Maureen Carter's Blog

October 31, 2025

A WORK IN PROGRESS

CLOT LINES

During my novel writing life, it was par for the course to have a WIP – an unfinished script – lying around in my study. A year and fifty-one days on from the brain attack, a WIP is how I see myself: a work in progress.

I admit, albeit a tad reluctantly (and testily), that high hopes of a complete and rapid recovery remain just that: although the hopes are a notch or three lower down. I still feel a return to fighting fitness is just about doable but, speedy? That ship has circumnavigated the globe. It’s exasperating when I’m itching to move on apace.

‘Patience is a virtue’, goes the saying and if I repeat it often, I might start to believe it again. A mantra of mine for months has been, slow but sure. It worked well for a while, I know how far I’ve come along progress road, but I’ve reached the point where I long for the fast lane, or at least swifter than the current rate. More hare (or Toad) less tortoise, I say.

The snag is that my brain now functions only so far on autopilot; it needs to ponder every step of the way. All that loose or disconnected wiring means it sends and receives messages via snail mail rather than email and that leads to everything taking longer and expending more energy.

One study found that tasks after a brain attack use five times more energy than prior which mainly explains why chronic fatigue is an issue for most people in the brain attack boat.

I’m not talking a touch more tired; I’m talking tsunamis of overwhelming exhaustion. There’s no fighting it. Believe me I tried, but battling through isn’t just pointless, it’s counterproductive. Initially, the knock-on effect of not taking a break could write off the rest of the day. And the next. I had to learn to take things easy, which as we know is easier said than done.

Physios promote the three Ps: prioritise, plan, pace. Excellent advice which I still follow. What with PPP, ESD, MRI et al, initials have been all the rage this last year or so. I even made up my own: BBA and PBA.

Life BBA was pretty good, all body parts in working order, brain ticking over nicely. I had independence, spontaneity and a smorgasbord of options. PBA, not so much.

I like to believe the essential me remains the same: personality, thought processes, sense of humour, smooth tongue, sharp wit. Modesty. I’m still a hopelessly addicted news junkie, voracious reader, ardent ‘goer’ to theatre, cinema and gigs.

Plus ça change?

Plus ça change?All this and more is, I believe, unchanged. Maybe it’s wishful thinking. How I see my PBA self isn’t always the way others do. I know this with certainty because I’m hyper-alert to people’s reactions.

I walk slowly, have a slight limp and use a stick. It may be purple and shiny and rather chic, but it’s still a stick. Visual shorthand for not the norm: different. And although I used to baulk at the word, I’ll call it what it is – disabled.

Many people still show ‘the kindness of strangers’, and it’s a wonderful thing. But not all. I’ve clocked occasional glances of pity, sometimes impatience, even contempt. I’ve heard people whisper the sort of line that goes, ‘does she take sugar?’ (I have the hearing of a bat colony and, no, I don’t take sugar.)

People I know well, I watch like a hawk readying to pounce. I’ve been known to snap a testy ‘don’t patronise me’ or ‘no, I can do it’.

Almost invariably it’s a case of me jumping to conclusions over a perceived slight. I can mistake care and concern for casual disdain. Add hyper-sensitivity to the blend plus my own ultra-awareness and assessment of every move I make and – mea culpa, guilty as charged, it’s a fair cop, guv.

In truth, although I can manage many everyday tasks that were impossible a year ago, I can’t do them as quickly or efficiently and there are others still beyond me. Again, although I feel the same and, seated, I look the same, when I stand and walk it’s clear – even to me – there’s something amiss.

Every so often, utter frustration and fury unleashes my inner Violet Eizabeth Bott. The tantrum doesn’t last long: wallowing in a tear bath is unsightly and wastes both time and that all-important energy. I usually nip a crying bout in the bud with a self-coined maxim: Don’t grieve for what you’ve lost; be grateful for what you have.

And I am. Mostly.

After all, I’m still here and they say what doesn’t kill us makes us strong. Are they right? To an extent. I have more resilience, insight and empathy. At the same time, I feel more vulnerable, more fragile, more fearful. Maybe they’re natural emotions given the state of the world, but that’s a much bigger story.

This story’s almost complete, but bear with me a minute: I’ve been cogitating of late on the relationship between the mind and the brain. I don’t pretend to understand the complexities – who does? – but broadly-speaking the brain’s a tangible, physical organ. The mind a collection of thoughts, memories, emotions. Though different they’re inextricably linked, and each needs the other to function fully.

I’m being simplistic, but I see it as the brain controlling the body and the mind running everything else. Even so, to my way of thinking, I reckon the brain has the upper hand, as it were.

If it was a case of mind over matter, I’d be signing up for the New York marathon and treading the boards at Stratford as Lady Macbeth. (The imagination’s as lively as ever.)

No, the reality is that although I’ve shown Brian the door, the bloody clot left damage in its wake. Whether the damage is permanent or not, only time and my rewiring efforts will tell. And that’s something I’ll always be working on.

Out, out damn clot

Out, out damn clotThis is my last regular brain attack blog, but I’ll keep you posted with significant updates.

In the meantime, I leave you with one of my favourite quotes. It’s from the poet Lemn Sissay’s memoir, My Name Is Why. His fourteen words speak volumes.

I am not defined by my scars, but by the incredible ability to heal.

Breaking news . . . I’ve just been given the medical green light to drive again. Thrilled? You bet! On the joys of the open road, I’m with Toad in the driving seat.

‘Poop, poop. Oh, poetry of motion! Oh, the bliss!’

Highway Toad

Highway ToadPoop, poop, indeed.

October 23, 2025

IN HEALTH AND IN SICKNESS – WHO CARES?

The doctored heading is mine, but who better to write this post than my husband of more than forty years? In his own words, for one night only, (drum roll) it’s over to Peter Shannon.

When Maureen woke me at three in the morning and said, ‘Peter, I need help,’ I knew, instinctively, that our lives had changed forever.

Realising that Maureen had had a stroke was possibly as much a shock to me as it was to her. [It wasn’t. Ed.] Trying to work out what all the implications were had my mind in a spin. I remember sitting in the ambulance outside A&E thinking, foolishly, that maybe we’d be back home that night.

Our daughter was amazing during this early period. She helped me to get through that first day and, boy, I needed all the help I could get. She didn’t get back from work until after midnight, but despite the exhaustion I waited up so we could have a big hug and a chance to talk about all that had happened.

I can’t help but be thankful to all the people initially involved – the paramedics and hospital staff were incredibly kind, informative and caring. They made such a difference to me as I was trying to come to terms with our new reality.

