Kevin Maney's Blog

January 28, 2026

Why AI Will Kill Your Job So You Can Make a Better One

I believe that the existential worries about AI putting us all out of work are misguided, but the reasons are different from what almost everyone seems to be talking about.

It starts with this: People want to work. Sure, some don’t, but most do, and that applies even if the gung-ho AI fanboys are right when they say AI will create some kind of utopian abundance and spin off so much wealth that we’ll all get a sizable monthly AI dividend.

Most people would still want to do something constructive, and a lot of people would still want to make money, even if they get a dividend. Just look at scions of super-rich people. They don’t have to do anything but play, yet most of them choose to do something at least somewhat purposeful. (David Ellison certainly doesn’t NEED to try to run the world’s biggest media company…)

So if AI starts booting huge numbers of people out of the kinds of jobs they’d been doing, that means AI would be creating a gigantic, important, urgent problem for huge numbers of people. It’s both a personal and societal problem: How can people do meaningful, remunerative work in the post-AI era?

In a long career of writing about the tech industry and a decade of working with companies on category creation and design, one thing that’s become super clear to me is that gigantic, important problems are magnets for entrepreneurs and investors. New categories of products and services are born when someone sets out to solve a problem.

The bigger the problem, the more valuable the category and the companies in it. Both the challenge and the potential wealth creation are the major attractions.

Now, my business partner, Mike Damphousse, and I have a new book coming out based on our work, titled The Category Creation Formula. This is relevant to the AI and jobs problem. The “formula” is simply: context + missing + innovation = a new category. As a way to help a company’s leaders see, frame and build a new category, the formula as a discussion driver works every time.

Briefly, context is what’s going on in the world, which includes new technologies, shifts in geopolitics, economic conditions, changes in societal mores, etc. The missing is an unsolved problem in that new context – maybe it’s a new problem, or maybe it’s an aching old problem that now can be solved because of the context shift. Finally, the innovation is the solution to the problem. Create that innovation, and you’re creating a new category of product or service that the world needs and the market will vacuum up.

The bigger the context shift, the bigger the new problems that need solving. And the bigger the problem, the more powerful the magnet compelling entrepreneurs and investors to it. If AI puts hundreds of millions or billions of people out of traditional work – that’s about as big a problem as you’re gonna get.

The usual optimistic counter-argument to “AI will kill all the jobs” is that new technologies always make some kinds of work obsolete, but create entirely new kinds of work. And, yes, this has been true. My grandfather was an ice deliveryman in the era of ice boxes in homes. Electric-powered refrigerators killed that job in the 1930s. But then electricity opened up a new career for him, as an electrician. If my grandfather were around today, he’d be astounded that anyone could have a job doing something called “search engine optimization,” entirely created by 2000s-era technology. Career paths have always constantly morphed, and generally technology has made work better and more abundant for society as a whole.

Besides, if new tech always killed off old jobs but didn’t create new ones, by now we’d all be living the life of a house cat.

The Elon Musks and Sam Altmans say that this time it’s different. AI is going to become so powerful so fast, it will be like a tsunami wiping out much of what people now do for work. Whatever new jobs it creates will be done by AI or robots! We’ll be left on the sidelines.

And, yeah, it can be hard right now to foresee all the many wonderful new jobs for humans that AI will create. So, what could possibly save us?

But…people want to work, and having billions of jobs killed by AI is a problem many ambitious people will want to solve – for society or for themselves. I believe we’re seeing the beginnings of how that will play out.

Early this year, Anish Acharya, a partner at Andreessen Horowitz, published a newsletter titled “Software’s YouTube Moment is Happening Now.” He pointed out that before YouTube (and other enablers that arrived around the same time, like cameras on phones and video editing software), video media was the province of professionals. Everyday people didn’t have the equipment or specialized knowledge to produce a show, movie or music video, and even if they did they didn’t have a way to put their work in front of millions of people. A relatively small number of people had careers in television or movies.

Technology changed that. Fast-forward to recent years, and YouTube reaches an audience of billions for free, and then there’s also Instagram and TikTok and other platforms. Great phone cameras are ubiquitous; editing tools are free and simple. What used to be costly, hard and took professional training today is open to almost anyone with an idea. There are now an estimated 27 million paid content creators in the U.S. alone. That’s 27 million jobs that didn’t exist before – jobs that no one in, say, 1990 could’ve imagined.

Acharya argued that code-writing AI, like Claude Code, is ushering in a YouTube moment for software creation. “If you’ve never programmed, you can type into a text box and see what happens,” he wrote. “Today, anyone can ship an app.”

In January Steven Strauss, a professor at Princeton and Harvard, made a similar point based on his direct observations: “Last summer, student teams of mostly non-coders – marketing professionals, operations managers – built minimum viable products in days. Not mockups. Working software. Following a vibe coding workshop, students in my Harvard Summer School course accomplished things that would have been unthinkable two years earlier.”

