Tim Prasil's Blog

November 26, 2025

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Very Tall Apparition in Galway

Clues to an Eight-to-Nine Foot Ghost

Clues to an Eight-to-Nine Foot GhostIn late 1908, multiple witnesses were reported to have encountered a towering spectral figure moving along the railway tracks in Galway, Ireland. One article in a Welsh newspaper puts the ghost’s height at “about nine feet in height.” A later report reprinted in papers from the U.S. state of Mississippi to the Taranaki region of New Zealand puts it at eight-foot. Given the excitement that comes with witnessing a ghost, we can settle on this one being, well, very tall.

An article appropriately titled “A Very Tall Ghost” introduces a problem in the case. It says the first two witnesses were “at a place called Glenville” when they first spotted the ghost. While I can find this place called Glenville on a map, I’ve found no evidence that tracks would have ever existed there. Other Welsh reports call the location “Glanville” and “Granville” — at times, in the very same article — but I can’t find those names near Galway. Was Glenville/Glanville/Granville a pub perhaps? Some other gathering spot? Unless someone says tells me otherwise, I’m concluding that this clue became waterlogged as it crossed St. George’s Channel from Ireland to Wales.

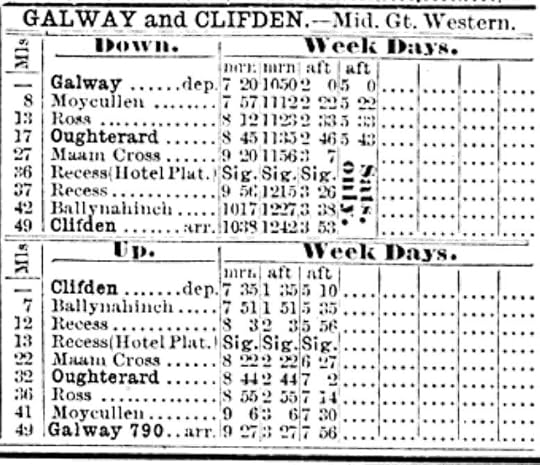

Luckily, another Welsh report adds that those two witnesses were “taking a short cut on the railway line to Galway from Newcastle,” and this is repeated in those papers in the United States and New Zealand. Here’s a much more helpful clue! It suggests our initial witnesses were very likely on the Galway and Clifden Railway, a branch of the Midland Great Western, whose tracks went northwest from Galway while hugging the west bank of the Corrib River. They look as if they would’ve gone fairly close to Newcastle. At least, closer to Newcastle than to Glenville.

From the April 1906 issue of Bradshaw’s Monthly Railway and Steam Navigation Guide. Scroll down to find a route map here, and you’ll see that the trains went fairly close to Newcastle but not near to Glenville.

From the April 1906 issue of Bradshaw’s Monthly Railway and Steam Navigation Guide. Scroll down to find a route map here, and you’ll see that the trains went fairly close to Newcastle but not near to Glenville.Sadly, this railway closed in the 1930s, and the site of a restoration project at Maam Cross suggests the tracks were removed long ago. Finding where they once were might be very tricky.

Fear Not! There’s Much Better ClueIt’s those international papers that provide “the smoking gun” to anyone wishing to investigate any paranormal energy lingering today. First, this report describes a growing number of witnesses, presumably made curious by the earlier reports. We also are told that new sightings of the apparition place it at “the railway viaduct across the bank of the stream….” Indeed, an additional witness “declares that he saw it jump from the top of the viaduct into the Corrib, where it disappeared.”

The Galway & Clifden viaduct

The Galway & Clifden viaductDoes that viaduct still exist? Well, while the tracks across it were removed with those on the land before and beyond, the stone pilings upon which they once rested remain, and they can be visited. Photos and a map are provided here. The best landmark is the the Salmon Weir a bit to the south. The Angling Ireland site says the cost of fishing in this stretch of river depends on where you cast your line. I’m not sure if there are any fees for ghost hunting. All I can say is: be courteous, and be smart.

On the one hand, if you do investigate the site of the once-haunted viaduct, you’ll have to do it from a bit of a distance. On the other, it’s a very tall ghost, so it might be easily seen! If you make the attempt, regardless of the results, I’d love to read about your experience in a comment below.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore.

October 29, 2025

Brom Bones on the Screen: The Legend of Sleepy Hollow (1999)

— Washington Irving, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow“

About as True to Irving as It GetsI have a special affection for the 1999 adaptation of Irving’s tale, going by the same title and directed by Pierre Gang. It’s a cozy, leisurely paced, family-friendly version that comes about as close to the original as I’ve seen. This version is much less Hollywood and much more — let’s go with Canadian, which is where it was cast and filmed.

Despite its faithfulness to Irving, there are some added touches. For instance, there’s a narrative frame involving a stormy night and the arrival at a Tarry Town inn of none other than Geoffrey Crayon. This is the pseudonym/persona Irving uses to weave together his collection The Sketch Book of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent., which includes “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow.” In the adaptation, it’s at this rustic inn where a gaggle of old-timers tells Crayon the yarn about a quirky fellow named Ichabod Crane, who passed through the village several years back.

On a dark and stormy night — and beside a cozy fire — Geoffrey Crayon (Paul Hopkins) records the local lore of Sleepy Hollow in his sketch book.