Looking back, I wonder could, and should, I have been more aware of what was happening. Maureen hadn’t previously shown any of the most common indications of a stroke. The FAST acronym (Face, Arms, Speech, Time) is a useful guide but women can present with different symptoms. The truth is I have no idea, but I can’t help feeling that somehow I failed. [You didn’t. Ed.]

Given how many people suffer from a stroke or brain attack, as Maureen quite rightly calls it, I would urge everyone to familiarise themselves with these signs. Check out the Stroke Association website: https://www.stroke.org.uk

How do you cope with such an unexpected and frightening event? I don’t imagine many people would even think about it until it happens. At first, I was thinking ok, it’s going to take three months or so before things get back to normal. I could cope with that. I know Maureen felt the same. Both our expectations were unrealistic as Maureen has described. Coming to terms with the idea that Maureen’s recovery was going to be a long and ill-defined process was hard to start with but eventually we just had to get on with it.

So, it was a case of taking one step at a time, sometimes small steps and at others a giant leap. Like the first time we went away not that many weeks after Maureen came home from hospital. We went to Manchester to see Jake Bugg and it was wonderful to be able to share and enjoy such a ‘normal’ time together. Since then, we ‘ve enjoyed many trips and gigs and though the logistics can be challenging they’re worth it.

I know I said my life had changed and it has, but that isn’t necessarily a bad thing. Everything that life chucks at you can be seen either as a pain or an opportunity, so make the most of it.

My experience of being Maureen’s carer has taught me a few valuable lessons. You should try never to let the person you’re caring for feel as if they’re hard work, [I am. Ed.] try to anticipate what they want and need and always go big on encouragement, it can make such a difference.

Fortunately, I can cook and do household stuff but if you can’t, there are other ways to get support; family and friends would be a first call but there will be more resources locally. Once again, the Stroke Association website is packed with information.

How does it feel to be a carer? Tricky one. It’s not easy seeing someone you love having to endure the impact and indignities that a brain attack makes on a body. Be prepared for the long haul, recovery is a complicated drawn-out process. But it happens, I’ve witnessed the gains and losses, the highs and lows. Be patient but also be aware you may need support yourself.

I’ve just arrived home from a few days away walking on Dartmoor, a much-needed break, but surprisingly I was looking forward to getting back and picking up the reins again.

In sickness and in health, for better and worse.

We did

We didI must add, Peter’s been a star throughout the last year or so. I genuiney couldn’t have managed without him. His name’s from the Greek word, Petros, and he certainly lives up to it. Peter has been and still is my rock.

Next on the blog will be the 6th and final part in this series: A WORK-IN-PROGRESS

October 10, 2025

SEEING THE LIGHT, LITERALLY

Seeing the light for sure, but I certainly didn’t spot the brain attack heading my way. Mind for two years beforehand, I’d not been viewing anything particularly clearly. I’d been advised by an ophthalmologist that I needed cataract surgery but being a complete wuss, I’d dithered, dallied and delayed until it reached the point where I really should’ve gone to Specsavers. Or at least returned a lot sooner.

Looking back, I realise that in a weird way the brain attack’s proverbial bolt from the blue did me a big favour . . .

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been prone to iatrophobia, experienced the full works: nausea, dry mouth, dizziness, you name it. Forget white coat syndrome, at so much as a glimpse of scrubs, I morphed into a quivering wreck

Trust me, there’s nothing irrational about my fear of doctors. Even my hospital consultant recognised the signs and agreed to my pleas to cut back on four-hourly blood pressure checks. From then on, they were taken twice a day. For the good of my health.

Nonetheless, surrounded by medicos, monitors and machines, enduring obs, meds and bloods equalled almost my worst nightmare. CT scans and X-rays were bad enough, but when I was told I needed an MRI scan, I was in night terror territory. I hated every second of the imaging.

On the plus side, after going through the horror of my personal hell and living to tell the tale, I reckoned cataract surgery would be a doddle; a gentle breeze, a stroll in the park yada-yada.

It wasn’t. When the day arrived and I clocked the surgeon’s blade approach for the first incision, I flirted momentarily with the idea of doing a runner. Recalled I could barely walk without a cane. Mentally, I donned big girls’ pants, lay back and, as they used to say, thought of England. Or in my case, visualised an exquisite stretch of Cornish coastline.

Back in the real world sipping post-op tea in the recovery area, I quickly agreed (with myself) that compared with an MRI the fifteen-minute painless procedure had been eminently bearable. Good thing, too, as I had to go back six weeks later for surgery on the second eye.

Eye-eye

Eye-eyeAlthough it had been a massive deal for me, for the NHS cataract surgery is minuscule beer. It carries out 1200 operations like mine every day, that’s around 450,000 a year making it the common surgical procedure in the UK.

I’ve been extolling its virtues ever since because the benefits are beyond belief. My pithy advice to anyone putting it off – just do it.

I’d become inured to seeing through a slight fog, everything a tad blurred. I found it difficult adjusting between bright sunlight and shade. I read mostly on my Kindle because I could increase font size. Reading was non-negotiable as I couldn’t imagine life with it.

Lens replacement surgery proved a revelation in more ways than one. Within hours everything around me was clearer, brighter; colours were vibrant again; perspectives sharpened; I could read even the smallest print without glasses.

I likened it to living in a house and having the windows cleaned properly for the first time in years. The quality of my life improved almost – forgive the expression – at a stroke.

As far as health goes, the brain attack was undoubtedly the worst thing that’s ever happened to me, having cataract surgery was – still is – categorically the best.

Brian the clot might have run amok in my head severing countless complex cerebral connections, but it forced me to face up to and conquer feared medical interventions and that brought major gains.

I can see clearly now: cinema and theatre trips, coastal walks and crossword are even more enjoyable, reading, an unalloyed delight. The new lenses have enhanced the quality of my post-brain attack life immeasurably.

I see that as one in the eye for Brian.

In the black corner

In the black corner Up next, part 5, from a guest blogger

In health and in sickness – who cares?

October 3, 2025

THERE IS A CRACK, A CRACK IN EVERYTHING

I love Leonard Cohen’s lyrics, particularly those two lines. Their meaning, relevance and resonance grew even more after my brain attack in September 2024.

Naively, I’d expected to recover fully within three months. Christmas passed but my life still had a metaphorical crack. During those dark post-Christmas days, even more fissures appeared. Try as I might, I was struggling to see even a glimmer of light.