The ramification of what both Strauss and Acharya are saying is enormous. Over the past couple of decades, technology has turned content creation into millions of jobs. Software creation is even more powerful. Software does things other people need to have done. It can be a business. AI is making it easy and inexpensive to build software products. AI will turn business creation into something that millions of people – people who never had a path to building a tech business – can do.

“If you run an incubator, teach entrepreneurship or management, or make early-stage investment decisions, the research consensus is now clear enough to act on: The economics of launching a venture have fundamentally changed,” Strauss wrote.

“Software is becoming a viral medium, and soon no one will have any excuses not to make it,” Acharya concluded. “There’s a lot of angst about ‘the kids’ these days. I have no angst, but maybe a little envy. AI has massively democratized leverage and productivity for creative people. There has never been a better time to be a young person with great ideas.”

However, there’s still a huge problem to solve. To stick with the YouTubification analogy, Claude Code and its ilk are more like the phone cameras and easy editing tools of a decade or two back. They made it easy for anyone to create video content. Coding AI makes it easy for anyone to create a software business.

What’s missing for software and software businesses is a software version of YouTube. YouTube gave creators a way to distribute what they created to the masses, and eventually gave them a way to make money on what they created. Other distribution platforms followed – Instagram, TikTok, and similar platforms around the world.

Today, an open, free, easy-to-use online mall of individually-built software businesses would probably be a great unlock for new-era jobs for millions. That seems like one huge category-creation opportunity that I’m betting many founders will chase.

What will that innovation be like? Too hard to know. Soon after YouTube was founded in 2005, I was at a tech conference where two of YouTube’s founders, Steve Chen and Chad Hurley, showed off a service that at the time was meant to let people upload home videos so friends and family could see them. That by itself seemed miraculous. No one in that room foresaw it would become a $50 billion business and one of the world’s most powerful media outlets. Anyone who thinks they know how a user-generated software business platform will evolve over the coming years is just guessing.

People want to work. AI might make your job obsolete, or make it harder to get hired because AI can help one person do the job of ten. A company that used to employ 300 might only need 30. But a lot of people who can’t find a way to do what they used to do will have a path and motivation to start and run their own one-person or five-person company.

Multiply that over and over and we could end up with a different kind of economy – one where big companies and big company jobs get more rare while there’s an explosion of very small and profitable companies. (Which, by the way, could be based anywhere.) The nature of those AI-enabled companies and jobs will be as foreign to us as a search engine optimizer or Instagram influencer would’ve been to my ice-delivering grandfather.

In 2018, Hemant Taneja and I published a book titled Unscaled, based on our theory that twenty-first century technology – AI in particular – is going to take apart the scaled-up, mass-market, mass-production industries that were built in the twentieth century. Giant companies that sought to make the same product for the most people would give way to millions of small entities that profitably make exactly what narrow niche markets desire. I think the Youtubification of software is an accelerant for that trend.

Is AI going to blow up a lot of careers? No doubt. Will it create new kinds of great jobs for humans – jobs humans do because AI can’t? Very likely, just as electricity killed off ice delivery but made way for an electrician who could wire up a house for a refrigerator.

But the more exciting probability is that AI will give us humans a kind of agency we never could have envisioned. AI will give humans a way to dream up and create their own jobs, their own new kinds of work, and their own now-unimaginable careers.

People want to work. I believe they will.

—

This story ran in the Binghamton Press on December 16, 1937. The man on the left is my grandfather. Also, he liked highballs.

December 28, 2025

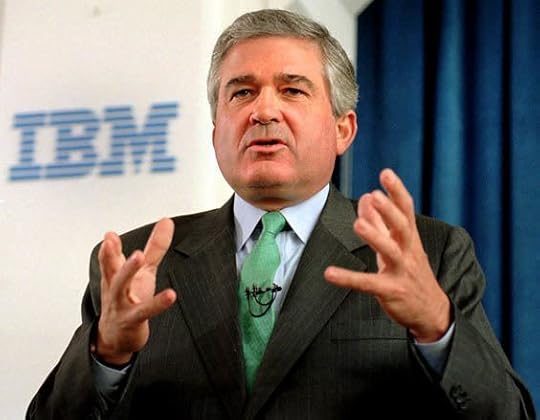

Lou Gerstner's First Day at IBM

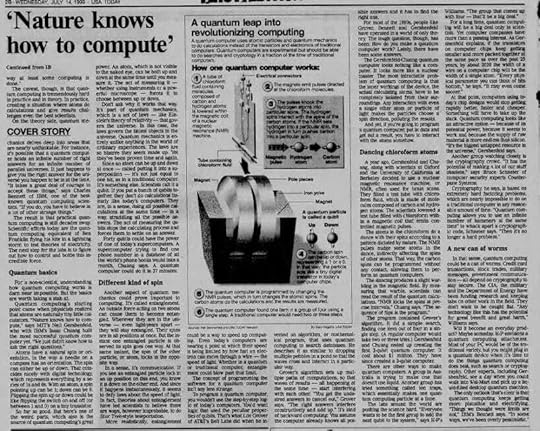

Now that Lou Gerstner has died, you may read lots of stories about how he rescued IBM – which was certainly one of history’s great feats of management. But I have a fun little Gerstner story that I doubt you’ll see anywhere else today.

