Byard’s Leap: The Winding History of a Single Bound

The legend of Byard’s Leap is as much about a heroic horse as it is about a horrible hag. I’ll try to summarize the narrative, even though — as we’ll explore — there are several variations on it.

Northwest of Sleaford, in Lincolnshire, England, is a spot known as Byards Leap. The curious name is a reference to a tremendous jump made by a horse once upon a time. You see, the local people were plagued by a nasty witch, one along the lines of, say, Black Annis, in that she lived in a cave, had long talon-like fingernails, and, some say, feasted on children.Luckily, a hero rose to vanquish the witch. At a nearby pond where horses gathered, he tossed a rock into the water to observe and select the steed with the quickest response time and/or with divine approval for the task at hand. The one he chose was named Byard (sometimes spelled Bayard or Biard).

The hero mounted Byard and rode off to confront the witch. There, a struggle began, and the witch dug her creepy fingernails into Byard. The poor horse lunged into the air and landed far, far away! In the process, the witch perished.

But the hoofprints left from Byard's Leap remain to this day. In fact, there are photos in this well-researched article written by Rory Waterman for the Lincolnshire Folk Tales Project.

As one expects, this legend evolved over time, different renditions swapping out specifics. I figured it might be interesting and hopefully useful to researchers if I were to dig up what I could on the printed history of the oral tradition. Below, then, is an informal annotated bibliography, chronologically ordered, of the Byard’s Leap narrative.

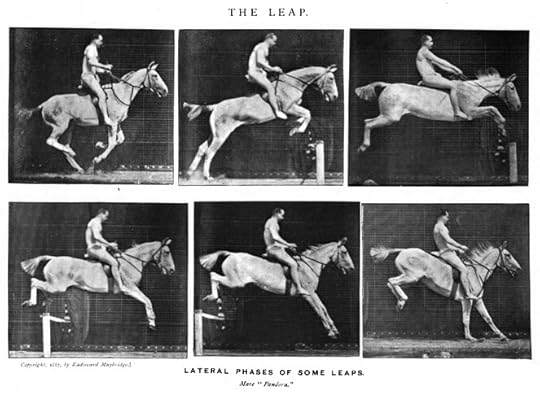

Tragically, no photograph seems to exist of Byard’s legendary leap (which suggests poor planning on the hero’s part). This substitute comes from Eadweard Muybridge’s Animals in Motion: An Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Progressive Movements (1899)Permutations Across Centuries

Tragically, no photograph seems to exist of Byard’s legendary leap (which suggests poor planning on the hero’s part). This substitute comes from Eadweard Muybridge’s Animals in Motion: An Electro-photographic Investigation of Consecutive Phases of Animal Progressive Movements (1899)Permutations Across Centuries1704: Anonymous, . This source is a travel journal purportedly written in 1704 and finally published in 1818. The unnamed author makes a quick reference to Byard’s hoofprints, which are “16 yards” apart. Knowing his readers might scoff at such a distance, the traveler teases: “But then, you must know, the horse was frightened by a witch, or perhaps he never leap so farr; and the people hereabouts keep the marke of the leap, on purpose to be seen.”

1776: William Stukeley’s Itinerarium Curiosum; Or, An Account of the Antiquities and Remarkable Curiosities in Nature and Art, Observed in Travels through Great Britain. Another travelogue, this one from the latter half of the eighteenth century, also refers to the spot. Stukeley writes: “[H]ere is a cross of stone, and by it four little holes made in the ground: they tell silly stories of a witch and horse making a prodigious leap, and that his feet rested in these holes, which I think rather the boundaries for four parishes….” Apparently, Stukeley didn’t know how to have fun.

1846: G. Oliver’s The Existing Remains of the Ancient Britons, Within a Small District Lying Between Lincoln and Sleaford. Oliver provides a much more detailed rendition of the legend. Here, we learn that “our witch was very cunning in the capture of children, which she carried to her cave and devoured.” Our hero is described as “A knight of tried courage, during the age of chivalry….” Our horse now jumps “at least 60 yards,” and does so three times.

1863: Edward Trollope’s “Lincoln Heath, and Its Historical Associations.” Though Trollope doesn’t mention any snacking on children, the witch here “was seen cowering over a fire emitting a blue unearthly light, and sometimes flitting bat-like through the shades of night, intent on mischief towards man and beast.” No precise yardage is mentioned, but “the witch’s claws deepen in the shoulders of the knight and the flanks of the horse; when happily the former calls to mind a cross road near at hand, and if he can but reach this he is safe. He pulls the left rein, therefore, and away bounds Bayard in that direction, until with one prodigious effort he clears the point of junction, and the witch falls dead before the leap is accomplished.” In other words, Byard’s mighty bound over a mystically powerful crossroad defeats the witchy foe.

1878: S.M. Mayhew’s “Welbourne, Lincolnshire, and Its Neighbourhood.” Now, the hero is something of a witch-hunter, one “whose mission appears to have been in delivering earth from sorcerers.” In his skirmish with the witch, Byard jumps three times, “each of about 170 feet.”

1891: J. Conway Walter’s “The Legend of Byard’s Leap.” Byard’s record is now set at “sixty feet,” and — replacing the knight — a “shepherd is selected for the enterprise” of defeating the witch. This revision makes the hero a much more humble one — instead of Bruce Wayne, he’s Peter Parker (before the big bite!) — and this builds tension, given his inexperience with slaying stuff. Also, unless I missed something, this is my first source that says Byard is blind, and Walter explains that this is “a providential circumstance, since it is likely that any horse which could see would shrink from contact with the witch.” Instead of a deadly crossroad, the witch falls off Byard and down into a pond, where she drowns. Witches and water have an uneasy history.

1895: Sidney Oldall Addy’s “25–Byard’s Leap.” As with Walter, the hero shifts from a gallant knight to an ordinary bloke, specifically, one of the local farmers. Byard is once again blind. That horse’s three leaps now measure “seven yards.” A simple knife wound costs the witch her powers, though perhaps not her life. I like to think she found a new career as a manicurist.

1904: M.P.’s “63. Bayard’s Leap and the Late Canon Atkinson’s View of the Legend.” M.P.’s goal is to establish the earliest known version of the ever-evolving tale. The witch is back to eating people and residing in a cave, and the hero is back to being a wandering knight. There’s a quick note that the special horse was “sometimes called the blind Bayard,” and another one about versions disagreeing about whether the horse jumped three times or only once. Here, the witch dies from the knight’s sword.

Reboots Are Nothing NewI’m sure there are more transcriptions of the legend out there, but this is enough to suggest how it morphed over time. What makes the witch so dreaded? Who slays her, and how does she die? Is Byard blind or not? These are questions different narrators answer differently. Nonetheless, the story retains its essentials: a bad witch, a brave hero, a chosen horse, a deep stab, a mighty leap, and a dead witch. Oh, and holes in the ground to “prove it.”

In fact, the legend continues to take on new forms. None of the sources above provides a name for the witch, but these days, you’ll find her called Old Meg or Black Meg. The former is found in this version along with a full backstory for her, one in which the conquering knight is her former sweetheart — and really quite a jerk!

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THE

CLICK ON THE WITCH TO VISIT THEWHISPERS OF WITCHERY

MAIN PAGE.