RAPTURE MYTHS vs LIVED AEONS

In my latest instalment of the New Aeon Agora YouTube series, I explored a subject that continually captures popular imagination: the Rapture. With each passing year, date-setters predict a secret evacuation of believers; yet another weekend comes and goes without a trumpet call. In the video, I sketched the history of this modern doctrine, contrasted it with the Thelemic understanding of time and spiritual evolution, and urged viewers to focus on real injustices rather than apocalyptic fantasies.

Because the response to that video has been so engaging, this article takes the conversation further. Here you’ll find additional historical detail about John Nelson Darby and the Plymouth Brethren, insight into how Aleister Crowley’s upbringing within that sect shaped his rebellion, and a deeper look at the Thelemic idea of the Succession of the Aeons.

If you haven’t watched the video yet, I encourage you to do so; it marks the beginning of a renewed commitment to my YouTube channel. For now, settle in for an exploration that weaves biography, theology, and social critique.

Magick Without Tears with Marco Visconti thrives on reader support. By choosing a paid subscription, you help keep new posts coming and fund ongoing research and writing. Thank you for considering a paid subscription to support this publication.

The Rapture is a Recent InventionMany Christians assume that the idea of a pre‑tribulation Rapture is ancient, but historical evidence shows that it emerged in the nineteenth century. Before that time, most American and European believers adhered to postmillennial or amillennial interpretations, believing the Church would persevere through tribulation to ultimately triumph.

In contrast, Dispensationalism, the system that introduced the very idea of the Rapture, divides sacred history into distinct administrations, draws a hard line between ethnic Israel and the Church, and inserts a secret removal of believers before a final period of turmoil.

This framework originated not with the early Church or the Nicene Creed, but with John Nelson Darby, a nineteenth-century Anglo-Irish cleric and a founding figure of the Plymouth Brethren. Darby’s scheme identified six “dispensations” and argued that 1 Thessalonians 4:17 pointed to a future event in which Christ would snatch believers away before resuming his dealings with Israel.

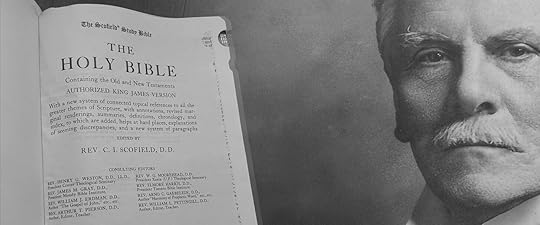

Dispensationalism’s novelty is not disputed by historians of theology. Darby formulated a new system of theology in the mid‑1800s. Its spread owed less to exegetical elegance than to persuasive marketing. American pastor Cyrus I. Scofield embedded Darby’s interpretations into the footnotes of his Scofield Study Bible, first published in 1909. This study Bible sold more than two million copies in its early years and convinced readers that its notes were the definitive exposition of the biblical text.

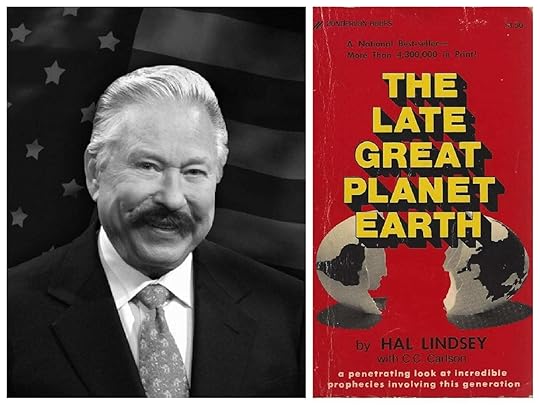

Popular authors followed. Hal Lindsey’s 1970 bestseller The Late Great Planet Earth repackaged Darby’s timetable for a Cold War audience, and the 1990s Left Behind novels by Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins turned the same outline into thriller fiction.

The result has been a generation of believers for whom a pre‑tribulation Rapture feels like mere Christianity, even though it has a very specific pedigree.

Core Claims of DispensationalismDispensational theology rests on three primary assertions:

Historical divisions: History is divided into discrete eras in which God interacts with humanity in different ways.

Israel–Church distinction: A sharp distinction is drawn between ethnic Israel and the Christian Church; promises to Israel are not applied to the Church.

Secret Rapture: Believers will be “caught up” to meet Christ, halting the “Church age” and restarting Israel’s prophetic clock.

