LAND IS ALL THAT MATTERS: THE AUTHORS CUT 3

THE AMERICAN JOURNALIST

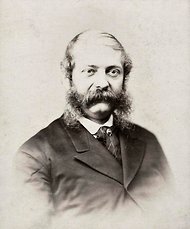

William Henry Hurlbert under coercion

William Henry Hurlbert

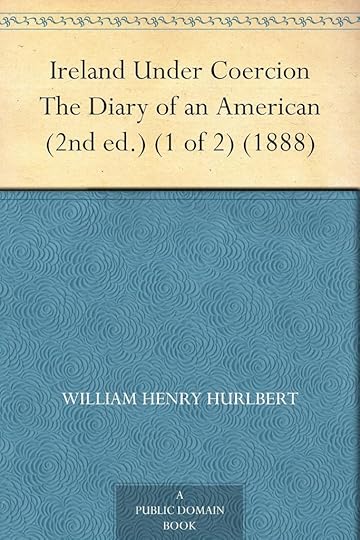

Sightings of the Lesser-Spotted American Journalist (auctor Americanus) in Land War Ireland were so frequent as to be without scarcity value. Most (Henry George, James Redpath) came down firmly, or gently, on the side of the Irish tenant. This is what makes the observations of William Hurlbert, one-time editor of the New York World, more provocative. He took the opposite tack to most of his fellow American scribes during the Second Land War. He was described by Michael Davitt (whom he interviewed in 1888) as ‘a coercionist chronicler for Mr. Balfour’[1] and clearly set out his stall in the introduction to his narrative, the two-volume Ireland Under Coercion: The Diary of an American, published in 1888.

The class war between the tenantry and their landlords … which is now undoubtedly waging in Ireland, cannot be attributed to the historical grievances of the Irish people. The tradition and the memory of these historical grievances may indeed be used by designing or hysterical traders in agitation to inflame the present war. But the war itself … has the characteristics no longer of a defensive war, nor yet of a war of revenge absolutely, but of an aggressive war, and of a war of conquest.[2]

Given their experience of crusading American journalists ‘going native’ and siding with tenant against landlord, the leadership of the National League must have wondered what they had done to deserve the attentions of William Henry Hurlbert.

The most obvious question prompted by William Henry Hurlbert’s employment of a literary wrecking ball in his coverage of the Second Land War, aka the Plan of Campaign is: did he begin his journalistic quest (if indeed it can be described as such) with certain pre-conceptions, or is his work based on observation and an ex post facto assessment of what he witnessed? Was his mind made up before he started, or was it still open to argument and observation?

Most Irish nationalists firmly believed that Hurlbert’s cards had been marked well in advance of his arrival in the country, either by self-interested champions of Tory policy or by his own innate political prejudices. Davitt asserted that Hurlbert’s anti-Plan malice derived from an earlier failure to obtain Irish nationalist support in a bid to secure a posting as US ambassador to London. It also had a clear ideological basis. The socialist dogma of his fellow (and more successful) New York-based journalist, Henry George, was anathema to the politically conservative Hurlbert. In his introduction to Ireland Under Coercion, the former New York World editor fulminated against George’s creed of land nationalisation, describing it as ‘confiscation’ and going on to compare George’s template to the manner in which ‘the State proceeded against the private property of rebels and traitors’.[3]

Henry George

That he came from a staunch ‘Dixie’ Protestant family (he had a brief stint as a Unitarian minister) may have coloured his attitude to Irish Catholic nationalism and its tributary agrarian campaigns. But Hurlbert was not necessarily philosophically entrenched and incapable of changing his mind. Take his very name, for example. He was born William Hurlbut in Charleston, South Carolina in 1827 and was educated at Harvard. However, when a printer made a mistake in creating a business card—designating him as ‘Hurlbert’—instead of insisting that the offending objects be immediately immolated, he was so taken with the misprint that he changed his name in accordance with the error. Despite his birth in the ‘deep South’, he was an opponent of slavery, albeit he was an anti-slavery Democrat rather than a Lincoln-supporting Republican. After a lifetime of bachelordom, he obviously reconsidered his position on connubial bliss and married at the advanced age, even for a bridegroom, of fifty-seven. Neither, while on his Irish travels, did he exclusively seek out the sort of opinions he seems to have most wanted to hear. Although it is clear from his narrative that he preferred the company of landlords, like Richard Stacpoole in Clare and Charles Ponsonby in Cork, he also sought out the views of Michael Davitt and the fiery Donegal priest, Father James McFadden.