I’ve written about IBM my entire career. When Gerstner took over as IBM’s chief executive in 1993, I wrote USA Today’s cover story. I talked to him many times after that.

In 2002, after I had been working for a couple of years on what would be my biography of Thomas Watson Sr., who built and ran IBM from 1914 to the 1950s, I met Gerstner in his office at IBM headquarters in Armonk, N.Y. He seemed sunnier than usual. (Around the media, Gerstner had never been particularly sunny.) He told me he was about to announce he was retiring.

Then he told a story about his first day as IBM’s CEO.

I used that story when I wrote the script for a 2018 Wondery podcast series titled “The First Computer War.” Below is that part of the script. I dramatized the story for the podcast, but all of it is true, as told to me by Gerstner. (Gerstner also tells a brief version of the story in his book, Who Says Elephants Can’t Dance, and I wrote a version in my Watson biography, The Maverick and His Machine.)

The italicized parts are dialogue.

–

It is a bright spring day in 1993. We’re in the toniest part of Greenwich, Conn. – where sprawling houses by the water bump up against a marina packed with sailboats swaying with the waves. Louis Gerstner, short, balding, ruggedly built and dressed in a beautiful tailored suit, steps out of his house and toward a black luxury car waiting in his driveway to take him to work in New York City 30 miles to the south.

Gerstner is just starting as the new CEO of IBM. Before this, he was CEO of a food and tobacco company, RJR Nabisco. IBM’s board recruited him to turn the company around.

Gerstner opens the back door of the car, slides in, and jumps back, startled to see someone already sitting on the other side of the seat. He does a double-take, and realizes his passenger is Thomas Watson Jr.

Watson:

Mind if I ride to work with you?

In one of the odder twists in business history, Gerstner lives next door to Watson and his wife, Olive. It’s been 15 years since Watson retired as IBM’s CEO – a job his father held for 40 years before that. Gerstner and Watson don’t know each other well, and their proximity has nothing to do with Gerstner getting the IBM job.

Watson wants to rant.

Watson:

Lou, I am mad as hell about what they have done to my company! Those people don’t know what the hell they are doing. I want you to tear the place up and move quickly. We took bold action in my day. I’m not going to tell you what to do, but I will tell you that it better be bold.

Gerstner has a sense of humor and a preternatural calm about him. He looks at the angry Watson and smiles, saying:

Gerstner:

You know, I’m sitting here thinking, this is a really special moment.

Watson can’t help but laugh. But on the ride, the two feel that something important is happening. Gerstner senses that Watson is handing him the keys to the Watson culture that once made IBM great.

The moment lingers with Gerstner as he gets to IBM’s New York offices and meets for the first time with the executives who will report to him. They gather around a long wooden boardroom table. They stare at Gerstner anxiously, waiting to be told that they’re all fired, or that IBM will be broken up and sold, or some other horror.

Instead, Gerstner says he wants to keep the company together.

Gerstner:

We’re under tremendous pressure – from the media, from Wall Street. We’re not going to be given a lot of time. The first thing we have to do is shore up the balance sheet. And we’re going to have layoffs.

There is a gasp in the room. Through its 80-year history to this point, IBM has never laid off workers. Not even in the Great Depression.

Gerstner:

I know there are a lot of things at this company that have become sacred. Some of those things are sacred because they are powerful parts of IBM’s culture, and we’re not going to mess with those. But some of those things are sacred for the wrong reasons, and I’m not going to hesitate to kick those out the door. Our job is to find IBM’s core, protect it, and change everything else.

The meeting is exhausting. It’s a tiny taste of how much Gerstner is going to have to do to stabilize IBM, and then help the company rediscover its own greatness.

After a long day of more such meetings, Gerstner gets back in his car, and the driver takes him to the airport. IBM’s corporate jet is waiting to take Gerstner to yet more meetings – this time with IBM customers. He’s expecting the customers to beat him up over IBM’s failings over the past decade.

Finally, on the jet, Gerstner settles into one of the leather captain’s chairs and relaxes. He is the only one on board. He calls the stewardess over to him.

Gerstner:

You know, after a day like I’ve had, I could really use a drink. What do we have on board?

