Vidal’s “1876”

Gore Vidal’s cynical and ultimately unappealing Gilded Age novel.

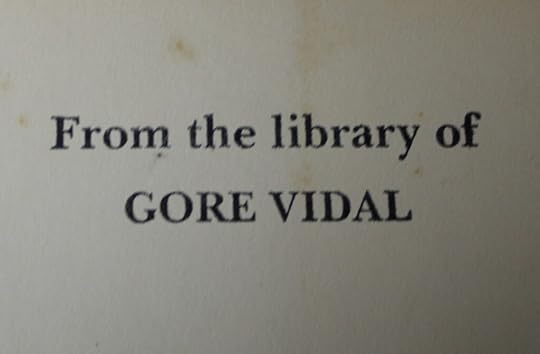

Before beginning work on my upcoming book on James G. Blaine and Roscoe Conkling, I bought a used copy of David Jordan’s authoritative biography of the New York Republican that featured an eye-catching stamp on an inside page: “From the library of GORE VIDAL.”

I knew then that at some point I would have to plunge into Vidal’s 1876: A Novel, which races through the momentous events of that year — the centennial exhibition in Philadelphia, the Republican convention in Cincinnati, and the contested outcome of the presidential election pitting Republican Rutherford B. Hayes against Democrat Samuel Tilden.

Conkling and Blaine are among the more prominent characters in 1876, which also introduces the reader to James Gordon Bennett Jr., William Cullen Bryant, Abram Hewitt, and James A. Garfield. The protagonist is Charles Schermerhorn “Charlie” Schuyler, a writer and illegitimate son of Aaron Burr returning to the United States after decades in France. Schuyler arrives in New York with his daughter, the beautiful widowed Princess Emma d’Agrigente. Financially strapped, Schuyler — like many Americans during those years — immediately launches his chase after the Almighty Dollar.

He is soon sucked into the social whirl of New York City and the political milieu of Washington D.C. Along the way he meets Mary Astor, Bennett, Blaine, Conkling, Tilden, Mark Twain, and Cornelius Vanderbilt, among others. He has a pointed exchange with President Ulysses S. Grant about the propriety of Grant’s plan to annex Santo Domingo. He promotes Tilden’s candidacy in the hope of winning a diplomatic appointment to France and replenishing his fortune.

Vidal’s portrayals of Blaine and Conkling are among the best features of his book. Although he overstates Conkling’s prospects of winning the Republican nomination for president in 1876, he succeeds in capturing Lord Roscoe’s hauteur and boldness. Blaine comes across as captivating and glib. His charisma sweeps up Princess Emma, who briefly gets caught up in Blaine’s bid for the Republican presidential nomination.

One prominent figure from the period is absent from Vidal’s pages. Frederick Douglass is nowhere to be seen. The omission is telling. Schuyler and his daughter regard Washington’s large Black population with a fascination colored by racism. Emma dubs the capital “Africa” — a nickname her father adopts — and thrills at the thought that its Byzantine politics and corruption somehow reflect the influences of that continent.

In truth, neither Schuyler nor his daughter are very likable characters. Charlie is an insufferable snob. He is a devoted — and ultimately, disillusioned — father, but he regards almost everyone else with barely concealed contempt. Emma, a widowed royal, seems keen to recover her privileged social standing and willing to consider any method available to do it.

Vidal gives us a world in which everyone is on the make and willing to countenance just about anything as they chase fortune and fame. Those qualities helped define the decades after the Civil War, but they are hardly unique to the period. Vidal’s harsh, cynical account of the Gilded Age is a caricature unredeemed by sympathy or grace.

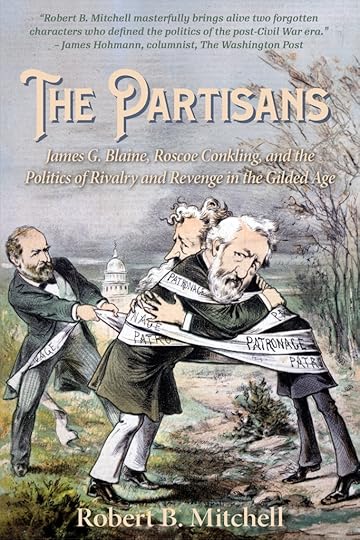

Coming soon from Edinborough Press: The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age.