Blaine goes on the attack

James G. Blaine earned bipartisan respect during his tenure as House Speaker. His partisan instincts came to the fore when he stepped down from the Speaker’s chair.

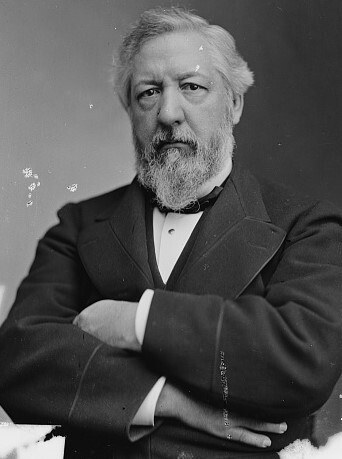

James G. Blaine in 1870. Brady-Handy Collection, Library of Congress.

James G. Blaine in 1870. Brady-Handy Collection, Library of Congress.First of two parts

On March 3, 1875, at the end of the Forty-Third Congress, James G. Blaine delivered a statesman-like valedictory to mark the conclusion of his six years as House Speaker.

“The Speakership of the American House of Representatives is a post of honor, of dignity, of power, of responsibility,” he told the House. “Its duties are at once complex and continuous: they are both onerous and delicate: they are performed in the broad light of day, under the eye of the whole people, subject at all times to the closest observation, and always attended with the sharpest criticism.” The responsibility of ruling on complex parliamentary questions meant that some of his colleagues would inevitably be disappointed or angry, he conceded. “[B]ut I am sure that no man of any party who is worthy to fill this chair will ever see a dividing line between duty and policy.”1

“Earnest and prolonged applause” erupted after his remarks.2 During his six years in the Speaker’s chair he kept fractious House Republicans more or less united and conducted himself in a way that earned the respect of Democrats, who were poised to take control of the House in the forthcoming 44th Congress. They were grateful to Blaine for preventing passage of civil rights legislation at the tail end of the 43rd Congress, but Democratic respect for the Maine Republican preceded his final hours in the chair. Two years earlier, in 1873, the House unanimously passed a resolution introduced by Representative Daniel Vorhees, D-Ind., thanking Blaine for “the distinguished ability and impartiality with which he has discharged the duties of Speaker.”3

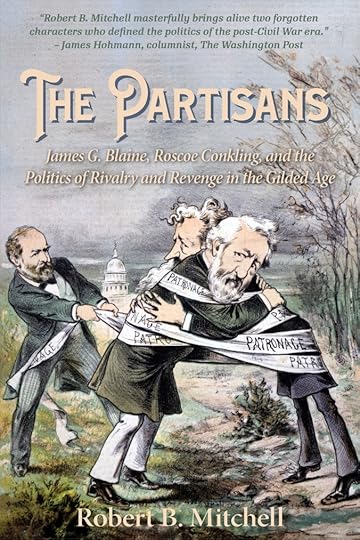

Blaine’s Andersonville speech is covered in The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age, coming soon from Edinborough Press.

Blaine’s Andersonville speech is covered in The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age, coming soon from Edinborough Press.As he basked in his colleagues’ praise on that March day, Blaine must have understood that the outpouring of good feeling was temporary at best. While many Republicans in and out of Washington loved him, others viewed him with suspicion. The respect of Democrats for the outgoing Speaker was coupled with an awareness of his acute political instincts and skills as a parliamentarian.

In the next Congress, Blaine would be leading House Republicans, who found themselves in the minority for the first time since before the Civil War. A presidential election loomed in the centennial year of 1876. Blaine was already considered a leading candidate for the Republican nomination. New conditions and opportunities required a change in behavior. Seizing the moment, Blaine mounted a full-scale attack on Democrats, who responded in kind and very nearly derailed his political career.

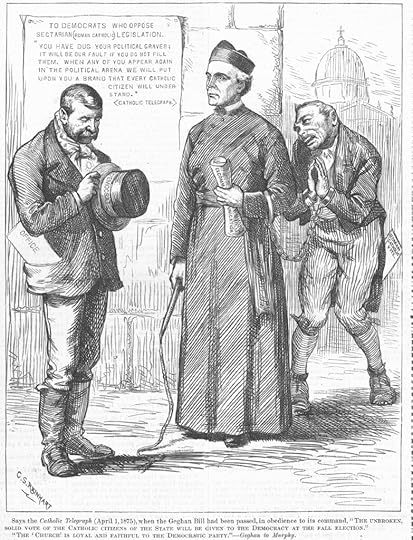

Harper’s Weekly, May 1, 1875. Republicans charged that Democrats were in thrall to militant Catholic priests seeking to undermine public school education.