The title of the work derived from his visit to Ireland might suggest to the unwary that Hurlbert was completely ad idem with his journalistic compatriots from the First Land War, otherwise why highlight the word ‘coercion’ in the title? However, Hurlbert, in his use of this freighted codeword is not referencing the stringent provisions of Balfour’s Crimes Act, but the intimidatory tactics of the Irish National League and its local enforcers. United Ireland described Hurlbert’s work as ‘libellous’ and ‘fit to take its place amongst other grotesque foreign commentaries’.[4] To that sublime journal of the British establishment, The Times, however, fresh from its own ‘Parnellism and Crime’ accusations of thuggery against the Irish party leader and his associates, it was ‘entertaining as well as instructive’.[5]

Hurlbert’s work is exhaustive (two volumes and 653 pages in length) and highly partisan. He includes masses of minute polemical detail—amounts held in savings accounts in banks located near Plan estates, or the (scarcely relevant) number of public houses in the main urban centres of County Clare—but his twin tomes are also clearly influenced in style by gossipy contemporary travellers’ tales. With an eye to a more commercial market, he frequently branches off into detailed descriptions of some of the exquisite landscapes through which he travelled.

The first ‘tell’ when it comes to the political slant of Ireland Under Coercion (after his combative introduction) is his account of a visit to Balfour within hours of his arrival in Dublin in late January 1888. The chief secretary was in ‘excellent spirits’ and displayed much of the nonchalance that consistently aggravated the native antagonism of nationalist politicians towards him. Hurlbert opines, tongue affixed in cheek, that Balfour was ‘certainly the mildest-mannered and most sensible despot who ever trampled in the dust the liberties of a free people’.[6] From the bourn of that ironic swipe—within the first twenty pages of the opening of Volume One—there was no possibility of return for this traveller. It may even have been the case that Hurlbert arrived in Ireland with an entirely open mind and left Dublin Castle charmed by the affable side of Balfour’s nature. If so, his subsequent failure to secure an early balancing interview with Davitt in Dublin might have compounded his hostility to the Plan. He eventually tracked down Davitt in London and conducted an oddly ‘soft focus’ interview that seems to have had as much to do with the latter’s commercial schemes—the development of a wool export business and the opening of granite quarries in Donegal and Mayo—as it did with the renewed agrarian conflict, in which, of course, Davitt was not directly involved. Hurlbert did not include in his itinerary any of the acknowledged leaders of the Plan. He did, however, as noted above, interview and accept the hospitality of a number of the major landlord targets of Plan activists.

It is impossible to encapsulate a work of more than 600 pages in a few paragraphs but it is worthwhile highlighting Hurlbert’s visits to Donegal and Clare, and his treatment of two assertive Roman Catholic priests, Father James McFadden, parish priest of Gweedore, and Father Patrick White, parish priest of Milltown Malbay. He appears to have developed a considerable rapport with McFadden, despite their obvious ideological differences. White he did not meet in person, but his account of the latter’s activities caused the priest to threaten Hurlbert with a libel suit.

