Brian Tice's Blog: Halakhically and Hashqafically Historical

February 26, 2022

Reading Rashi

Rabbi Shlomo Itzhaki, aka Rashi, is known for his literal approach to Scripture exegesis. His commentary on the Torah is included in nearly every medieval and post-medieval chumash, usually written in a specialized script which has come to share his name. Rashi's Commentary format addresses specific glaring questions in the Torah's text:

1. Clarifications: when words, ideas or events are hard to understand, Rashi explains them.

2. Contradictions: when verses seem to contradict each other, Rashi aligns them.

3. Superfluities: when words or ideas seem redundant or repeated, Rashi distinguishes them.

4. Juxtapositions: when seemingly unrelated themes are next to each other, Rashi relates them.

5. Deviations: when the Torah's grammar rules seem to be broken, Rashi rights them.

6. Disparities: when the words change from the norm, Rashi explores the reason(s).

January 8, 2022

Shabbat: To Remember and to Observe

Our rabbis share that zachor - remember is different it it’s nature than shamor - observe. Observing Shabbat means that we abide by the 39 malakhot (Sabbath prohibitions), whereas remembering Shabbat connotes the positive mitzvot of singing, praying, studying (spiritual delights); and challah, kiddush, and community (physical delights).

Our tradition to light two candles as we enter into Shabbat is associated with this - one candle l'zakor (to remember) and one lishmor (to observe).

Choter ben Shlomo summarizes these obligations thus: "The actions that are permitted on Shabbat are bowing and the motions which attend food, drink, common actions, and rest; the actions which are forbidden are riding an animal, climbing a tree, writing, running, dancing, and striking... [These are also permitted:] to comfort the bereaved, a circumcision, to visit the sick, or anything connected with charitable deeds" (Siraj al-Uqul 85b). The turbidity and coarseness that coalesces in the soul during the week is cleansed and purified through our worship and rest on Shabbat.

Shabbat shalom!

November 26, 2021

Sofrut Articles on Sefaria

https://www.sefaria.org/profile/brian-tice.

November 23, 2021

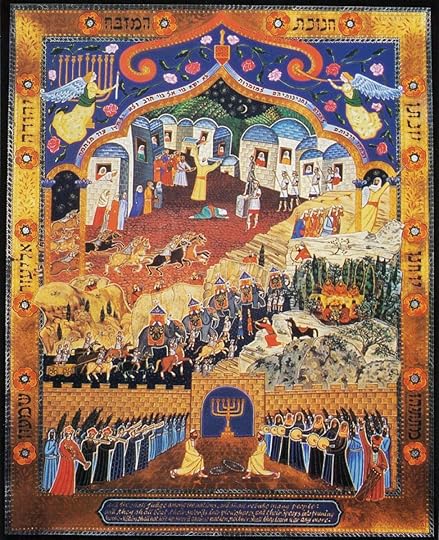

Historical Accounts of the First Chanukah

As we approach Chanukah, let us discuss the sitz im leben (historical backdrop) of the Judaism of that era, up to and including 164 BCE. Within Judaism, there was a tension between the traditionalist Jewish element and those who had come under the allure of Hellenism. The Maccabees, who led the rebellion against Seleucid (Greek) Emperor Antiochus Epiphanes IV, were ironically of the more Hellenized sect - the Hasmoneans.

As we approach Chanukah, let us discuss the sitz im leben (historical backdrop) of the Judaism of that era, up to and including 164 BCE. Within Judaism, there was a tension between the traditionalist Jewish element and those who had come under the allure of Hellenism. The Maccabees, who led the rebellion against Seleucid (Greek) Emperor Antiochus Epiphanes IV, were ironically of the more Hellenized sect - the Hasmoneans. "1 Maccabees" is written from the Hasmonean (Hellenized) viewpoint, praising the Greekness of the "new Judaism," with no mention of Hashem in the account. "2 Maccabees," in contrast, tells of the same events from the Traditionalist Jewish perspective, pointing out where Hashem was active in the revolt and calling for a turn away from pagan Greek influence and a restoration of "genuine" Jewish nusach/liturgy. "The Wisdom of Solomon" also speaks of this tension in the Judaism of that time period.

