Tim Prasil's Blog

January 21, 2026

The Genghis Khan of Crime: What If Sherlock Holmes Wasn’t as Law-Abiding as One Might Like?

“My name is Sherlock Holmes. … Possibly it is familiar to you. In any case, my business is that of every other good citizen—to uphold the law.”

— “Shoscombe Old Place”

A Dreadful “What If?”Look. Far be it from me to cast aspersions upon a fictional character with the respect and admiration of Sherlock Holmes. I imagine many of us like to envision him as close to how he describes himself in the epigraph above: a loyal and true defender of English law and order. Riiiiiiight?

Well, as I was reading Arthur Conan Doyle’s “canon” of Holmes adventures, I couldn’t help but notice the occasional flirting with the prospect of the great detective being an outlaw. I was also surprised by the multiple times he breaks the law to resolve a case.

Let’s start with those passages in which Holmes’s astounding abilities prompt those around him—as well as himself—to wonder what if the man with so much insight into crime had, indeed, led a life thereof:

“… I could not but think what a terrible criminal [Holmes] would have made had he turned his energy and sagacity against the law instead of exerting them in its defence.”

— Dr Watson, The Sign of the Four

“It is a mercy that you are on the side of the force, and not against it, Mr Holmes.”

— Inspector Gregson, “The Greek Interpreter”

“You know, Watson, I don’t mind confessing to you that I have always had an idea that I would have made a highly efficient criminal.”

— Sherlock Holmes, “Charles Augustus Milverton”

“It is fortunate for this community that I am not a criminal.”

— Sherlock Holmes, “The Bruce-Partington Plans”

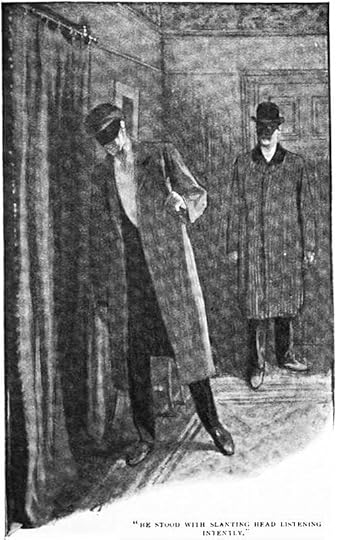

Holmes and Watson go a-burglin’ in “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton.”Crossing the Crooked Line

Holmes and Watson go a-burglin’ in “The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton.”Crossing the Crooked LineAnd then there are those times when, in fact, Holmes sidesteps (to put it gently) the law as a means to attain the greater good (to put it idealistically). He even exerts a corrupting influence on his faithful companion.

“You don’t mind breaking the law?”

“Not in the least.”

Sherlock Holmes and Dr Watson, “A Scandal in Bohemia”

“Watson, I mean to burgle Milverton’s house tonight.”

— Sherlock Holmes, “Charles Augustus Milverton” [and Watson again joins him]

“I have been three times in [Moriarty’s] rooms, twice waiting for him under different pretexts and leaving before he came. Once—well, I can hardly tell about the once to an official detective. It was on the last occasion that I took the liberty of running over his papers. …”

— Sherlock Holmes to Inspector MacDonald, The Valley of Fear

“My dear fellow, you shall keep watch in the street. I’ll do the criminal part. It’s not a time to stick at trifles.”

— Sherlock Holmes to Dr Watson, “The Bruce-Partington Plans”

“Sherlock Holmes was threatened with a prosecution for burglary, but when an object is good and a client is sufficiently illustrious, even the rigid British law becomes human and elastic.”

— Dr Watson, “The Illustrious Client”

“… I suppose I shall have to compound a felony as usual.”

— Sherlock Holmes, “The Three Gables”

“There being no fear of interruption I proceeded to burgle the house. Burglary has always been an alternative profession, had I cared to adopt it, and I have little doubt that I should have come to the front.”

— Sherlock Holmes to Inspector MacKinnon, “The Retired Colourman”

Not only does Holmes commit crimes, he admits as much—even to officials of Scotland Yard! (He seems especially comfortable doing so when said official has a Scottish surname. What’s that about?) Maybe this is partly explained by Holmes’s deep immersion into criminal behavior, which has tainted his worldview. In “The Copper Beeches,” while sharing a train ride with Watson, he admits he’s unable to enjoy watching the countryside go by:

[I]t is one of the curses of a mind with a turn like mine that I must look at everything with reference to my own special subject. You look at these scattered houses, and you are impressed by their beauty. I look at them, and the only thought which comes to me is a feeling of their isolation and of the impunity with which crimes may be committed there.Accordingly, Holmes sees a crime where there is no crime in both “The Yellow Face” and “The Lion’s Mane.”

And Watson seems a tad eager to fall in with the felonious fun. Without hesitation, the doctor joins Holmes in attempted burglary in “A Scandal in Bohemia.” In “Charles Augustus Milverton,” he raises only the flimsiest objections before telling Holmes that he “will take a cab straight to the police-station and give you away unless you let me share this adventure with you.” Even when Holmes is elsewhere, Watson partners with Sir Henry Baskerville in “aiding and abetting a felony,” to use the words of Sir Henry himself, by looking askance as arrangements are made to help a prison-escapee nicknamed the Notting Hill murderer flee the country. Perhaps lurking in the back of Watson’s mind is something Holmes says in “The Speckled Band”: “When a doctor goes wrong he is the first of criminals. He has nerve and he has knowledge [to commit murder by poison].” Did Watson hear this and begin to have very impure thoughts? Does this provide a glimpse into the disappearance of Mary, his wife?

Holmes intrudes upon Watson’s personal bubble in “The Abbey Grange.”An Era of Criminal Fog?

Holmes intrudes upon Watson’s personal bubble in “The Abbey Grange.”An Era of Criminal Fog?If asked for my favorite story now that I’ve finished the canon, I would go with “Charles Augustus Milverton.” It’s as if Doyle ached to write a story in which almost every character does something very naughty, if not blatantly illegal. The client has done something bad enough that the title character is blackmailing her. As a last resort, Holmes and Watson break into Milverton’s house to retrieve the incriminating letter. Remember, if the two are caught, the harm to their reputations might destroy their careers as detective and doctor! In the middle of this crime, our heroes stumble upon another very unexpected one, which they shrug off about an hour or two afterward. (Hey, Milverton was a wanker anyway.) In the end, Lestrade stands tall as the unblemished character, even though he fell short by, well, afoot of capturing those two masked dudes sneaking around Milverton’s house.