On a dark and stormy night — and beside a cozy fire — Geoffrey Crayon (Paul Hopkins) records the local lore of Sleepy Hollow in his sketch book.Another twist is Katrina having her own wants and the courage to stand up for them instead simply catering to the wants of her suitors. In Irving’s story, she’s treated as little more than the village’s most attractive candidate for marriage: “a blooming lass of fresh eighteen; plump as a partridge; ripe and melting and rosy-cheeked as one of her father’s peaches.” But in this version, she resolutely rejects Crane’s proposal of marriage, knowing full well that he’s primarily interested in the big farm that’ll come with her and the little babies who’ll come from her. In addition, her desire to visit her ancestral homeland of Amsterdam clashes with Brom Bones’ plan to go west and establish his own farm, making her uncertain about their future together.

Speaking of Brom, one twist that is… well… interesting arrives at the very end. In the original story, Irving concludes with the suggestion that the Headless Horseman who chased Ichabod out of town might very well have been Brom in disguise. Rather than spoil how this version spins that, I’ll just say that those old-timers entertaining Geoffrey Crayon might’ve imbibed too much ale. It’s not a terrible change, mind you. It’s just… interesting.

Speaking of BromRegarding Brom Bones, Irving writes:

This rantipole hero had for some time singled out the blooming Katrina for the object of his uncouth gallantries, and though his amorous toyings were something like the gentle caresses and endearments of a bear, yet it was whispered that she did not altogether discourage his hopes.One of the great things about Irving’s Brom is his mix of uncouthness and gallantry. It makes him a round character with a pinch more complexity than one who’s flat or definable with a single word.

On a not-quite-so dark and stormy night — but beside another cozy fire — Brom Bones (Paul Lemelin) tells of his own encounter with the Headless Horseman

On a not-quite-so dark and stormy night — but beside another cozy fire — Brom Bones (Paul Lemelin) tells of his own encounter with the Headless HorsemanThere’s something else going on this adaptation. Brom, played by Paul Lemelin, easily wins the audience’s sympathy over Brent Carver’s wonderfully sputtering, fastidious, sycophantic Ichabod. There’s not much rantipole-ishness to this Brom, and whatever bear-ishness there is winds up being softened with teddy-ishness. This Brom is defined more by lingering boyhood competing with that desire to make his own way in the world with Katrina by his side. One might even see this version as Brom’s coming-of-age story, if one were inclined to put as him at the narrative core.

And true to form, Brom wins Katrina’s hand in marriage (after they resolve their west-or-east travel plans). We rejoin Crayon and the old-timers at the Tarry Town inn, and our evening of fireside-stories-within-fireside-stories ends with a feeling of having been among those listening to a quaintly amusing and curiously soothing tale. I very much recommend this adaptation, and it’s pretty easy to find on streaming formats and elsewhere.

— Tim

Click Here to Read aboutOther Screen Adaptations

of Irving’s Classic Work

October 22, 2025

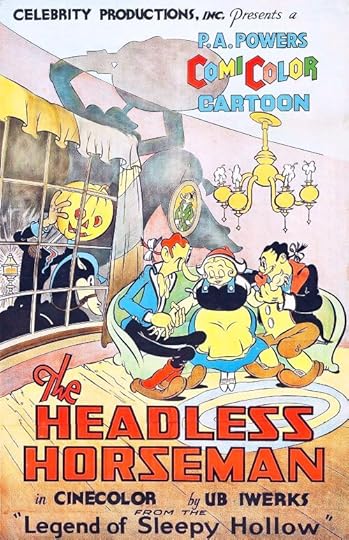

Brom Bones on the Screen: “The Headless Horseman” (1934) and “Ichabod Crane or The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” (1949)

— Washington Irving, “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow“

A 1934 Animated VersionIn the quotation above, we see that Washington Irving closes his famous tale with a fairly strong suggestion that Brom Bones had a hand in frightening Ichabod Crane out of Tarry Town, clearing a path to marry Katrina Van Tassel. In an earlier post, I discuss a 1922 film in which Will Rogers plays Ichabod, and here Irving’s suggestion becomes solid fact when Brom removes the Headless Horseman costume and guffaws as his rival hightails it into the distance. A 1934 cartoon version of the story does the same, erasing any ambiguity found in Irving’s finale. (But the cartoon also adds a brand new surprise at the end, too!)

This cartoon is titled “The Headless Horseman,” and given the year, it might surprise you that it’s in color. It’s also reasonably faithful to the source material — well, about as faithful as a retelling can be with virtually no dialogue and a running time under nine minutes. Its depiction of Brom is pretty close to Irving’s, too, in that he’s a brawny bumpkin who uses what wits he has to ensure that Ichabod’s own gullibility is largely responsible for that highbrow man’s loss of Katrina’s hand.

On a side note, Katrina reveals she secretly prefers Brom when she imagines him to be the equivalent of, uhm, I want to say that’s Clark Gable, given the ears…. Okay, maybe this screen version isn’t all that faithful to Irving.

You can watch “The Headless Horseman” on YouTube, but be warned that its depiction of Tarry Town’s Black citizens leans hard on the denigrating caricature of the time.

A 1949 Animated VersionDisney’s 1949 animated retelling of the tale is deservedly beloved by many. The main title is “Ichabod Crane,” presumably to match “Mr. Toad,” the retitling of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, which makes up the first half of the whole movie. If you happen to think of “The Legend of Sleepy Hollow” as specifically a Halloween story, it might be traced back to this film’s repeated mentions of that day. Irving, you see, only specifies the climax of the story as happening during “the sumptuous time of autumn,” and to be sure, the Celtic-rooted holiday would have been far from familiar to the original story’s Dutch-American characters living in the late 1700s.

