Blaine, Conkling, and power

The two very different Gilded Age Republican politicians practiced their craft in distinctive ways. One showed the way to the future.

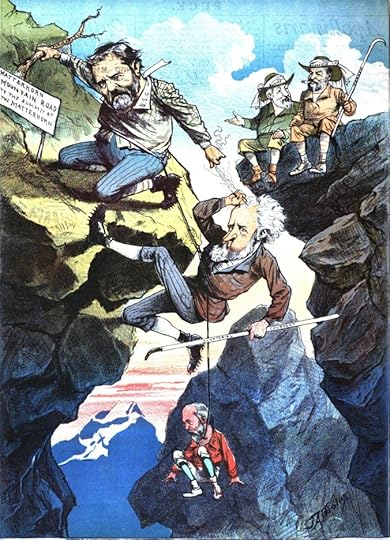

A cartoon from Puck shows Ulysses S. Grant, Roscoe Conkling, and Tom Platt dangling above an Alpine crevice as President James A. Garfield and Secretary of State James G. Blaine (upper right) contentedly look on.

A cartoon from Puck shows Ulysses S. Grant, Roscoe Conkling, and Tom Platt dangling above an Alpine crevice as President James A. Garfield and Secretary of State James G. Blaine (upper right) contentedly look on.For many reasons, the Gilded Age feud between Republicans James G. Blaine of Maine and Roscoe Conkling of New York marked a watershed chapter in American politics.

Their 18-year rivalry determined the leadership of the Republican Party as the United States recovered from the Civil War and evolved from an agrarian economy into an industrial powerhouse. They battled each other to a draw at presidential nominating conventions in 1876 and 1880 before Republicans finally turned to Blaine as their nominee in 1884. Their ferocious infighting over patronage and clout in the administration of President James A. Garfield ended when a gunman, inflamed by the feud, fatally shot the president.

But the significance of the Blaine-Conkling feud had as much to do with the manner in which they practiced their craft as the momentous confrontations that dominated their careers. From the moment in 1866 when Blaine antagonized Conkling by mocking the New Yorker’s “grandiloquent swell and “overpowering turkey-gobbler strut,” it was clear that they took vastly different approaches to the business of gaining and cultivating power and influence.

Personality in large measure shaped their different political styles. Blaine was an early and skilled practitioner of retail politics. Personable and affable, he possessed a photographic memory that enabled him to make acquaintances feel like friends by remembering personal details and circumstances. He could explode when provoked, as his exchange with Conkling demonstrated, but such outbursts were rare.

Blaine in Puck.

Blaine in Puck.During his decades-long career in politics, Blaine’s personal charisma and charm enabled him to assemble a loyal cadre of supporters across the country. One of his many admirers told Brooklyn Eagle correspondent Billy Hudson: “He is irresistible. I defy anyone, Republican or Democrat, to be in his company for half an hour and go away anything else than a personal friend.”1

Conkling, on the other hand, belonged to that curious subset of politicians who preferred not to deal with people. When backslapping and glad-handing were required, as when he mounted his first campaign for the Senate in 1867, he could force himself to be sociable. When Black Mississippi Republican Blanche Kelso Bruce was ignored on the Senate floor in 1875 as he presented his credentials, Conkling introduced himself, extended his arm, and escorted his fellow Republican to the clerk’s desk.

But such displays were rare. Truculence was Conkling’s default setting. Where Blaine built a devoted personal following with charisma and charm, Conkling kept allies at arm’s length and alienated subordinates with his imperious personality. He sparred in the boxing ring to stay in shape. He was rumored to carry a gun on the Senate floor. He delighted in skewering enemies in debate and intimidating underlings. The press dubbed him “Lord Roscoe.” “Without malignity,” journalist George Alfred Townsend wrote in 1872, “Conkling is nothing.”2

Roscoe Conkling in Puck.

Roscoe Conkling in Puck.As significant as these personal differences were, a more important factor separated Blaine and Conkling as they fought for power. For the first time, politicians could reach voters — and gain insights into public opinion — through advances in technology that made it possible for news to be disseminated more widely and more quickly than ever before.