Josephus, writing after the extinction of the Sadducean and Essene sects, surmises that the Essenes' departure from mainstream Judaism is a reaction against the Hasmonean merger of the political and religious roles into a single head, i.e. a longing for a return to a more proper "true" priesthood. Some opine that the Yachad community of Qumran was Essene (others see it as a non-Essene separatist community).[1]

It is worthy of mention that the miracle of the oil which is so central to our modern Chanukah celebrations is glaringly absent from both of the aforementioned books of Maccabees.[2] The tradition of lighting the Chanukkiah's candles each day of the festival began more as a celebration of the Ancient Greeks’ failure to “pull Jews away from Judaism” and force us to “accept Greek culture and beliefs.”[3] We do get the miracle of the oil transmitted to us via the Oral Torah, i.e. Talmud Bavli, Masekhet Shabbat 21b (ca. 5th century CE). This is admittedly several centuries after the event, but the source whence it comes preserves an oral tradition which predates the written version by many centuries, so specifically when this element of the story became associated with it is uncertain.

The reason for the festival being eight days in length is probably less associated with the miracle of the oil and more owing to the fact that the Maccabean Revolt concluded too late for the celebration of Sukkot. The first Chanukah (Feast of Dedication) was actually a modified Sukkot festival, delayed due to Jewish worship having been outlawed prior to the revolt. Since Sukkot lasts 8 days, so also did that delayed observance of it which came to be the annual festival of Chanukah.[4]

_____

Notes

1. Jean-Pierre Isbout, "The History and Archaeology of the Bible" (Fielding Graduate University, 2021), course lecture 16.

2. Malka Zeiger Simkovich, "Uncovering the Truth about Chanukah," The Torah (n.d.; online: href="https://www.thetorah.com/article/uncovering-the-truth-about-chanukah).

3. Shayna Zamkanei, "The True Story of Hanukkah Is Not The Miracle of Oil; It’s Something Far More Insidious," Forward (12 Dec 2017; online: https://forward.com/life/389855/the-true-story-of-hanukkah-is-not-the-miracle-of-oil/).

4. Noam Zion, "The First Hanukkah: It was actually a Sukkot Celebration," My Jewish Learning (n.d.; online: https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/the-first-hanukkah/).

*The image used in this article is a Chanukah mural from the Magnes Collection of Jewish Art (Israel).

November 19, 2021

Whirled Pehs in Sifrei Torah

Focusing on the first in the list, the V'shamru, he writes that the peh of וינפש (vayinafash; "and He was refreshed"), which is pictured here (see the bottom left corner word) is "doubled" (a small peh written inside the proper peh) in order to emphasize the extra soul that we receive on Shabbat (ref.: b. Beitza 16a), as the root of וינפש (vayinafash) is נפש (nefesh; i.e., soul).

[image error]

This is what is said in b. Beitza [4]: "As Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish said: The Holy One, Blessed be He, gives a person an additional soul on Shabbat eve, and at the conclusion of Shabbat removes it from him, as it is stated: “He ceased from work and was refreshed [vayinafash]” (Exodus 31:17). Rabbi Shimon ben Lakish expounds the verse as follows: Since he ceased from work, and now Shabbat has concluded and his additional soul is removed from him; woe [oy vey] for the additional soul [nefesh] that is lost."

Nota bene: The image posted here comes from a Polish Sefer Torah. We know this due to the tradition visible here of placing an extra space between pasukhim (verses), i.e. two letter spaces rather than the single letter space normally placed between words.[5]

_____

Notes:

1. As described in Sefer Tagin (ספר תאגין): An Ancient Sofer Manual (ca. 2nd c. CE).

2. The "V'shamru" is often included in the weekly Shabbat liturgy. It is comprised of Exodus 31:16-17, i.e. the last 4 lines of the petuchah paragraph in the photo.

3. Baal haTurim, Commentary on Parshat Ki Tisa 31.17 (early 14th c. CE).

4. Gemara of Talmud Bavli (6th c. CE).

5. Yemenite scribes do this as well, to facilitate the tradition of reading each verse first in Hebrew, then from the Aramaic Targum (Onqelos), and finally from the Judeo-Arabic (Tafsir Rasag). By placing extra space between verses, it is easier to find the verse breaks and transition to the targumic texts.

November 16, 2021

Textual Variants within the Tefillin shel Rosh

Mathematically, there are 24 possible ways to arrange four different texts. Applying the halakha presented in the sources given to us in the texts included in this compendium reduce the possibilities to four and, not surprisingly, all four options have notable proponents. Many don both Rashi/Rambam and Rabbeinu Tam tefillin, and the last Lubavitcher Rebbe donned all four shitot (versions).

