework of people.

My recent novel “The Last Patient,” (to be published 2/2025) emerged from my life and from what I was conditioned by it to imagine. The novel depicts a world, exotic to some, revelatory and captivating to others: Romania under communist rule, the middle of the 20th century. My characters fall in love, survive the war, bow to power, cheat, resist, dream about defecting, and — well, I don’t want to give it all away yet. I hope I have woven reality and fiction into a strong narrative and an emotional read.

[image error]December 25, 2021

The World Around Her

Bucharest, 1967–1969

From A Family Album: https://alexduvan.medium.com/a-family-album-40829e212764

Schoolyard antics

Schoolyard anticsAmong Lydia’s high school classmates was a young man by the name of Marcus Diaconu. He was tall and broad shouldered and spoke with authority and a disarming sense of superiority, whether to a teacher in class or to his friends in the hallways or in the street. He exuded invincibility. At sixteen he looked like a twenty-year-old and behaved accordingly. His facial features matched his appearance: a straight nose like the ones on old Roman coins, voluptuous lips, brown eyes, and a tall forehead under a mane of brown hair combed backwards. He held his head straight and looked at you with determination.

As much as Lydia was interested in him, she felt intimidated by him as well. And she was falling in love with him without knowing it.

She learned that Marcus had applied to the liberal arts track in school because he wanted to be a painter. He worked on large canvases in the Renaissance style of Raphael and Leonardo Da Vinci, and he showed them at school exhibits to his colleagues’ and teachers’ admiration. They all said he was a very good artist, but he was very good in every subject. His freshman year physics teacher, a person feared for his exigence and high standards, had objected to Marcus’s choice of programs. He wanted to keep the young man under his tutelage and develop his obvious aptitude for the sciences. Marcus dismissed his physics teacher’s pleadings, and, in his sophomore year, he won first place at the National Olympiad for Language and Literature.

Marcus resembled her deceased father, a writer, Lydia thought, in his creativity and passion. She would have wanted to tell Marcus that he reminded her of her dad, but that wasn’t a subject easy to breach, and she didn’t know how to approach him, or how to catch his attention. She wasn’t the only one admiring Marcus: boys and girls followed him everywhere.

While in school, they were all required to wear uniforms. The boys wore navy blue pants and jackets, white shirts, and grey ties; the girls wore knee-length navy-blue pinafore dresses over white blouses. The cheap fabric creased in the front and acquired shiny patches in the back. Fashionable, knee-high stockings were forbidden, as were long nails, polished nails, coiffed hair, jewelry, or makeup.

Marcus’s uniform was custom tailored out of a soft blue wool cloth he claimed had been imported from England.

With his yellowed shirt collar open and his tie hanging loose, Nick Lungu competed for attention with Marcus. They were equally tall, but Nick was lankier, less intense, less articulate, and more sensitive. Or at least he pretended to be. A mediocre student, he made a long face when receiving a bad grade, as if to suggest he had been misunderstood, as if it wasn’t his fault that he didn’t know the correct or the complete answer and the teacher was picking on him for no reason. His bright blue eyes would grow darker, his eyelashes would bat rapidly, his skin would lose color and he seemed on the verge of tears. Everyone understood his desire — indeed, determination — to become a drama actor. He auditioned for the most prominent roles in school plays and walked among his fellow classmates with the airs of a professional actor. He was handsome, with long dark hair combed sideways and a narrow face with red lips, round chin, and regular features. Girls loved him and clung to him at least as much as they loved and clung to Marcus, him being more down to earth and accessible.

When he came to school wearing American blue jeans under his uniform jacket, the principal sent him home for the day demanding that he comply with the dress code. “And get a haircut while you’re at it,” the principal requested. “They pretend not to see Marcus in his fancy British uniform, because his dad is a doctor,” Nick said to Lydia under his breath as if he had been singled out and discriminated against, yet happy at the opportunity of a free day in the city. “And what is wrong with my hair?” It was the late sixties, the Beatles had conquered the world, and long hair was fashionable. Nick’s mother, who was known to spoil him, tried to come to the rescue. She argued with the principal unsuccessfully and walked around the school speaking to anyone willing to listen. “What’s with these stupid rules and why should a sensitive soul like my son have to repress his outbursts of individuality?”

Nick Lungu was shallow, Lydia thought as she leafed through colorful fashion magazines from France and Germany. Together with Carmen and Nick, she went to see Natalie Wood starring in Splendor in the Grass. She saw The Last Adventure with Alain Delon, and later A Man and a Woman, with Anouk Aimée and Jean-Louis Trintignant. The way the people in the magazines and these movies looked, lived, loved, sang, and danced was appealing. It was different.

