Playing the Ghost

Imagine walking alone late at night along a lonesome dark avenue with a church yard full of teetering gravestones on one side of you and the jagged remains of a crumbling church on the other. Ahead of you in the gloom, you see a white figure glowing eerily, cavorting and striking dramatic poses while emitting melancholy groans.

He seems to be draped in a white sheet and covered in luminous paint. He’s sporting devil horns and wearing an animal mask. Perhaps it’s someone having a drunken lark, you think. But could it be a maniac who means you harm – why else would he be lurking among the tombs in the dead of night? Or, quite possibly, the dark gloomy atmosphere and your jangling nerves convince you that it’s a spirit from beyond the grave…

What would you do? It would take courage to continue on your way, ignoring the prancing, moaning figure in white. Would you turn and run? Would you assume it’s a prankster and attempt to pull off his ghostly disguise and deliver a punch to the miscreant’s nose?

This is a dilemma faced by countless individuals throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century when such ghost hoaxes were ubiquitous. The practice of ‘playing the ghost’ as the press called it was so common that almost every town in the country suffered from it regularly. These hoaxes are a strange but largely forgotten slice of weird history, and one that’s fascinated me for a long time.

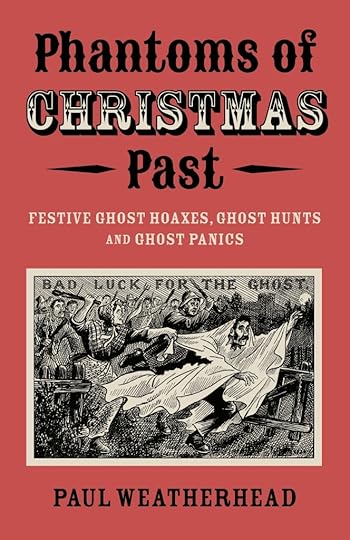

Perhaps because of the lengthening nights, these hoaxes would often begin around Halloween, escalate over November before peaking around Christmas and New Year. We love ghost stories at Christmas, so this was the ideal time for newspapers to pick up on the ghost rumours, but also to exaggerate and sensationalise them. It’s these bizarre and darkly comic festive ghost hunts, ghost hoaxes and ghost panics that I’ve unearthed for my book Phantoms of Christmas Past.

Playing the Ghost

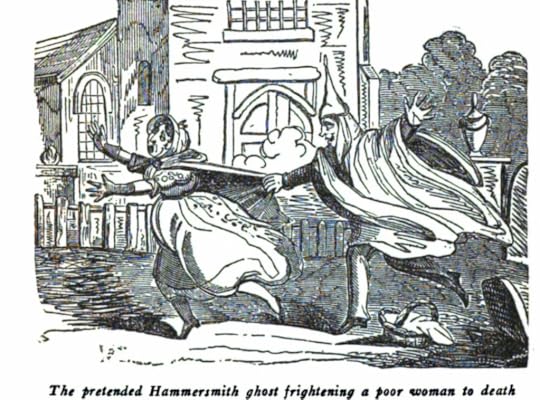

A classic example of one of these hoaxes is the story of the Hammersmith Ghost. Towards the end of 1803 a prankster had been scaring the citizens of West London by jumping out on them at night wearing a white sheet or an animal skin. Some of the ghost’s victims were so shocked that they were driven mad and never recovered, or so the press informed us.

As news of the ‘ghost’ spread, many were afraid to venture out at night and extra patrols of watchmen and vigilantes were organised. Other pranksters were inspired by what they read in the papers and carried out copycat hoaxes. On Christmas Day 1803, a coachman driving past a Hammersmith field saw a ghostly figure in white that was covered from head to foot in pigs’ bladders filled with dried peas – a common but grisly children’s toy at the time. The bladders rattled eerily as the ghost pranced and struck melodramatic poses, causing the coachman to flee in terror. Other accounts talked of the ghost breathing fire or vanishing into the ground.

As Christmas gave way to New Year, a febrile hysterical panic gripped Hammersmith, and that’s when events turned tragic.

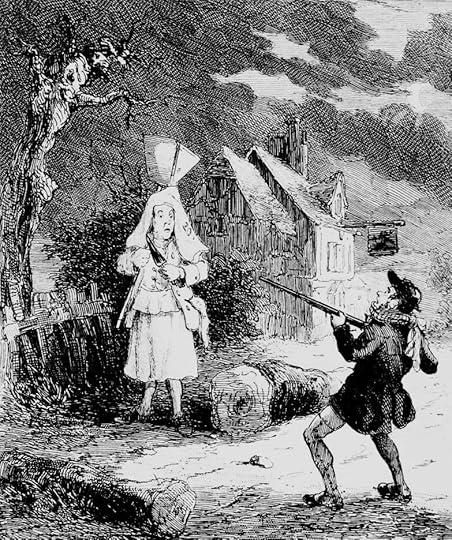

After a night of drinking, excise man Francis Smith decided to confront the ghost on 3 January 1804. Waiting on the dark winter streets, Smith eventually came across a white clad figure and asked it to identify itself. When no reply came, Smith pulled out a fowling gun and fired. He had killed innocent bricklayer Thomas Milward, who was wearing the white clothing that was typical of his profession.