Ahead of the invention of the telephone, and long before radio, TV, and the internet, the era of mass media began on the printed page as newspapers sprouted from New England to California. By 1870, more than 5,000 dailies and weeklies served readers in county seat towns and big cities. Small towns could support two newspapers that catered to Democrats or Republicans, while in big cities, more than 150 dailies claimed circulation in excess of 10,000. The telegraph brought news from Washington, where dozens of correspondents kept hometown readers apprised of news from Capitol Hill and the White House. Advances in printing technology enabled newspapers to print tens of thousands of copies an hour, many of which were widely distributed via the railroad.3

Blaine was uniquely equipped — by experience and facility with words — to take advantage of the rising power of the press. Before entering politics, he worked as an editor on newspapers in Augusta and Portland, Maine. Blaine “was especially fitted for the field of journalism,” biographer Theron Clark Crawford wrote. “He had a keen sense of the public’s wants, and through this sense was close in sympathy with the popular will. He had the experienced and successful editor’s ability to recognize the leading topic of the moment.”4

While it did not insulate him from negative headlines, Blaine’s relationship with the press worked to his advantage — and he knew it. “Oh, I’m one of them myself, and I like the breed of dogs,” Blaine said of the correspondents who wrote about him. “Besides, it is a better thing to have the boys who write about you dip their pens in the ink of friendship than that of gall.”5

Clark noted that, in at least one instance, Blaine’s relationship with the press went beyond friendship. Blaine wrote anonymously for the New York Tribune and was widely believed to have been the author of an editorial published by the paper in 1881 regarded as a declaration of war by the Garfield administration against Empire State Stalwarts aligned with Conkling.

While Blaine cultivated his relationship with the press, Conkling kept correspondents at arm’s length and menaced editors. When a Washington newspaper was poised to print an article about Conkling’s extramarital affairs, Conkling stormed into the office, demanded to see the article, and then threatened to kill the editor if he published the story.

Lord Roscoe cared enough about press management to share texts of his major speeches with correspondents but showed nothing of Blaine’s flair for cultivating relationships with them. As he fought to be returned to the Senate after dramatically resigning in 1881, Conkling summoned a correspondent from the New York Herald to declaim about Blaine’s malevolence and demand that the Herald print an article attacking Garfield for duplicity regarding management of the Port of New York, the patronage bastion which served as the basis of Conkling’s political strength.

The Herald obliged, but it was too late. The vast majority of New York newspapers had already gone on record supporting Garfield.6 In the years to come, the savviest politicians in both parties emulated Blaine’s approach to dealing with the press.

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age, is now available for pre-order at amazon.com.William C. Hudson, Random Recollections of an Old Political Reporter (New York: Cupples & Leon Co., 1911), p. 128. Hereafter referred to as Hudson.

The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age, is now available for pre-order at amazon.com.William C. Hudson, Random Recollections of an Old Political Reporter (New York: Cupples & Leon Co., 1911), p. 128. Hereafter referred to as Hudson.  ︎“Gath” (the pen name of George Alfred Townsend), “Washington,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 31, 1872, p. 2.

︎“Gath” (the pen name of George Alfred Townsend), “Washington,” Chicago Tribune, Dec. 31, 1872, p. 2.  ︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Press Gang: Newspapers & Politics 1865-1878 (University of North Carolina Press, 1994, pp. 10-13).

︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Press Gang: Newspapers & Politics 1865-1878 (University of North Carolina Press, 1994, pp. 10-13).  ︎Theron Clark Crawford, James G. Blaine. A Study of His Life and Career (Edgewood Publishing Co., 1893), pp. 36-37.

︎Theron Clark Crawford, James G. Blaine. A Study of His Life and Career (Edgewood Publishing Co., 1893), pp. 36-37.  ︎Hudson, p. 128.

︎Hudson, p. 128.  ︎Alan Peskin, Garfield (The Kent State University Press, 1978), pp. 569-570.

︎Alan Peskin, Garfield (The Kent State University Press, 1978), pp. 569-570.  ︎

︎