These claims provide the logic for the chart on so many prophecy conference brochures. Without the Rapture, the dispensational timetable falls apart. What is often presented as biblical inevitability is, in fact, a modern program devised by a particular preacher within a specific movement.

John Nelson Darby and the Plymouth BrethrenFrom Barrister to Sectarian LeaderDarby was born in London in 1800, the youngest son of an Anglo‑Irish merchant family. A gifted student, he graduated first in his class from Trinity College, Dublin. Although he had trained for the legal profession, he soon abandoned it for the Anglican ministry. Yet he found himself increasingly disenchanted with the established church. After a riding accident forced a period of convalescence, he embraced radical biblicism, believing truth could be found in Scripture alone and interpreted literally. He also articulated a conviction that the church was a spiritual priesthood of believers rather than a hierarchy of clerics.

By the late 1820s, Darby began meeting with a group of like‑minded evangelical malcontents in Dublin, individuals who sought to return to New Testament simplicity by gathering without official clergy and celebrating the Lord’s Supper together. These meetings laid the foundation for the Brethren movement, which soon spread to Bristol, Plymouth, and beyond. Darby wrote in his letters that finding brethren acting together in Plymouth “altered the face of Christianity to me”. Although the Brethren resisted denominational labels and preferred to be called simply “Christians,” outsiders began to refer to them as the Plymouth Brethren.

The Brethren’s Distinctive IdeasAmong the Plymouth Brethren, a cluster of practices and convictions developed that made their communities instantly recognisable, not because they embraced novelty for its own sake but because they believed they were returning to the primitive simplicity of the apostolic church. The most visible expression of this ideal was the weekly “breaking of bread,” a communion celebrated not in consecrated chancels and certainly not under the presidency of an ordained sacerdotal class, but in parlours, rented rooms, and modest halls where any baptised believer might rise to offer a prayer, read a passage of Scripture, or speak as the Spirit prompted. The rite was less a liturgical performance than a living conversation, and the absence of clerical mediation served as a continual reminder that authority resided in the gathered body and in the immediacy of the Holy Spirit rather than in ecclesiastical office.

This ecclesiology of immediacy cohered with an ethic of separation that Darby and his adherents raised to a principled program. Convinced that doctrinal error and moral compromise were not accidental blemishes but structural features of the visible churches, they treated fellowship as something to be guarded with jealous care, refusing communion with congregations or individuals they deemed contaminated by false teaching or lax discipline. The result was a community that prized purity over breadth and that accepted social isolation as the necessary cost of fidelity.

Undergirding these choices was an eschatological outlook marked by heightened expectancy. Christ’s return was not a remote hope to be filed under long-term theological concerns; it was imminent, always on the threshold, and it cast a stark light on the present. If the Church existed in a state of ruin, as Darby insisted, then reforming the historic denominations was a distraction from the obedience of the hour. Christians ought to meet, keep themselves unspotted, and await the Lord. Efforts to reconstruct Christendom were not only futile but theologically misguided, since they risked mistaking human architecture for divine order.

Darby’s system took on its full coherence during the prophetic conferences at Powerscourt House in County Wicklow, convened under the patronage of Lady Theodosia, Countess of Powerscourt. In that charged setting, he refined the scaffolding that would become dispensationalism: the division of sacred history into discrete economies, the notion of a parenthetic “Church age” in which God’s dealings with Israel are temporarily suspended, and the pivotal claim of a Rapture that would remove believers before the final tribulation. These constructions did not remain abstract; they generated friction within the movement itself, since the logic of separation pressed some assemblies toward a rigour that others found untenable.

The Crowley ConnectionA Childhood Under the BrethrenThe ensuing rupture produced Darby’s Exclusive Brethren on one side and the more open gatherings on the other, and the culture of strict separatism that crystallised around the Exclusive party foreshadowed the intense sectarianism that would frame the early life of Aleister Crowley.

Aleister Crowley, born Edward Alexander Crowley in 1875, entered the world of the Plymouth Brethren from the moment of his baptism. His parents, Edward and Emily Crowley, were Plymouth Brethren of the strictest kind. Edward Crowley had inherited wealth from the brewery trade but devoted himself to preaching; he was revered within the sect, and his son adored him. The household adhered to Brethren principles, which included daily family worship, a literal interpretation of Scripture, and abstention from worldly entertainments. Crowley later wrote that the Bible was the only book permitted in the home and that games, music, and novels were banned. This austere environment shaped his imagination in ways he would later both rebel against and reappropriate.