As with the 1934 cartoon, this portrait of Brom is at least in the ballpark of how Irving drew him: muscular, chummy, equestrian, and more shrewd and sly than brutal and boorish.

This movie debuted almost a decade after Disney studios dazzled audiences with the animation artistry of Fantasia, so it follows that it offers one of the greatest chase scenes of any film version. Interestingly, after that chase, the film never says or even hints that Brom might’ve been masquerading as the legendary phantom, allowing the audience to presume that the Headless Horseman was — well — the Headless Horseman. In an ending that feels a bit rushed compared to other versions, the audience learns that Ichabod disappeared, and despite a rumor that he settled elsewhere, the superstitious folk of Tarry Town prefer to think he was spirited away by their local decapitated demon.

Despite its spin on the finale, this version still has Brom wed Katrina, something that doesn’t happen in some of the films to follow. More to come.

— Tim

Click Here to Read aboutOther Screen Adaptations

of Irving’s Classic Work

October 15, 2025

Brom Bones on the Screen: The Headless Horseman (1922)

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

SubscribeOctober 8, 2025

The Scarlet Pencil: Dialing Down Dialect

The seventh volume of the Curated Crime Collection will feature all eighteen of Henry A. Hering’s wonderful stories about the Burglars’ Club. After running in Cassell’s Magazine, the first dozen tales were collected in a 1906 book titled The Burglars’ Club: A Romance in Twelve Chronicles. About five years later, Hering wrote six additional tales, and so far as I know, the full set has never been released as a book. That is—until my edition debuts, which I hope will be in a month or two.

I try to use a light hand when editing the Curated Crime books, but I’ve had to raise my hand to signal HALT! from time to time. While Hering uses a very modern language style—closer to the terseness of Hemingway than the “wordiness” of Dickens—his use of dialect can feel pretty clumsy by today’s standards. He does okay when it comes to, say, Cockney characters, but his German characters’ thick accents become downright annoying. This is partly because conventions for dialect have changed between the early 20th- and early 21st-centuries. Indeed, Hering is simply doing what many other writers of his era did. But it’s also because some of his ways to designate a German accent don’t make sense.

An illustration from Hering’s incomplete collection of Burglars’ Club adventures.Editing for Believability and Consistency

An illustration from Hering’s incomplete collection of Burglars’ Club adventures.Editing for Believability and ConsistencyFor instance, in “The Holbein Miniature,” Hering has Mr. Adolf Meyer ask Mr. Lucas what he thinks of when he looks out over the sea. The later says he thinks of boating and bathing, and Meyer then reveals himself to be a man of deeper thoughts:

Dat is where you islanders have the advantage over us treamers. But somehow the treams have a habit of outlasting de practice.... I tink of all dat is above it, and below it. On de top, ships carrying men and women and children to continents; below de waves, dead men and women and children, dose who have died by de way, floating by de cables which are carrying words dat make and unmake nations and men. Life and death are dere togedder.Th can be a difficult sound for those whose primary language doesn’t have that sound. Changing “there together,” to “dere togedder” makes for a believable accent (even though a “thin” and a “through” slip by elsewhere in Meyer’s dialog). But if someone can pronounce a d, why would that person turn “dreamers” into “treamers”? They probably wouldn’t. It’s simply a way to reinforce the character’s accent.

This accent-for-accent’s-sake approach can also seen when Meyers changes “photographs” to “photokraphs,” even though he is capable of putting the hard g into “Mein Gott!” And “prescriptions” becomes “brescriptions” even though Meyer can pronounce the b in “bekinning.” And “telescope” becomes “delescope” even though he seems able to pronounce all three t sounds in “shut my window tight.” Such dialect is inconsistent, which makes it unbelievable—which makes it a bit annoying. Look, Hering, I’m loving the story—and I get that the character is German—but if you’re koing to bersist in dransbosing letters, at least, stick to your kuns!

As I say, Hering is simply following dialect conventions of the early 1900s. I’ve seen the same in plenty of other pieces from that era’s fiction. It’s not a weakness. But it is an annoyance for fiction readers today, when the convention has become to gently remind readers of a particular accent. We’ll hear the accent in our imaginations, after all.

What’s more is Meyer, we’re told, has earned both an M.A. degree from London University and a Commander of the Royal Victorian Order from the British monarch. His English should be pretty good! Given these problems, I stepped in and converted everything this character says to standard English, all except for changing the th sounds to d sounds.

A Character Even More GermanA later tale, titled “The Truth Extorter,” introduces another German character. Dr. Bamburger doesn’t have nearly the same familiarity with English as Meyer, but his dialect is virtually the same. It also exhibits many of the same problems of believability and consistency:

Dere is a patch of prown, but not as big or as dark as I should haf expected...Bamburger can’t say “brown,” but he can say “but” and “big”? Weird.

I vill not hand you to dem. Sit down; dat is all I want.Shouldn’t a character who turns “will” into “vill” also turn “want” into “vant”? And then Bamburger says “mitout” instead of “without.” Granted, the film term MOS or “mit out sound” allegedly sprang from a German director mispronouncing “without sound,” but turning w into v and afterwards into m — and elsewhere not doing anything at all with it—asks readers to juggle a lot.

In Bamburger’s case, I again made th sounds into d sounds and turned all w sounds into v sounds. This, I hope, is enough to suggest he has a thicker accent than Meyer along with granting readers’ imaginations the freedom to do the rest.

Despite my qualms about the dialect, I think Hering’s Burglars’ Club series has some really great storytelling in it! It’s engaging, funny, and seems to be saying something about the bored aristocrats who spice up their lives by burgling offbeat items from their almost-always aristocratic neighbors. I hope my dialing down the dialect will make a very enjoyable reading experience a little bit more enjoyable.