In hospital, I’d heard medics use the term, ‘mild stroke’ and taken them at their words. I guess they were right, medically speaking. Factually, the severity of brain attacks varies, some are catastrophic, each is unique. Mild is not a word I’d use for mine.

But I’d also heard doctors talk about ‘progress’ and ‘first three months’ and assumed the best. With hindsight, I’d probably misinterpreted; or more likely it was more a case of wishful thinking.

Either way, reality began to bite just before the festivities when we travelled to St Ives for a few days. Apart from it being one of our favourite places in the world, we were there to celebrate a big birthday – our daughter’s. The plush apartment we stayed in came with beautifully bedecked Christmas tree, classy décor plus amazing views of the sea.

Room with a view

Room with a viewI’d fondly imagined pottering into town, indulging in a little retail therapy, breaking off now and then for cappuccino or cocktails.

Only I didn’t.

In the real world, I’d not set foot in a shop, coffee house or wine bar for weeks. In St Ives it was a similar story: walking any distance of note was beyond me, shopping was out of the question; I drank coffee at the apartment, we took taxis to favourite restaurants.

It felt so good to get away, we had lots of fun and laughter, great food, lively conversations but I can’t pretend all was sweetness and light. I mostly hid gloomy thoughts behind a game face, but, inside, I was bitterly disappointed that I couldn’t do many things I used to take for granted. I was also constantly aware of the cracks.

Back home and those cracks deepened. The early discharge physiotherapy had come to its arranged end in mid-December. I missed it. The wintry days seemed too short, the nights too long, weather too cold, too wet. When it was icy, even my meagre walks fell by the wayside. (I’d fallen on black ice fifteen years previously and broken my left hip. Not an experience to repeat. Or being blue lit to hospital for emergency surgery.)

Confined to the house, I freely admit harbouring some really dark thoughts: my mobility was severely restricted, activities seriously curtailed, my world had shrunk; the outlook appeared bleak. Increasingly, I was short-tempered, snappy. I cried a lot. Questioned whether I wanted to stick around for the long run.

I must stress that not for a second did I think about taking my own life but – being completely honest – there were fleeting moments when I wondered if it would have been better all round if I’d died that night in September.

And then I had my epiphany.

Not on January 6th, it came later that month on the 20th in the shape of a senior physiotherapist at the nearby community hospital. I’ll call him Mark though that’s not his real name. As an outpatient, I saw him for hourly sessions almost every week through to the middle of May. I arrived for the first bowed down by woes and left with the proverbial – and virtual – spring in my step.

There were no exercises that day, but there was a verbal workout.

In no uncertain terms, Mark said my recovery could take a year, maybe two. It would be on-going and might never be full.

His words meant the world to me. A dark cloud of what had clearly been depression, if not despair, lifted. I could see light through the cracks.

For the first time since the brain attack, I now had realistic expectations and no longer felt that every shortcoming was my failure.

As Mark put it: Recovery is a marathon not a sprint. It would happen in fits and starts and there’d be plateaux. The only way it would grind to a halt was if I gave up.

I’m a grafter; giving up had never been in my vocabulary. Nor ‘this’ll do’ – no point in doing anything if it’s not done well.

And so the next stage of recovery began.

Weighty words

Mark didn’t just talk the talk, the next week we walked. And the next. And the next. In the gym, we’d work on specific exercises to strengthen my muscles, improve balance and increase flexibility. We still talked a lot. I left every session armed with ‘homework’ – and a wide smile.

A nurse’s words came back to me.

A doctor saves lives. A physiotherapist makes lives worth living.

When I heard this in hospital, it hadn’t really struck a chord. It played a full orchestra now.

Over the next few months, with Mark’s words ringing in my ears, my confidence grew, I scored more goals: walking to a favourite coffee shop, strolling in the park. First visits to the cinema, theatre and gigs. Several breaks in places like Ludlow, the Lake District, Bristol and Bath and of course my beloved Cornwall.

Santé!

Santé!

Park life

Park life

Gig fun

Gig funI had the brain attack just over a year ago and to mark its anniversary we spent a defiant (if reflective) seven days in Polzeath.

From there to Daymer Bay is one of my favourite coastal walks in the country. Secretly, I’d had it in mind for weeks to give the walk a go. Well, reader, as my daughter who came along to give me a hand put it, I nailed it. It’s only a distance of 1.7 miles but getting to the finishing line gave me as much pleasure and sense of achievement as running a marathon. Next year maybe? No. I know my limitations, but . . .

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack, a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in

On your marks . . .

On your marks . . .

En route

En route

Home and dry

Home and dry

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

Coming soon: Part 4, Seeing the light, literally

September 25, 2025

GREAT EXPECTATIONS TO HARD TIMES

Losing the clot, part 2

Ironically it wasn’t until I left the snug quasi-cocoon of a hospital ward that the full import of what had happened sank in. Once home and faced, for instance, with tackling a steep flight of stairs every time I needed the loo, cold reality began to dawn – brain damage had disabled my body.

I stopped using the fluffy term ‘stroke’; a better description by far was brain attack. Best response? A full and fast recovery. From now on, I’d be fighting back; the gloves were off.

Just like that.

I was in full Tommy Cooper mode. (Google Tommy Cooper British comedian if you don’t get the reference.) Anyway, that was my mode and mood. It came as quite a shock to realise my brain had failed to get the memo.

Indeed, ‘just like that’, appeared to be an alien concept: my impaired brain wasn’t just failing to receive myriad messages – it wasn’t sending out nearly as many as it should. Rather than being on the same page it appeared to be on a different planet.

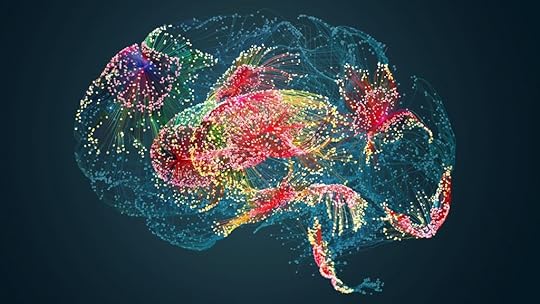

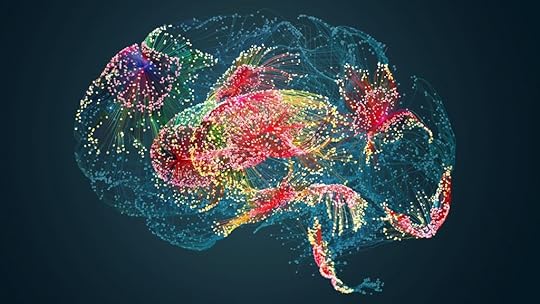

After a good deal of introspection and even more internet investigation, it occurred to me that my brain-body disconnect was hardly surprising. Brian the clot had been on the rampage recklessly wreaking GBBH: grievous bodily and brain harm on god knows how many neurons. God being the operative word: the human brain houses so many nerve cells the number’s too vast for a mere mortal to get their head round (pun alert) let alone visualise.

