Speculation on How and Where Dr. Watson Published His Holmes Chronicles, Part Two

Having now read The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1893-94), The Hound of the Baskervilles (1901-02), and The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1903-04), I have little to report regarding my quest to find out how and where Dr. Watson (as opposed to Arthur Conan Doyle) might have published his narratives about the great detective. If anything, that rascally Conan Doyle seems to have inched away from providing me any clues. Let’s take a glance at what little there is, and then I’ll toss around an idea or two regarding the author’s attempt to kill off his most famous creation.

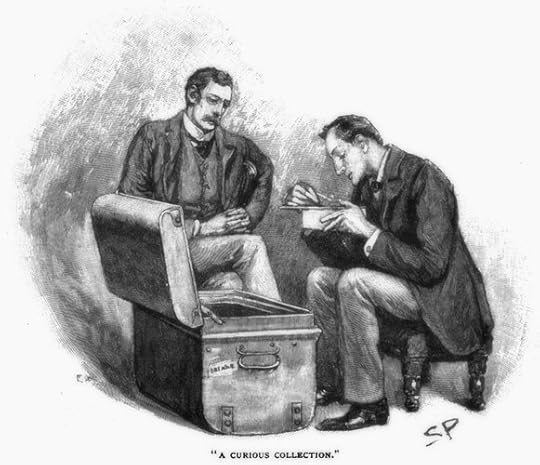

Sidney Paget’s illustration of Watson and Holmes for “The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual,” published in The Strand Magazine and later collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

Sidney Paget’s illustration of Watson and Holmes for “The Adventure of the Musgrave Ritual,” published in The Strand Magazine and later collected in The Memoirs of Sherlock HolmesThe Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes

“Silver Blaze”

Holmes: “…I made a blunder, my dear Watson — which is, I am afraid, a more common occurrence than anyone would think who knew me through your memoirs.”

“The Yellow Face”

Watson: “In publishing these short sketches based upon the numerous cases in which my companion’s singular gifts have made us the listeners to, and eventually the actors in, some strange drama, it is only natural that I should dwell rather upon his successes than upon his failures.”

“The Gloria Scott”

Holmes [after recounting an investigation he handled before meeting Watson]: Those are the facts of the case, doctor, and if they are of any use to your collection, I am sure that they are very heartily at your service.”

“The Musgrave Ritual”

Watson [regarding Holmes’ occasional “outbursts of passionate energy”]: “…as I have mentioned somewhere in these incoherent memoirs…”

Holmes [regarding his early cases]: “Yes, my boy, these are all done prematurely before my biographer had come to glorify me.”

Holmes [to Watson]: “But I should be glad that you should add this case to your annals….”

“The Reigate Squires”

Watson [regarding a case “too recent in the minds of the public” and too heavy in politics and finances]: “…to be fitting subjects for this series of sketches.”

“The Crooked Man”

Holmes: “…the effect of some of these little sketches of yours…”

“The Resident Patient”

Watson: “Glancing over the somewhat incoherent series of Memoirs with which I have endeavoured to illustrate a few of the mental peculiarities of my friend Mr Sherlock Holmes, I have been struck by the difficulty which I have experienced in picking out examples which shall in every way answer my purpose… [Some illustrate Holmes’s brilliant reasoning but the facts of the case are so dull] that I could not feel justified in laying them before the public…. [That brilliance isn’t highlighted in this case, but] the whole train of circumstances is so remarkable that I cannot bring myself to omit it entirely from this series.”

“The Greek Interpreter”

Mycroft Holmes [to Watson]: “I hear of Sherlock everywhere since you became his chronicler.”

“The Naval Treaty”

Watson [after mentioning three cases “recorded in my notes”]: “The first of these, however, deals with interests of such importance and implicates so many of the first families in the kingdom that for many years it will be impossible to make it public…. The new century will have come, however, before the story can be safely told.” [Instead, he narrates the second investigation.]

“The Final Problem”

Watson: “It is with a heavy heart that I take up my pen to write these the last words in which I shall ever record the singular gifts by which my friend Mr Sherlock Holmes was distinguished.” [Holmes, you see, dies at the end of this case. Luckily, his condition improves afterward.]

The Hound of the Baskervilles

By the fireside on a “raw and foggy night” in late November, Holmes recounts the terrible tale of a gigantic — and possibly spectral — pooch.

By the fireside on a “raw and foggy night” in late November, Holmes recounts the terrible tale of a gigantic — and possibly spectral — pooch.Watson: “…I had often been piqued by his indifference to my admiration and to the attempts which I had made to give publicity to his methods.”

Stapleton [to Watson]: “The records of your detective have reached us here [in rural Devon], and you could not celebrate him without being known yourself.”

Watson: “So I have been able to quote from the reports which I have forwarded during these early days to Sherlock Holmes. Now, however, I have arrived at a point in my narrative where I am compelled to abandon this method and to trust once more to my recollections, aided by the diary which I kept at the time.

The Return of Sherlock Holmes

“The Norwood Builder”

Watson: “[Holmes] bound me in the most stringent terms to say no further word of himself, his methods, or his successes — a prohibition which, as I have explained, has only now been removed.”

Holmes: “Perhaps I shall get the credit also at some distant day when I permit my zealous historian to lay out his foolscap one more — eh, Watson?”

“The Solitary Cyclist”

Watson: “As I have preserved very full notes of all these cases, and was myself personally engaged in many of them, it may be imagined that it is no easy task to know which I should select to lay before the public…. I will now lay before my reader the facts connected with Miss Violet Smith…. [T]here were some points about the case which made it stand out in those long records of crime from which I gather the material for these little narratives.”

