GREAT EXPECTATIONS TO HARD TIMES

Losing the clot, part 2

Ironically it wasn’t until I left the snug quasi-cocoon of a hospital ward that the full import of what had happened sank in. Once home and faced, for instance, with tackling a steep flight of stairs every time I needed the loo, cold reality began to dawn – brain damage had disabled my body.

I stopped using the fluffy term ‘stroke’; a better description by far was brain attack. Best response? A full and fast recovery. From now on, I’d be fighting back; the gloves were off.

Just like that.

I was in full Tommy Cooper mode. (Google Tommy Cooper British comedian if you don’t get the reference.) Anyway, that was my mode and mood. It came as quite a shock to realise my brain had failed to get the memo.

Indeed, ‘just like that’, appeared to be an alien concept: my impaired brain wasn’t just failing to receive myriad messages – it wasn’t sending out nearly as many as it should. Rather than being on the same page it appeared to be on a different planet.

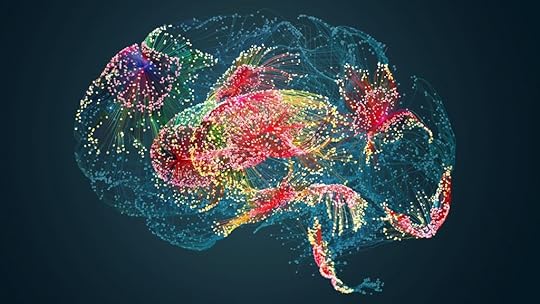

After a good deal of introspection and even more internet investigation, it occurred to me that my brain-body disconnect was hardly surprising. Brian the clot had been on the rampage recklessly wreaking GBBH: grievous bodily and brain harm on god knows how many neurons. God being the operative word: the human brain houses so many nerve cells the number’s too vast for a mere mortal to get their head round (pun alert) let alone visualise.

Some neuroscientists estimate around 86 billion neurons; a figure that’s been likened to the number of stars in the Milky Way. A pleasing image, easy to picture perhaps but given the MW contains up to 400 billion twinkling stars, the comparison is more than a tad off-beam. And there’s more mind-boggling numbers . . .

Starry, starry night

Starry, starry nightThrow synapses – crucial connections between neurons – into the mix and then we’re talking. Or maybe not. The human brain has an estimated quadrillion (1,000, 000, 000, 000, 000) synapses – a sum that left me speechless. Almost.

Fact is cells and synapses must talk among themselves so they can create neural pathways. Those pathways are crucial – it’s how signals are sent between our brain and every part of part of our body. Think of it like an ultra-complex motorway system: Spaghetti Junction on rocket-fuelled steroids wouldn’t even come close; galactic highway, maybe.

cerebral roadmap

cerebral roadmapContinuing the roads’ analogy, fifty percent of my carriageways were scarred with potholes, strewn with debris and had no overhead gantries. That’s no laughing matter, grey or otherwise.

In effect, although the righthand side of my body was in pretty good shape, the left was a car crash. I could talk the talk but barely walk the walk. I needed a helping hand to wash, eat, exist. My own left hand couldn’t even thumb a lift.

Help was not in short supply. Primarily from people, but also a bunch of unfamiliar aids appeared around the house: a corner stool for the shower, another for drying and dressing; a trolley so I could shuffle my wonky way around the kitchen plus an all-important second stair rail fixed by my husband who, overnight, had become my primary carer.

Initially, he was behind me literally every step of the way going upstairs and played the lead role coming down. It took a fortnight before I had enough confidence to go solo.

As well as his constant support, physiotherapists made house calls three times a week for eight weeks as part of the NHS early discharge scheme. The hour-long sessions were aimed at getting me back on my feet physical and psychological.

For education, education, education, read rehabilitation, rehabilitation, rehabilitation which meant exercise, exercise, exercise. It wasn’t a question of push-ups or Lotus positions.

In the early days, getting up from a chair was a stretch. As for crossing my legs, crossing my fingers was a big ask.

No, the focus was on small, slow, repetitive movements. Many times, multiple occasions, every day; rinse and repeat ad infinitum.

One example: although I had little problem moving my left arm and shoulder, manual dexterity wasn’t a strong suit, my fingers were stiff and uncooperative. Those pesky neural pathways again.

What to do? In my case, take a pair of eyebrow tweezers, twenty or so grains of rice, a small dish and a flat surface. Grasp tweezers in left hand, transfer rice grain by grain to dish then return grain by grain to flat surface. And after countless hours spent ferrying rice? The pay-off was a fully-functioning set of fingers – more or less. Diligently moulding Play-Doh into tiny balls also helped, but that’s a different story.

Rising and sitting in chairs became a doddle – albeit it gingerly at first – after going through the motions ten times, then twenty, then thirty times a day. Or more. For weeks. But, hey, a result’s a result.

Encouraged by my unfailingly positive and perky physios, I set hourly, weekly, monthly targets. It was hard graft, could be mind-numbingly boring and not infrequently I was beyond frustration; tears flowed on several occasions.

But there were flashes of pure joy too when I notched up another unaided ‘first’. That could be anything from fastening a button to filling a kettle, showering to making pastry for mince pies.

Perceptible progress in those early weeks kept me going. That and a streak of bloody-mindedness to beat the faeces out of Brian the clot.

I hit many targets, scored goals with the ease of a Ronaldo but my run rate was non-existent. Not when walking still proved a real challenge.

I knew how to walk, it was my brain that had apparently forgotten. I talked out loud to it, issued simple instructions; switched between cajoling and cursing, tough love and harsh admonitions. And when all else failed I screamed and bawled like a toddler having a tantrum.

If only I could toddle.

And eventually I did. At least I started taking baby steps without assistance apart from my cane. (A rather splendid sparkling purple cane that I bought online the day I left hospital. Well, have you seen an NHS walking stick?)

I’d like to think my sweet-talking had helped open a few million neural pathways between my brain and lower left limb, it was more down to intensive physiotherapy, exhaustive exercise regimes and equally importantly the brain’s own ability to form new connections and reorganise or strengthen existing ones in response – among other things – to injury.

Put simply, it’s a massive rewiring job. Medically speaking it’s known as neuroplasticity. (More on this in a later post.) Current problem? Rewiring on this scale is incredibly intricate plus there’s no way of knowing if it will work, how well it will work or how long the job will last.

Everyone is different as is every brain attack and rate of recovery.

In my case, I wasn’t able enough to set foot outside the door for seven weeks. That first foray was to the end of the road, around forty-five metres, not much more than sixty steps. I had my cane in one hand and clutched a physio’s arm with the other. It’s impossible to convey how wonderful it felt to be al fresco.

Purple reign

Purple reignAt the same time, my elation was tempered by vague unease. One short, painfully slow walk had left me exhausted. The next was equally laborious. And the next. And the next. Yet, Christmas was fast approaching. Christmas when I’d be fully recovered, yes? Back to my old self, right as rain, fighting fit. I clung desperately to every cliché in the book.

But as Christmas came and went, so did my Great Expectations. My high hopes took a deep dive. It became increasingly clear that hard times lay ahead. I’d no idea how hard and dark they’d be. Then three things happened. Three things that changed my life – only this time for the immeasurably better. And literally brighter.

Coming soon: Part 3, Seeing the light(s)

Bay watch

Bay watch