Some neuroscientists estimate around 86 billion neurons; a figure that’s been likened to the number of stars in the Milky Way. A pleasing image, easy to picture perhaps but given the MW contains up to 400 billion twinkling stars, the comparison is more than a tad off-beam. And there’s more mind-boggling numbers . . .

Starry, starry night

Starry, starry nightThrow synapses – crucial connections between neurons – into the mix and then we’re talking. Or maybe not. The human brain has an estimated quadrillion (1,000, 000, 000, 000, 000) synapses – a sum that left me speechless. Almost.

Fact is cells and synapses must talk among themselves so they can create neural pathways. Those pathways are crucial – it’s how signals are sent between our brain and every part of part of our body. Think of it like an ultra-complex motorway system: Spaghetti Junction on rocket-fuelled steroids wouldn’t even come close; galactic highway, maybe.

cerebral roadmap

cerebral roadmapContinuing the roads’ analogy, fifty percent of my carriageways were scarred with potholes, strewn with debris and had no overhead gantries. That’s no laughing matter, grey or otherwise.

In effect, although the righthand side of my body was in pretty good shape, the left was a car crash. I could talk the talk but barely walk the walk. I needed a helping hand to wash, eat, exist. My own left hand couldn’t even thumb a lift.

Help was not in short supply. Primarily from people, but also a bunch of unfamiliar aids appeared around the house: a corner stool for the shower, another for drying and dressing; a trolley so I could shuffle my wonky way around the kitchen plus an all-important second stair rail fixed by my husband who, overnight, had become my primary carer.

Initially, he was behind me literally every step of the way going upstairs and played the lead role coming down. It took a fortnight before I had enough confidence to go solo.

As well as his constant support, physiotherapists made house calls three times a week for eight weeks as part of the NHS early discharge scheme. The hour-long sessions were aimed at getting me back on my feet physical and psychological.

For education, education, education, read rehabilitation, rehabilitation, rehabilitation which meant exercise, exercise, exercise. It wasn’t a question of push-ups or Lotus positions.

In the early days, getting up from a chair was a stretch. As for crossing my legs, crossing my fingers was a big ask.

No, the focus was on small, slow, repetitive movements. Many times, multiple occasions, every day; rinse and repeat ad infinitum.

One example: although I had little problem moving my left arm and shoulder, manual dexterity wasn’t a strong suit, my fingers were stiff and uncooperative. Those pesky neural pathways again.

What to do? In my case, take a pair of eyebrow tweezers, twenty or so grains of rice, a small dish and a flat surface. Grasp tweezers in left hand, transfer rice grain by grain to dish then return grain by grain to flat surface. And after countless hours spent ferrying rice? The pay-off was a fully-functioning set of fingers – more or less. Diligently moulding Play-Doh into tiny balls also helped, but that’s a different story.

Rising and sitting in chairs became a doddle – albeit it gingerly at first – after going through the motions ten times, then twenty, then thirty times a day. Or more. For weeks. But, hey, a result’s a result.

Encouraged by my unfailingly positive and perky physios, I set hourly, weekly, monthly targets. It was hard graft, could be mind-numbingly boring and not infrequently I was beyond frustration; tears flowed on several occasions.

But there were flashes of pure joy too when I notched up another unaided ‘first’. That could be anything from fastening a button to filling a kettle, showering to making pastry for mince pies.

Perceptible progress in those early weeks kept me going. That and a streak of bloody-mindedness to beat the faeces out of Brian the clot.

I hit many targets, scored goals with the ease of a Ronaldo but my run rate was non-existent. Not when walking still proved a real challenge.

I knew how to walk, it was my brain that had apparently forgotten. I talked out loud to it, issued simple instructions; switched between cajoling and cursing, tough love and harsh admonitions. And when all else failed I screamed and bawled like a toddler having a tantrum.

If only I could toddle.

And eventually I did. At least I started taking baby steps without assistance apart from my cane. (A rather splendid sparkling purple cane that I bought online the day I left hospital. Well, have you seen an NHS walking stick?)

I’d like to think my sweet-talking had helped open a few million neural pathways between my brain and lower left limb, it was more down to intensive physiotherapy, exhaustive exercise regimes and equally importantly the brain’s own ability to form new connections and reorganise or strengthen existing ones in response – among other things – to injury.

Put simply, it’s a massive rewiring job. Medically speaking it’s known as neuroplasticity. (More on this in a later post.) Current problem? Rewiring on this scale is incredibly intricate plus there’s no way of knowing if it will work, how well it will work or how long the job will last.

Everyone is different as is every brain attack and rate of recovery.

In my case, I wasn’t able enough to set foot outside the door for seven weeks. That first foray was to the end of the road, around forty-five metres, not much more than sixty steps. I had my cane in one hand and clutched a physio’s arm with the other. It’s impossible to convey how wonderful it felt to be al fresco.

Purple reign

Purple reignAt the same time, my elation was tempered by vague unease. One short, painfully slow walk had left me exhausted. The next was equally laborious. And the next. And the next. Yet, Christmas was fast approaching. Christmas when I’d be fully recovered, yes? Back to my old self, right as rain, fighting fit. I clung desperately to every cliché in the book.

But as Christmas came and went, so did my Great Expectations. My high hopes took a deep dive. It became increasingly clear that hard times lay ahead. I’d no idea how hard and dark they’d be. Then three things happened. Three things that changed my life – only this time for the immeasurably better. And literally brighter.

Coming soon: Part 3, Seeing the light(s)

Bay watch

Bay watch

Great Expectations to Hard Times.

Losing the clot, part 2

Ironically it wasn’t until I left the snug quasi-cocoon of a hospital ward that the full import of what had happened sank in. Once home and faced, for instance, with tackling a steep flight of stairs every time I needed the loo, cold reality began to dawn – brain damage had disabled my body.

I stopped using the fluffy term ‘stroke’; a better description by far was brain attack. Best response? A full and fast recovery. From now on, I’d be fighting back; the gloves were off.

Just like that.