Watson: “In the whirl of our incessant activity it has often been difficult for me, as the reader has probably observed, to round off my narratives, and to give those final details which the curious might expect…. I find, however, a short note at the end of my manuscripts dealing with this case, in which I have put it upon record that Miss Violet Smith did indeed inherit a large fortune….”

“The Six Napoleons”

Holmes: “If ever I permit you to chronicle any more of my little problems, Watson, I foresee that you will enliven your pages by an account of the singular adventure of the Napoleonic busts.”

“The Three Students”

Watson: “It will be obvious that any details which would help the reader to exactly identify the college or the criminal would be injudicious and offensive. So painful a scandal may well be allowed to die out.”

“The Missing Three-Quarter”

Watson: “Young Overton’s face assumed the bothered look of the man who is more accustomed to using his muscles than his wits; but by degrees, which may repetitions and obscurities which I may omit from his narrative, he laid his strange story before us.” [Watson then provides an edited transcription of what Overton narrated.]

“The Abbey Grange”

Holmes: “…I must admit, Watson, that you have some power of selection which atones for much which I deplore in your narratives. Your fatal habit of looking at everything from the point of view of a story instead of as a scientific exercise has ruined what might have been an instructive and even classical series of demonstrations. You slur over work of the utmost finesse and delicacy in order to dwell upon sensational details which may excite, but cannot possibly instruct, the reader.”

“The Second Stain”

Watson: “I had intended ‘The Adventure of the Abbey Grange’ to be the last of those exploits of my friend, Mr Sherlock Holmes, which I should ever communicate to the public. This resolution of mine was not due to any lack of material, since I have notes of many hundreds to cases to which I have never alluded, nor was it caused by any waning interest on the part of my readers in the singular personality and unique methods of this remarkable man. [The reason is positive publicity helped Holmes while he was active, but now that he’s retired,] notoriety has become hateful to him…. [Holmes allows Watson to publish this narrative to fulfill a promise and to illustrate] the most important international case which he has ever been called upon to handle. [However, it is] a carefully-guarded account of the incident…. If in telling the story I seem to be somewhat vague in certain details the public will readily understand that there an excellent reason for my reticence.

“The Abbey Grange” repeats one of Holmes’ complaints about Watson’s chronicles that he’d been making from the start: his biographer prefers to tell a ripping yarn rather than elucidate a lesson in crime-solving. However, when Holmes jumps out and says “Boo! I survived Reichenbach!” at the start of The Return, Watson grows more than hitherto concerned with 1) drawing from his extensive records and 2) protecting the identities of persons or institutions involved therein. None of this, however, offers us a clue of where Watson sent his manuscripts for publication.

I’m hesitant to point to The Strand Magazine as the journal in which the Holmesverse public read Watson’s chronicles. As mentioned last time, The Strand is not mentioned at all in the canon, and why Conan Doyle’s name is on them in that publication is befuddling. In Hound, Watson cites the Devon Country Chronicle, which seems to exist solely in the Holmesverse, not in, well, wherever it is The Strand exists. The Doyleverse? The Ourverse? Therefore, I have a hunch Watson published in a journal that isn’t available to you or me. We do know from “The Second Stain” that it was a journal with a solid readership, since the great detective’s popularity was unfailing. This is about as good a clue as Conan Doyle gives: Watson got his stuff published in such a way that it became and remained well-known.

A Few Thoughts on Holmes ResurrectedI suspect a lot of my readers already know that Conan Doyle pushed — well, nudged — Holmes and Moriarty off Reichenbach Falls in “The Final Problem,” the last story in Memoirs. He subsequently wrote Hound, but he set it prior to that fateful plunge. I’ve read biographers say Conan Doyle had grown sick and tired of Holmes, and he did the terrible deed to be free to focus on other writing.

And yet, an anecdote Conan Doyle share in the 1920s suggests he retained a fondness for his famous detective — or, at least, recognized that the tales were worth retelling. By this decade, Conan Doyle had reinvented himself as a global advocate of Spiritualism, and in Our Second American Adventure (1924) he recounts spreading the word across North America. While passing through Los Angeles, the famous author met a famous child star — and later Uncle Fester — Jackie Coogan. Conan Doyle writes:

They asked me to be photographed with [Coogan], so I employed the time telling him a gruesome Sherlock Holmes tale, and the look of interest and awe upon his intent little face is an excellent example of those powers which are so natural and yet so subtle.Clearly, Conan Doyle hadn’t abandoned Holmes completely. In fact, if the situation called for it, he entertained a kid with one of the old cases.

Allow me to suggest, then, another motive for Conan Doyle sending Holmes down the waterfall when he did: the author, cranking out new cases each month, was struggling to invent suitable mysteries. Some of the tales in Memoirs feel different from those in Adventures and the first two novels, especially “The Yellow Face” and “The Gloria Scott.” While Holmes and Watson get involved in these mysteries, they look on from a bit of a distance as things resolve themselves. It’s as if Conan Doyle was squeezing his series characters into independent tales that would’ve been about as good without them.

Memoirs also reveals Conan Doyle starting to repeat himself. “The Stockbroker’s Clerk” isn’t all that different from “The Red-Headed League” in that a person is hired to perform a kooky job as a diversion for robbery. Now, I very much enjoy Hound, but it seems like an elaboration on “The Copper Beeches,” given the Gothic mansion and the ravenous dog. Part of the problem, I admit, is the fact that I’m reading these works within a span of weeks, not of months or years, as did the original readers. Still, this approach might permit glimpses into Conan Doyle’s head that wouldn’t otherwise be available.

Ah well. Slow and steady solves the mystery. More to come.

Part Three is forthcoming