I’m left asking what thoughts regarding crime were swirling around when the Holmes tales were debuting. This is the time frame I used to select the fiction found in the Curated Crime Collection, all of which illustrates how difficult it sometimes can be to distinguish legal from illegal, moral from immortal, and good from bad. These blurred lines seem to have held a particular interest for many readers of the late-Victorian and Edwardian eras.

Then again, stories about crime have been around long before those decades, and they persist afterward. Yes, fictional criminals are far from confined to the late 1800s and early 1900s. Perhaps, something like Holmes, “I must look at everything with reference to my own special subject.”

— Tim

January 14, 2026

Mary Jones: Her Faith Was Not in That Candle

Fear not, Mary: for thou hast found favour with God.

— Luke 1:30

Finagling Fact and FolkloreIf the tale told “in the Welsh language by an old man” and transcribed in an 1847 issue of The Athenæum were, to some significant degree, historical fact, then Mary Jones (1694-1770) would certainly be one of the most remarkable figures inducted into the Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame. First, she’s among the earliest women paranormal investigators on record, having lived well before Catherine Crowe and Ada Goodrich-Freer, both of whom were born in the century after Jones died. Second, her response when confronting a dark, supernatural entity puts her alongside the most calm and courageous ghost hunters.

But Jones’s tale is far more likely a product of folklore. The bit in that article’s introduction about the man’s story being altered “to put an oral narration into readable form” suggests as much. Also, there are markedly different versions of the story.

Even as a folkloric figure, Mary Jones is noteworthy in what she reveals about 18th-century ghost hunting and gender roles. Also of interest is how the deeply religious Jones contrasts starkly to her predecessor Antoinette du Ligier de la Garde Deshoulières, whose ghost hunt illustrates the value of skepticism while similarly being the stuff of legend.

What Do We Know About Mary Jones?Most of what we can say about Mary Jones comes through what is recorded about her husband, the Reverend Edmund Jones (1702–93). One helpful source of information is a 2025 article titled “‘Original Memoirs of Apparitions & Spirits in Wales’ (c.1738): Publishing on the Supernatural in the Long Eighteenth Century,” written by Adam M. Coward and Martha McGill, and published in the academic journal Folklore. The authors tell us that the Jones’s marriage was “an exemplary one” and Mary shared her husband’s stalwart faith. Coward and McGill also cite sources revealing that Mary was subject to a targeted haunting, to attacks from the Devil, and to divination while asleep or awake. One might assume that our ghost hunter was also what was termed a “ghost seer,” meaning she had special sensitivities to supernatural presences.

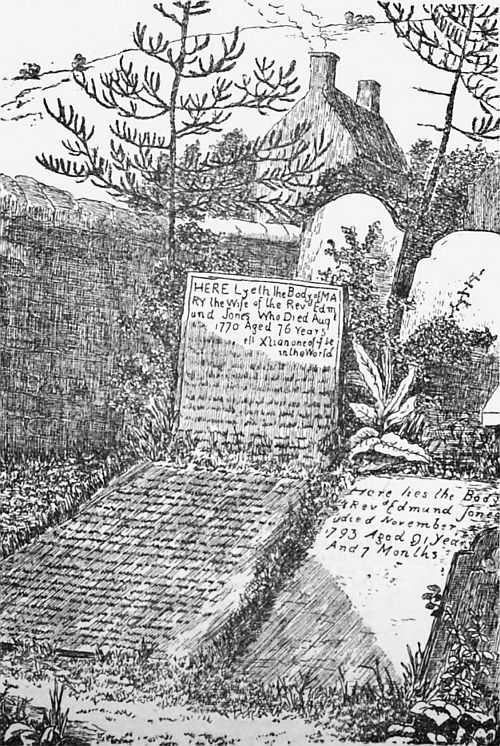

Edmund was an early folklorist with a particular interest in ghostly material, as shown in his A Relation of Apparitions of Spirits in the Principality of Wales (1780). (A smudgy but downloadable copy is at the Internet Archive while a clearer copy can be read online at the National Library of Wales.) Unfortunately, the tale of his wife’s encounter is not recorded there, and I suspect it rose after she had died.

This illustration of Mary and her husband’s gravesite comes from the 1882 Red Dragon article discussed below.The Jones-as-Ghost-Hunter Version

This illustration of Mary and her husband’s gravesite comes from the 1882 Red Dragon article discussed below.The Jones-as-Ghost-Hunter VersionThe Athenæum article presents Jones as a traditional ghost hunter. The tale opens with a setting that’s a bit more specific than once upon a time: “About the middle of the last century … in one of the mountainous districts of Monmouthshire [Wales], called Blaenau Gwent….” The transcription continues:

About this time, there was in that neighbourhood an old mansion-house, a certain part of which had long been unoccupied, being haunted,—especially one particular room, in which no one who knew the place could ever be induced to sleep; and such strangers as had, in a case of emergency, been put into it, could not remain there on account of the supernatural disturbances to which they were subject. At length, Mrs. Edmund Jones, having repeatedly heard of this, paid a visit to the house and requested to be allowed to pass the night in this apartment.In other words, Jones didn’t unknowingly stumble upon the haunted spot—no, she learned of it, went to it, and solicited permission to investigate it. Once there, she began her nocturnal surveillance of the room, remaining awake and alert while reading her Bible.

After a good long while, things started to happen. Jones then showed herself to be an unflappable paranormal investigator:

[S]he chanced to raise her head from the book, and to look up; when she beheld standing before her, on the opposite side of the table, a form of terrific aspect, with his eyes fixed fiercely on her. She fixed her eyes on him in return, and gazed upon him in the most composed and unconcerned manner. After they had remained for some time looking at each other, the demon spoke, and said, “Thy faith is in the candle.” “Thou lyest,” said she; and taking the candle out of the candlestick, she turned it down and extinguished it in the socket. Then, in the triumph of her faith, she folded her arms,—and continued in her seat, setting at defiance the powers of darkness.In proving that her faith—her strength, her courage—did not vanish along with the candlelight, Jones performed the work of exorcism: “From that time forth, the house never suffered from ghostly molestations.” The tale becomes a religious parable illustrating that a strong faith can protect us from the evil things that lurk in the darkness, and it uses a standard ghost hunter framework to make that point.

The Jones-as-Waylaid-Guest VersionJones herself actually existed, to be sure, but that we’re dealing with folklore instead of actual history is confirmed by there being two other versions of this “faith in your candle” tale. Though it’s a fairly simple variation, the next version removes Jones’s status as a ghost hunter. Instead, it draws from another familiar motif of ghost stories: a traveler’s only option is to spend the night in a room said to be haunted.