I was in full Tommy Cooper mode. (Google Tommy Cooper British comedian if you don’t get the reference.) Anyway, that was my mode and mood. It came as quite a shock to realise my brain had failed to get the memo.

Indeed, ‘just like that’, appeared to be an alien concept: my impaired brain wasn’t just failing to receive myriad messages – it wasn’t sending out nearly as many as it should. Rather than being on the same page it appeared to be on a different planet.

After a good deal of introspection and even more internet investigation, it occurred to me that my brain-body disconnect was hardly surprising. Brian the clot had been on the rampage recklessly wreaking GBBH: grievous bodily and brain harm on god knows how many neurons. God being the operative word: the human brain houses so many nerve cells the number’s too vast for a mere mortal to get their head round (pun alert) let alone visualise.

Some neuroscientists estimate around 86 billion neurons; a figure that’s been likened to the number of stars in the Milky Way. A pleasing image, easy to picture perhaps but given the MW contains up to 400 billion twinkling stars, the comparison is more than a tad off-beam. And there’s more mind-boggling numbers . . .

Starry, starry night

Starry, starry nightThrow synapses – crucial connections between neurons – into the mix and then we’re talking. Or maybe not. The human brain has an estimated quadrillion (1,000, 000, 000, 000, 000) synapses – a sum that left me speechless. Almost.

Fact is cells and synapses must talk among themselves so they can create neural pathways. Those pathways are crucial – it’s how signals are sent between our brain and every part of part of our body. Think of it like an ultra-complex motorway system: Spaghetti Junction on rocket-fuelled steroids wouldn’t even come close; galactic highway, maybe.

cerebral roadmap

cerebral roadmapContinuing the roads’ analogy, fifty percent of my carriageways were scarred with potholes, strewn with debris and had no overhead gantries. That’s no laughing matter, grey or otherwise.

In effect, although the righthand side of my body was in pretty good shape, the left was a car crash. I could talk the talk but barely walk the walk. I needed a helping hand to wash, eat, exist. My own left hand couldn’t even thumb a lift.

Help was not in short supply. Primarily from people, but also a bunch of unfamiliar aids appeared around the house: a corner stool for the shower, another for drying and dressing; a trolley so I could shuffle my wonky way around the kitchen plus an all-important second stair rail fixed by my husband who, overnight, had become my primary carer.

Initially, he was behind me literally every step of the way going upstairs and played the lead role coming down. It took a fortnight before I had enough confidence to go solo.

As well as his constant support, physiotherapists made house calls three times a week for eight weeks as part of the NHS early discharge scheme. The hour-long sessions were aimed at getting me back on my feet physical and psychological.

For education, education, education, read rehabilitation, rehabilitation, rehabilitation which meant exercise, exercise, exercise. It wasn’t a question of push-ups or Lotus positions.

In the early days, getting up from a chair was a stretch. As for crossing my legs, crossing my fingers was a big ask.

No, the focus was on small, slow, repetitive movements. Many times, multiple occasions, every day; rinse and repeat ad infinitum.

One example: although I had little problem moving my left arm and shoulder, manual dexterity wasn’t a strong suit, my fingers were stiff and uncooperative. Those pesky neural pathways again.

What to do? In my case, take a pair of eyebrow tweezers, twenty or so grains of rice, a small dish and a flat surface. Grasp tweezers in left hand, transfer rice grain by grain to dish then return grain by grain to flat surface. And after countless hours spent ferrying rice? The pay-off was a fully-functioning set of fingers – more or less. Diligently moulding Play-Doh into tiny balls also helped, but that’s a different story.

Rising and sitting in chairs became a doddle – albeit it gingerly at first – after going through the motions ten times, then twenty, then thirty times a day. Or more. For weeks. But, hey, a result’s a result.

Encouraged by my unfailingly positive and perky physios, I set hourly, weekly, monthly targets. It was hard graft, could be mind-numbingly boring and not infrequently I was beyond frustration; tears flowed on several occasions.

But there were flashes of pure joy too when I notched up another unaided ‘first’. That could be anything from fastening a button to filling a kettle, showering to making pastry for mince pies.

Perceptible progress in those early weeks kept me going. That and a streak of bloody-mindedness to beat the faeces out of Brian the clot.

I hit many targets, scored goals with the ease of a Ronaldo but my run rate was non-existent. Not when walking still proved a real challenge.

I knew how to walk, it was my brain that had apparently forgotten. I talked out loud to it, issued simple instructions; switched between cajoling and cursing, tough love and harsh admonitions. And when all else failed I screamed and bawled like a toddler having a tantrum.

If only I could toddle.

And eventually I did. At least I started taking baby steps without assistance apart from my cane. (A rather splendid sparkling purple cane that I bought online the day I left hospital. Well, have you seen an NHS walking stick?)

I’d like to think my sweet-talking had helped open a few million neural pathways between my brain and lower left limb, it was more down to intensive physiotherapy, exhaustive exercise regimes and equally importantly the brain’s own ability to form new connections and reorganise or strengthen existing ones in response – among other things – to injury.

Put simply, it’s a massive rewiring job. Medically speaking it’s known as neuroplasticity. (More on this in a later post.) Current problem? Rewiring on this scale is incredibly intricate plus there’s no way of knowing if it will work, how well it will work or how long the job will last.

Everyone is different as is every brain attack and rate of recovery.

In my case, I wasn’t able enough to set foot outside the door for seven weeks. That first foray was to the end of the road, around forty-five metres, not much more than sixty steps. I had my cane in one hand and clutched a physio’s arm with the other. It’s impossible to convey how wonderful it felt to be al fresco.

Purple reign

Purple reignAt the same time, my elation was tempered by vague unease. One short, painfully slow walk had left me exhausted. The next was equally laborious. And the next. And the next. Yet, Christmas was fast approaching. Christmas when I’d be fully recovered, yes? Back to my old self, right as rain, fighting fit. I clung desperately to every cliché in the book.

But as Christmas came and went, so did my Great Expectations. My high hopes took a deep dive. It became increasingly clear that hard times lay ahead. I’d no idea how hard and dark they’d be. Then three things happened. Three things that changed my life – only this time for the immeasurably better. And literally brighter.

Coming soon: Part 3, Seeing the light(s)

Bay watch

Bay watch

September 5, 2025

LOSING THE CLOT

Part one

You read that right: clot not plot. Forgive the pun, but what author doesn’t like a little wordplay? I toyed with other headers in the same – here I go again – vein: The clot thickens; Clot twist; Clot hole; Out, out damn clot. The aim was to grab your attention, whet your appetite for this post, but maybe a whimsical preamble is my way of putting off relating a story I never in a million years anticipated would be mine to write. And one that even now, in part, I’m reluctant to share.