This is not abstract church history for our purposes, because Aleister Crowley was born into precisely that world. His father, Edward Crowley, left engineering to preach as an Exclusive Brother, flooding the streets and the post with tracts, buttonholing strangers with the unnerving catechetical question “and then?”, and becoming a minor but tireless evangelist of Darbyite rigour. Family life followed suit: daily Bible readings, a Spartan upbringing that disdained holidays and toys, a closed circle of “walking Bibles” whose disputes were settled with “It is written” and “Thus saith the Lord.” Crowley later remembered that atmosphere with a complicated mixture of admiration for his father’s strength and revulsion for the sect’s absolutism; the memories deepen after Edward’s premature death in 1887, when a fresh Brethren schism—this time the Raven Division—pushed his mother into still more stringent devotion and tore even the family’s social fabric. The boy who would become Perdurabo learned early how quickly one could fall from “chosen” to “damned” when a new doctrinal hair was split. The intensity of his break with Protestant literalism makes far more sense once you see the walls he grew up inside.

There is another detail—almost folkloric now but rooted in that household’s habits. For much of his infancy and adolescence, the Bible was his only reading, and his mother, exasperated by his wilfulness, called him “The Beast,” a stinging label that sent him prowling through Revelation and left him electrified by the book’s lurid figures. That imaginative seed matters; Crowley’s later symbolic world did not arrive from nowhere. It grew in soil tilled by Brethren severity and apocalyptic fascination, and it flowered into a thorough revolt against fear-dressed-as-faith.

The strict Brethren environment also imposed social isolation. Crowley attended Brethren schools, where dayboys were taught to fear the world outside their sect. He internalised the language of apocalypse and judgment but chafed against the hypocrisies he perceived among believers. When he later encountered the broader world at Malvern College and Tonbridge School, he experienced bullying and sexual repression, which further soured him on conventional Christianity. This combination of religious intensity and personal disillusionment provided fertile soil for his later attraction to occultism.

Flight to Cambridge and the OccultIn 1895, Crowley finally overcame family opposition and entered Trinity College, Cambridge. There, he immersed himself in literature, poetry, chess, and mountaineering. For the first time, he indulged in pleasures previously forbidden: sex (and bisexuality), smoking, and wine. Cambridge liberated him from the suffocating moralism of the Brethren and exposed him to new philosophical ideas, including the works of Richard Burton and French decadent literature. During this period, he also began reading widely on esotericism. He wrote to occultist A. E. Waite, asking for guidance in finding the “Secret Sanctuary” described in the 18th‑century classic, The Cloud upon the Sanctuary. Waite’s suggestion to read that text accompanied Crowley on a climbing holiday, and he resolved “to find and enter into communication with this mysterious brotherhood”.

Crowley’s initiation into the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in 1898 provided the framework for his lifelong pursuit of magick. Yet the antagonistic relationship with his mother and the memory of his father’s strict Brethren preaching continued to haunt him. In his Confessions, he attributed his early turn to the occult to the shock of his father’s death and his sense that God had failed to protect them. His later disdain for Christian fundamentalism and his celebration of personal sovereignty can be read as an inversion of the Plymouth Brethren ethos. Crowley did not merely reject his upbringing; he transmuted it into the mythos of Thelema, making his childhood demons into symbols and tools.

The Thelemic Idea of the Succession of the AeonsAeons as Spiritual ParadigmsOne of Crowley’s most creative contributions to modern esotericism is the concept of Aeons. In Thelema, an Aeon is a vast epoch characterised by a particular spiritual formula. Crowley identified three major historical Aeons—Isis, Osiris, and Horus—each reflecting a distinct religious and cultural paradigm. According to Thelema, these shifts are not arbitrary but arise from the evolution of human consciousness.

Aeon of Isis: This earliest epoch was matriarchal and nature‑oriented. The Great Goddess—known as Isis to the Egyptians, Demeter to the Greeks, and Kali to the Hindus—represented fertility, motherhood, and the earth. Worship during this Aeon focused on mysticism, intuition, and the cycles of nature. We can think of it as the (perhaps mythical) “Age of the Great Goddess”, and its magical formula was based on humanity’s perception of spontaneous growth and continuous life.

Aeon of Osiris: In the classical and medieval periods, the matriarchal paradigm gave way to patriarchy. The Aeon of Osiris centred on the dying and resurrecting god, embodied by divine figures such as Osiris, Dionysus, and Christ, and emphasised sacrifice, moral dualism, and submission to a paternal deity. Religious institutions became hierarchical and dogmatic. Individuals were seen as fallen beings in need of redemption. Several Thelemic writers later elaborated that this era hid esoteric knowledge beneath layers of ritual and dogma.