I found this version in J. Glyndwr Harris’s Edmund Jones: The Old Prophet (1987). Rather than solicit permission to probe a reported ghost, Jones finds herself stuck at a friend’s house due to stormy weather, her only choice of bedroom being one with a creepy reputation. We still see Jones’s courage in her response to the situation: “she was more ready to face the ghost than venture out into the storm.” Harris writes:

[Jones] told her friend that if she gave her a candle and a Bible she would have no fear of going into the spare room. So these were provided and she went to bed in the haunted room. In the early hours of the morning the ghost appeared in the guise of a decrepit old man. He made his ghostly way towards the bed and Mrs. Jones braced herself for the encounter. She remained calm and showed no fear. As he came near the ghost said, 'Woman, your faith is in that candle!' She was not put off her guard by his gibe and in an act of defiance she blew out the candle. The ghost disappeared and was never heard of again.Unfortunately, Harris’s sources are left undocumented. Whether this tale comes from, say, a newspaper article or maybe a book, well, we don’t know. I like to think Harris heard it still being told at the local pub.

Henry Gastineau’s “Aberystwith, or Blaenau Gwent,” from the 1830 edition of

Wales Illustrated, in a Series of Views, Comprising the Picturesque Scenery, Towns, Castles, Seats of the Nobility & Gentry, Antiquities, &c.

The Jones as Beer-Bringer Version

Henry Gastineau’s “Aberystwith, or Blaenau Gwent,” from the 1830 edition of

Wales Illustrated, in a Series of Views, Comprising the Picturesque Scenery, Towns, Castles, Seats of the Nobility & Gentry, Antiquities, &c.

The Jones as Beer-Bringer VersionThe final version I’ve found relocates the encounter to what’s probably its least spooky setting: the Jones’s own cellar. Granted, in the 1700s, this would be a place where it’s practical to bring a candle, but the fear factor goes pretty flat when we learn that Jones goes downstairs to retrieve some beer rather than, let’s say, investigate unearthly moans or some other kind of unnerving noise. This variation is found in an article titled “Monmouthshire Apparitions,” found in an 1882 issue of the magazine The Red Dragon:

It is told of Mrs. Jones that, going to the cellar one night for some beer, taking a candle to light her, she placed the jug beneath the tap and turned the key, but to her surprise there was no beer forthcoming; knowing the cask was nearly full, she looked up, and there, seated astride the cask, was the "foul fiend" himself in propria personæ. Nothing daunted at the sight, she coolly said in Welsh, "Oh, it's you who are there, is it?" "Yes," was the reply, "and your faith is in that candle." "You were always a liar," was her rejoinder, and she immediately blew the candle out. The devil, thus defied, gave in, and allowed the beer to run, and Mrs. Jones took it up in triumph for her husband's supper.It would be tough to call this a ghost story. It’s more of a the Devil himself story. Yet it’s clearly the same basic narrative as the two above. It’s as if the storyteller wanted to put an original spin on the thing, but felt a need to retain 1) some setting that would allow for a candle, 2) a supernatural challenge to Jones’s faith, and 3) her coolheaded triumph over that challenge.

Jones Granted Honorary MentionThere are four other Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame inductees whose status there depends on legend rather than factual history: Athenodorus, Antoinette du Ligier de la Garde Deshoulières, John Ruddle, and Richard Dodge. These are people who we have very good reason to believe actually lived, but whose respective acts of snooping around a haunted site seem impossible to verify. Mary Jones might have taken a place beside them. She might have, if the legend about her paranormal investigation were not undermined by those two variations that push her away from being a ghost hunter as I’ve come to define it. What’s key here is an intentional and well-planned investigation of a reported haunting, not an encounter with a spirit resulting from an accident and being at the wrong place at the wrong time.

Nonetheless, Jones’s story remains important to the legacy of ghost hunting. One of the primary goals of the Hall of Fame is to encourage paranormal investigators working today to discover and appreciate the rich heritage of which they are a part. Therefore, unless more evidence pops up, I am pleased to award Honorary Mention to the ever-resolute, ever-faithful Mary Jones.

January 7, 2026

Speculation on How and Where Dr. Watson Published His Holmes Chronicles, Part Three

Go to Part TwoThe Final Trio

I reached my end-of-2025 reading goal! I completed Arthur Conan Doyle’s four novels and five short-story collections featuring Sherlock Holmes, often referred to as “the canon.” However, I failed to solve the mystery of how or where Dr. John H. Watson went about publishing his chronicles of his remarkable friend and occasional flatmate. Not Doyle, mind you. Watson. According to those tales, the good doctor published his chronicles on a regular basis.

As mentioned in Part One, it’s reasonable to assume that readers in the Holmesverse came upon Watson’s first two narratives A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of the Four in pamphlet form. After all, in the latter, Watson refers to the former as “a small brochure” and “my pamphlet.” As novels go, these first two works are fairly short, making pamphlet somewhat more sensible than book. I’ve only scratched the surface of “true crime” pamphlets published in the Victorian era, and I’m finding they seem to focus on the trial of, say, a murderer rather than on a detective’s investigation of the case. Perhaps in this regard, Doyle was reinventing non-fiction pamphlets to better accommodate mystery fiction.

I’m forced to speculate, though, as to where those readers found the doctor’s many short-story-length chronicles, what he calls his “little narratives.” My guess is some widely read magazine, though I struggle to find any real-life parallel to a series of articles about a single detective’s methods and cases. Certainly, a series of 50-ish articles about any subject would have been very rare. That said, if Watson did published his shorter chronicles in a magazine or magazines, he might have then collected them in books, the pattern that Doyle and many other authors followed in the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Scrutinizing the EvidenceLet’s now examine what I found in the last of the canonical works. Spoiler: nothing very useful to my main concern. There are some secondary points of interest along the way, though.

The Return of Sherlock Holmes

“The Norwood Builder”

Watson, regarding Holmes: “His cold and proud nature was always averse … to anything in the shape of public applause, and he bound me in the most stringent terms to say no further of himself, his methods, or his successes—a prohibition which, as I have explained, has only now been removed.”

Holmes: “Perhaps I shall get the credit also at some distant day when I permit my zealous historian to lay out his foolscap once more—eh, Watson?”

“The Solitary Cyclist”

Watson, regarding Holmes’s many successes and few failures from 1894 to 1901: “As I have preserved very full notes of all these cases, and was myself personally engaged in many of them, it may be imagined that it is no easy task to know which I should select to lay before the public. … I will now lay before the reader the facts in connection with Miss Violet Smith. … It is true that the circumstances did not admit of any striking illustration of those powers for which my friend was famous, but there were some points about the case which made it stand out in those long records of crime from which I gather the material for these little narratives.

“The Six Napoleons”

Holmes: “If ever I permit you to chronicle any more of my little problems, Watson, I foresee that you will enliven your pages by an account of the singular adventure of the Napoleonic busts.”