*

Lydia’s family received letters and parcels from people who had left Romania and now lived in different western countries. Her mother’s friends, Dora and Zoltan wrote from Rio de Janeiro. Lydia’s aunt sent chocolate from Basel, Switzerland. Their relatives from Israel, Miriam, Larissa, and Simon wrote regularly. The letters were a window on another world, their paper thin, crisp, and fragrant.

Opening the gift boxes was a family affair. They eagerly gathered around the dining room table and Lydia took the items out of the cardboard box one by one and handed them gracefully to the intended recipients. There were precious nylon stockings, soft underwear, beautiful blouses, shawls, cashmere sweaters, bracelets, silk ties, chewing gum, Lindt chocolates, and fashion magazines. Lydia adored Swiss chocolate. She liked the buttery smell and the fine silvery wrapping and how it melted between her fingers even before she placed the smooth chocolate in her mouth.

Lydia dressed well, albeit modestly. She had a nice figure and straight, shapely legs and outside school, she liked to wear miniskirts and nylon stockings or tight-fitting pants and happily displaying her new blouses and matching earrings from abroad.

Letters and packages also came from Dante, the boy Lydia had befriended in elementary school. He wrote first from Rome and then from New York. His family had emigrated to Italy, and later they moved to the United States. His letters were typed with an electric typewriter. He included colored pictures of himself, his straight blond hair combed over his ears. The boys in Lydia’s school would be jealous if they saw that hair. Dante wrote to her about his life in Queens and about becoming a taxi driver at 17, to earn some pocket money. He wrote to her about Peter, his new American friend and classmate, and the electric car they built together and their trip to California. Lydia had to look on a map to comprehend the extent of that journey.

In one parcel from Dante were several pairs of lacey, white knee-high socks, and she wore a pair to school. The principal suspended her for the day. Her friend, Carmen, was suspended as well because her jumper was too short. They spend the day at the school library doing homework and trying to forget how demeaning the school rules were. Afterwards they stopped at a small coffee shop. Carmen’s father had worked as a cultural attaché at the Romanian Embassy in Rome and Carmen had spent two years in that miraculous city. She told Lydia about the art she had seen, the churches and the monuments. Lydia mentioned her letters from Dante. Carmen was in love with Doru, a young man in their class, who, in turn, was in love with Liana. Lydia noticed that the romantic entanglements of her schoolmates were more convoluted and involved than in a Shakespearean comedy.

*

In tenth grade, Lydia started going to tea soirées, parties which were held in young peoples’ apartments when the parents were not at home. Music was loud and smoke billowed. Everyone smoked. They listened to French and American music and danced. They kissed. They necked.

The decree against abortions had been issued a full year earlier, in 1966. There was no birth control. Women died from back-alley abortions. Doctors and nurses went to jail.

With young men and women of school age the rules were simple: nothing below the waist.

One night Nick kissed Lydia. She didn’t think too much about it. Another night another boy kissed her.

Marcus did not come to these parties. He lived in a different universe. Lydia decided to overcome her perennial shyness: she found out where he lived and was determined to wait for him in the street and talk to him when he came out of his apartment building. She asked Carmen to join her. The first time they waited a full hour, and he didn’t show; the second time, when Lydia saw him, her legs started to shake, and the girls ran away. It was on the third attempt that Lydia stepped into Marcus’s path. They walked together to the street corner, talked for a few minutes, and parted.

Her face flushed, Lydia rejoined Carmen. “He agreed,” she said. “First, he said he didn’t want to date me because we go to the same school, but I told him I love artists. I told him I’m ready to sleep with him, and he nodded.”

Carmen’s mouth dropped open. “You didn’t.”

Marcus took Lydia to a friend’s empty apartment. They kissed and they touched each other. His body was rock solid. He started undressing her and impatiently tore off the nylon stockings she wore in an attempt to look sophisticated.

When he reached for her underwear, she stopped him.

He looked up. “I thought that’s what you wanted.”

“I’ve never done it before. What if I get pregnant?”

“That’s not my problem,” he said and looked down at his briefs stretched by his erection. “But if you’re still a child and all you want are half measures, then date Nick Lungu. Don’t waste my time. He is an artist, too.” He uttered the word artist full of disdain and cracked his knuckles. His fingers were stained with blue and red paint.

Lydia said no again.

He got dressed and silently left the apartment.