Harper’s Weekly, May 1, 1875. Republicans charged that Democrats were in thrall to militant Catholic priests seeking to undermine public school education. Blaine played to the Republican base in December 1875, when he proposed a constitutional amendment to bar the use of taxpayer funds to support “sectarian” education. Sectarian was the code word used by nativists who charged that the Democratic Party aided alleged Catholic plans to subvert the non-denominational Protestant curriculum used in public schools. Ohio Republican Rutherford B. Hayes rode the school issue to victory in the race for governor and advised Blaine of its power.4

The amendment died in the Senate but enjoyed a second life as a part of Republican presidential platforms in 1876 and 1880, and it was widely adopted in the constitutions of newly admitted western states. Blaine touched a chord among Republicans but was uncharacteristically reticent about it. He made no public comment about the proposal and played no role in subsequent congressional debates.5 The son of a devoutly Catholic mother, he did not share the nativist bigotry that fueled fears of a papal plot to subvert public education. But he was willing, however halfheartedly, to pander to it.

Blaine showed no such hesitancy when Representative Samuel J. Randall, leader of the Democratic majority in the House, proposed a sweeping amnesty bill that would pardon former Confederates involved in rebellion against the United States. Blaine proposed amending the plan by excluding former Confederate president Jefferson Davis from its provisions and then outfoxed Randall by attaching his amendment to the bill.

Blaine defended his plan with a masterpiece of bloody shirt rhetoric. He charged that Davis knew of — and condoned — the appalling conditions at the Confederate prisoner-of-war camp in Andersonville, Ga. “I hear it said, ‘We will lift Mr. Davis again into great consequence by refusing amnesty,” Blaine told the House. “That is not for me to consider; I only see before me, when his name is presented, man who, by the wink of his eye, by a wave of his hand, by a nod of his head, could have stopped the atrocity at Andersonville.”

Blaine concluded with a rousing denunciation designed to elicit cheers in every Grand Army of the Republic hall throughout the North:

“Some of us had kinsmen there, most of us had friends there, all of us had countrymen there, and in the name of those kinsmen, friends and countrymen, I protest, and shall with my vote protest, against their calling back and crowning with the honors of full American citizenship the man who organized that murder.“6

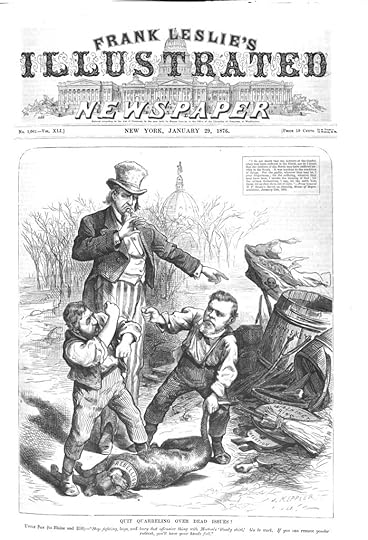

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper shows James G. Blaine (left) duking it out with ex-Confederate Ben Hill, D-Ga., while a dismayed Uncle Sam looks on.

Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper shows James G. Blaine (left) duking it out with ex-Confederate Ben Hill, D-Ga., while a dismayed Uncle Sam looks on.

Democrats were aghast. Blaine’s “amendment, couched in the spirit of partial amnesty, is designed to re-inspire wrath and capture the ear of his willing partisans,” thundered Democratic Representative Samuel “Sunset” Cox of New York. Cox was right about that; Republicans cheered. Blaine’s speech “was remarkable for its fire and force, and was the sensation of the day,” the Republican Chicago Tribune editorialized on January 11.7

But the Tribune noted something else. The next day, elaborating on the impact of Blaine’s speech, Joseph Medill’s newspaper said that Randall bill would restore Davis’s political rights and make it theoretically possible for him to run for president. “[I]n resisting such a bill for such a direct purpose, Mr. Blaine but represents the public sentiment of the great body of the American people.”8 With Blaine’s amendment attached to the amnesty bill, the measure failed to get the two-thirds majority needed for passage and died.