Francis Smith confronts the ‘ghost’

Francis Smith confronts the ‘ghost’Francis Smith was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death, though was soon after pardoned. The Hammersmith ghost pranks were later blamed on shoemaker John Graham who admitted to dressing in a scary white costume to exact revenge on his apprentice for terrifying his children with spooky stories. Graham was certainly not the only ghost hoaxer at work in Hammersmith, but he was a convenient scapegoat which allowed the panic to dissipate.

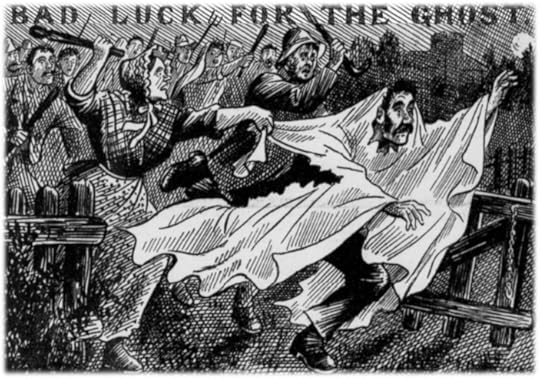

Ghost Panics: Playing the Ghost goes Viral

The story of the Hammersmith Ghost demonstrates how these ghost hoaxes could escalate into full-blown panics where people were afraid to walk the streets at night and well-meaning but not particularly sober vigilante groups were often formed. In some cases, such as when the Hammersmith Ghost made a comeback around Christmas 1824, burley young men walked the night streets dressed as women to try and honeytrap the ghost into attacking them. These cross-dressing ghost hunts were fairly common in the nineteenth century when ghost pranksters were at work, and were probably more of a drunken lark than a serious attempt to catch the ghost. However, if a ghost was caught, he would likely be badly beaten and perhaps dumped in a nearby river, canal or sewer. There was a great deal of anger directed against these hoaxers and the Hammersmith Ghost panic shows how things could easily turn ugly if you were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Ghost Busters

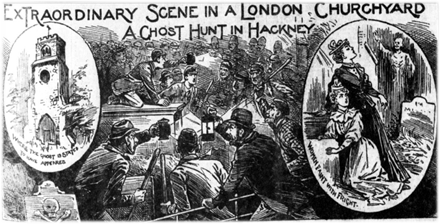

On many occasions, the vigilantes would be joined by hundreds of enthusiastic ghost hunters who’d heard rumours or read press reports about the ghost and wanted to be part of the fun. This sometimes created the conditions for what I’ve called the ghost hunting flashmob – spontaneous gatherings of enthusiastic, mischievous, and probably inebriated amateur psychic investigators.

This is what happened in Islington in 1899. A letter by someone calling himself James Chant was printed in the Islington Gazette and claimed that a ghost had been seen on Christmas Day haunting the graveyard of Saint Mary’s church. Soon, hundreds of people congregated in the churchyard and had a riotous time making uncanny noises, screaming, chasing one another among the tombs and pretending to be ghosts. The press called it ‘a vulgar riot’ and noted that many of the ghost hunting revellers returned home with their watch or wallet missing. The press speculated that the rumour had been started deliberately by thieves who would find it very easy to pick the pockets of the drunk and jostling crowds that would inevitably rush to the site of the supposed haunting.

Hackney Churchyard ghost hunt 1895

Hackney Churchyard ghost hunt 1895A beautiful example of Christmas ghost flashmobs involves the splendidly monikered Clanking Ghost of East Barnet. When accounts of this skeletal figure in his long cloak appeared in the press in the Christmas of 1926, it sparked not only a discussion in the local council over whether watchmen guarding haunted locations should be paid extra, it also led to thousands of ghost hunters descending on East Barnet every Christmas well into the 1940s. The ghost was said to be that of Sir Geoffery de Mandeville, a rebel baron who died in 1144, and it was the metallic rattling of his armour that gave him his nickname of the Clanking Ghost of East Barnet.

The Clanking Ghost of East Barnet

The Clanking Ghost of East BarnetSerious psychic investigators and spiritualists descended on the town every year hoping to make contact with Sir Geoffrey, but hordes of rowdy ghost hunters full of the Christmas spirit blocked the roads and foiled their attempts.

These Christmas ghost hunts, hoaxes and panics combine local folklore, trickery, comedy and tragedy. They still have something to teach us about how the media uncritically spread gossip and rumours and how easily populations can be swept up in panics. But these little-known episodes also reflect our love for scary stories, our penchant for mischief and riotous festive merriment.

Out now!

Out now!