In school, he treated her as if they had never met, as if she didn’t exist. She hated his attitude. She understood and she didn’t. She watched Marcus strut around in class and in the hallway, and yes, sometimes her body reacted despite her mind. There was arousal and tingling. She felt the vague desire to surrender. Yet her mind was always there, a barrier. She avoided imagining what could have happened. In fact, even kissing had proven mechanical, perhaps because of her inexperience. There was tenderness and excitement, the hot breath in her face, the cigarette smell, the wet lips, and saliva. One day, with the right man, she would have real sex, but her time wasn’t now. There was so much more in the world that she had to discover. She loved the summers at the beach, with the sun and the water. She loved the mountains. An acquaintance lent her a forbidden copy of Doctor Zhivago in French, for 48 hours. She rushed through the almost 600 pages, touched forever by the story of Yuri and Lara. She enjoyed her older cousin Galina and her husband Ghiță’s disarming banter about buying this and that for their new apartment. Her stepfather took her to his darkroom and taught her the basics of developing film and photos.

Most of her friends dreamed about leaving the country. They spoke about Paris and London, about the Sorbonne and Heidelberg. New York was a magnet.

*

Lydia didn’t know what she wanted. She didn’t know what life had in store for her or for any of the people around her.

She didn’t know that the Soviets would invade Czechoslovakia the summer before her senior year and that she, on her stepfather’s advice, would stay home surrounded by books rather than respond to the call of the voluntary Patriotic Guards taking shape all over the country.

She had no idea that one year later, Marcus Diaconu would be admitted to the Romanian School of Fine Arts, become a well-known painter, defect to Switzerland, gain international fame, and dye of cirrhosis of the liver at age 39.

She didn’t know that Nick Lungu would follow the Bucharest Drama School, act in a number of commercially successful Romanian movies for which he would acquire the reputation of a Romanian Alain Delon, sleep with countless women, marry and divorce two of them and die in a Bucharest slum with an empty gin bottle in his hand.

Carmen would never succeed in stealing Doru from Liana, never marry, and, after studying Art History, would end up working for a meager income as a specialist in Greek and Italian Arts at the Institute of Cultural Studies.

Dante would receive a Master’s in Electrical Engineering, meet an Italian American woman one inch taller than him through a dating service, and start a family with her in Danbury, Connecticut.

As for Lydia herself, the wide and beautiful world around her would become her playground, without artists, but with plenty of love, chocolates, and nylon stockings.

[image error]November 7, 2021

A Walk in the Garden of Eden

Găești, 1964

From A Family Album: https://alexduvan.medium.com/a-family-album-40829e212764

To attend one of the best schools in Bucharest, Carmen lived with her grandmother in the old house in the city. Her parents were doctors and worked at a hospital in Găești, a small town one hour away. Commuting was too much of a hustle and they had rented a place in Găești, and saw Carmen only on weekends.

The summer before seventh grade, Carmen invited her best friend Lydia to spend a week at her parents’ “country” house. On Monday morning, the girls, Carmen’s grandmother and her parents boarded the commuter train to Găești. The train stopped in all the hamlets and villages on the way, falling behind schedule. Carmen’s parents had to report to work, and the delays made them nervous.

At one stop, the girls saw a large crowd of Gypsies on the pier. New, six-story apartment buildings rose behind the train station.

“Our farm and our orchard used to be where those buildings now stand,” said Laura, Carmen’s grandmother. She was a large woman who always dressed in ill-fitting, baggy clothes. Her chin-length white hair floated around her head like a sail. “Then the government took them over and destroyed them. Good thing we still have our name, and our old friends in Găești helped Klaus and Dorina. Because they are not party members and they couldn’t find work in Bucharest.”

They were alone in the compartment. Still, Klaus raised a finger to his lips. “Hush. Not again. Not on the train, mother.”

“Why not? Let the girls know. The government took everything.”

Carmen rolled her eyes in mock annoyance. She had heard her grandmother before.

Not interested in pursuing the discussion, Klaus turned to Lydia. “A year ago, the government launched a program to integrate and civilize the Gypsies. They were moved from their tents into the apartment buildings behind the station. For free.” A smug smile appeared on his face. “What you see is the result. The Gypsies brought their animals with them and pitched their tents in between the buildings. They slept in the open, and let the pigs, the chickens and the goats live inside the apartments. There is nothing for them to steal in this hamlet, and they assault each train, trying to make it to Bucharest without tickets.”

Lydia had seen Gypsies in downtown Bucharest, in small and colorful groups, the men staying back and watching as their women and children approached pedestrians and begged. The passers-by would speed up, making sure they didn’t lock eyes with the Gypsies and tightening the grip on their own children.

