THERE IS A CRACK, A CRACK IN EVERYTHING

I love Leonard Cohen’s lyrics, particularly those two lines. Their meaning, relevance and resonance grew even more after my brain attack in September 2024.

Naively, I’d expected to recover fully within three months. Christmas passed but my life still had a metaphorical crack. During those dark post-Christmas days, even more fissures appeared. Try as I might, I was struggling to see even a glimmer of light.

In hospital, I’d heard medics use the term, ‘mild stroke’ and taken them at their words. I guess they were right, medically speaking. Factually, the severity of brain attacks varies, some are catastrophic, each is unique. Mild is not a word I’d use for mine.

But I’d also heard doctors talk about ‘progress’ and ‘first three months’ and assumed the best. With hindsight, I’d probably misinterpreted; or more likely it was more a case of wishful thinking.

Either way, reality began to bite just before the festivities when we travelled to St Ives for a few days. Apart from it being one of our favourite places in the world, we were there to celebrate a big birthday – our daughter’s. The plush apartment we stayed in came with beautifully bedecked Christmas tree, classy décor plus amazing views of the sea.

Room with a view

Room with a viewI’d fondly imagined pottering into town, indulging in a little retail therapy, breaking off now and then for cappuccino or cocktails.

Only I didn’t.

In the real world, I’d not set foot in a shop, coffee house or wine bar for weeks. In St Ives it was a similar story: walking any distance of note was beyond me, shopping was out of the question; I drank coffee at the apartment, we took taxis to favourite restaurants.

It felt so good to get away, we had lots of fun and laughter, great food, lively conversations but I can’t pretend all was sweetness and light. I mostly hid gloomy thoughts behind a game face, but, inside, I was bitterly disappointed that I couldn’t do many things I used to take for granted. I was also constantly aware of the cracks.

Back home and those cracks deepened. The early discharge physiotherapy had come to its arranged end in mid-December. I missed it. The wintry days seemed too short, the nights too long, weather too cold, too wet. When it was icy, even my meagre walks fell by the wayside. (I’d fallen on black ice fifteen years previously and broken my left hip. Not an experience to repeat. Or being blue lit to hospital for emergency surgery.)

Confined to the house, I freely admit harbouring some really dark thoughts: my mobility was severely restricted, activities seriously curtailed, my world had shrunk; the outlook appeared bleak. Increasingly, I was short-tempered, snappy. I cried a lot. Questioned whether I wanted to stick around for the long run.

I must stress that not for a second did I think about taking my own life but – being completely honest – there were fleeting moments when I wondered if it would have been better all round if I’d died that night in September.

And then I had my epiphany.

Not on January 6th, it came later that month on the 20th in the shape of a senior physiotherapist at the nearby community hospital. I’ll call him Mark though that’s not his real name. As an outpatient, I saw him for hourly sessions almost every week through to the middle of May. I arrived for the first bowed down by woes and left with the proverbial – and virtual – spring in my step.

There were no exercises that day, but there was a verbal workout.

In no uncertain terms, Mark said my recovery could take a year, maybe two. It would be on-going and might never be full.

His words meant the world to me. A dark cloud of what had clearly been depression, if not despair, lifted. I could see light through the cracks.

For the first time since the brain attack, I now had realistic expectations and no longer felt that every shortcoming was my failure.

As Mark put it: Recovery is a marathon not a sprint. It would happen in fits and starts and there’d be plateaux. The only way it would grind to a halt was if I gave up.

I’m a grafter; giving up had never been in my vocabulary. Nor ‘this’ll do’ – no point in doing anything if it’s not done well.

And so the next stage of recovery began.

Weighty words

Mark didn’t just talk the talk, the next week we walked. And the next. And the next. In the gym, we’d work on specific exercises to strengthen my muscles, improve balance and increase flexibility. We still talked a lot. I left every session armed with ‘homework’ – and a wide smile.

A nurse’s words came back to me.

A doctor saves lives. A physiotherapist makes lives worth living.

When I heard this in hospital, it hadn’t really struck a chord. It played a full orchestra now.

Over the next few months, with Mark’s words ringing in my ears, my confidence grew, I scored more goals: walking to a favourite coffee shop, strolling in the park. First visits to the cinema, theatre and gigs. Several breaks in places like Ludlow, the Lake District, Bristol and Bath and of course my beloved Cornwall.

Santé!

Santé!

Park life

Park life

Gig fun

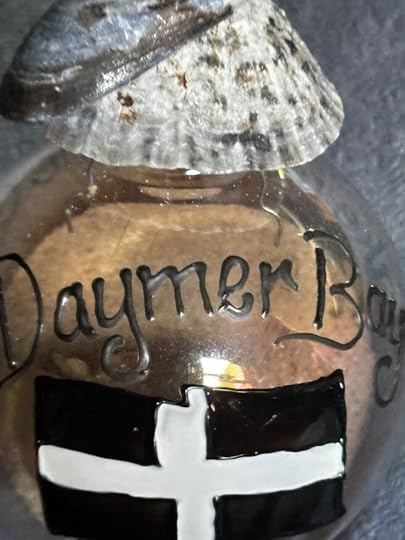

Gig funI had the brain attack just over a year ago and to mark its anniversary we spent a defiant (if reflective) seven days in Polzeath.

From there to Daymer Bay is one of my favourite coastal walks in the country. Secretly, I’d had it in mind for weeks to give the walk a go. Well, reader, as my daughter who came along to give me a hand put it, I nailed it. It’s only a distance of 1.7 miles but getting to the finishing line gave me as much pleasure and sense of achievement as running a marathon. Next year maybe? No. I know my limitations, but . . .

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

On your marks . . .

On your marks . . .

En route

En route

Home and dry

Home and dry

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

Coming soon: Part 4, Seeing the light, literally