“The Abbey Grange”

Holmes, taking a stance found in several earlier adventures: “I fancy that every one of [police detective Stanley Hopkins’] cases has found its way into your collection, and I must admit, Watson, that you have some power of selection which atones for much which I deplore in your narratives. Your fatal habit of looking at everything from the point of view of a story instead of as a scientific exercise has ruined what might have been an instructive and even classical series of demonstrations.” With a touch of spite, Watson suggests Holmes try writing one or two himself, and Holmes replies: “I will, my dear Watson, I will.” Indeed, he does so with “The Blanched Soldier” and “The Lion’s Mane,” both in The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes.

H.M. Brock’s depiction of Holmes in “The Adventure of the Red Circle“

H.M. Brock’s depiction of Holmes in “The Adventure of the Red Circle“His Last Bow

“Wisteria Lodge”

Holmes, to Watson: “If you cast your mind back to some of those narratives with which you have afflicted a long-suffering public, you will recognise how often the grotesque has deepened into the criminal.”

Holmes, to Scott Eccles: “You are like my friend, Dr Watson, who has a bad habit of telling his stories wrong end foremost.”

“The Devil’s Foot”

Watson, regarding Holmes: “To his sombre and cynical spirit all popular applause was always abhorrent, and nothing amused him more at the end of a successful case than to hand over the actual exposure to some orthodox official, and to listen with a mocking smile to the general chorus of misplaced congratulation. It was indeed this attitude upon the part of my friend and certainly not any lack of interesting material which has caused me of late years to lay very few of my records before the public.”

The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes

“The Three Garridebs”

John Garrideb, to Holmes: “Your pictures are not unlike you, sir, if I may say so.”

I believe this is the first mention of Holmes being “pictured” in Watson’s published accounts of the great detective.

After Holmes says his suit reveals Garrideb, who claims to be American, has been in England for some time, that man adds: “I’ve read of your tricks, Mr Holmes, but I never thought I would be the subject of them.” Here we see a client who knows about Holmes presumably from Watson’s chronicles, something that resurfaces in “The Veiled Lodger.”

“Thor Bridge”

Watson: “Somewhere in the vaults of the bank of Cox and Co., at Charing Cross, there is a travel-worn and battered tin dispatch-box with my name, John H. Watson, MC, Late Indian Army, painted upon the lid. It is crammed with papers, nearly all of which are records to cases to illustrate the curious problems which Mr Sherlock Holmes had at various times to examine. … In some I was myself concerned and can speak as an eye-witness, while in others I was either not present or played so small a part that they could only be told as by third person.” This last remark accounts for “The Mazarin Stone,” which is told in third-person and appears earlier in this collection.

Holmes: “I am getting into your involved habit, Watson, of telling a story backwards.”

“The Veiled Lodger”

Watson opens by explaining that at least one attempt has been made to destroy his records of certain sensitive cases. He then says other cases involved “the most terrible human tragedies.” The chronicle at hand involves one such case, and he adds, “In telling it, I have made a slight change of name and place, but otherwise the facts are as stated.” Here and there, Watson admits to smoothing out a client’s disjointed narration of the problem brought before Holmes, but for the most part he seems to be accurate and reliable. That is—if we’re to trust Watson himself.

H.K. Elcock’s depiction of Holmes and Watson in “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire“I Observe, but I Do Not See

H.K. Elcock’s depiction of Holmes and Watson in “The Adventure of the Sussex Vampire“I Observe, but I Do Not SeeAs mentioned, throughout my reading of the canon, I didn’t see anything solid to indicate the medium through which the Holmesverse public read Watson’s chronicles. While pamphlets are likely for the first two novels, what about the many, many stories following? Newspapers? Magazines? Books? A combination thereof? I only observed that the public did read them. And that Holmes routinely snubbed the manner in which Watson told those tales. And that—as Doyle’s output of Holmes adventures grew sporadic—the author “covered his tracks” by putting Holmes in control of which cases Watson was and wasn’t allowed to publish.

One more observation involves a complaint I’ve seen made by some mystery fans: Doyle doesn’t “play fair” with readers. We can’t “match wits” with Holmes because, with Watson as narrator, the detective is allowed to rush off and unravel clues on his own, keeping crucial information secret until The Big Reveal in the final scene. As Holmes states in “The Blanched Soldier” (1926):

The narratives of Watson have accustomed the reader, no doubt, to the fact that I do not waste words or disclose my thoughts while a case is actually under consideration.These tales come too early, however, to deem this a flaw. At the time the stories collected in The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes were debuting, from 1921 to 1927, some critics were introducing specific rules for mystery writers to follow, including those reader-based conventions involving playing fair and matching wits. (I touch on and link those rules here.) I wonder if Doyle had sensed that his style of mystery-storytelling was fading, and this lurks beneath Holmes’s jibes about Watson’s chronicles being told “wrong end foremost.” In other words, unlike Agatha Christie and her generation, Watson doesn’t narrate events chronologically from, let’s say, the arrival of the client to the exposure of the criminal. Watson doesn’t let readers play the game that’s afoot alongside the detective.

But that’s on Holmes himself, the tight-lipped bugger.

December 10, 2025

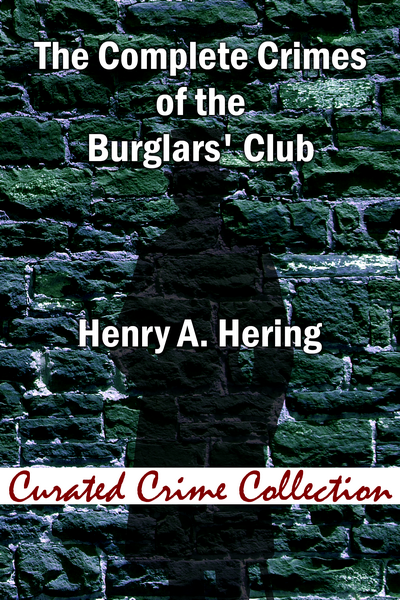

The Complete Crimes of the Burglars’ Club: All 18 of Hering’s Tales Together for the First Time (He Says With 99% Certainty)

After some determined research, I can say with a goodly amount of confidence that Brom Bones Books now offers something never before available: all eighteen of Henry A. Hering’s stories about the Burglars’ Club in a single volume.

The first twelve adventures were run in Cassell’s Magazine in 1904-1905. These were then reprinted as a book, one popular enough to be translated in several languages. But apparently Hering itched to divulge more about this organization comprised of good-hearted rogues. You see, the Club is made up of aristocrats who were so bored that they began to gather and dare one another to commit specific, quirky burglaries. Risking imprisonment along with the ruin of reputation, they consider it all a type of sport. It’s an intriguing premise, and in 1909-1910, Hering penned another six adventures for Cassell’s. As I say, the entire 18-installment series is collected — at along last — in The Complete Crimes of the Burglars’ Club.