— Tim

(Posts identified as “The Scarlet Pencil” chronicle my meandering through the misty and mysterious quagmire of editing books.)

October 1, 2025

Byard’s Leap: The Winding History of a Single Bound

The legend of Byard’s Leap is as much about a heroic horse as it is about a horrible hag. I’ll try to summarize the narrative, even though — as we’ll explore — there are several variations on it.

Northwest of Sleaford, in Lincolnshire, England, is a spot known as Byards Leap. The curious name is a reference to a tremendous jump made by a horse once upon a time. You see, the local people were plagued by a nasty witch, one along the lines of, say, Black Annis, in that she lived in a cave, had long talon-like fingernails, and, some say, feasted on children.Luckily, a hero rose to vanquish the witch. At a nearby pond where horses gathered, he tossed a rock into the water to observe and select the steed with the quickest response time and/or with divine approval for the task at hand. The one he chose was named Byard (sometimes spelled Bayard or Biard).

The hero mounted Byard and rode off to confront the witch. There, a struggle began, and the witch dug her creepy fingernails into Byard. The poor horse lunged into the air and landed far, far away! In the process, the witch perished.

But the hoofprints left from Byard's Leap remain to this day. In fact, there are photos in this well-researched article written by Rory Waterman for the Lincolnshire Folk Tales Project.

As one expects, this legend evolved over time, different renditions swapping out specifics. I figured it might be interesting and hopefully useful to researchers if I were to dig up what I could on the printed history of the oral tradition. Below, then, is an informal annotated bibliography, chronologically ordered, of the Byard’s Leap narrative.

Tragically, no photograph seems to exist of Byard’s legendary leap (which suggests poor planning on the hero’s part). This substitute comes from Eadweard Muybridge’s Animals in Motion: An Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Progressive Movements (1899)Permutations Across Centuries

Tragically, no photograph seems to exist of Byard’s legendary leap (which suggests poor planning on the hero’s part). This substitute comes from Eadweard Muybridge’s Animals in Motion: An Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Progressive Movements (1899)Permutations Across Centuries1704: Anonymous, . This source is a travel journal purportedly written in 1704 and finally published in 1818. The unnamed author makes a quick reference to Byard’s hoofprints, which are “16 yards” apart. Knowing his readers might scoff at such a distance, the traveler teases: “But then, you must know, the horse was frightened by a witch, or perhaps he never leap so farr; and the people hereabouts keep the marke of the leap, on purpose to be seen.”

1776: William Stukeley’s Itinerarium Curiosum; Or, An Account of the Antiquities and Remarkable Curiosities in Nature and Art, Observed in Travels through Great Britain. Another travelogue, this one from the latter half of the eighteenth century, also refers to the spot. Stukeley writes: “[H]ere is a cross of stone, and by it four little holes made in the ground: they tell silly stories of a witch and horse making a prodigious leap, and that his feet rested in these holes, which I think rather the boundaries for four parishes….” Apparently, Stukeley didn’t know how to have fun.

1846: G. Oliver’s The Existing Remains of the Ancient Britons, Within a Small District Lying Between Lincoln and Sleaford. Oliver provides a much more detailed rendition of the legend. Here, we learn that “our witch was very cunning in the capture of children, which she carried to her cave and devoured.” Our hero is described as “A knight of tried courage, during the age of chivalry….” Our horse now jumps “at least 60 yards,” and does so three times.

1863: Edward Trollope’s “Lincoln Heath, and Its Historical Associations.” Though Trollope doesn’t mention any snacking on children, the witch here “was seen cowering over a fire emitting a blue unearthly light, and sometimes flitting bat-like through the shades of night, intent on mischief towards man and beast.” No precise yardage is mentioned, but “the witch’s claws deepen in the shoulders of the knight and the flanks of the horse; when happily the former calls to mind a cross road near at hand, and if he can but reach this he is safe. He pulls the left rein, therefore, and away bounds Bayard in that direction, until with one prodigious effort he clears the point of junction, and the witch falls dead before the leap is accomplished.” In other words, Byard’s mighty bound over a mystically powerful crossroad defeats the witchy foe.

1878: S.M. Mayhew’s “Welbourne, Lincolnshire, and Its Neighbourhood.” Now, the hero is something of a witch-hunter, one “whose mission appears to have been in delivering earth from sorcerers.” In his skirmish with the witch, Byard jumps three times, “each of about 170 feet.”

1891: J. Conway Walter’s “The Legend of Byard’s Leap.” Byard’s record is now set at “sixty feet,” and — replacing the knight — a “shepherd is selected for the enterprise” of defeating the witch. This revision makes the hero a much more humble one — instead of Bruce Wayne, he’s Peter Parker (before the big bite!) — and this builds tension, given his inexperience with slaying stuff. Also, unless I missed something, this is my first source that says Byard is blind, and Walter explains that this is “a providential circumstance, since it is likely that any horse which could see would shrink from contact with the witch.” Instead of a deadly crossroad, the witch falls off Byard and down into a pond, where she drowns. Witches and water have an uneasy history.

1895: Sidney Oldall Addy’s “25–Byard’s Leap.” As with Walter, the hero shifts from a gallant knight to an ordinary bloke, specifically, one of the local farmers. Byard is once again blind. That horse’s three leaps now measure “seven yards.” A simple knife wound costs the witch her powers, though perhaps not her life. I like to think she found a new career as a manicurist.