Now, another train arrived from the opposite direction and the Gypsies seemed to be thrown into disarray. They yelled, pointing at the different railcars, and trying to board them. The conductors pushed them away. A woman in a black, red and green wrap-around shawl, holding a child with each hand, ran in one direction and then the other. A man with a green fedora hat carried a large accordion on his back. Ignored and forgotten, a toddler sat on the concrete ground, waving his arms, and screaming. He had no shirt, and tears ran down his face tracing narrow channels through the soot and dust that covered his cheeks.

Lydia knew from her mother that the Gypsies had always been discriminated and even sent to the death camps by the Nazis. Lydia’s mother was a member of the communist party and worked in Bucharest. “The communist regime treats all people equally,” Lydia said. “We’re all human beings.”

“You can’t help those who don’t want your help,” said Dorina.

“They subdivided our beautiful house in Bucharest and gave the upstairs to a carpenter and his family,” Laura continued as if Klaus had not stopped her earlier. “You know, where Carmen and I live now, in two small rooms and the kitchen. My husband was so upset, he died of a bad heart two years later.”

The train moved and Lydia looked again out the window. “Every person deserves to be happy,” she whispered, her mind still on the Gypsies.

“They live in the past,” Carmen told Lydia later, when they arrived in Găești and walked a few steps behind her parents and grandmother. “I hope you don’t mind them.”

*

Their rented house stood on Main Street. It was a single story brick building with a tall wooden fence and a large backyard. In one specially outfitted room, Dorina attended after hours to women who required services not provided by the hospital. Their good name notwithstanding, that separate income exceeded their hospital salaries, and helped the entire family enjoy a more comfortable living.

The parents rushed to the hospital, and Laura told the housekeeper to make the girls some breakfast. She didn’t touch the food, and stood by the large window overlooking the garden.

“Why don’t you eat with us, Grandmother?” asked Carmen.

“I’m not in the mood.”

“Then I won’t eat either.”

“You must eat,” said Laura. “You girls need to put some meat on you. Sticks alone don’t attract anybody.” Then she added, “Look at the poppies how they sway in the summer breeze. They remind me of your grandfather.”

“He died over ten years ago,” Carmen said. “Honestly, I don’t even remember.”

Laura retrieved her purse from the back of a chair. “Here is a picture of him,” she said and handed the girls a small black and white photograph. “My prince charming.”

“You showed this to me many times,” Carmen said. “Spend a few days in Găești with us, and you’ll get over these melancholy feelings. Why do you have to go back in the early afternoon? Why the hurry?”

“You know why,” Laura said and pulled at her white hair. “Someone has to keep an eye on the house. When I’m away, the carpenter and his family break things, and then they complain. Truth be told, they behave like animals.”

Carmen shook her head in disbelief. “They’re not that bad. I know. I live with you, Grandma.”

Laura walked back to the window. “Lydia, you should have seen our orchard,” she said in a softer voice, looking outside. “It was paradise, really. In the early spring, the apple blossoms bathed you in their fragrance. Peasants who picked the fruit in the summer collected bushels and bushels. A brook ran though the valley, its water like crystal. When the leaves turned in the fall, they looked like golden rainbows.”

Behind Laura’s back, Carmen made faces.

“Carmen, you can laugh all you want,” Laura said. She appeared to see everything. “When we were together, your grandpa and I, life was beautiful. Love was beautiful. Those were our times. After he died, I thought I was done with this world, but you came to stay with me, and you saved me.”

“I love you, Grandma,” Carmen said, and she smiled at Lydia. “I hope my prince charming is somewhere out there.”

“He will be, my dear. Just you wait a few years.”

“Yes, Grandma. Don’t let me bite from the forbidden apple too early, or I’ll be chased out of your Garden of Eden.”

“Here you are, making fun of me,” complained Laura.

*

As soon as Laura left for the train station, Carmen pulled a folded piece of paper from a book in her satchel and handed it to Lydia. The paper smelled of rose water. “These are the boys I kissed,” she announced proudly. There were five names written neatly in blue ink, one under the other. A sixth one — Marcus — stood apart, in red, at the bottom.

“Is Marcus special?” asked Lydia.

“He’s nineteen and he knows how to kiss.”

Lydia had never kissed a boy in her life.

The housekeeper came in and cleared the table. Carmen opened the window to let in the fresh air. She closed the door to the kitchen, listened for a few seconds to make sure they were alone, and surreptitiously produced a lighter and a cigarette that they shared.