Blaine chose his moment carefully. Across the North there was rising concern about the prominence of former Confederates in the halls of Congress. When House Republicans sought to give Union veterans preference in hiring for congressional jobs, Democrats responded by passing a resolution declining to do so and declaring “[t]hat inasmuch as the Union of the States has been restored, all the citizens thereof are entitled to consideration in all appointments to offices under this government.” The Tribune howled that “the only test for office-holding in the House is a proof that the candidate was either an active participant in the war to break up the Union or a sympathizer with secession.” There were fears that Congress would pay rebel pensions and war debts and might even compensate former enslavers for the end of slavery.9

No doubt many of these anxieties were exaggerated. Nevertheless, they reflected the deep misgivings many in the North felt about the high congressional profile of former Confederates. And they helped Blaine move to the forefront of candidates for the Republican presidential nomination.

In the weeks that followed Blaine’s amnesty speech, Republicans began to select delegates for the Republican convention scheduled for June in Cincinnati. Blaine was the overwhelming preference of Wisconsin Republicans. In Illinois, delegates from the rural regions of the state flocked to Blaine’s banner on the strength of his speech, as did Minnesota Republicans.

“Mr. Blaine did right in this,” the St. Cloud Journal editorialized. “He is to be honored because he dares to do right, without always being too solicitous as to whether the result will be favorable or unfavorable to his personal advancement. He has long been before the public and in its service. He has an enviable record. He is known and can be trusted.”10

As winter gave way to spring, many Republicans agreed. Democrats needed to find a way to stop him before he claimed his party’s presidential nomination and rode the momentum to the White House. Unfortunately for Blaine, there was plenty of material for them to work with.

The eventful months of early 1876 are recounted in detail in The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age. Coming soon from Edinborough Press.

U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 43rd Congress, 2nd Session, March 3, 1875, p. 2,276. ︎Ibid.

︎Ibid.  ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, 42nd Congress, 3rd Session, March 3, 1873, p. 2,115.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Globe, 42nd Congress, 3rd Session, March 3, 1873, p. 2,115.  ︎Ibid., Congressional Record, 44th Congress, 1st Session, Dec. 14, 1875, p. 205; Rutherford B. Hayes to Blaine, June 16, 1875, in Gail Hamilton, Biography of James G. Blaine (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Company, 1895), p. 373.

︎Ibid., Congressional Record, 44th Congress, 1st Session, Dec. 14, 1875, p. 205; Rutherford B. Hayes to Blaine, June 16, 1875, in Gail Hamilton, Biography of James G. Blaine (Norwich, Conn., The Henry Bill Publishing Company, 1895), p. 373.  ︎Republican presidential platforms, 1876 and 1880 at The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ ;

︎Republican presidential platforms, 1876 and 1880 at The American Presidency Project https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ ;  ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 44th Congress, 1st Session, Jan. 10, 1876, pp. 325-326.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 44th Congress, 1st Session, Jan. 10, 1876, pp. 325-326.  ︎Ibid., p. 326; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 11, 1876, p.4.

︎Ibid., p. 326; Chicago Tribune, Jan. 11, 1876, p.4.  ︎Ibid., Jan. 12, 1876, p. 4.

︎Ibid., Jan. 12, 1876, p. 4.  ︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 44th Congress, 1st Session, Dec. 14, 1875, p. 208; Chicago Tribune, Dec. 17, 1875, p. 4; Weekly Kansas Chief, Troy, Kansas, Dec. 30, 1875, p. 2.

︎U.S. Congress, House, Congressional Record, 44th Congress, 1st Session, Dec. 14, 1875, p. 208; Chicago Tribune, Dec. 17, 1875, p. 4; Weekly Kansas Chief, Troy, Kansas, Dec. 30, 1875, p. 2.  ︎St. Cloud Journal, St. Cloud, Minnesota, Feb. 10, 1876, p. 2.

︎St. Cloud Journal, St. Cloud, Minnesota, Feb. 10, 1876, p. 2.  ︎

︎