1904: M.P.’s “63. Bayard’s Leap and the Late Canon Atkinson’s View of the Legend.” M.P.’s goal is to establish the earliest known version of the ever-evolving tale. The witch is back to eating people and residing in a cave, and the hero is back to being a wandering knight. There’s a quick note that the special horse was “sometimes called the blind Bayard,” and another one about versions disagreeing about whether the horse jumped three times or only once. Here, the witch dies from the knight’s sword.

Reboots Are Nothing NewI’m sure there are more transcriptions of the legend out there, but this is enough to suggest how it morphed over time. What makes the witch so dreaded? Who slays her, and how does she die? Is Byard blind or not? These are questions different narrators answer differently. Nonetheless, the story retains its essentials: a bad witch, a brave hero, a chosen horse, a deep stab, a mighty leap, and a dead witch. Oh, and holes in the ground to “prove it.”

In fact, the legend continues to take on new forms. None of the sources above provides a name for the witch, but these days, you’ll find her called Old Meg or Black Meg. The former is found in this version along with a full backstory for her, one in which the conquering knight is her former sweetheart — and really quite a jerk!

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.

September 15, 2025

Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit: A Headless Ghost Near Stillwell, Indiana

The Farmer Who Became a Railroad Ghost

The Farmer Who Became a Railroad GhostThis case isn’t exactly a railroad haunting. Not at first, anyway. Instead, it transformed into one in under two years.

To understand this, we need to look back to November 14, 1903. On that day, an Indiana farmer named Columbus Cole was using a steam-driven machine to process a corn harvest. The boiler exploded, killing Cole and injuring those working alongside him. The next day, The Indianapolis Journal reported that the tragedy occurred “four miles south of Stillwell, Laporte County.” The next week, the Walkerton Independent specified that the accident took place “on the Flaherty farm at the Kankakee river.” The fact that Cole died at the Flaherty farm will become important in a moment.

For now, we should note that both papers describe Cole’s death very similarly. The Journal states: “top of head blown off and body mangled.” The Independent explains that the explosion caught Cole, “tearing off a portion of his head and killing him instantly.”

In August of 1905, a ghost identified as Columbus Cole was observed. Now, however, his head was completely missing, and the remainder of his form was said to haunt the platform of a train depot. The figure even gave signs of trying to signal a train. In other words, over time — and not much time — the case had become a railroad haunting.

The Richmond Planet report on Columbus Cole’s ghost makes many mistakes, as discussed below, but this illustration is pretty cool. I especially like the two gents who seem mildly concerned about what they’re seeing.Fast Folklore and Rotten Reporting

The Richmond Planet report on Columbus Cole’s ghost makes many mistakes, as discussed below, but this illustration is pretty cool. I especially like the two gents who seem mildly concerned about what they’re seeing.Fast Folklore and Rotten ReportingOn August 12, 1905, Virginia’s Richmond Planet made some mistakes. Relating the ghost story, it says the haunting was occurring in Flaherty, Indiana. There is no Flaherty, Indiana. They add that citizens of Flaherty have been avoiding “Flaherty station” each night, since that’s where and when the ghost manifests “on the platform.” Hold on now. There might have been a siding — a stretch of side track where a train can sit while another passes or where cars might be stored and shuffled around — and this siding might have been near or on the Flaherty farm. But even this is iffy. There almost certainly was no station with a platform there, though the Lake Eire & Western line had scheduled stops at nearby Walkerton, Kankakee, and Stillwell. (It’s possible that the Kankakee stop was called “Flaherty” by the locals, but I’ve found no evidence that there was ever a structure there as depicted in the illustration above.)

The subtitle of the Planet article even compares the ghost to a railroad worker: “Appears in Attitude of Switchman Flagging a Train.” If readers don’t know that Cole was killed by farm machinery, they’re likely to picture a steam locomotive when reading that he “lost his head years ago in a boiler explosion.” Not years exactly. Closer to 21 months. But folktales prefer hazy “once upon a time” settings.

A different ghost report appeared a couple of days later in New Haven, Connecticut’s Morning Journal and Courier. Here, the ghost is said to haunt, not the station platform, but “the old water tank by the station on the Lake-Erie Railway at Flaherty’s Slinding.” It’s next spelled “Sliding,” but I assume they mean “siding.” Oh, but things get even worse. We read that Cole

was run over by an engine within a few feet of the spot where the water tank stands. In the accident his head was completely severed from his body. At the time the body, after being decapitated, stood erect and walked several feet from the spot. After emitting a terrible shriek, it fell against the water tank.I’m not sure how a man with his head blown off is able to stumble and shriek — but I bet it’s a darned unpleasant experience for all involved. Can we blame the reporters? Sure, but I have a hunch the tragic death of Columbus Cole had inspired the locals to tell grisly, if not outright fantasy, folk stories about the event. Along the way, that man’s headless phantom had ambled from an actual farm toward a non-existent railroad station. This, then, is what the reporters were reporting.