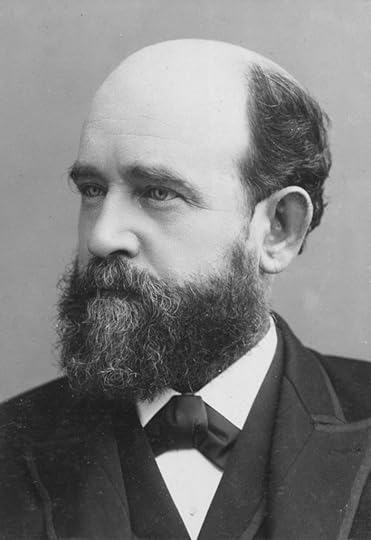

Fr. James McFadden of Gweedore

James McFadden was forty-six years of age in 1888. He was a thick-set, bulldog-like man from a comfortable family background with a very sure sense of his own importance (‘I am the law in Gweedore’[7]) and a history of loyalty to agrarian causes stretching back to his involvement with the Land League. McFadden had been radicalised as a witness to the activities in Donegal of those two notorious evicting landlords, William Sydney Clements, 3rd Earl of Leitrim (murdered by his tenants in 1878) and John George Adair (responsible for the Derryveagh mass evictions in 1861). In 1880 McFadden had also been witness to a much-publicised tragedy when five of his parishioners drowned after a flash storm flooded the Gweedore church in which he was saying mass. McFadden himself managed to escape death only by jumping from the altar through a closed window. McFadden did not brook dissent or opposition from his parishioners and was known locally, in suitably hushed tones, as ‘An Sagart Mór’ (The Big Priest) despite his small stature.

In the year of Hurlbert’s visit to Gweedore, McFadden spent six months in jail in Derry for a seditious speech and for organising boycotts and a rent strike—the initial sentence had been three months but was doubled on appeal. In 1889 he would be at the centre of a far more serious episode when an attempt by an RIC Inspector, William Martin, to arrest him after Sunday mass on 3 February, resulted in a number of McFadden’s parishioners beating Martin to death. McFadden was among those charged with murder arising out of the killing but was allowed to plead guilty to the lesser offence of obstruction of justice. At which point McFadden’s bishop intervened and moved him to a new parish out of harm’s way and banned any further involvement by the priest in agrarian activity.

But that controversial tragedy was in the future when Hurlbert arrived in Gweedore, one of the most immiserated parts of an impoverished county, in early 1888. Most of the land in the area had been acquired in 1838 by Lord George Hill, an improving landlord (with all the negative as well as positive connotations of that designation). In 1845, just as the Great Famine was about to take hold, Hill published a self-regarding memoir, Facts about Gweedore, which outlined many of the changes he had brought about in the area. These included the acquisition of almost half of his estate land for his own purposes. This was a regular feature of landlord ‘improvement’ and was bitterly resented by evicted or potential tenants who were obvious losers in such scenarios. In 1889 McFadden published a riposte entitled The Present and the Past of the Agrarian Struggle in Gweedore, in which he ridiculed Hill’s book as a publication, ‘which might, perhaps, with more regard to truth and accuracy be called ‘Fictions from Gweedore’.[8] The parish priest claimed that the landlord’s ‘improvements’ had failed to benefit anyone but himself. Hill died in 1879, as the First Land War was gathering force in Mayo. In 1888 the Gweedore land, an estate of 24,000 acres, was owned by Hill’s heir, Captain Arthur Hill.

Lord George Hill

In a letter to the Derry Journal in September 1887, McFadden threw down the gauntlet to Captain Hill, twitting the latter with the observation that ‘he may, by the aid of his Winchester repeater and a Coercion government, hope to make gold from granite, but it takes little fore-knowledge to prophesy that the effort will fail him’.[9] McFadden proved a determined and energetic adversary for Hill and the RIC. He appears to have had little in common with the aristocratic Hurlbert, yet, when they met, the two men got on famously, with the American journalist enjoying the hospitality as well as the company of the turbulent priest.

Hurlbert’s initial assessment of McFadden was of a man with ‘great freedom and fluency … sanguine by temperament, with an expression at once shrewd and enthusiastic, a most flexible persuasive voice.’ McFadden laid the blame for the problems in Gweedore and neighbouring Falcarragh (where the troubled estate of Wybrants Olphert was located and where the protective RIC complement had been raised from six to forty) not at the door of the landlords, but at their agents. Because, the priest observed, the land agents were paid by commission based on the amount of rental money actually collected, ‘the more they can screw either out of the soil, or out of any other resources of the tenants, the better it is for them’.