*

The days went by quickly. Carmen and Lydia were happy together, in a world that seemed limitless and without obligations. Boys were on their minds, like shadows. They talked about them as they took long walks through the village streets, and while they sat side by side in the living room with books in their hands pretending to read.

Carmen showed Lydia her insect collection: beetles, butterflies, and crickets she had caught in the backyard, pinned onto a large piece of cardboard in a flat box under glass. They went out to catch more insects. Lydia wielded the net. Carmen grabbed the specimens and placed them in a jar. When they returned home, most insects were dead, except for a butterfly that kept flapping its wings with a languid sadness.

Lydia looked at it tenderly. “Happily flying a few minutes ago, almost dead now. No one knows what the future brings.”

“Do you want to know how you’ll die?” Carmen asked and inserted the needle through the butterfly’s thorax.

“Not how I’ll die,” Lydia said. “But I would love to have an idea of what’s in store for me in the future.”

“Then let’s go and find out,” said Carmen and pushed the insects aside.

“Go where?”

“You’ll see. And bring some money.”

They walked fast, first on Main Street, then on a narrower street with houses tucked back behind old trees, then across an old park overgrown with weeds and finally through a muddy lot, with flimsy wooden shacks dropped there haphazardly as if blown around by the wind. A few children were playing in the mud between the shacks, while several young women with long dark hair and flowing dresses sat on their stoops, talking to one another in harsh tones and looking bored.

“Gypsies,” Lydia mumbled under her breath.

Carmen nodded and raised her hand. “We’re looking for Mama Matilda,” she said to no one in particular.

“Who should I say is calling?” one of the young women asked.

“We’ll tell her who we are. Just take us to her.”

The woman walked into the shack behind her and reappeared with a silver amulet in one hand and a small leather purse in the other. “Go right in,” she said, “but first pay.” And she specified a number.

“That’s twice the rate,” Carmen said. Lydia didn’t wait and counted the money. Greedily, the woman grabbed the money and shoved it into her purse. Then she handed the amulet to Lydia. “I stay here to watch my sons, but you go in. Give this to Mama Matilda and she’ll know who you are and that you paid me.” The woman smiled for the first time and Lydia noticed deep dark shadows floating under her eyes. She could have been Lydia’s age, or younger.

Inside, it smelled of incense and the windows were covered by drapes. A shadow rose from the sofa and came forward. Lydia extended the amulet. The shadow took it and pointed to a chair. “I’m Mama Matilda. Lydia, sit down,” she said in a cavernous voice. There were only two chairs, and Mama Matilda took the one opposite Lydia. “Carmen, I know you don’t want me to tell you the future. Not today. But if you’re curious to hear Lydia’s, pull up a chair and stay. If not, wait outside with the children.”

Carmen nodded. “I’ll stand.”

There was a small iron stove to Mama Matilda’s left. The stove door was open, and even though it was summer, a flame burned inside. The light from the fire came and went. Mama Matilda took Lydia’s hand and turned it with the palm facing up. She dragged her thick nail along her lifeline. “It’s well defined. You’ll have a long and good life,” she said. The fire illuminated her face. Her fine features resembled the young woman outside. She was older, but not by much — her older sister or her mother. She wore gold loop earrings. “The best way to tell someone’s future is to read it in my tarot cards.”

Lydia shrugged.

Mama Matilda placed the amulet on the table and inserted her hand in the pocket of her dark, overflowing robe. The exact color of the fabric was hard to distinguish; yet the fabric seemed silky and soft. Her bare forearms were covered in silver bangles. She pulled out a deck of cards. “Cut” she said, and Lydia obeyed.

Mama Matilda laid out six cards, then three more. She picked up the amulet and moved it over the cards in a slow, continuous motion, after which she turned the cards face up. “This is very unusual,” she rumbled. Lydia leaned forward to understand what she was saying. “In the first nine cards you pulled five from the Major Arcana: the Magician, the Lovers, the Wheel of Fortune, the Temperance and the World. This tells me you will be loved. You will return love. Your man will have dark hair and green eyes and will take you to a far away land across the ocean. You’re truly blessed, my young friend. Be happy.” As Mama Matilda said the last words, she shook her head sideways and a strand of hair, bright orange like the fire, disengaged from her otherwise charcoal black hair and fell over her forehead.

“How did she know my name?” Lydia asked after they left Mama Matilda.

“She’s a psychic,” Carmen said.

Lydia didn’t seem too convinced. They were walking fast, approaching Main Street. “And why didn’t you want her to tell your future?”