I found this to be among the most flat-out fun selections in the Curated Crime Collection. Hering knew how to make his characters engaging and keep his plots crisp. While Grant Allen infuses The Curate of Churnside & An African Millionaire with a dark, sardonic sense of humor, Hering keeps his light. At times, I snorted out loud while proofreading at the coffee shop. Take, for instance, when one club member breaks into the office of Sir John Carder with the assignment to pilfer some of that man’s “exceptionally fine cigars.” The thief easily accomplishes his task late one night—despite coming upon his victim still at his desk. On hearing that Sir John is about to commit suicide due to financial disaster, however, our thief does what only the most gracious of criminals would do:

He plunged his hand into his pocket, and produced the box of cigars. 'Try one of these,' he said, offering them to Sir John. 'I can recommend 'em for big occasions.' This illustration appears on the cover of the 1906 collection of Hering’s Burglars’ Club tales. It was limited to the first dozen stories while the new Brom Bones Books edition features all eighteen.

This illustration appears on the cover of the 1906 collection of Hering’s Burglars’ Club tales. It was limited to the first dozen stories while the new Brom Bones Books edition features all eighteen.Things generally turn out well in these tales, although at least one sticky complication always seems to arise during every crime. And, as the epigraph above suggests, the Club’s rules hold that all stolen items be returned within a day or two. Hering’s artistic goal is simply to entertain, not to provide an authentic picture of the causes and consequences of crime, something one finds in, say, Josiah Flynt’s The Rise of Ruderick Clowd. (Flynt’s realistic novel, by the way, is paired with Mariam Michelson’s In the Bishop’s Carriage in another volume of the Curated Crime Collection.) That said, there might be some subtle social satire here, whether it’s ribbing the upper crust outright or revealing the class disparity in how crime is understood and punished.

You’ll find more about The Complete Crimes of the Burglars’ Club on this page. Nose around a bit, and you’ll find those volumes spotlighting Allen, Flynt, and Michelson.

— Tim

.

November 26, 2025

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Very Tall Apparition in Galway

Clues to an Eight-to-Nine Foot Ghost

Clues to an Eight-to-Nine Foot GhostIn late 1908, multiple witnesses were reported to have encountered a towering spectral figure moving along the railway tracks in Galway, Ireland. One article in a Welsh newspaper puts the ghost’s height at “about nine feet in height.” A later report reprinted in papers from the U.S. state of Mississippi to the Taranaki region of New Zealand puts it at eight-foot. Given the excitement that comes with witnessing a ghost, we can settle on this one being, well, very tall.

An article appropriately titled “A Very Tall Ghost” introduces a problem in the case. It says the first two witnesses were “at a place called Glenville” when they first spotted the ghost. While I can find this place called Glenville on a map, I’ve found no evidence that tracks would have ever existed there. Other Welsh reports call the location “Glanville” and “Granville” — at times, in the very same article — but I can’t find those names near Galway. Was Glenville/Glanville/Granville a pub perhaps? Some other gathering spot? Unless someone says tells me otherwise, I’m concluding that this clue became waterlogged as it crossed St. George’s Channel from Ireland to Wales.

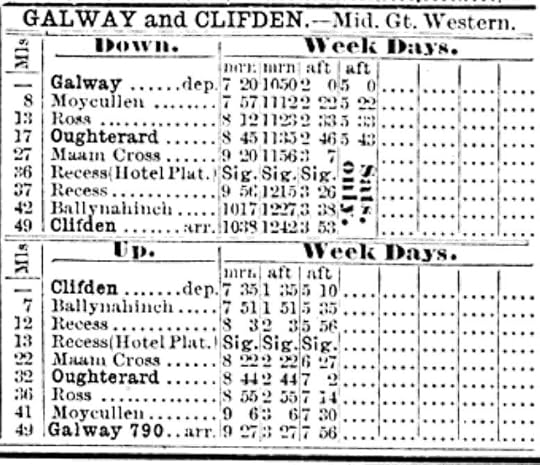

Luckily, another Welsh report adds that those two witnesses were “taking a short cut on the railway line to Galway from Newcastle,” and this is repeated in those papers in the United States and New Zealand. Here’s a much more helpful clue! It suggests our initial witnesses were very likely on the Galway and Clifden Railway, a branch of the Midland Great Western, whose tracks went northwest from Galway while hugging the west bank of the Corrib River. They look as if they would’ve gone fairly close to Newcastle. At least, closer to Newcastle than to Glenville.

From the April 1906 issue of Bradshaw’s Monthly Railway and Steam Navigation Guide. Scroll down to find a route map here, and you’ll see that the trains went fairly close to Newcastle but not near to Glenville.

From the April 1906 issue of Bradshaw’s Monthly Railway and Steam Navigation Guide. Scroll down to find a route map here, and you’ll see that the trains went fairly close to Newcastle but not near to Glenville.Sadly, this railway closed in the 1930s, and the site of a restoration project at Maam Cross suggests the tracks were removed long ago. Finding where they once were might be very tricky.

Fear Not! There’s Much Better ClueIt’s those international papers that provide “the smoking gun” to anyone wishing to investigate any paranormal energy lingering today. First, this report describes a growing number of witnesses, presumably made curious by the earlier reports. We also are told that new sightings of the apparition place it at “the railway viaduct across the bank of the stream….” Indeed, an additional witness “declares that he saw it jump from the top of the viaduct into the Corrib, where it disappeared.”

The Galway & Clifden viaduct

The Galway & Clifden viaductDoes that viaduct still exist? Well, while the tracks across it were removed with those on the land before and beyond, the stone pilings upon which they once rested remain, and they can be visited. Photos and a map are provided here. The best landmark is the the Salmon Weir a bit to the south. The Angling Ireland site says the cost of fishing in this stretch of river depends on where you cast your line. I’m not sure if there are any fees for ghost hunting. All I can say is: be courteous, and be smart.

On the one hand, if you do investigate the site of the once-haunted viaduct, you’ll have to do it from a bit of a distance. On the other, it’s a very tall ghost, so it might be easily seen! If you make the attempt, regardless of the results, I’d love to read about your experience in a comment below.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore.

October 29, 2025

Brom Bones on the Screen: The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1999)

— Washington Irving, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow“

About as True to Irving as It GetsI have a special affection for the 1999 adaptation of Irving’s tale, going by the same title and directed by Pierre Gang. It’s a cozy, leisurely paced, family-friendly version that comes about as close to the original as I’ve seen. This version is much less Hollywood and much more — let’s go with Canadian, which is where it was cast and filmed.