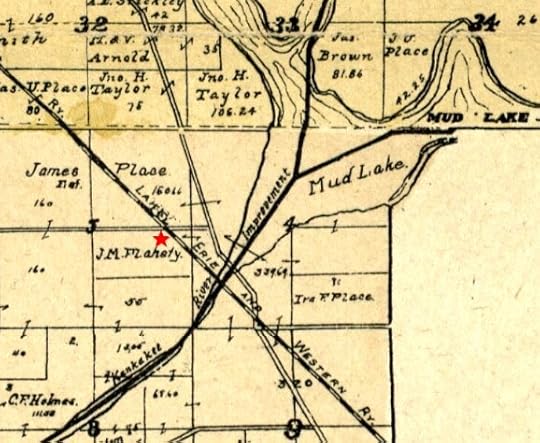

Locating the Farm and the Tracks NearbyWhere the Flaherty farm once was is easily pinpointed. agrees pretty well with the Journal article: it was about four miles southeast of Stillwell. Zoom in on that map, follow the Lake Eire & Western line down, and you’ll spot the land just northwest of where the tracks cross the Kankakee River. Indeed, those tracks cross the Flaherty farm, too, which begins to explain how the ghost became associated with the railroad.

I put a red star to help locate the Flaherty farm on this (1901).

I put a red star to help locate the Flaherty farm on this (1901).Google Maps suggests those tracks north of the river are still in place — but it’s tricky to decide how to launch a search for the headless ghost. State Road 104 comes close to the general area. Still, does a paranormal investigator try to reach the farm, where the death occurred? Or examine the tracks, where the ghost reports imply the specter walked? Are there any rusty remains of a water tank? Assuming one can legally and safely roam the area, a nice bit of roaming would seem to be required.

If you do accept the challenge, please let us know about your experience in the comments.

Discover more “Railroad Hauntings You Can Still Visit” at the page forAfter the End of the Line: Railroad Hauntings in Literature and Lore.

September 10, 2025

Haunted Ancestral Homes 13: The Mysteries of Hinton Manor

This article comes from the February 2, 1892, issue of the Ripon Reporter. It was among of a reprint of Frith’s series.

As Frith explains, Hinton Manor (a.k.a. Hinton Ampner) no longer stands. For a fuller account of the haunting and Jervis and Luttrell’s investigation of it, please read the “Purposeless Ghosts: Jervis, Bolton, and Luttrell at Hinton Ampner” chapter in Certain Nocturnal Disturbances: Ghost Hunting Before the Victorians. In the meantime, you might enjoy my post about four prominent cases of a haunting being substantiated by the claim that skeletal remains were unearthed there. It became a minor motif in the Victorian-era ghost reports.

Back to the Preview of the SeriesIf you’re intrigued by Victorian ghostlore, consider purchasing The Victorian Ghost Hunter’s Casebook. It features fourteen firsthand chronicles of actual ghost hunts.Click on the cover to learn more.

September 8, 2025

Speculation on How and Where Dr. Watson Published His Holmes Chronicles, Part Two

Having now read The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893-94), The Hound of the Baskervilles (1901-02), and The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1903-04), I have little to report regarding my quest to find out how and where Dr. Watson (as opposed to Arthur Conan Doyle) might have published his narratives about the great detective. If anything, that rascally Conan Doyle seems to have inched away from providing me any clues. Let’s take a glance at what little there is, and then I’ll toss around an idea or two regarding the author’s attempt to kill off his most famous creation.

Sidney Paget’s illustration of Watson and Holmes for “The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual,” published in The Strand Magazine and later collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

Sidney Paget’s illustration of Watson and Holmes for “The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual,” published in The Strand Magazine and later collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock HolmesThe Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

“Silver Blaze”

Holmes: “…I made a blunder, my dear Watson — which is, I am afraid, a more common occurrence than anyone would think who knew me through your memoirs.”

“The Yellow Face”

Watson: “In publishing these short sketches based upon the numerous cases in which my companion’s singular gifts have made us the listeners to, and eventually the actors in, some strange drama, it is only natural that I should dwell rather upon his successes than upon his failures.”

“The Gloria Scott”

Holmes [after recounting an investigation he handled before meeting Watson]: Those are the facts of the case, doctor, and if they are of any use to your collection, I am sure that they are very heartily at your service.”

“The Musgrave Ritual”

Watson [regarding Holmes’ occasional “outbursts of passionate energy”]: “…as I have mentioned somewhere in these incoherent memoirs…”

Holmes [regarding his early cases]: “Yes, my boy, these are all done prematurely before my biographer had come to glorify me.”

Holmes [to Watson]: “But I should be glad that you should add this case to your annals….”

“The Reigate Squires”

Watson [regarding a case “too recent in the minds of the public” and too heavy in politics and finances]: “…to be fitting subjects for this series of sketches.”

“The Crooked Man”

Holmes: “…the effect of some of these little sketches of yours…”

“The Resident Patient”

Watson: “Glancing over the somewhat incoherent series of Memoirs with which I have endeavoured to illustrate a few of the mental peculiarities of my friend Mr Sherlock Holmes, I have been struck by the difficulty which I have experienced in picking out examples which shall in every way answer my purpose… [Some illustrate Holmes’s brilliant reasoning but the facts of the case are so dull] that I could not feel justified in laying them before the public…. [That brilliance isn’t highlighted in this case, but] the whole train of circumstances is so remarkable that I cannot bring myself to omit it entirely from this series.”

“The Greek Interpreter”

Mycroft Holmes [to Watson]: “I hear of Sherlock everywhere since you became his chronicler.”

“The Naval Treaty”

Watson [after mentioning three cases “recorded in my notes”]: “The first of these, however, deals with interests of such importance and implicates so many of the first families in the kingdom that for many years it will be impossible to make it public…. The new century will have come, however, before the story can be safely told.” [Instead, he narrates the second investigation.]

“The Final Problem”

Watson: “It is with a heavy heart that I take up my pen to write these the last words in which I shall ever record the singular gifts by which my friend Mr Sherlock Holmes was distinguished.” [Holmes, you see, dies at the end of this case. Luckily, his condition improves afterward.]