Whatever, a fun pun seemed an infinitely preferable way to begin this piece than with the stark fact: My life changing stroke

To be specific, an ischaemic stroke in the right posterior limb of the right internal capsule. Put simply, a blood clot in the right-hand base of my brain. Had the clot affected the left side, I probably wouldn’t be writing any story.

It happened in the early hours of 10 September 2024. Rarely for me, I needed the loo. Fortunately, that need to spend a penny probably saved my life. When I woke, I couldn’t lift a finger let alone my left leg or arm. A bizarre, bemusing, increasingly alarming and scary experience. Had I slept on a nerve? Had I heck. After a minute or two, I was pretty sure whatever had happened – was still happening – was serious. I suspected a stroke but it would be hours before this was confirmed.

Curiously, a sense of calm took over as a chain of events took off starting with a phone call leading to the arrival of paramedics. This was followed by a lengthy ambulance wait outside A&E, endless questions and a battery of checks, tests and scans that eventually culminated in my admission to the acute stroke unit.

Back then, I knew next to nothing about the condition. I’ve since spent a year in recovery amassing knowledge and first-hand experience; undergoing months of physiotherapy and picking up some of the reins of my former existence. It was – and still is – the steepest learning curve of my life.

Around 100,000 people a year in the UK have a stroke: that’s roughly equivalent to a stroke every five minutes. It’s the main cause of acquired disability in the UK and the fourth single leading cause of death. Clearly, thank god, it’s not always fatal: currently 1.4million people in the UK are living with the effects of a stroke. Every stroke is unique, every sufferer’s experience, different. Severity and effects vary wildly.

During the nineteen days I spent in hospital, three different doctors told me I’d had a mild stroke. I guess it depends on your definition. Mild is not a description I’d use. I soon stopped using the term stroke completely. It’s far too benign; a word that conjures cute images, casual sayings throwaway remarks: we stroke kittens, wait for the stroke of midnight, sign deals at the stroke of a pen. As for a stroke of luck . . . give me a break.

I call a stroke what it is: a brain attack. Think cardiac arrest but in the brain. I visualised a malign scarlet clot in full military fatigues, hacking through blood vessels with a machete, squatting malevolently in neural pathways. In a bid to wipe the smile off its smug little face, I called it Brian. (I’m a writer. I have a vivid imagination.) The aim was to cut the bloody thing down to size and maintain a sense of humour however dark. Initially, I was the one felled and, thanks to Brian, laughs were in short supply.

But not for long. Crying did nobody any good; negative thoughts led to places I didn’t want to go. I was alive if not kicking and lucky to the extent my cognitive skills, speech and senses were unaffected. Meaning, to coin a phrase, I could ‘always look on the bright side’ and I still had – to use the vernacular – the gift of the gab. This linguistic ability was, I have no doubt, instrumental in doctors letting me leave hospital under the Early Discharge Scheme. It took a good deal of silver-tongued persuasion.

Although after eleven days I’d been pronounced medically sound, I could still barely walk, wash or feed myself. I was receiving tremendous care and encouragement from nurses and physios but I was enduring virtually sleepless nights. I was beset by constant lights, the hum and clicks of machinery, the screams and shouts of other patients’ pain, distress and confusion.

Perpetual exhaustion wasn’t just affecting me emotionally and psychologically, I knew it was having a detrimental impact on my physical recovery. It took three lengthy and impassioned pleas before I managed to convince my consultant that I’d be better off in every way at home where I’d not only be able to get essential peace and quiet to rest but would have exceptional care from my husband. I’ll be forever grateful to my consultant for actually listening and respecting my views. Once I’d passed a few more tests and tasks, I was free to leave.

The homecoming was emotional. I cried tears of joy laced with relief. I was convinced that by Christmas I’d be back to my old self: alive and kicking, out and about, up and running. After all, I’d had a mild stroke, hadn’t I? I reckoned three months’ recovery would fix it. I’d wake up one morning throw off the bedcovers and that’d be it – I’d have my old life back; I’d be as good as new. I genuinely cannot believe how naïve I was.

Coming next: From Great Expectations to Hard Times

July 19, 2021

YOU’VE COME A LONG WAY, BABY

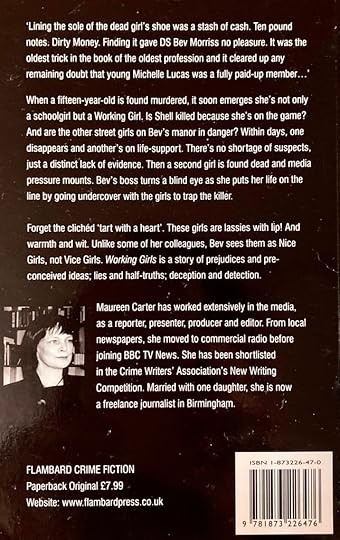

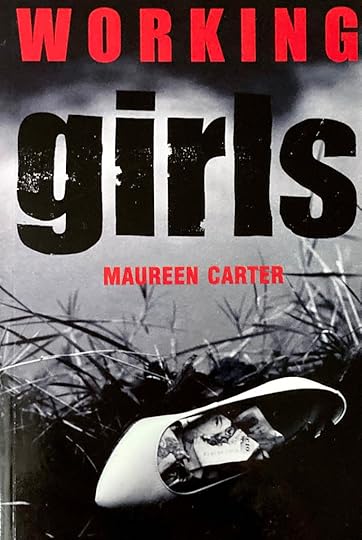

Writing’s often described as a labour of love and, I’ve heard said, completing a novel’s like giving birth, in which case (bear with me while I run with this analogy) this year my firstborn is celebrating quite a milestone. My first published novel is twenty years old. Happy birthday, Working Girls.

Here’s a pic from its launch party and why ‘Girls’ holds a very special place in my heart . . .

The book entered the publishing world way back in September 2001 yet even now I can recall my author copies arriving as though they’d been delivered this morning. That almost indescribable moment, a series of exquisite ‘firsts’: turning the book in my hands, leafing through the pages, seeing my carefully-crafted prose in print, the cover carrying my name, the scent of the ink. I know I had the broadest smile on my face even as tears welled in my eyes.

But then I’d waited eight seemingly long years for what at times had appeared the impossible, the unattainable. The publication of Working Girls validated all the hours of hard graft during which I’d written four crime novels, countless short stories, submitted scripts on numerous occasions; garnered a host of rave rejections but no contract. Close but no cigar, as they say. High hopes, dashed expectations.