“Because I know it.”

*

“His father is my dad’s cousin, and the entire family visited us in Găești. That’s when I met him.” Carmen took Lydia’s arm and led her along the white gravel path in the backyard.

“Who are we talking about?” asked Lydia.

“Marcus, of course. Marcus. He’s the one who’s on my mind day and night.”

“Tell me about him,” Lydia said, emboldened by what she had learned form Mama Matilda.

“We were bored stiff,” Carmen said. “After dinner, I suggested we go for a walk. It was still early. He lives at home with his parents and studies architecture. You should see his hands. He’s an artist.”

“I like hands with long fingers.”

“Yep, his are really long. And his eyes are very expressive. We escaped from the family and went to the forest. We carefully skirted the swamp fed by the brook that passes through our backyard, but I know where the dry trail is. The trees are old and large, and it can get dark and confusing. I’ll take you there tomorrow. After a while, you get to a clearing. Marcus and I sat down in the tall grass to rest. And I kissed him.”

Lydia stopped walking. “You did?”

“Why not? He’s the son of my father’s second cousin, so we’re not related. No incest to worry about. Nothing.”

“I didn’t mean that.”

“I was sure he liked me. He put his arm around my shoulders and kissed me back, and I swear, it lasted several minutes. I was all glued to him and he pushed his tongue into my mouth.”

Tall marigolds and daisies bloomed on both sides of the path where they stood. In the hot afternoon the flowers seemed sensual.

“Tongue,” said Lydia.

“Yes, tongue. Ask anybody. That’s what you’re supposed to do when you’re kissing.”

Lydia started walking again and the further they walked, the wilder and thicker the flowers became. “Then?” Lydia prompted her friend. She was very curious.

“Then we laid in the grass, and he placed his hand inside my bra. He slid his other hand under my dress and touched me. It was as if an electric current shook my body. Oh, Lydia, that moment! I was so tempted but I hesitated. No, I mumbled, and he didn’t react, so I pushed him aside. He seemed surprised and looked at me breathing heavily. I said no again, and he rose to his feet, disappointed. ‘How old are you?’ he asked staring at me from above and he huffed when he heard my answer. ‘I should have known,’ he said. ‘This is going nowhere.’ ‘Marcus,’ I said, ‘I like you.’ ‘I liked you also,’ he answered and walked away. ‘Marcus,’ I yelled after him. When I got home, he was sitting on the steps, waiting for me. He had walked through the swamp and his pants were soaking wet and his shoes were all muddy.”

The girls laughed. Where the brook crossed the backyard, tall reeds swayed in between the marigolds. Weeds peeked through the gravel.

“So, this is the story of Marcus,” Lydia said.

“The beginning of the story, trust me.” Carmen’s cheeks turned rosy. “What comes next is my future. I’ll tell you, and you shall know it. I love Marcus, I’m certain. I called his house a few times and left messages. Maybe his mother didn’t deliver them to him on purpose. But I know where he lives and if I don’t hear from him, I’ll go there and face him. It will be an ambush. You can come with me if you want.”

“What will you tell him?”

“That I had time to think this over, and this is our time. I’ll tell him I’m ready.”

“Ready for what?”

“Oh, my God, Lydia, are you that innocent or are you stupid?”

“Carmen,” Lydia yelled and grabbed her friend’s shoulder.

“What?”

“Turn around. Slowly.”

A snake, thick as Carmen’s forearm, slithered off a boulder onto the path behind them and raised its head hissing.

[image error]October 30, 2021

The Girl in the Center of the World

Bucharest, 1958–1962

From A Family Album: https://alexduvan.medium.com/a-family-album-40829e212764

Lydia and her parents moved into an apartment a few hundred yards from Roman Square. “That’s in the center of everything,” Lydia’s father said.

Before they moved, Lydia had to ride bus number 37 to school. She attended the German School because it had an excellent reputation, and because her grandmother, who lived with them, spoke only German at home. Worried about safety, her grandmother accompanied Lydia everyday on the bus.

The school was close to the town center. Many of Lydia’s classmates lived nearby. After the move, Lydia walked to and from school together with them, and she could visit them after classes. Her grandmother stayed home.

The streets were crowded — a monochromatic gray image painted with broad strokes. There were gray cars, people in gray overcoats, and long lines at the stores. Her friends’ apartments, in old, gray high-rise buildings were crowded and small.