The Hound of the Baskervilles

By the fireside on a “raw and foggy night” in late November, Holmes recounts the terrible tale of a gigantic — and possibly spectral — pooch.

By the fireside on a “raw and foggy night” in late November, Holmes recounts the terrible tale of a gigantic — and possibly spectral — pooch.Watson: “…I had often been piqued by his indifference to my admiration and to the attempts which I had made to give publicity to his methods.”

Stapleton [to Watson]: “The records of your detective have reached us here [in rural Devon], and you could not celebrate him without being known yourself.”

Watson: “So I have been able to quote from the reports which I have forwarded during these early days to Sherlock Holmes. Now, however, I have arrived at a point in my narrative where I am compelled to abandon this method and to trust once more to my recollections, aided by the diary which I kept at the time.

The Return of Sherlock Holmes

“The Norwood Builder”

Watson: “[Holmes] bound me in the most stringent terms to say no further word of himself, his methods, or his successes — a prohibition which, as I have explained, has only now been removed.”

Holmes: “Perhaps I shall get the credit also at some distant day when I permit my zealous historian to lay out his foolscap one more — eh, Watson?”

“The Solitary Cyclist”

Watson: “As I have preserved very full notes of all these cases, and was myself personally engaged in many of them, it may be imagined that it is no easy task to know which I should select to lay before the public…. I will now lay before my reader the facts connected with Miss Violet Smith…. [T]here were some points about the case which made it stand out in those long records of crime from which I gather the material for these little narratives.”

Watson: “In the whirl of our incessant activity it has often been difficult for me, as the reader has probably observed, to round off my narratives, and to give those final details which the curious might expect…. I find, however, a short note at the end of my manuscripts dealing with this case, in which I have put it upon record that Miss Violet Smith did indeed inherit a large fortune….”

“The Six Napoleons”

Holmes: “If ever I permit you to chronicle any more of my little problems, Watson, I foresee that you will enliven your pages by an account of the singular adventure of the Napoleonic busts.”

“The Three Students”

Watson: “It will be obvious that any details which would help the reader to exactly identify the college or the criminal would be injudicious and offensive. So painful a scandal may well be allowed to die out.”

“The Missing Three-Quarter”

Watson: “Young Overton’s face assumed the bothered look of the man who is more accustomed to using his muscles than his wits; but by degrees, which may repetitions and obscurities which I may omit from his narrative, he laid his strange story before us.” [Watson then provides an edited transcription of what Overton narrated.]

“The Abbey Grange”

Holmes: “…I must admit, Watson, that you have some power of selection which atones for much which I deplore in your narratives. Your fatal habit of looking at everything from the point of view of a story instead of as a scientific exercise has ruined what might have been an instructive and even classical series of demonstrations. You slur over work of the utmost finesse and delicacy in order to dwell upon sensational details which may excite, but cannot possibly instruct, the reader.”

“The Second Stain”

Watson: “I had intended ‘The Adventure of the Abbey Grange’ to be the last of those exploits of my friend, Mr Sherlock Holmes, which I should ever communicate to the public. This resolution of mine was not due to any lack of material, since I have notes of many hundreds to cases to which I have never alluded, nor was it caused by any waning interest on the part of my readers in the singular personality and unique methods of this remarkable man. [The reason is positive publicity helped Holmes while he was active, but now that he’s retired,] notoriety has become hateful to him…. [Holmes allows Watson to publish this narrative to fulfill a promise and to illustrate] the most important international case which he has ever been called upon to handle. [However, it is] a carefully-guarded account of the incident…. If in telling the story I seem to be somewhat vague in certain details the public will readily understand that there an excellent reason for my reticence.

“The Abbey Grange” repeats one of Holmes’ complaints about Watson’s chronicles that he’d been making from the start: his biographer prefers to tell a ripping yarn rather than elucidate a lesson in crime-solving. However, when Holmes jumps out and says “Boo! I survived Reichenbach!” at the start of The Return, Watson grows more than hitherto concerned with 1) drawing from his extensive records and 2) protecting the identities of persons or institutions involved therein. None of this, however, offers us a clue of where Watson sent his manuscripts for publication.

I’m hesitant to point to The Strand Magazine as the journal in which the Holmesverse public read Watson’s chronicles. As mentioned last time, The Strand is not mentioned at all in the canon, and why Conan Doyle’s name is on them in that publication is befuddling. In Hound, Watson cites the Devon Country Chronicle, which seems to exist solely in the Holmesverse, not in, well, wherever it is The Strand exists. The Doyleverse? The Ourverse? Therefore, I have a hunch Watson published in a journal that isn’t available to you or me. We do know from “The Second Stain” that it was a journal with a solid readership, since the great detective’s popularity was unfailing. This is about as good a clue as Conan Doyle gives: Watson got his stuff published in such a way that it became and remained well-known.

A Few Thoughts on Holmes ResurrectedI suspect a lot of my readers already know that Conan Doyle pushed — well, nudged — Holmes and Moriarty off Reichenbach Falls in “The Final Problem,” the last story in Memoirs. He subsequently wrote Hound, but he set it prior to that fateful plunge. I’ve read biographers say Conan Doyle had grown sick and tired of Holmes, and he did the terrible deed to be free to focus on other writing.