I’d reluctantly decided Working Girls would be my last shot, my final attempt at realising an ambition I’d held for as long as I could remember – to be a published author. I’d worked with words throughout my career, first as a newspaper reporter then in radio and finally as journalist, presenter and producer with BBC TV news.

I loved my time in journalism but after more than twenty years, I was ready for a new challenge. Even as a child I’d dreamt of becoming an author and as time passed knew I wanted to write crime fiction. I wanted to create books that people would want to read, characters they’d fall in love with.

And for that I needed a distinctive lead detective . . .

Back then, with honourable exceptions, the genre featured a lot of middle-aged male cops, often angst-ridden mavericks with dubious tastes in music, an idiosyncratic mode of transport and an endless capacity for alcohol.

Pointy elbow

Don’t get me wrong, I read those books with relish, positively lapped them up. Indeed, initially, I envisaged a similar sort of senior officer for Working Girls. But I hadn’t bargained on Detective Sergeant Beverley Morriss barging her way onto the screen, all pointy-elbow, sharp-tongue and kick-ass attitude.

More than all this though – and one of the reasons readers took her to their hearts – Bev cared about the people she met, the victims, grieving relatives, the under-privileged, anyone who’d been dealt a bum hand in the game of life.

And so the stroppy sergeant gradually but inexorably took centre stage from the man I had in mind to play her boss. As the song says, you’ve come a long way baby. Not unlike the book.

Original cover from Flambard Press

Original cover from Flambard Press

Second issue by Creme de la Crime

Second issue by Creme de la Crime

Creative Content’s rebrand

Creative Content’s rebrandI can barely believe it’s two decades since Bev took those first steps shadowing working girls as they sashayed onto Birmingham’s mean streets and back alleys. Along the way, she’s covered a lot of ground: there are now ten titles in the series, and Bev leads the action in every one.

Described as feisty before the word became a cliché, she’s outspoken, obstinate and frequently obstreperous but she loves her mum, loathes the bad guys and has a penchant for Sauvignon Blanc.

As Sharon Wheeler, Reviewing the Evidence, put it:

Many writers would sell their firstborn to have the ability to create such a distinctive ‘voice’ in a main character.

Thank you, Sharon.

Talking of voices, so to speak, I can’t tell you how thrilled I was when, nine years after its release, Working Girls was brought out in audio. Published and produced by the crack team at my publishers Creative Content, it was narrated by one of my favourite actors: the peerless Frances Barber. Listening to Frances give voice to Bev and all the other characters was undoubtedly one of the highlights of my writing career. Her extraordinary performance raised the hairs on my nape and had me on the edge of the seat – and I’d written every word! Thank you, Frances.

The award-winning narrator Clare Corbett subsequently voiced most of the other books (brilliantly) and I had the pleasure of sitting in during her recording of Baby Love, the third Bev Morriss story and one of my favourites in the series. (Okay, strictly speaking I should have only one favourite but it’s like asking a mother to choose between her children!) Watching Clare in action was amazing and meeting my wonderful publishers was a delight, as you can see.

Clare Corbett

Clare Corbett

Ali Muirden, me and Lorelei King

Ali Muirden, me and Lorelei KingAnd here’s a taster . . .

Have to say that watching an audio book being recorded was certainly another of my ‘firsts’, as was being an author on a panel of debut writers at Dead on Deansgate. The panel was dubbed, New Kids on the Block, a description which in my case stretched credulity somewhat! Nonetheless it was a terrific – if terrifying – experience and I found myself seated alongside another newbie, Mark Billingham. Whatever happened to him?! Joking apart, I love Mark’s writing and he was generous enough to provide one of my later books with a great shout-line:

Crime writing and crime fighting: Maureen Carter and her creation Bev Morriss are the second city’s finest.

I’ll take that. Thank you, Mr B!

So Working Girls began my publishing journey and it’s been quite the most remarkable ride. Along the way I’ve met countless amazing people: publishers, authors, booksellers, librarians, festival organisers all of whom I thank, and my biggest thanks go to the lovely readers out there. People who’ve loved the books, fallen in (and out of) love with some of the characters, made suggestions for future plotlines and helped to spread the word. And by now I’ve written quite a few of those . . .

The ten Bev Morriss titles, published by Creative Content, are available in e-form, six are also available on audio. https://www.creativecontentdigital.com/crime_fiction.html

I’ve also written five titles in my second series featuring DI Sarah Quinn and TV journalist Caroline King. The books were originally published by Severn House and have recently been rebranded and rereleased in e-format by Joffe Books, introducing the characters to an even wider readership.

There are lots more details about me and my books here: www.maureencarter,co.uk

In the meantime, now in its twenty-first year, I raise a toast to my fictional firstborn.

Happy Birthday, Working Girls.

We’ve both come a long way, baby.

February 2, 2021

A KILLER READ, LITERALLY

Eunice Parchman killed the Coverdale family because she could not read and write

The opening line of Ruth Rendell’s A Judgement in Stone written more than forty years ago. I found it stunning then – and still do. One sentence, thirteen words. And yet the content conveys volumes. From the first word we know who the murderer is and then the name of her victims but much, much, more than that – we learn Eunice’s motive.

So ashamed of her illiteracy, Eunice took the lives of four people to stop what she saw as a shameful secret being exposed; the stigma was too great to bear.

As someone who’s read fluently from the age of four, I’d taken the ability for granted. Easy as ABC, wasn’t it? Eunice’s plight – by which I mean Baroness Rendell’s brilliant novel – made me reconsider, urged me to really think about what being illiterate means.

Difficult, isn’t it? I could barely imagine a life unable to read, of not being surrounded by books, of being cowed by the written word.

I’ve always written for a living. I love words, the way they sound, the way they look on the page or screen. I love the notion that an alphabet of just twenty-six letters is the basis for an infinite variety of lexical creations.

Fictional fantastical

Words open our eyes and our imaginations; they take us on awesome adventures, journeys to far-flung worlds – factual, fictional, fantastical; past, present and future. Along the way they introduce us to a vast array of people, places, products; issues, ideas, information.

Leaving aside the utter pleasure words give, on a purely practical level they’re vital to everyday existence. They help us find our way around, tell us the price of goods in a shop, the dishes to choose from a menu, which films are showing at the cinema. We know what’s going on in the world by reading newspapers, magazines and websites.