Rashi & Rambam: [1] kadesh li, [2] vehaya ki, [3] Shema, [4] vehaya im shamoa

Rabbeinu Tam: [1] kadesh li, [2] vehaya ki, [3] vehaya im shamoa, [4] Shema

Shimusha Rabba: [1] vehaya im shamoa, [2] Shema, [3] vehaya ki, [4] kadesh li

Ra'avad: [1] Shema, [2] vehaya im shamoa, [3] vehaya ki, [4] kadesh li

The tefillin found at Qumran (site of the Dead Sea Scrolls), over two dozen scrolls in total, are not helpful in resolving this makhloket as they do not match any of the above traditions. The order in one set (left) is [1] kadesh li, [2] Shema, [3] vehaya ki, [4] vehaya im shamoa (not original; a Beduin seller, apparently supposing that vehaya im shamoa belonged there, supplied it post facto). Three sets from Cave 4 bear texts which were not among the passages prescribed in the Talmud. One scroll was found containing Exodus 12:43-51, 13:1-10 (kadesh li), and Deuteronomy 10:12-19; another presents Deuteronomy 5:22-33, 6:1-3, and 6:4-6 (Shema); and on a third is inscribed Deuteronomy 5:1-21 and Exodus 13:11-16 (vehaya ki). In another set, the portions were removed before the order could be documented. It is worthy of note, however, that the sects associated with Qumran, i.e. the Yachad and the Damascus Covenant community, were non-normative communities, so any traditions found there which deviate from later Judaism might also have been aberrant with regard to normative Judaism of the Second Temple Era.

The tefillin found at Qumran (site of the Dead Sea Scrolls), over two dozen scrolls in total, are not helpful in resolving this makhloket as they do not match any of the above traditions. The order in one set (left) is [1] kadesh li, [2] Shema, [3] vehaya ki, [4] vehaya im shamoa (not original; a Beduin seller, apparently supposing that vehaya im shamoa belonged there, supplied it post facto). Three sets from Cave 4 bear texts which were not among the passages prescribed in the Talmud. One scroll was found containing Exodus 12:43-51, 13:1-10 (kadesh li), and Deuteronomy 10:12-19; another presents Deuteronomy 5:22-33, 6:1-3, and 6:4-6 (Shema); and on a third is inscribed Deuteronomy 5:1-21 and Exodus 13:11-16 (vehaya ki). In another set, the portions were removed before the order could be documented. It is worthy of note, however, that the sects associated with Qumran, i.e. the Yachad and the Damascus Covenant community, were non-normative communities, so any traditions found there which deviate from later Judaism might also have been aberrant with regard to normative Judaism of the Second Temple Era.

November 13, 2021

Sabbath in the Scope of Messianic Hope

תִּכַּנְתָּ שַׁבָּת רָצִיתָ קָרְבְּנוֹתֶיהָ. צִוִּיתָ פֵּרוּשֶׁיהָ עִם סִדּוּרֵי נְסָכֶיהָ. מְעַנְּגֶיהָ לְעוֹלָם כָּבוֹד יִנְחָלוּ. טוֹעֲמֶיהָ חַיִּים זָכוּ. וְגַם הָאוֹהֲבִים דְּבָרֶיהָ גְּדֻלָּה בָחָרוּ. אָז מִסִּינַי נִצְטַוּוּ עָלֶיהָ. וַתְּצַוֵּנוּ יְיָ אֱלהֵינוּ לְהַקְרִיב בָּהּ קָרְבַּן מוּסַף שַׁבָּת כָּרָאוּי.

יְהִי רָצון מִלְּפָנֶיךָ יְיָ אֱלֹהֵינוּ וֵאלֹהֵי אֲבוֹתֵינוּ. שֶׁתַּעֲלֵנוּ בְשִׂמְחָה לְאַרְצֵנוּ וְתִטָּעֵנוּ בִּגְבוּלֵנוּ

"You established the Sabbath; found favor in its offerings; instructed regarding its commentaries along with the order of its showbreads. Those who delight in it will inherit eternal honor, those who savor it will merit life and also those who love the speech that befits it have chosen greatness. Then from Sinai they were instructed about it, when You commanded us, Hashem, our G-d, to offer on it the Sabbath musaf offering properly. May it be Your will, Hashem, our G-d and G-d of our forefathers, that You bring us up in gladness to our Land and plant us within our boundaries...."

Reverse acrostics are quite rare in our liturgy. Another place we see a reverse acrostic is in the Tefillat Tal (Prayer for Dew) on Pesach. This alphabetic reversal evokes our longing for the return to a state of perfection, the World to Come, of which our Shabbat is only a shadow.

November 11, 2021

Attention: Reviewers of Jewish Historical Matter

Halakhically and Hashqafically Historical

- Brian Tice's profile

- 8 followers