The Crash of '87...and Maybe the Next One

Worries about another stock market crash keep ratcheting higher. Back in 1987, I had a close-up view of a previous crash. If and when there’s a next one, in many ways it won’t look like 1987, and in many ways it no doubt will.

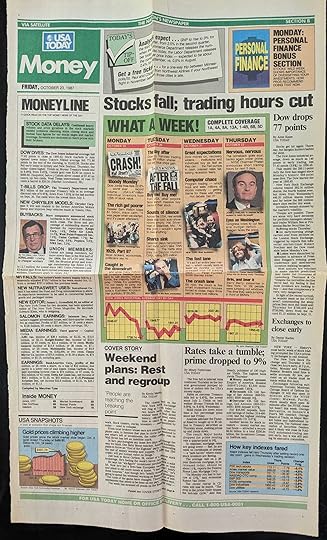

Well, here’s one way it won’t be the same. I wrote this in a story that appeared on Friday, October 23, 1987 – the end of a wild week that started with a market meltdown that Monday.

Making its rounds is the Billy Martin Theory: that every time Martin gets rehired to manage the New York Yankees baseball team, the market drops. He was hired for the fifth time on Monday.

Billy Martin died in 1989.

Anyway, here’s some backstory: In the fall of 1987 I had been a journalist in the Money section at USA Today for a little more than two years. When the biggest business story of the year exploded – that would be the crash on Monday, October 19 – I got put in the hot seat.

On that Monday, I wrote Tuesday’s page one story about the crash. On Wednesday, I contributed to Thursday’s cover story about Wall Street’s tentative rebound. And then on Thursday I wrote another cover story for Friday’s paper, headlined “WHAT A WEEK! Weekend plans: Rest and regroup.”

Me and the ‘87 crash – we got intimate.

One thing that’s always true about market crashes: lots of people worry that one is coming, and then everybody is surprised when it arrives.

From lots that I’ve read about it, that seems to have been true in 1929. It was true in 1987. The same in 2000 and 2008. Can’t imagine it won’t be true next time. The opening line of my Tuesday story: Doom swallowed Wall Street Monday. Bad news was expected, but the crash reached a scale nobody could have imagined.

Stocks had been ablaze in the mid-1980s. Remember yuppies? Short for “young upwardly-mobile professionals”? In the ‘80s they were early-career Baby Boomers suddenly making a lot of money and indulging in “power suits,” BMWs, IBM PCs…and stocks.

Money was pouring into stocks and mutual funds. Wall Street was the red-hot center of American culture. Hollywood made the iconic movie Wall Street, starring Michael Douglas and a pre-nutty Charlie Sheen, in which Douglas’ character famously evangelized why “Greed is good.” (And then the movie came out in December 1987, after the real Wall Street crumbled.)

About a month before the ‘87 crash, markets had started stalling. Interest rates and inflation were heading higher – both usually bad news for stocks. Investor confidence was wavering. But most investors stayed in, telling themselves that the moment would pass and the economy was strong and markets would continue to march higher.

By the time I got to work on that Monday, panic was already in the air. Stocks were diving. Anticipating trouble, New York closed Wall Street to traffic. People started crowding the street in front of the New York Stock Exchange. I never could figure out what they thought they’d see. A financial executive jumping off the roof?

By the end of that day, stocks fell almost 23%, wiping out about $500 billion in value – equal to $1.4 trillion today. That first-day story was mostly about market statistics and chaos – the crazy day that brokers and investors experienced. I was collecting information and writing as the crash was happening. One of my colleagues went to Wall Street and filed some on-the-scene details for the story. My favorite:

But doing well were drug dealers who plied their trade on Pine Street, two blocks from the nondescript marble stock exchange building. Men in three-piece suits were buying $25 bags of marijuana at a brisk clip. “I’m doing a great deal more than usual,” said a dealer who wouldn’t give his name. He said he hoped to do $1,000 Monday.

See, that shows a way a new crash won’t be like the ‘87 crash. There are now about a half-dozen dispensaries within a 15-minute walk of Wall Street. Bummed-out traders can get stoned legitimately.

Then the Thursday story read like a sigh of relief. On that Tuesday and Wednesday stocks regained about half their losses. Aggressive investors had figured that stocks had fallen so far, they were on sale. Thomas Czech, a markets analyst at since-defunct Blunt Ellis & Loewi in Minneapolis, told us: “We see a large increase in greed here. We’re seeing people throwing money fast and hard and maybe without thinking.”

The misplaced optimism, of course, reversed itself and led to stocks diving again on Thursday. On Friday, with brokers, traders and officials exhausted and overwhelmed, the NYSE closed two hours early.

And that’s another way a crash today would be different. Isn’t all the trading now by computer? Are any humans even on the NYSE floor? Who’s there to get exhausted?

Oh, another difference vs. 1987: Now you can go online and watch your stocks plummet in real time. This was in my Friday story:

The Associated Press’ stock tables – the only stock figures for millions of investors – have wheezed all week. Closing prices often didn’t make it into member newspapers.

A lot of people didn’t know how badly they got hit for days.

Finally, there is another commonality to all market crashes: In its aftermath, much of the public is glad to see some full-of-themselves richy-rich class get their ass kicked. I wrote:

Psychologists popped up everywhere saying that the money-grubbing Y-word class has finally learned its lesson. “There’s a great deal of glee out there that greed has finally caught up with these people,” says Linda Barbanel, a New York psychotherapist who calls herself the Dr. Ruth of money.

Here in 2025, it’s the AI bros who are most at risk for a comeuppance.

I can tell you one thing they must avoid at all costs: building an AI Billy Martin and tempting the Yankees to hire it as manager.

–

These are the pages and stories from Tuesday, October 20, 1987, and Friday, October 23, 1987.