In third grade, her friend Frantzi and his family were allowed to leave Romania. Principal Gerhardt walked into the classroom and interrupted the teacher. “Francis Gruenberg,” he said. “Your mother is here and you’re going home.” Frantzi rose and silently gathered his stuff. The children fidgeted and Principal Gerhardt continued. “The Gruenbergs are being reunited with their family in Düsseldorf. We hope that the crumbs of German culture we have taught Francis in our school will benefit him, and we all wish him the best of luck in his new endeavors.”

Their teacher clapped. The children followed her lead and clapped as well. Frantzi was tall and fat andstood at attention.

“After what the Germans did, it’s astonishing they’re choosing Germany. Jewish people like us should go to Israel, if ever permitted to leave,” Lydia’s father said.

“They should stay put,” Lydia’s mother said. “Leaving our country is not what we should do.”

*

Simona was a quiet and slender girl with brown eyes and Lydia enjoyed talking to her during breaks. Her last name was Matti. Double consonants were rare in Romanian names and indicated a foreign origin. Simona’s father was German. On that basis, Simona qualified to attend the German School. The two girls spoke German and Romanian interchangeably. Like Lydia, Simona was an only child. She lived with her mother and father in a two-room apartment near Galați Square. In fifth grade, Lydia learned that Galați was the name of a town. She also learned that our planet was round — not round like a circle, but like a sphere. She had a hard time visualizing that.

It took Lydia the same time to walk from Roman Square to Galați Square as she needed to walk to her school. If Roman Square was in the center of everything, then her friends’ apartments were dots on the spokes of a wheel.

In sixth grade, in the biology lab, which was full of potted exotic plants and stuffed birds and small mammals, Lydia was seated near Cora, a girl with an aquiline nose and thick glasses. “We Jews must stick together,” Cora whispered into Lydia’s ear before the class ended. Lydia wasn’t sure what Cora meant. Cora’s last name was Kadosh, which sounded both foreign and funny. Lydia had seen her many times before, but didn’t remember ever speaking to her, much less mentioning her religion, and Cora’s words had the feel of a conspiracy between the two.

One day before Christmas, Marcel, her neighbor who was Lydia’s age but didn’t go to the German School, told Lydia that the Jews killed Jesus. That sounded to Lydia like a conspiracy, too.

Dante Codrescu sat in the back of the class with the unruly kids. He was unruly but likable. His body was narrow and straight like a board and his hair had the color of wood. He was rumored to be a genius of sorts. From the second grade on, he could multiply two-digit numbers in his head. He understood percentages. His mother was Italian, so he spoke Italian, as well as Romanian and German. His father was of German extraction, from a small town in Banat. Like many others, he must have changed his name to better fit in. The father owned a machine shop, which was rare — private businesses were frowned upon.

Dante built a metal rocket half a meter in length, which used celluloid film as fuel. His idea was that the energy developed by the burning film would propel the rocket straight up, to a high elevation. Simona and Lydia came to witness the experiment. Dante asked them to stay back. Black smoke and flames roared from the exhaust chamber. The rocket rose one meter, veered, and fell backwards into the shop. Papers and rags caught on fire. It took Mr. Codrescu two weeks to clean and repair the walls.

*

It was late winter when Dante stopped coming to school. Lydia didn’t know why.

Walking home, when boys saw an ice patch, they challenged each other and ran towards it, gaining enough speed to skid, one foot forward as rudder, arms flailing, scarves flying, steam puffing out of their noses and from between their lips. Their heavy backpacks bounced on their backs. Pedestrians complained they were making the sidewalks slippery, but the schoolboys couldn’t care less.

Lydia was walking home with Simona when Dante appeared at the top of her street. He wasn’t running or skidding on ice. He was tense. His hands were clad in heavy mittens. A Russian fur hat covered his forehead and his ears and an inverted sheepskin jacket with large, bulging pockets kept him warm. “Hi. I’m glad I caught up with you,” he said.

“Dante!” Simona exclaimed.

“Where have you been?” Lydia asked. “Why aren’t you in school anymore?”

He told them he wanted to bid his farewell. He was leaving the next morning with his mother and father to Udine, in Italy, where his maternal grandmother lived. He was leaving for good. He didn’t want to see all the kids in his class — he didn’t have much patience left — but he wanted to see his two friends. “You have meant a lot in my life,” he said.

The girls blushed.

He took a step back. “I’ll write to you,” he added looking at Lydia. Then he turned on his heels and took off.

“He thinks he’s important,” Simona said.

*

Three months later, Lydia received Dante’s first letter. The airmail envelope had red and blue stripes along the edges. Two translucent sheets of paper were covered in Dante’s hurried handwriting. Lydia had never seen paper that thin.