Stewardess:

Um, well, sir, there is no alcohol on IBM airplanes. It is prohibited to serve alcohol.

Way back in IBM’s past, the company’s patriarch, Thomas Watson Sr., did not drink and disapproved of drinking. So for 80 years, alcohol was banned from official IBM life. Gerstner thinks: That is clearly one of those sacred things that needs to be kicked out the door.

Gerstner (wryly):

Can you think of anyone who could change that rule?

Stewardess:

Well, perhaps you could, sir.

Gerstner:

It’s changed, effective immediately.

—

Here is the story I wrote for USA Today when Gerstner was hired as IBM’s CEO:

December 19, 2025

What iRobot Taught Us About Home Robots

What’s more likely to service your home in the not-so-far future: a do-everything housekeeper robot like Rosie from The Jetsons, or a swarm of specialized bots that are more like Mrs. Potts and her household of anthropomorphized appliances in Disney’s The Beauty and the Beast?

This is the question that iRobot’s Roomba posed back in the early 2000s. Seems like it’s still to be answered even as iRobot recently declared bankruptcy.

I first met a Roomba robot vacuum cleaner in January of 2003, just a few months after it had been introduced by iRobot. I interviewed iRobot’s CEO and co-founder, Colin Angle, and the company sent me one of those first Roombas to try out at my house.

From the start, I thought the most interesting thing about the Roomba wasn’t the device itself, but the vision it teed up for how robots will infiltrate our lives. TV and movies liked to imagine robots as mechanical humanoids: Rosie on The Jetsons, C-3PO in Star Wars, The Iron Giant, Ex Machina. Lots of companies and labs are chasing this concept today.

But a walking, talking, do-everything robot is a highly complex technological lift. So far, we’ve mostly gotten Russian robots that fall on their faces on stage and soccer robots that couldn’t beat a team of blotto drunk 100-year-old nursing home residents.

Maybe it’s misguided to try to get robots to be like a human, versus getting robots to just be robots and do repetitive boring crap that robots can do really well.

The founding iRobot team, all out of MIT’s Artificial Intelligence Lab, came to that kind of thinking the hard way. The company was founded in 1990, a dozen years before the Roomba. As Angle told me in 2003, iRobot first tried to build more complex robots, like one that could seek out and explode underwater mines, and an AI-driven pet ball that would do things like cry if left alone in a dark place. None of it caught on.

But, Angle said, when he’d casually chat with someone and say he runs a robotics company, they’d often half joke that he should make a bot that would clean their floors. And then iRobot got a contract from S.C. Johnson – maker of Pledge, Windex and other cleaning products – to build an industrial floor-cleaning robot for, like, warehouses and factories. Put all that together, and iRobot’s team got thinking it could make an inexpensive bot that would take over a single repetitive boring duty from humans: vacuuming floors.

Once the company started down that path, “We did lots of things wrong,” Angle told me. “We got the robotic part nailed early thinking the cleaning part would be easy, then we spent 18 months making it clean.” (It actually took them longer. That first Roomba that I got did OK with dust, but couldn’t suck up a dropped piece of Cap’n Crunch.)

When the Roomba first came out, no one – including me – had seen anything like it. I described it in my column as looking “like a cross between a bathroom scale and a Belgian waffle iron.” At first it was sold in gimmicky catalogs like Sharper Image and Brookstone. The Roomba soon became a pop culture sensation. Go on YouTube, and you can find a ton of home videos of people’s cats joy-riding on Roombas. More than 1 million Roombas were sold in its first two years on the market.

If I put on my category design hat, iRobot did an amazing job of creating and dominating an entirely new category of product. It set the rules for robot vacuums, so that when competitors appeared, they all looked and operated much like Roombas. The company was in position to change our minds about home robotics. We weren’t going to come home to Rosie cooking and cleaning like a human maid – we were going to open the door to a swarm of mini-bots all doing their special thing.

Angle told me then that Roomba was going to be the first of many of these appliance bots. “My consumer group has a mission to make housework something people do by choice. We’re focused on tasks that we can accomplish robotically as good or better than the average person.” Other experts had similar outlooks. Sebastian Thrun, director of Stanford’s AI lab, in 2004 told me: “There will be robots that pick up dishes from the table and put them in the dishwasher within five years.”

It’s 20 years later, and if anyone has a robot picking up dishes, they are constantly replacing a lot of broken dishes.

I kept in touch with Angle and iRobot for a few years. I was at the iRobot booth at the Consumer Electronics Show in January 2004 when Bill Gates came by, wanting to know all about the Roomba and iRobot’s future plans. In May 2005, Roomba unveiled the Scooba, a floor mopping bot.

Angle told me then: “We aim our products at the axis of ‘hate doing it’ and ‘have to do it often.’ Mopping is near the top of people’s ‘hate doing it’ list.” He reiterated iRobot’s goal of making a suite of robots that do housework.