Despite its faithfulness to Irving, there are some added touches. For instance, there’s a narrative frame involving a stormy night and the arrival at a Tarry Town inn of none other than Geoffrey Crayon. This is the pseudonym/persona Irving uses to weave together his collection The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., which includes “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” In the adaptation, it’s at this rustic inn where a gaggle of old-timers tells Crayon the yarn about a quirky fellow named Ichabod Crane, who passed through the village several years back.

On a dark and stormy night — and beside a cozy fire — Geoffrey Crayon (Paul Hopkins) records the local lore of Sleepy Hollow in his sketch book.

On a dark and stormy night — and beside a cozy fire — Geoffrey Crayon (Paul Hopkins) records the local lore of Sleepy Hollow in his sketch book.Another twist is Katrina having her own wants and the courage to stand up for them instead simply catering to the wants of her suitors. In Irving’s story, she’s treated as little more than the village’s most attractive candidate for marriage: “a blooming lass of fresh eighteen; plump as a partridge; ripe and melting and rosy-cheeked as one of her father’s peaches.” But in this version, she resolutely rejects Crane’s proposal of marriage, knowing full well that he’s primarily interested in the big farm that’ll come with her and the little babies who’ll come from her. In addition, her desire to visit her ancestral homeland of Amsterdam clashes with Brom Bones’ plan to go west and establish his own farm, making her uncertain about their future together.

Speaking of Brom, one twist that is… well… interesting arrives at the very end. In the original story, Irving concludes with the suggestion that the Headless Horseman who chased Ichabod out of town might very well have been Brom in disguise. Rather than spoil how this version spins that, I’ll just say that those old-timers entertaining Geoffrey Crayon might’ve imbibed too much ale. It’s not a terrible change, mind you. It’s just… interesting.

Speaking of BromRegarding Brom Bones, Irving writes:

This rantipole hero had for some time singled out the blooming Katrina for the object of his uncouth gallantries, and though his amorous toyings were something like the gentle caresses and endearments of a bear, yet it was whispered that she did not altogether discourage his hopes.One of the great things about Irving’s Brom is his mix of uncouthness and gallantry. It makes him a round character with a pinch more complexity than one who’s flat or definable with a single word.

On a not-quite-so dark and stormy night — but beside another cozy fire — Brom Bones (Paul Lemelin) tells of his own encounter with the Headless Horseman

On a not-quite-so dark and stormy night — but beside another cozy fire — Brom Bones (Paul Lemelin) tells of his own encounter with the Headless HorsemanThere’s something else going on this adaptation. Brom, played by Paul Lemelin, easily wins the audience’s sympathy over Brent Carver’s wonderfully sputtering, fastidious, sycophantic Ichabod. There’s not much rantipole-ishness to this Brom, and whatever bear-ishness there is winds up being softened with teddy-ishness. This Brom is defined more by lingering boyhood competing with that desire to make his own way in the world with Katrina by his side. One might even see this version as Brom’s coming-of-age story, if one were inclined to put as him at the narrative core.

And true to form, Brom wins Katrina’s hand in marriage (after they resolve their west-or-east travel plans). We rejoin Crayon and the old-timers at the Tarry Town inn, and our evening of fireside-stories-within-fireside-stories ends with a feeling of having been among those listening to a quaintly amusing and curiously soothing tale. I very much recommend this adaptation, and it’s pretty easy to find on streaming formats and elsewhere.

— Tim

Click Here to Read aboutOther Screen Adaptations

of Irving’s Classic Work

October 22, 2025

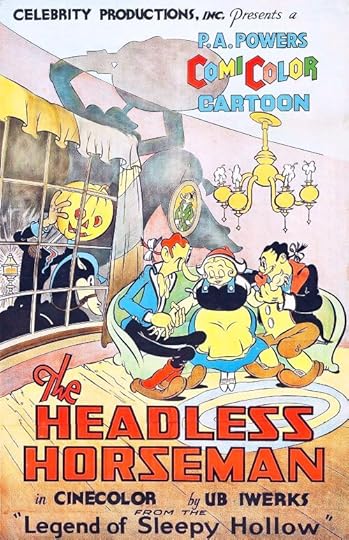

Brom Bones on the Screen: “The Headless Horseman” (1934) and “Ichabod Crane or The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1949)

— Washington Irving, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow“

A 1934 Animated VersionIn the quotation above, we see that Washington Irving closes his famous tale with a fairly strong suggestion that Brom Bones had a hand in frightening Ichabod Crane out of Tarry Town, clearing a path to marry Katrina Van Tassel. In an earlier post, I discuss a 1922 film in which Will Rogers plays Ichabod, and here Irving’s suggestion becomes solid fact when Brom removes the Headless Horseman costume and guffaws as his rival hightails it into the distance. A 1934 cartoon version of the story does the same, erasing any ambiguity found in Irving’s finale. (But the cartoon also adds a brand new surprise at the end, too!)

This cartoon is titled “The Headless Horseman,” and given the year, it might surprise you that it’s in color. It’s also reasonably faithful to the source material — well, about as faithful as a retelling can be with virtually no dialogue and a running time under nine minutes. Its depiction of Brom is pretty close to Irving’s, too, in that he’s a brawny bumpkin who uses what wits he has to ensure that Ichabod’s own gullibility is largely responsible for that highbrow man’s loss of Katrina’s hand.

On a side note, Katrina reveals she secretly prefers Brom when she imagines him to be the equivalent of, uhm, I want to say that’s Clark Gable, given the ears…. Okay, maybe this screen version isn’t all that faithful to Irving.

You can watch “The Headless Horseman” on YouTube, but be warned that its depiction of Tarry Town’s Black citizens leans hard on the denigrating caricature of the time.

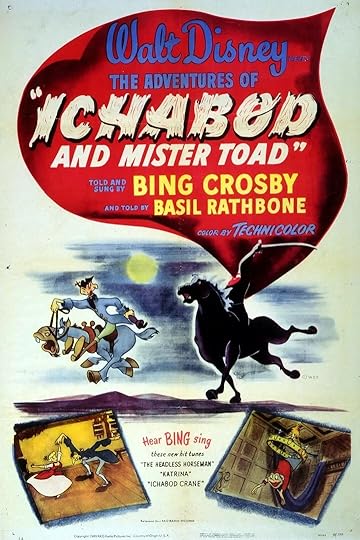

A 1949 Animated VersionDisney’s 1949 animated retelling of the tale is deservedly beloved by many. The main title is “Ichabod Crane,” presumably to match “Mr. Toad,” the retitling of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, which makes up the first half of the whole movie. If you happen to think of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” as specifically a Halloween story, it might be traced back to this film’s repeated mentions of that day. Irving, you see, only specifies the climax of the story as happening during “the sumptuous time of autumn,” and to be sure, the Celtic-rooted holiday would have been far from familiar to the original story’s Dutch-American characters living in the late 1700s.