In the course of their conversation, McFadden made one startling concession to Hurlbert. He acknowledged that, even if the tenants themselves owned the land they were working, not all of them would be able to live off their holdings. The admission, of itself, was hardly more than a pragmatic assessment of the economics of subsistence farming in Donegal from a man rooted in reality. The surprising element is that he would have been so candid with a visiting correspondent such as Hurlbert. Clearly the latter had not tipped his hand to the priest, who would also have been aware that much of the income earned in the remoter parts of Donegal did not come from subsistence farming but from the fruits of seasonal migration.

McFadden did, however, offer a solution to the conundrum. Government investment in land reclamation, he claimed, would enable more tenants to make a decent living from their holdings. ‘The district could be improved’, he continued, ‘by creating employment on the spot, establishing factories, developing fisheries, giving technical education, and encouraging cottage industries.’ In outlining this plan, McFadden was anticipating the Congested Districts Board, one of the staging posts in the Conservative government’s strategy in the 1890s of ‘killing Home Rule with kindness’ – creating a contented peasantry (while still maintaining landlord supremacy) that would forswear grievance politics and abandon the cause of legislative independence in favour of enjoying and augmenting their newly acquired creature comforts. (Spoiler alert – it didn’t work.)

As the conversation wound down, Hurlbert tackled McFadden on what he may have perceived as the cleric’s weak spot: the issue of a priest encouraging his flock to ignore the moral responsibility to pay their rent. McFadden, who must have anticipated the question, had his response well-prepared: ‘If a man can pay a fair year’s rent out of the produce of his holding, he is bound to pay it. But if the rent be a rack-rent, imposed on the tenant against his will, or if the holding does not produce the rent, then I don’t think that is a strict obligation in conscience’.

In the case of Gweedore, McFadden was, essentially, making the point that a tenant should not be obliged to subsidise his own rent from income derived while working as a farm labourer in Scotland or elsewhere. Hurlbert demurred, citing the United States as his precedent, and noting that: ‘If a tenant there cannot pay his first quarter’s rent (they don’t let him darken his soul by a year’s liabilities) they promptly and mercilessly put him out’.[10]

The interview at an end, Hurlbert rose to go, but before his departure he was offered ‘a glass of the excellent wine of the country’. Since nineteenth century Irish viticulture was sparse, this might well be taken as a sly reference to the local poitín (poteen). However, McFadden was as much of a thorn in the side of the local illicit distillers as he was of landlords, having waged a dogged campaign against local poteen-makers. Interestingly, the priest declined to join his guest in his own hospitality, pleading that he was ‘almost a teetotaller’. Hurlbert was later advised that it was Captain Hill’s refusal of a similar offer of hospitality that sparked the quarrel with McFadden. This was a classic example of Irish reductionism. There was rather more at issue between priest and landlord than a glass of contraband ‘uiscebaugh’.

Ballyconnell House, Falcarragh, Co. Donegal

Hurlbert’s next host was Wybrants Olphert of Ballyconnell House in nearby Falcarragh. This was an altogether different experience for the American journalist. Before he sat down to lunch with the Falcarragh landlord, Hurlbert noticed the man’s son enter the house and toss a revolver on the hall table, prompting the American to make comparisons with the ‘Wild West’. While McFadden had blamed the landlords’ agents (Hewson and Dopping) for the local unrest, Olphert did not reciprocate the courtesy. He held McFadden, and the Falcarragh curate, Father Daniel Stephens, largely responsible, along with his younger tenants, for the annoyance being visited upon him. Olphert was especially aggrieved because he had agreed to a 20 per cent reduction in rent and insisted to Hurlbert that there had been no evictions on his estate. That situation would soon change, and with a vengeance. In January 1889 Olphert dug in his heels, and Hewson began a series of ejectments that continued for two years. By December 1890 more than 350 families had been evicted, and only 10 per cent were readmitted to their holdings.[11]

In his account of his conversation with Olphert, Hurlbert introduced a trope to which he often returned over the next 500 pages of Ireland Under Coercion, namely the question of the ability of supposedly immiserated tenants to pay their rent. Hurlbert’s thesis was that Plan tenants were agitators with a political agenda, as opposed to subsistence farmers no longer able to pay even arbitrated rents because of continued agricultural depression. In a series of QED moments throughout the book, he makes reference to the total amounts held in Post Office savings accounts in areas where the Plan was at its most belligerent. The implication was that the very existence of savings accounts indicated a considerable degree of local prosperity and that the money being squirrelled away belonged to tenants who should have been remitting it to their landlords, a somewhat dubious line of logic. Hurlbert also made frequent reference to substantial increases in the level of banked savings in the course of the 1880s.