The company went public in November 2005. The Roomba remained a hit. By 2013, iRobot had sold more than 10 million.

And then, iRobot’s innovation seemed to stall. It introduced a window-washing bot and a gutter-cleaning bot. But they didn’t catch on, and it looks like IRobot doesn’t sell them anymore. Most housework, apparently, is really hard to automate. (The two most impactful housework automation machines – the electric dishwasher and electric clothes washer – were invented about 125 years ago. Since then…just Roomba.)

In 2022, Amazon said it would buy iRobot. Around that time, cheap robot vacuums from China started cutting into Roomba sales. Then the Amazon deal collapsed thanks to regulatory scrutiny from the European Union and the U.S. Federal Trade Commission. iRobot cut nearly one-third of its staff and Angle resigned.

This month, iRobot filed for bankruptcy and will be taken private by Shenzhen Picea Robotics, a lender and key supplier. Angle told CNBC: “This is nothing short of a tragedy for consumers, the robotics industry and America’s innovation economy.”

What about Angle’s robotic vision? It doesn’t look like he’s given up on it. He’s started a new company still in stealth mode, called Familiar Machines & Magic. He wrote on LinkedIn: “After decades in this field, I remain incurably optimistic about the future of people and robotics.” He added: “We are working to build the next generation of intelligent, teaming and purpose-first robots.”

“Teaming and purpose-first robots” is the key phrase. I really don’t see a day in any near future when I’m sitting here writing and a wise-cracking robot maid bustles around cleaning and bringing me martinis. (I don’t actually drink martinis when I write, but I like to imagine I would if a robot maid brought me one.)

More likely, I’ll be writing while one little bot vacuums, another scrubs the bathroom, one more folds and puts away laundry, and all of them terrify my cat, should I get another one.

—

This is the first column I wrote about iRobot, in January 2003, as accessed on Newspapers.com.

November 19, 2025

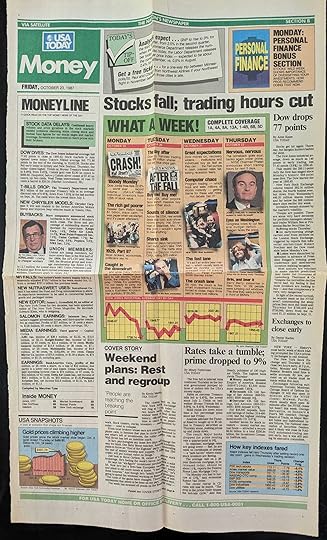

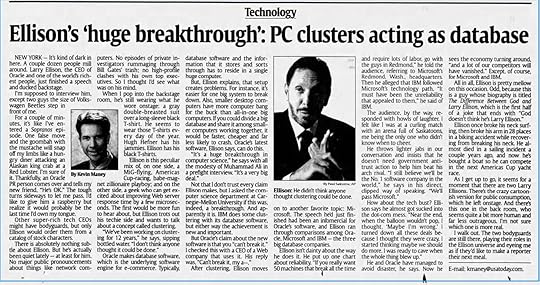

The Crash of '87...and Maybe the Next One

Worries about another stock market crash keep ratcheting higher. Back in 1987, I had a close-up view of a previous crash. If and when there’s a next one, in many ways it won’t look like 1987, and in many ways it no doubt will.

Well, here’s one way it won’t be the same. I wrote this in a story that appeared on Friday, October 23, 1987 – the end of a wild week that started with a market meltdown that Monday.

Making its rounds is the Billy Martin Theory: that every time Martin gets rehired to manage the New York Yankees baseball team, the market drops. He was hired for the fifth time on Monday.

Billy Martin died in 1989.

Anyway, here’s some backstory: In the fall of 1987 I had been a journalist in the Money section at USA Today for a little more than two years. When the biggest business story of the year exploded – that would be the crash on Monday, October 19 – I got put in the hot seat.

On that Monday, I wrote Tuesday’s page one story about the crash. On Wednesday, I contributed to Thursday’s cover story about Wall Street’s tentative rebound. And then on Thursday I wrote another cover story for Friday’s paper, headlined “WHAT A WEEK! Weekend plans: Rest and regroup.”

Me and the ‘87 crash – we got intimate.

One thing that’s always true about market crashes: lots of people worry that one is coming, and then everybody is surprised when it arrives.

From lots that I’ve read about it, that seems to have been true in 1929. It was true in 1987. The same in 2000 and 2008. Can’t imagine it won’t be true next time. The opening line of my Tuesday story: Doom swallowed Wall Street Monday. Bad news was expected, but the crash reached a scale nobody could have imagined.