Aeon of Horus: Crowley announced that a new Aeon began in 1904 when he received Liber AL vel Legis. The Aeon of Horus emphasises individual self‑realisation, sovereignty, and the pursuit of True Will. Horus, the child god, crowned and conquering, symbolises renewal and potential. In this era, spiritual authority shifts inward; each person is called to discover and fulfil their unique purpose. Crowley summarised this ethos in the famous maxim from Liber AL: “Every man and every woman is a star”.

Crowley warned against interpreting the Aeons as astrological ages or as excuses for escapism. In The Book of Thoth, he explained that the magical doctrine of the succession of the Aeons is connected with the precession of the zodiac. He associated the Aeon of Isis with Pisces and Virgo, the Aeon of Osiris with Aries and Libra, and the present Aeon of Horus with Aquarius and Leo. Yet he also noted that seers in the Osirian age feared the coming change because they misunderstood the precession of Aeons and equated every transition with catastrophe. For Thelemites, Aeonic shifts are not disasters but opportunities for conscious evolution.

Aeons versus DispensationsUnderstanding the Aeons provides a precise vantage point from which to set Thelema beside Darby’s dispensationalism. Both schemas describe history as articulated into distinct epochs, and both assign to each period a characteristic formula that shapes religion and conduct. Yet the likeness ends there, because the mechanisms that drive change are conceived in utterly different terms. Dispensationalism envisions a divine legislator issuing new administrative orders at regular intervals, so that the spiritual economy of humanity hinges on fresh decrees. The Aeonic model treats history as a drama of consciousness rather than an alternation of statutes; its turning points arrive as shifts in symbolic language, mythic pattern, and interior orientation, and what changes is not the letter of a law but the quality of awareness through which men and women apprehend themselves and the world.

These divergent premises naturally give rise to divergent postures toward human agency. In the dispensational chart, the drama reaches its fever pitch with a sudden extraction of the faithful, and agency becomes largely a matter of waiting rightly for rescue. Thelemic aeonics refuses that exit. The Aeon of Horus speaks to sovereignty and to the burdens that accompany it, asking each person to take responsibility for a life shaped in accordance with True Will and to meet the world as a field of work rather than as a catastrophe to be dodged. The energy is affirmative, not evasive; it encourages the practitioner to stand upright, to act, and to accept the consequences of their actions as part of maturation.

So too with suffering, which the popular Rapture narrative either avoids through timely evacuation or imagines as a chastisement visited upon others once the righteous have been removed from the stage. In Thelema, no timetable dissolves pain by decree. Suffering is not a clerical error in the cosmos. Still, one of the materials through which character is tempered and clarity is won, and the task is to confront and integrate it within the discovery of True Will. The passage forward is not the erasure of difficulty but its transmutation.

The ethos is set in a single sentence of Liber AL: “Every man and every woman is a star.” Each of us has a trajectory that is neither interchangeable nor negotiable, and no one is licensed to seize the helm of another’s course. In that sense, the Aeon of Horus democratises spiritual life, since the measure of authenticity is not conformity to an external program but fidelity to an interior law.

There is no cosmic escape hatch concealed behind the clouds. There is only the steady labour of becoming who you are meant to be and of ordering your orbit so that your light can be of use.

Why the Rapture Myth PersistsDarby’s timetable did not become dinner-table common sense through scholastic elegance alone, nor by the patient work of exegesis; it spread because the Scofield Reference Bible of 1909 stitched a vast apparatus of commentary directly to the sacred page, so that for millions of readers the marginal notes carried the gravitational pull of Scripture itself, and because late twentieth-century popularisers converted a technical scheme into cultural air. Hal Lindsey distilled the system into a brisk bestseller, the Left Behind franchise repackaged it as page-turning melodrama, and a once sectarian calculus migrated from prophecy conferences and Bible institutes into Sunday school charts, radio sermons, and televised pulpits, until a Victorian minority report had been naturalised as something like mere Christianity for a wide swath of American Protestants.

Its durability, despite a recent origin and a fragile scriptural foundation, rests on the incentives of an outrage economy. The narrative furnishes stock villains, confers insider status, and turns eschatology into a renewable product line; when a date fails, the goalposts slide, a fresh graphic appears, and the market obligingly resets.