For example, in the case of Falcarragh he observed that the Olphert tenants ‘are not going down in the world’ because bank deposits that stood at £62.15s in 1880 had risen to £494.11s in 1887.[12] In the second volume of his work he makes a similar argument regarding Sixmilebridge in County Clare, Killorglin in County Kerry, and Gorey in County Wexford.[13] However, he offers no evidence that local tenant farmers were the beneficial owners of the bulk of those savings accounts. Neither does he take into consideration the sums being saved by Plan adherents in rent which were being banked locally by the trustees of the fighting funds. This might well account for at least some of the increases noted between 1880 and 1887.

Hurlbert’s visit to Gweedore and Falcarragh took place in early February 1888. Towards the end of that month, he found himself in County Clare, often accompanied on his travels there by Resident Magistrate Colonel Alfred Turner, who, arguably, had more sympathy for the predicament of Irish tenant farmers than did the American journalist. Arriving on 18 February, after an unexplained side trip to Paris, he put up at the ‘spacious goodly house’ of Edenvale, the Ennis home of local landlord Richard Stacpoole. One of his first observations on walking through the town was the ubiquity of public houses. So impressed was he by the preponderance of drinking establishments that he sought some statistical backup and was told that the town (population 6,307) boasted more than 100 (legal) alehouses. This was by way of a prelude to the announcement that 23 of the 36 publicans of Milltown Malbay had been tried at Ennis assizes for boycotting the RIC. One charge was dismissed, one publican was acquitted, ten (‘the most prosperous’) signed a guarantee in court ‘not to further conspire’, while the remainder were despatched to prison to serve a month’s hard labour.

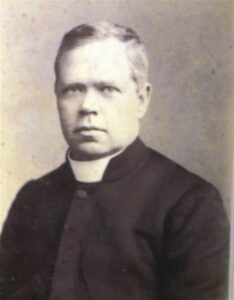

The case allowed Hurlbert to introduce another of the leading protagonists of his narrative, Father Patrick White, parish priest of Milltown Malbay, who, we are told, admitted in open court to being ‘the moving spirit of all this local boycott’. White had persuaded the other merchants of Milltown Malbay to close their premises—to make the village ‘as a city of the dead’—while the case was being conducted in Ennis. After the eleven non-penitent publicans were conducted to jail, White had gone to the home of each to offer support to their families. Mistakenly, however, he had entered the house of one of the ten signatories of the guarantee to be of good behaviour. When he realised his error, according to Hurlbert, he had quickly emerged from the traitorous premises ‘using rather unclerical language’. Hurlbert then tut-tutted that, although this was a ‘tempest in a tea-pot … it is a serious matter to see a priest of the Church assisting laymen to put their fellow men under a social interdict’.

When Hurlbert asked an RIC sergeant about the likely fate of the recanting publicans he got an interesting primer in rural economics. He was told that, although there had been suggestions that the erstwhile boycotting bar-owners would, in their turn, be ostracised by the local ‘butchers and bakers … it’s all nonsense, they are the snuggest publicans in this part of the country, and nobody will want to vex them … the best friend they have is that they can afford to give credit to the country people’.

By way of illustration of his perennial argument that many Plan tenants desperately wanted to come to terms with their landlords, Hurlbert repeated an anecdote that he had picked up from Stacpoole about a ‘good’ tenant who came to the landlord to tell him that he dare not pay his rent. When Stacpoole challenged the man, accusing him of rank cowardice: ‘The man turned rather red, went and looked out of all the windows, one after another, lifted up the heavy cloth of the large table in the room and peeped under it nervously, and finally walked up to Mr. Stacpoole and paid the money’.