Stocks had been ablaze in the mid-1980s. Remember yuppies? Short for “young upwardly-mobile professionals”? In the ‘80s they were early-career Baby Boomers suddenly making a lot of money and indulging in “power suits,” BMWs, IBM PCs…and stocks.

Money was pouring into stocks and mutual funds. Wall Street was the red-hot center of American culture. Hollywood made the iconic movie Wall Street, starring Michael Douglas and a pre-nutty Charlie Sheen, in which Douglas’ character famously evangelized why “Greed is good.” (And then the movie came out in December 1987, after the real Wall Street crumbled.)

About a month before the ‘87 crash, markets had started stalling. Interest rates and inflation were heading higher – both usually bad news for stocks. Investor confidence was wavering. But most investors stayed in, telling themselves that the moment would pass and the economy was strong and markets would continue to march higher.

By the time I got to work on that Monday, panic was already in the air. Stocks were diving. Anticipating trouble, New York closed Wall Street to traffic. People started crowding the street in front of the New York Stock Exchange. I never could figure out what they thought they’d see. A financial executive jumping off the roof?

By the end of that day, stocks fell almost 23%, wiping out about $500 billion in value – equal to $1.4 trillion today. That first-day story was mostly about market statistics and chaos – the crazy day that brokers and investors experienced. I was collecting information and writing as the crash was happening. One of my colleagues went to Wall Street and filed some on-the-scene details for the story. My favorite:

But doing well were drug dealers who plied their trade on Pine Street, two blocks from the nondescript marble stock exchange building. Men in three-piece suits were buying $25 bags of marijuana at a brisk clip. “I’m doing a great deal more than usual,” said a dealer who wouldn’t give his name. He said he hoped to do $1,000 Monday.

See, that shows a way a new crash won’t be like the ‘87 crash. There are now about a half-dozen dispensaries within a 15-minute walk of Wall Street. Bummed-out traders can get stoned legitimately.

Then the Thursday story read like a sigh of relief. On that Tuesday and Wednesday stocks regained about half their losses. Aggressive investors had figured that stocks had fallen so far, they were on sale. Thomas Czech, a markets analyst at since-defunct Blunt Ellis & Loewi in Minneapolis, told us: “We see a large increase in greed here. We’re seeing people throwing money fast and hard and maybe without thinking.”

The misplaced optimism, of course, reversed itself and led to stocks diving again on Thursday. On Friday, with brokers, traders and officials exhausted and overwhelmed, the NYSE closed two hours early.

And that’s another way a crash today would be different. Isn’t all the trading now by computer? Are any humans even on the NYSE floor? Who’s there to get exhausted?

Oh, another difference vs. 1987: Now you can go online and watch your stocks plummet in real time. This was in my Friday story:

The Associated Press’ stock tables – the only stock figures for millions of investors – have wheezed all week. Closing prices often didn’t make it into member newspapers.

A lot of people didn’t know how badly they got hit for days.

Finally, there is another commonality to all market crashes: In its aftermath, much of the public is glad to see some full-of-themselves richy-rich class get their ass kicked. I wrote:

Psychologists popped up everywhere saying that the money-grubbing Y-word class has finally learned its lesson. “There’s a great deal of glee out there that greed has finally caught up with these people,” says Linda Barbanel, a New York psychotherapist who calls herself the Dr. Ruth of money.

Here in 2025, it’s the AI bros who are most at risk for a comeuppance.

I can tell you one thing they must avoid at all costs: building an AI Billy Martin and tempting the Yankees to hire it as manager.

–

These are the pages and stories from Tuesday, October 20, 1987, and Friday, October 23, 1987.

October 18, 2025

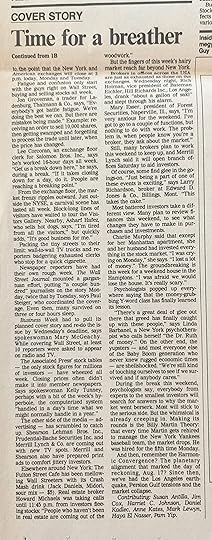

Oh, That Larry Ellison

I interviewed Oracle CEO Larry Ellison in person just once, in 2002. The main things I have long remembered about it were that the room was dark, Ellison acted like he wished I’d go away, and he had two bodyguards, each looking like they could bench press a subway car.

The details of my time with Ellison only came back to me once I re-read the story that I wrote back then. I was reminded of how odd Ellison was – and in all likelihood still is, now that he’s good buds with Trump and working with his son, David, to control a sizable chunk of American media.

Even before I met Ellison, I didn’t much admire the kind of character he was on the tech scene. The short version is that he seemed to enjoy being something of tech’s Darth Vader. He had a reputation for publicly clashing with and/or sacking his own executives, trash-talking other tech companies’ CEOs, and hiring private investigators to find dirt on Microsoft CEO Bill Gates, even having them rummage through Gates’ trash and pay off Microsoft janitors for tips. Ellison considered Gates his arch-rival and seethed at Microsoft’s success – particularly that Microsoft had more success than Oracle.