By contrast, facing the prosaic emergencies that shape our lives offers no narcotic thrill of secret knowledge. It is less glamorous to reckon with wage stagnation, predatory housing markets, brittle public services, and the quiet capture of democratic institutions by concentrated wealth. Yet, these are the forces that make people anxious, isolated, and susceptible to stories that promise meaning, certainty, and someone to blame. As I argued in the video, fear narratives flourish where life is precarious; if families could rely on rising wages, dependable infrastructure, and a dignified retirement, there would be far less oxygen for moral panics and profit-driven prophecies.

Nor is the trade in fear confined to evangelical fundamentalism. The modern occult scene harbours its own hucksters, eager to sell a password to hidden wisdom if payment arrives before next Tuesday, and conspiracy-minded spirituality often recycles the same dramaturgy with a shifting cast of antagonists.

The roles change—demons, migrants, transgender people, musicians—yet the script remains constant: identify an enemy, declare an imminent catastrophe, monetise insider status. Thelema’s call to True Will stands at a principled distance from this economy of panic.

To do one’s Will is to act from clarity rather than anxiety, to accept responsibility in place of scapegoating, to build communities that practise mutual aid and sane spiritual discipline, and to measure progress not by the frenzy of headlines but by the steady work of becoming who you are meant to be.

Towards a Mature SpiritualityThe stories we tell about time do more than decorate our theologies; they script our habits, shape our expectations, and train our imaginations toward either responsibility or retreat. A theology of escapism teaches people to hold the world at arm’s length, treating injustice as a passing weather system rather than the consequence of choices and structures, and cultivating the passive vigilance of those who prefer rescue to reform.

A spirituality of Aeonic transformation points in the opposite direction, inviting us to become conscious participants in the unfolding of awareness, to notice how epochs change as people change, and to accept that the great work before us is double, within and without, a conversation between inner clarity and outer practice that remakes both the self and the polis.

Here are some ideas:

Engage in social justice: Recognise that much of the suffering in our world is not the work of unseen agencies but the predictable outcome of policies, incentives, and power imbalances. Acting under Will means directing energy where it can alter conditions, supporting movements that raise minimum wages, secure broad access to healthcare, stabilise housing, curb predatory practices, and resist the capture of democratic institutions by private wealth. This is not a flight from the spiritual to the political; it is the application of conscience to the arena where consequences are measurable, from local council meetings and union halls to courtrooms and clinics, with the understanding that every incremental gain in the commons widens the field in which human flourishing can occur.

Cultivate mutual aid: Build circles of reciprocity that treat care as a daily liturgy rather than a last-minute scramble for supplies in anticipation of a cosmic bailout. Feed those who are hungry, help secure shelter for the unhoused, organise rides, share tools, pool small grants, and keep an eye on the elders and the vulnerable on your street. Mutual aid differs from charity because it assumes equality, not hierarchy; it is a covenant among neighbours rather than a display of magnanimity. In Thelemic terms, it is the social expression of love under will, a practice that dignifies both the giver and the receiver, and turns community from a slogan into a durable infrastructure of trust.

Pursue inner work: The Aeon of Horus is not a permission slip to drift; it demands discipline sufficient to reveal what is yours to do. Meditation, journaling, ritual practice, breathwork, honest self-examination, and periods of silence are not luxuries, but rather instruments that bring the True Will into focus. Record your experiments as Crowley advised, compare intention with result, and refine the practice accordingly. Thelemic magick and mysticism are empirical, a long conversation between hypothesis and experience. As the record deepens, so does discernment, and with discernment comes the freedom to spend your life on what genuinely belongs to you.

Reject fear-based spirituality: Whether it appears in a pulpit or a temple, a livestream or a lodge, refuse programs that trade in terror, exclusivity, and the promise of insider status to those who pay or comply. Fear narrows attention, corrodes judgment, and makes people easy to manage; authentic spirituality does the reverse, widening the field of choice and strengthening the capacity to choose well. Seek teachers and communities that empower rather than intimidate, that welcome questions, and that measure authority by service rather than by spectacle. In practical terms, this translates to clearer boundaries with grifters, a reduced appetite for crisis theatre, and a renewed commitment to practices that make you calmer, kinder, and more effective in the world that is actually here.

I hope this expanded article deepens your understanding of both the historical origins of the Rapture and the transformative power of Thelema’s Aeonic vision.

If the conversation resonates with you, consider watching the New Aeon Agora video that inspired it, liking, sharing, and commenting with your own stories of apocalyptic predictions and spiritual awakenings.

Let’s replace fear with responsibility every time .

Thanks for reading Magick Without Tears with Marco Visconti. This post is public, so feel free to share it.