In the second volume of Ireland Under Coercion Hurlbert includes Father White among ‘a certain class of the Irish clergy [associated] with the most violent henchmen of the League’ and also implies that such clerics ‘regard the assassination of “bailiffs and tax-collectors” as a pardonable, if not positively amusing, excess of patriotic zeal’.[14]

White considered suing Hurlbert for defamation, but was advised against it and contented himself with writing a pamphlet entitled Hurlbert Unmasked: an exposure of the thumping English lies of William Henry Hurlbert in his ‘Ireland Under Coercion’, in which White accused Hurlbert of having ‘libelled me unsparingly’. In addition to accusing Hurlbert of ‘cowardly and contemptible’ tactics in his ‘stream of contempt and scorn … which must have been pleasant reading, indeed, for all unionists’, White offered his justification for a Christian minister supporting the palpably un-Christian act of boycotting. Validation of his approval of the practice is summed up in his observation that ‘Desperate diseases require desperate remedies’.[15] White also retaliated by drawing attention to the number of ‘anonymous informants’ in Hurlbert’s work. These included such political insiders as a jarvey with a ‘knowing look’, a ‘sarcastic nationalist’ and a ‘shrewd Galway man’. The priest questioned their credentials and, by implication, their very existence.[16] Hurlbert, however, had anticipated some level of scepticism when it came to his protection of confidential sources and used the guarding of their identities as ammunition. He had been urgently requested, he footnoted, by an anonymous ‘friend’, who had introduced him to a number of farm labourers, to expunge their names from the manuscript of the book. This had been done at great inconvenience after the relevant chapter had gone to press. Hurlbert observed of this request: ‘What can be said for the freedom of a country in which a man of character and position honestly believes it to be “dangerous” for poor men to say the things recorded in the text of this chapter about their own feelings, wishes, opinions, and interests?’[17]

There is a bitter irony associated with Hurlbert’s later life. Having, or so it would appear, come to Ireland on a mission to discredit the supporters of Charles Stewart Parnell, he was to suffer a similar fate to that of the Irish parliamentarian. His involvement in a scandalous court case in 1891, in which evidence of an adulterous affair was introduced, left his reputation in tatters. He died, at the age of sixty-eight, in exile in Italy, far from the city of New York where, until relinquishing the editor’s spike on the World newspaper, he had been a major force.

His partisan desire to see Irish landlordism endure was not, even in the medium term, to be granted. Within fifteen years of the publication of Ireland Under Coercion, even the Tories made it clear—with the land purchase legislation introduced by chief secretary George Wyndham in 1903—that they no longer saw any agreeable future in the tea leaves for the Irish landed class.

Was Ireland Under Coercion the legacy of a journalistic spent force seeking redemption and relevance, or the observations of a cold-eyed truth-teller made without fear or favour? That verdict really depended on which side of the nationalist/unionist or tenant/landlord divide you happened to find yourself when the two-volume memoir was published in 1888.

[1] Michael Davitt, The Times Parnell Commission speech delivered by Michael Davitt in defence of the Land League (London, 1890), 152.

[2] William Henry Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion: The Diary of an American (London, 1888) Vol. 1, xxxvi.

[3] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol. 1, lvii.

[4] United Ireland, 22 August, 1888.

[5] The Times, 18 August, 1888.

[6] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol. 1, 15.

[7] James McFadden The Present and the Past of the Agrarian Struggle in Gweedore (Derry, 1889), 18.

[8] McFadden, Agrarian Struggle in Gweedore, 85.

[9] Derry Journal, 14 September 1887.

[10] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol. 1, 91-103.

[11] L.Perry Curtis Jr., ‘Three Oxford Liberals and the Plan of Campaign in Donegal, 1889’, History Ireland, May/June 2011, Volume 19.

[12] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol. 1, 117.

[13] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, vol 2, 5, 12, 248.

[14] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, Vol.2, 86.

[15] Patrick White, Hurlbert Unmasked: an exposure of the thumping English lies of William Henry Hurlbert in his ‘Ireland Under Coercion’ (New York, 1890), 18.

[16] White, Hurlbert Unmasked, 24-28.

[17] Hurlbert, Ireland Under Coercion, Vol.ii, 249.