“I still believe we’ll be the number one software company in the world,” Ellison told me in that shadowed room back then. “We’ll pass Microsoft.” Hm, well, Microsoft is worth $3.8 trillion. Oracle, about $823 billion. So that didn’t happen.

Here’s how I described Ellison in my piece: “Ellison is this peculiar mix of, on one side, a MiG-flying, America’s Cup-racing, babe-magnet zillionaire playboy; and on the other side, a geek who can get excited about improving Web server response time by a few microseconds.”

I was disappointed, as a journalist, that I got the latter. He wanted to tell me all about software called clustering that was going to make Oracle’s databases more reliable. “It’s a huge breakthrough in computer science,” he said, and apparently it was, though for the general public that revelation was about as exciting as hearing of a new kind of automobile suspension system.

I also noted in the story: “Ellison once broke his neck surfing, then broke his arm in 28 places in a biking accident while recovering from breaking his neck. He almost died in a sailing incident a couple of years ago, and now he’s bought a boat so he can compete in the next America’s Cup yacht race.” Some people admire that kind of thing. Oracle shareholders no doubt didn’t much appreciate their CEO constantly middle-fingering death.

My interview with Ellison was arranged by his PR people, for right after he gave a speech to a tech industry group. So first I attended the speech. He used it to again poop on Microsoft.

“If you really want 50 machines that break all the time and require lots of labor, go with the guys in Redmond,” Ellison said on stage. (Just in case you don’t know, Microsoft has long been headquartered in Redmond, Wash.) Then he knocked IBM for following Microsoft’s technological path. “It must have been the unreliability that appealed to them,” Ellison said of IBM.

Once the speech was over, I was to meet Ellison backstage to talk. That’s when I encountered the bodyguards, who as soon as I walked in bolted to get between me and Ellison. They only let me pass once the PR person said, “He’s OK.” As I wrote: “For a couple of minutes, it’s like I’ve entered a Sopranos episode.”

Anyway, now it’s 23 years later. Ellison is 81, having outlasted his physical recklessness. He’s worth about $365 billion, so on one measure he’s whipped Gates, who today is worth around $105 billion. Oracle is back in the headlines because of its relationship with OpenAI and the Ellison family’s control of Paramount Skydance.

And, apparently, these days all the rich tech people have bodyguards. I didn’t realize that Ellison was ahead of the curve on that one.

“As I get up to go, it seems for a moment like there are two Larry Ellisons,” I wrote at the conclusion of my story. “There’s the crazy cartoonish version for public consumption, which he left onstage. And there’s this one in the back room, who seems quite a bit more human and far less outrageous. I’m not sure which one is more real.”

Still don’t know.

—

This is the article as it originally appeared in USA Today on February 13, 2002.

September 28, 2025

General Catalyst, Four Books, Ten Years and Lots of Billions

I first met Hemant Taneja in November of 2013. We were set up by a PR person who thought I’d find Hemant interesting, and we planned to meet at 5 pm at the bar at Café Luxembourg on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

I’m not sure what we ordered. A beer? Cocktail? We sat on barstools and I, wearing my journalist hat as tech columnist for Newsweek, likely started with small talk (Why are you in New York?) and then asked Hemant about himself and his work.

I had not before heard of Hemant. I was not familiar with his firm, General Catalyst. I knew tons of VCs and had relationships with the top firms, but General Catalyst, or GC, at the time was a lesser player. Hemant was best known for having made a major early bet on Stripe, which, in 2013, I couldn’t understand. Stripe was tiny, and it seemed to me and a whole lot of others in tech that Stripe was just another me-too payments platform, which the world wouldn’t need. (Of course, Stripe turned out to be one of the more brilliant early-stage investments. It’s now worth north of $100 billion.)

As we talked, Hemant told me about a concept that he called “unscaling.” Basically, it’s the idea that AI, the cloud, mobile devices, internet of things and other recent technologies will increasingly allow companies to do the opposite of mass-production, mass-marketing, mass-media and all the other twentieth-century “economies of scale” stuff that was designed to sell the most of the same thing to the most people.

Instead, unscaled companies will increasingly offer highly-individualized products and services that seem to be built specifically for one person. Much of that is happening today, accelerated by AI.

I’ve always been a sucker for big ideas that seem to explain something about how the world is changing, and I remember coming away from that meeting with the unscaling theory circling my brain. I started slipping the idea into Newsweek columns. I talked about unscaling some more with Hemant. The next time I was in the Bay Area, I visited him at GC’s small office there.