As with the 1934 cartoon, this portrait of Brom is at least in the ballpark of how Irving drew him: muscular, chummy, equestrian, and more shrewd and sly than brutal and boorish.

This movie debuted almost a decade after Disney studios dazzled audiences with the animation artistry of Fantasia, so it follows that it offers one of the greatest chase scenes of any film version. Interestingly, after that chase, the film never says or even hints that Brom might’ve been masquerading as the legendary phantom, allowing the audience to presume that the Headless Horseman was — well — the Headless Horseman. In an ending that feels a bit rushed compared to other versions, the audience learns that Ichabod disappeared, and despite a rumor that he settled elsewhere, the superstitious folk of Tarry Town prefer to think he was spirited away by their local decapitated demon.

Despite its spin on the finale, this version still has Brom wed Katrina, something that doesn’t happen in some of the films to follow. More to come.

— Tim

Click Here to Read aboutOther Screen Adaptations

of Irving’s Classic Work

October 15, 2025

Brom Bones on the Screen: The Headless Horseman (1922)

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

SubscribeOctober 8, 2025

The Scarlet Pencil: Dialing Down Dialect

The seventh volume of the Curated Crime Collection will feature all eighteen of Henry A. Hering’s wonderful stories about the Burglars’ Club. After running in Cassell’s Magazine, the first dozen tales were collected in a 1906 book titled The Burglars’ Club: A Romance in Twelve Chronicles. About five years later, Hering wrote six additional tales, and so far as I know, the full set has never been released as a book. That is—until my edition debuts, which I hope will be in a month or two.

I try to use a light hand when editing the Curated Crime books, but I’ve had to raise my hand to signal HALT! from time to time. While Hering uses a very modern language style—closer to the terseness of Hemingway than the “wordiness” of Dickens—his use of dialect can feel pretty clumsy by today’s standards. He does okay when it comes to, say, Cockney characters, but his German characters’ thick accents become downright annoying. This is partly because conventions for dialect have changed between the early 20th- and early 21st-centuries. Indeed, Hering is simply doing what many other writers of his era did. But it’s also because some of his ways to designate a German accent don’t make sense.

An illustration from Hering’s incomplete collection of Burglars’ Club adventures.Editing for Believability and Consistency

An illustration from Hering’s incomplete collection of Burglars’ Club adventures.Editing for Believability and ConsistencyFor instance, in “The Holbein Miniature,” Hering has Mr. Adolf Meyer ask Mr. Lucas what he thinks of when he looks out over the sea. The later says he thinks of boating and bathing, and Meyer then reveals himself to be a man of deeper thoughts:

Dat is where you islanders have the advantage over us treamers. But somehow the treams have a habit of outlasting de practice.... I tink of all dat is above it, and below it. On de top, ships carrying men and women and children to continents; below de waves, dead men and women and children, dose who have died by de way, floating by de cables which are carrying words dat make and unmake nations and men. Life and death are dere togedder.Th can be a difficult sound for those whose primary language doesn’t have that sound. Changing “there together,” to “dere togedder” makes for a believable accent (even though a “thin” and a “through” slip by elsewhere in Meyer’s dialog). But if someone can pronounce a d, why would that person turn “dreamers” into “treamers”? They probably wouldn’t. It’s simply a way to reinforce the character’s accent.

This accent-for-accent’s-sake approach can also seen when Meyers changes “photographs” to “photokraphs,” even though he is capable of putting the hard g into “Mein Gott!” And “prescriptions” becomes “brescriptions” even though Meyer can pronounce the b in “bekinning.” And “telescope” becomes “delescope” even though he seems able to pronounce all three t sounds in “shut my window tight.” Such dialect is inconsistent, which makes it unbelievable—which makes it a bit annoying. Look, Hering, I’m loving the story—and I get that the character is German—but if you’re koing to bersist in dransbosing letters, at least, stick to your kuns!

As I say, Hering is simply following dialect conventions of the early 1900s. I’ve seen the same in plenty of other pieces from that era’s fiction. It’s not a weakness. But it is an annoyance for fiction readers today, when the convention has become to gently remind readers of a particular accent. We’ll hear the accent in our imaginations, after all.

What’s more is Meyer, we’re told, has earned both an M.A. degree from London University and a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order from the British monarch. His English should be pretty good! Given these problems, I stepped in and converted everything this character says to standard English, all except for changing the th sounds to d sounds.

A Character Even More GermanA later tale, titled “The Truth Extorter,” introduces another German character. Dr. Bamburger doesn’t have nearly the same familiarity with English as Meyer, but his dialect is virtually the same. It also exhibits many of the same problems of believability and consistency:

Dere is a patch of prown, but not as big or as dark as I should haf expected...Bamburger can’t say “brown,” but he can say “but” and “big”? Weird.

I vill not hand you to dem. Sit down; dat is all I want.Shouldn’t a character who turns “will” into “vill” also turn “want” into “vant”? And then Bamburger says “mitout” instead of “without.” Granted, the film term MOS or “mit out sound” allegedly sprang from a German director mispronouncing “without sound,” but turning w into v and afterwards into m — and elsewhere not doing anything at all with it—asks readers to juggle a lot.

In Bamburger’s case, I again made th sounds into d sounds and turned all w sounds into v sounds. This, I hope, is enough to suggest he has a thicker accent than Meyer along with granting readers’ imaginations the freedom to do the rest.

Despite my qualms about the dialect, I think Hering’s Burglars’ Club series has some really great storytelling in it! It’s engaging, funny, and seems to be saying something about the bored aristocrats who spice up their lives by burgling offbeat items from their almost-always aristocratic neighbors. I hope my dialing down the dialect will make a very enjoyable reading experience a little bit more enjoyable.

— Tim

(Posts identified as “The Scarlet Pencil” chronicle my meandering through the misty and mysterious quagmire of editing books.)

October 1, 2025

Byard’s Leap: The Winding History of a Single Bound

The legend of Byard’s Leap is as much about a heroic horse as it is about a horrible hag. I’ll try to summarize the narrative, even though — as we’ll explore — there are several variations on it.