And yet, an anecdote Conan Doyle share in the 1920s suggests he retained a fondness for his famous detective — or, at least, recognized that the tales were worth retelling. By this decade, Conan Doyle had reinvented himself as a global advocate of Spiritualism, and in Our Second American Adventure (1924) he recounts spreading the word across North America. While passing through Los Angeles, the famous author met a famous child star — and later Uncle Fester — Jackie Coogan. Conan Doyle writes:

They asked me to be photographed with [Coogan], so I employed the time telling him a gruesome Sherlock Holmes tale, and the look of interest and awe upon his intent little face is an excellent example of those powers which are so natural and yet so subtle.Clearly, Conan Doyle hadn’t abandoned Holmes completely. In fact, if the situation called for it, he entertained a kid with one of the old cases.

Allow me to suggest, then, another motive for Conan Doyle sending Holmes down the waterfall when he did: the author, cranking out new cases each month, was struggling to invent suitable mysteries. Some of the tales in Memoirs feel different from those in Adventures and the first two novels, especially “The Yellow Face” and “The Gloria Scott.” While Holmes and Watson get involved in these mysteries, they look on from a bit of a distance as things resolve themselves. It’s as if Conan Doyle was squeezing his series characters into independent tales that would’ve been about as good without them.

Memoirs also reveals Conan Doyle starting to repeat himself. “The Stockbroker’s Clerk” isn’t all that different from “The Red-Headed League” in that a person is hired to perform a kooky job as a diversion for robbery. Now, I very much enjoy Hound, but it seems like an elaboration on “The Copper Beeches,” given the Gothic mansion and the ravenous dog. Part of the problem, I admit, is the fact that I’m reading these works within a span of weeks, not of months or years, as did the original readers. Still, this approach might permit glimpses into Conan Doyle’s head that wouldn’t otherwise be available.

Ah well. Slow and steady solves the mystery. More to come.

Part Three is forthcomingSeptember 4, 2025

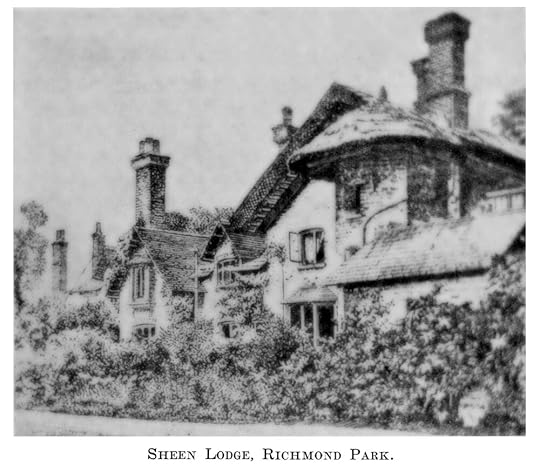

In the Footsteps of Athenodorus: Sir Richard Owen’s Probably Not True Ghost Story

Sir Richard Owen (1804-1892) was an anatomist and paleontologist whose work shaped how we talk about dinosaurs. Despite his interest, Owen opposed Darwin’s ideas on evolution, though this might have been kindled by professional jealousy. Still, he was part of a long tradition of important scientists — Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton among them — who studied the natural world in order to illuminate God’s handiwork.

It’s interesting, then, that a ghost story told about Owen, one which would confirm the existence of the human soul beyond death, is probably not true. You see, though there’s a clever spin, the story is suspiciously close to the ancient legend of Athenodorus found in the letters of Pliny the Younger. (There’s a nice 1879 translation here.) Briefly, that very old tale goes like this:

Athenodorus came upon a house reputed to be haunted. Intrigued, he arranged to stay there. He spent his first night awake, focusing on his writing to ensure he wouldn't be misled by expectations of ghostly activity. Just the same, a creepy ghost appeared, bidding Athenodorus to follow him. After a short stroll to the back, the ghost sunk into the ground. At this very spot, the next day, Athenodorus unearthed shackled human bones! When the skeleton was reinterred with proper ceremony, the ghost never again appeared.Augustus Jessop, who offers his own translation of Pliny’s Athenodorus legend, mentions that the tale “is a specimen of the kind of ghost story which is very commonly repeated when such stories are going the round.” Indeed, I’ve found a few variations of it in Victorian ghostlore among reports that employ skeletal remains to support the reality of a haunting.

The Owen RevisionAt least in terms of the Owen story being told in newspapers, things seem to start with the June 18, 1893, issue of The San Francisco Chronicle. This article is attributed to Alan Owen, whose surname suggests some sort of relation to the scientist. However, my cursory search has provided no proof of such a connection. From San Francisco, the newspaper piece traveled east to places including Utah, Minnesota (shown below), and even Newcastle, England.

There are some nice details added, but the parallels between this and the Anthenodorus legend are striking: reports of a ghost, an investigator whiling his time by writing, the ghost leading that investigator to its hidden skeletal remains, and those remains receiving a long-overdue hallowed burial.

A Lack of Hard BonesI’ve found little to suggest this report is anything more than a tall tale concocted by “Alan Owen.” Granted, Richard Owen did live at Sheen Lodge. According to one bibliography, he “told excellent ghost stories” — though this is prefaced by saying he himself was without “the least superstition.” I have yet to find any evidence that the scientist ever told this particular story. And I fear my chances of contacting that unnamed rector or the unnamed son of the unnamed sexton are very, very slim.

From a 1911 issue of the John Hopkins Hospital Bulletin.

From a 1911 issue of the John Hopkins Hospital Bulletin.All I’m left with, then, is another Athenodorusesque story to add to my collection of old ghost reports that use skeletal remains to substantiate a haunting, a topic I discuss here. I also discuss Athenodorus, the earliest inductee into The Ghost Hunter Hall of Fame, here.

— Tim