Rome, April 21, 1962

Dear Lydia,

By now the snow must have melted in Bucharest and you must be enjoying the soft April sun. Being farther south than you, spring has arrived here earlier. It is warm during the day and flowers are blooming everywhere, but don’t ask me to describe them to you, because I will stumble. As you know, I am dedicated to inventing and building, not admiring nature, although, from time to time, breathing fresh air can be nice. If I miss anything, it’s my father’s workshop and the ability to play with his tools. For sure, I enjoy not going to school. Without denying the value of a good education, I believe that school is overrated, invented by adults to rid themselves of their pesky children and confine them to a monotonous and well-controlled environment. I’ve learned more in these three months of travel than in all my school years combined.

But let me start from the beginning. We left Bucharest that evening in February and traveled all night by train to Timișoara and from there to the Yugoslavian border. My mother worried about the border crossing. She had heard horror stories about people being searched by customs officials, ordered off the train and even arrested on fake charges and separated from their traveling companions. My father and I tried to convince her otherwise, but even after we crossed without an incident, my mother continued to be nervous until we arrived at our destination.

In Udine, we met Nonna, which is how I call my grandmother in Italian, and I liked her. I liked her a lot.

She has an old stone house, and she gave us the upper floor, comprised of a large bedroom for my parents, a smaller one for me, and a separate day room, more space than we ever had in Bucharest. The walls are cracked and measure one meter in thickness. You smell mildew as soon as you enter the house.

I met my cousins twice removed, two boys my age, Luca and Fontini, but I didn’t like them. My problem with them was that we spoke and spoke but we rarely agreed on anything. It seems to me that in Bucharest the communication between people was generally more efficient, or maybe I was too busy with school and what have you to pay much attention. In Udine, my saving grace came in the form of a barn in Nonna’s backyard which, guess what, holds an abandoned Fiat. I couldn’t believe it! The moment I saw the car I wanted to restore it, although doing that was useless since it would take a few months of work, and in the end I would be too young to drive it. Father came down to help — I guess he was itching for something to do as well — and he looked around and stuck his head under the hood and picked up the pliers. The great thing with my father is that we don’t need to say anything to understand each other.

Udine turns out to be a quiet provincial town with an old square (Piazza della Libertà) with its town hall and a clock tower, which, they say, resembles the one in Piazza San Marco in Venice. I hear that Venice is remarkable and as soon as I make some of my own money, I’ll be sure to visit.

After a few weeks, my father decided to leave Udine, a nothing place where no one could start a business no matter how much money Nonna was willing to invest with us, and, over Nonna’s tears and my mother’s opposition, he packed our luggage, and we boarded the train to Rome.

Now Rome, this is a city! Lydia, I can’t even tell you how many things one could see here. How much history! Our lodging is not as comfortable as in Udine — we share a small room with a small kitchen — but I don’t care. My mother bought a city guide and every day the two of us go visit some marvel that leaves us awed and speechless: the Vatican, the Coliseum, the countless churches, the ruins and, as diligent Romanians, Trojan’s Column with its bas-reliefs depicting scenes from the Roman conquest of Dacia. I’m glad they did it, because this is why Romanian is so similar to Italian.

School is out of the question until the fall, which is perfect.

Father is looking for a job or a business opportunity, most likely in a car repair shop. Boy, you wouldn’t believe how many cars you see here! They are driving like crazy and sometimes I feel like the world is spinning around me.

Well, I think I must stop here, because otherwise I’ll start describing Rome to you and I’ll never finish.

If my dad opens his garage — because that’s what I want him to do — I’ll work there and with the money I’ll make I’ll buy myself a typewriter. Expect typed letters from me in the future, with more information about me and especially about Rome. Please write back soon.

Your best friend,

Dante

On her desk, Lydia had a globe of the earth. She turned it until she located Rome. She found Bucharest next, which was not represented by a circle, but a dot, and she wondered about the connection between the Roman Square and the city of Rome. Then she looked for Dusseldorf, which must have been too small because it wasn’t marked on the globe. Finally, remembering her father talking of a country for the Jewish people, she searched for Israel. Israel was very small, much smaller then West Germany, which, Lydia knew from school, was half of what Germany used to be. The entire area she looked at was small, compared to the overall globe. She drew imaginary lines from Bucharest to Dusseldorf, to Rome and to Tel Aviv. She saw how her circle had widened and how much more it could grow. Someday, she too would fly out and travel the world.

[image error]