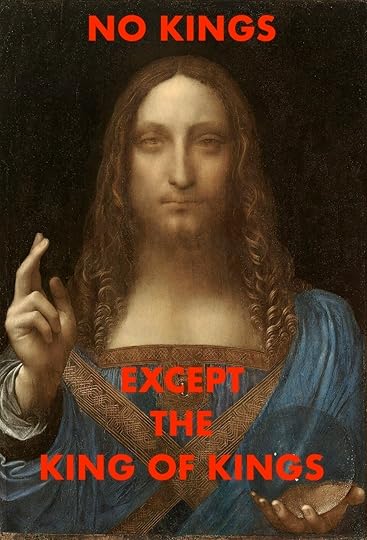

should Christians be anarchists?

I wrote in my anarchist notebook:

Jacques Ellul thinks that Christians should be anarchists because God, in Jesus Christ, has renounced Lordship. I think something almost the opposite: it is because Jesus is Lord (and every knee shall ultimately bow before him, and every tongue confess his Lordship) that Christians should be anarchists.

I hadn’t remembered writing that, but came across the post this morning, just after posting on Phil Christman’s book. Do I think that Christians should be anarchists in the way that Phil thinks we should be leftists? Am I ready to grasp that nettle?

Maybe not yet, though I will say that the essential practices of anarchism — negotiation and collaboration among equals — are ones utterly neglected and desperately needed in a society in which the one and only strategy seems to be Get Management To Take My Side. And Christians are a part of that society and tend to follow that strategy.

It’s often said that the early Christians as described in the book of Acts are communists because they “hold all things in common” (2:44-45, 4:32-37). But there is a difference between (a) communism as a voluntary practice by members of a community within a much larger polity and (b) communism as the official political economy of a nation-state, backed by the state’s monopoly on force. The former is much closer to anarchism. We are not told that the Apostles ordered people to sell their possessions and lay the money at the Apostles’ feet, but rather that people chose to do so. We are told that the early Christians distributed food to the poor, but not that the Apostles ordered them to do so. The emphasis rather is on the fact that they were “of one heart and soul” (καρδία καὶ ψυχή μία).

It is commonly believed by Christians in the high-church traditions, like mine, that the threefold order of ministry (bishop, priest, deacon) mandates a hierarchical structure of decision-making, but I am not sure that’s true. Things did indeed develop along those lines, but that’s because — this is an old theme of mine — church leaders saw the administrative structure of the Roman state as something to imitate rather than something to defy. A diocese was originally a Roman administrative unit; nothing in the New Testament even hints that an episkopos is anything like the Roman prefect (praefectus praetorio) or a priest like his representative (vicarius). The office developed along Roman/political lines, but it needn’t have developed that way.

And indeed, in some traditions — for instance, American Anglicanism — it’s possible to discern the lineaments of a somewhat different model: when the rector is charged with the spiritual care of the parish and the vestry are charged with the material care of the parish, there’s something of the division of labor and spheres of autonomy that we see in the better-run anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist communities. There are always tensions at the point when the spheres touch, but that’s what negotiation and voluntary collaboration are for: to resolve, or at least ease, tensions.

In these contexts I often find myself thinking of a passage from Lesslie Newbigin’s great book The Gospel in a Pluralist Society (1989):

[Roland] Allen, who served in China in the early years of this century, carried on a sustained polemic against the missionary methods of his time and contrasted them with those of St. Paul. St. Paul, he argued, never stayed in one place for more than a few months, or at most a couple of years. He did not establish what we call a “mission station,” and he certainly did not build himself a mission bungalow. On the contrary, as soon as there was an established congregation of Christian believers, he chose from among them elders, laid his hands on them, entrusted to them the care of the church, and left. By contrast, the nineteenth century missionary considered it necessary to stay, not merely for a lifetime, but for the lifetime of several generations of missionaries. Why? Because he did not think his work was done until the local church had developed a leadership which had mastered and internalized the culture of Europe, its theological doctrines, its administrative machinery, its architecture, its music, until there was a complete replica of the “home church” equipped with everything from archdeacons to harmoniums. The young church was to be a carbon copy of the old church in England, Scotland, or Germany. In rejecting this, and in answering the question, What must have been done if the gospel is to be truly communicated? Allen answered: there must be a congregation furnished with the Bible, the sacraments, and the apostolic ministry. When these conditions are fulfilled, the missionary has done her job. The young church is then free to learn, as it goes and grows, how to embody the gospel in its own culture. [pp. 146-47]

It seems to me that this argument has implications not just for missionary activity but for every church. The model that Allen favors seems to me a way to reconcile the principle of authority with the practices of anarchism. Is it possible to have both the threefold order of ministry and a congregational life that’s based on the one-heart-one-soul way of life?

I want to mull that question over for a while and return to it later. I feel confident that Christians should incorporate more of the foundational anarchistic practices into their common life, but does that mean that Christians should be anarchists? Hmmmm.

newest »

newest »

I would recommend The Celtic Way of Evangelism, Tenth Anniversary Edition: How Christianity Can Reach the West . . .Again. Study of Patrick's method of evangelism, which did not try to Romanize his converts.

I would recommend The Celtic Way of Evangelism, Tenth Anniversary Edition: How Christianity Can Reach the West . . .Again. Study of Patrick's method of evangelism, which did not try to Romanize his converts.

Alan Jacobs's Blog

- Alan Jacobs's profile

- 531 followers