Northwest of Sleaford, in Lincolnshire, England, is a spot known as Byards Leap. The curious name is a reference to a tremendous jump made by a horse once upon a time. You see, the local people were plagued by a nasty witch, one along the lines of, say, Black Annis, in that she lived in a cave, had long talon-like fingernails, and, some say, feasted on children.Luckily, a hero rose to vanquish the witch. At a nearby pond where horses gathered, he tossed a rock into the water to observe and select the steed with the quickest response time and/or with divine approval for the task at hand. The one he chose was named Byard (sometimes spelled Bayard or Biard).

The hero mounted Byard and rode off to confront the witch. There, a struggle began, and the witch dug her creepy fingernails into Byard. The poor horse lunged into the air and landed far, far away! In the process, the witch perished.

But the hoofprints left from Byard's Leap remain to this day. In fact, there are photos in this well-researched article written by Rory Waterman for the Lincolnshire Folk Tales Project.

As one expects, this legend evolved over time, different renditions swapping out specifics. I figured it might be interesting and hopefully useful to researchers if I were to dig up what I could on the printed history of the oral tradition. Below, then, is an informal annotated bibliography, chronologically ordered, of the Byard’s Leap narrative.

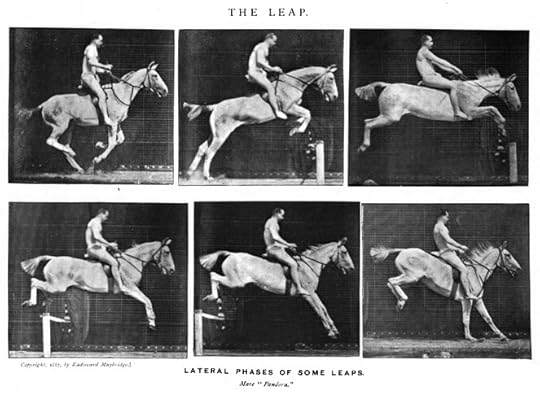

Tragically, no photograph seems to exist of Byard’s legendary leap (which suggests poor planning on the hero’s part). This substitute comes from Eadweard Muybridge’s Animals in Motion: An Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Progressive Movements (1899)Permutations Across Centuries

Tragically, no photograph seems to exist of Byard’s legendary leap (which suggests poor planning on the hero’s part). This substitute comes from Eadweard Muybridge’s Animals in Motion: An Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Progressive Movements (1899)Permutations Across Centuries1704: Anonymous, . This source is a travel journal purportedly written in 1704 and finally published in 1818. The unnamed author makes a quick reference to Byard’s hoofprints, which are “16 yards” apart. Knowing his readers might scoff at such a distance, the traveler teases: “But then, you must know, the horse was frightened by a witch, or perhaps he never leap so farr; and the people hereabouts keep the marke of the leap, on purpose to be seen.”

1776: William Stukeley’s Itinerarium Curiosum; Or, An Account of the Antiquities and Remarkable Curiosities in Nature and Art, Observed in Travels through Great Britain. Another travelogue, this one from the latter half of the eighteenth century, also refers to the spot. Stukeley writes: “[H]ere is a cross of stone, and by it four little holes made in the ground: they tell silly stories of a witch and horse making a prodigious leap, and that his feet rested in these holes, which I think rather the boundaries for four parishes….” Apparently, Stukeley didn’t know how to have fun.

1846: G. Oliver’s The Existing Remains of the Ancient Britons, Within a Small District Lying Between Lincoln and Sleaford. Oliver provides a much more detailed rendition of the legend. Here, we learn that “our witch was very cunning in the capture of children, which she carried to her cave and devoured.” Our hero is described as “A knight of tried courage, during the age of chivalry….” Our horse now jumps “at least 60 yards,” and does so three times.

1863: Edward Trollope’s “Lincoln Heath, and Its Historical Associations.” Though Trollope doesn’t mention any snacking on children, the witch here “was seen cowering over a fire emitting a blue unearthly light, and sometimes flitting bat-like through the shades of night, intent on mischief towards man and beast.” No precise yardage is mentioned, but “the witch’s claws deepen in the shoulders of the knight and the flanks of the horse; when happily the former calls to mind a cross road near at hand, and if he can but reach this he is safe. He pulls the left rein, therefore, and away bounds Bayard in that direction, until with one prodigious effort he clears the point of junction, and the witch falls dead before the leap is accomplished.” In other words, Byard’s mighty bound over a mystically powerful crossroad defeats the witchy foe.

1878: S.M. Mayhew’s “Welbourne, Lincolnshire, and Its Neighbourhood.” Now, the hero is something of a witch-hunter, one “whose mission appears to have been in delivering earth from sorcerers.” In his skirmish with the witch, Byard jumps three times, “each of about 170 feet.”

1891: J. Conway Walter’s “The Legend of Byard’s Leap.” Byard’s record is now set at “sixty feet,” and — replacing the knight — a “shepherd is selected for the enterprise” of defeating the witch. This revision makes the hero a much more humble one — instead of Bruce Wayne, he’s Peter Parker (before the big bite!) — and this builds tension, given his inexperience with slaying stuff. Also, unless I missed something, this is my first source that says Byard is blind, and Walter explains that this is “a providential circumstance, since it is likely that any horse which could see would shrink from contact with the witch.” Instead of a deadly crossroad, the witch falls off Byard and down into a pond, where she drowns. Witches and water have an uneasy history.

1895: Sidney Oldall Addy’s “25–Byard’s Leap.” As with Walter, the hero shifts from a gallant knight to an ordinary bloke, specifically, one of the local farmers. Byard is once again blind. That horse’s three leaps now measure “seven yards.” A simple knife wound costs the witch her powers, though perhaps not her life. I like to think she found a new career as a manicurist.

1904: M.P.’s “63. Bayard’s Leap and the Late Canon Atkinson’s View of the Legend.” M.P.’s goal is to establish the earliest known version of the ever-evolving tale. The witch is back to eating people and residing in a cave, and the hero is back to being a wandering knight. There’s a quick note that the special horse was “sometimes called the blind Bayard,” and another one about versions disagreeing about whether the horse jumped three times or only once. Here, the witch dies from the knight’s sword.

Reboots Are Nothing NewI’m sure there are more transcriptions of the legend out there, but this is enough to suggest how it morphed over time. What makes the witch so dreaded? Who slays her, and how does she die? Is Byard blind or not? These are questions different narrators answer differently. Nonetheless, the story retains its essentials: a bad witch, a brave hero, a chosen horse, a deep stab, a mighty leap, and a dead witch. Oh, and holes in the ground to “prove it.”

In fact, the legend continues to take on new forms. None of the sources above provides a name for the witch, but these days, you’ll find her called Old Meg or Black Meg. The former is found in this version along with a full backstory for her, one in which the conquering knight is her former sweetheart — and really quite a jerk!

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.