Poetic to prosaic

From the poetic to the purple to the prosaic – words are pretty versatile. In just one, they’re indispensable.

But not to someone who can’t read.

What if a string of letters is incomprehensible? What if it’s a struggle to make sense of the simplest sentence? What if deciphering a set of directions is beyond someone’s capability?

For someone, read 9 million people in the UK. That’s 16 per cent of adults who are functionally illiterate.

The figures are from the National Literacy Trust. The trust estimates that 5.1 million people in England have a reading age of an eleven-year-old child and that one in five adults in the UK struggles to read and write.

Some of the findings for children make equally grim reading. That’s not a play on words – there’s nothing funny about the statistics:

One in four British children struggles with basic vocabulary.383,755 children and young people in the UK don’t own a book of their own.One in five children left primary education in 2018 unable to read or write properly. (DfE)One in five.

As the NLT states, ‘This means that they will be held back at every stage of their life: as a child they won’t be able to do well at school, as a young adult they will be locked out of the job market, and on becoming a parent they won’t be able to support their child’s learning – so the cycle continues for another generation.’

Crying shame

Bear in mind the figures are before lockdowns and months of lost learning. Imagine the impact on children already lagging behind in the literacy stakes.

I find it shocking and so very sad. A crying shame. I wish I could wave a magic wand and bestow the ability to read and write on everyone immediately. That sort of thing only happens in fairy stories, but what I can do is help in a small way. I’m a reader volunteer with a national literacy charity which means I go into a local primary school and help children on a one-to-one basis to catch-up on reading skills, to help them conquer their fears and – hopefully – to foster a love of words.

I volunteer with Coram Beanstalk, but there are other literacy charities and thousands of people like me across the UK. I’d urge anyone who’s passionate about the subject to get involved.

Coram Beanstalk provides excellent training, expert guidance and big boxes of goodies: a selection of some of the best children’s books on the market.

Covid-19 restrictions have led to a temporary suspension of school sessions but when I work with a child, I can see instantly when they ‘get’ something and the word-penny drops. They lift their head, a broad smile in place, a spark in their eyes. Their joy and sense of achievement is entirely mutual and worth more than I can say.

It’s often said that a love of reading is the greatest gift you can give a child. My father gave me that gift. He died when I was eight years old but left a legacy that lasts a lifetime.

Reading matters.

Just ask Eunice.

Feeling inspired? Here’s where you can learn more:

Overview

September 10, 2018

REBEL WITH A CLAUSE

Writing rules really rile me. Nowadays it seems the world and its aunt is a literary expert, handing out gratuitous and often spurious dos and don’ts on how to write fiction, produce prose and create characters. I even came across a tweet the other day giving tips on naming characters. Strikes me if you want to be a writer and need that much help, maybe stick to the day job.

It’s not just unsolicited guidance that irks me, I find rigid grammar rules annoying as well. I’m rigorous about correct spelling and punctuation, but splitting the odd infinitive? Ending a sentence with a preposition? Beginning a sentence with a conjunction? They’re all fine in my book(s).

Errant

Unlike misspelt words, missing apostrophes and misplaced commas – split infinitives don’t change what a writer’s trying to convey, neither does a sentence that ends with a preposition. In fact sticking to the preposition rule can sound preposterous. As Winston Churchill pointed out when admonished for breaking the rule: ‘This is the type of errant pedantry up with which I will not put.’ Nor do I.

And as for not starting a sentence with a conjunction. And not writing incomplete sentences.

Or one-line paragraphs.

Or eschewing contractions.

It is daft, is it not?

But back to all the gratuitous writing advice that flows on Twitter and Facebook et al, my main gripe with the literary largess is that it assumes what works for one writer will work for all writers. The way I see it, the one-size fits all approach is not only patently wrong but – like Lassa fever – it’s something to avoid.

The whole point of writing fiction is, surely, to create a unique authorial voice, not slavishly follow other people’s well-worn blueprints of general and often inherited advice.

I get particularly tetchy when a rule starts with the word ‘never’ – as in, never do this, never do that. I’m thinking of instances like: never open a book with the weather or, never start with a prologue. Avoid overuse, sure. But, never? Personally, I think it’s a tad presumptuous on anyone’s part to lay down the literary law like that.

Seamless

Another bugbear of mine is, show don’t tell. The term’s blithely bestowed on all beginner writers but when you think about it, it’s pretty meaningless. There are times an author has to spell it out or risk confusing the reader or failing to convey essential information. I’m talking here about weaving a little seamless clarification into a scene, not spoon feeding huge chunks of exposition and/or explanation.

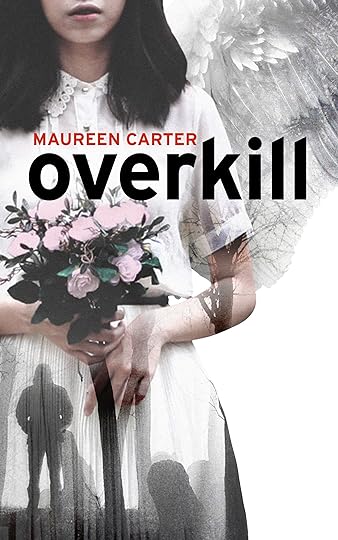

And then there’s the old chestnut: write about what you know. I’d be nuts to stick to that little pearl of wisdom. In my books, I kill people for a living. My villains range from murderers to kidnappers; blackmailers to serial burglars. My plots have featured prostitution and paedophilia. My latest novel – Overkill – looks at rival pimps. You get the picture. And that’s what I do – picture action sequences and create characters in my head. It’s called imagination.

Of course I also use my experience and expertise as a former TV journalist. The media features heavily in my novels but as a crime author my mantra is: write what you can find out about. And that means doing extensive research and owning a burgeoning book of contacts. Mine’s mainly full of police officers, lawyers and medicos. I talk to them when I need expert knowledge to add authenticity to my work. (I say ‘talk’, it’s more a case of badgering them with questions.)

I have other pet hates in the field of unasked for tips and unwarranted advice, but you may feel differently. Maybe you find them helpful. I’d love to hear your thoughts. Each to their own and all that. It’s just that I prefer making up my own rules and I’m definitely not in the market of foisting them on anyone else.

The way I see it a writer needs the confidence and self-belief to develop a distinctive writing style, to come up with original material and to craft it in the best way they can. And if that means breaking the rules . . . bring it on.

For me it’s about engaging the reader with an engrossing plot and entertaining characters. And for that, I keep in mind the three Cs: communicate, clarify, connect.

Carter’s rules. But not for general consumption!