Sometime in 2015, after I’d written a few times about unscaling, Hemant and I met again in New York and he suggested that we should do a book together about it. I had just finished co-authoring Play Bigger, which would come out in June 2016, and was ready for a new project. We put together a proposal and sold the book idea to the publisher Public Affairs. Oddly enough, the editor who bought it was John Mahaney, who bought and edited my first book, Megamedia Shakeout, 22 years earlier.

So, Hemant and I wrote Unscaled: How AI and a New Generation of Upstarts Are Creating the Economy of the Future. It came out in 2018, apparently a good four years too early. At the time, the topic of how AI was going to upend industries across the spectrum wasn’t yet on most people’s radar. Now it’s all anyone in business talks about.

One of the chapters in Unscaled focused on healthcare. By the time the book hit the market, Hemant and General Catalyst were investing big in healthcare technologies, with a belief that AI could reinvent the sector. We decided healthcare needed a whole book of its own. Hemant brought Steve Klasko into that project. Klasko was CEO of Jefferson Health in Philadelphia, and was partnering with General Catalyst. The three of us wrote and published UnHealthcare: A Manifesto for Health Assurance.

One goal of that book was to establish a new category of healthcare that was all about using technology to keep people well and out of hospitals and doctor’s offices, and we called that category “health assurance.”

UnHealthcare came out in 2020. Almost immediately, Hemant and I started on yet another book, this time about how “responsible innovation” and how to build companies that would help (and not hurt) society. Intended Consequences was published in 2022. In tandem, Hemant set up the non-profit Responsible Innovation Labs, which helps founders build responsible-innovation companies.

Throughout all of this, Hemant was remaking General Catalyst, and he and the firm were hitting home runs with both companies it invested in and, more unusual for VCs, companies it helped start. Stripe and Samsara were big investment wins. So was Snapchat and Airbnb. Hemant co-founded Livongo, which eventually got bought for $18 billion.

In the early 2000s, GC was a regional firm based in Boston and had $257 million in assets under management (AUM). By late 2024, its AUM was $33.2 billion and GC operated nine offices globally, including in Silicon Valley, New York, London, Berlin and Mumbai. In 2025, when Time magazine ranked America’s top VC firms, General Catalyst landed at No. 2, just behind Accel and one ahead of Andreessen Horowitz.

After Intended Consequences I thought we were done writing books. But on another visit to New York, over another cocktail (this time at the Crosby Hotel Bar, in November 2022), Hemant said we should do one more – a book that would capture the core principles that guide him and his firm. I remember thinking: That seems like something a lot of people would want to read, given GC’s outsized success and Hemant’s growing fame.

At the heart of those principles would be General Catalyst’s belief that companies that benefit society and solve hard problems like climate change and the U.S. healthcare mess offer the best returns over the long haul. I loved it and signed on.

The book took about 15 months to complete. BenBella Books published it on Sept. 23. It’s titled The Transformation Principles: How to Create Enduring Change. The book details nine of these principles:

— The business must have a soul.

— Navigating ambiguity is more valuable than predicting the future.

— Creating the future beats improving the past.

— Those who play their own game win.

— Serendipity must become intentional.

— For great change, radical collaboration beats disruption.

— Context constantly changes, but human nature stays the same.

— The choice between positive impact and returns is false.

— The best results come from leading with curiosity and generosity.

Available wherever books are sold.

September 17, 2025

AI and the Pace of Change Scrambling Your Brain? Wimp!

In 1997, a lot of us felt like the world was changing at a velocity humans had never experienced. The internet was the main driver. It exploded into our lives after the release of the Mosaic browser in October 1994. Within a couple of years, the dot-com boom shattered business models and allowed us to think of new ways to do almost everything.

Compared to today, though, the pace of change in the 1990s seems like it was as slow as the comedy on “The Carol Burnett Show.” (If you haven’t watched lately, give it a try – you’ll see what I mean.) AI is upending everything. Famed Economist Tyler Cowan even co-wrote an article titled, “AI Will Change What It Is To Be Human. Are We Ready?” Sounds scary!

Well, allow me to offer a different perspective.

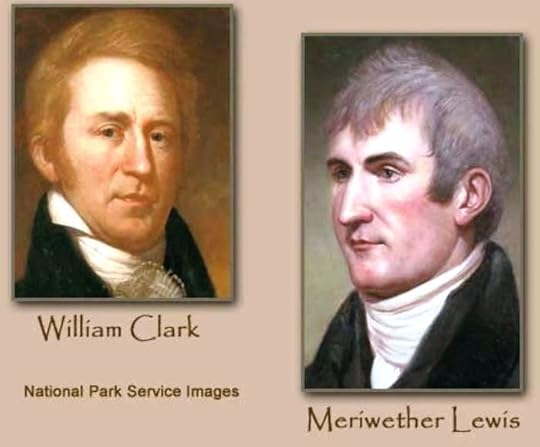

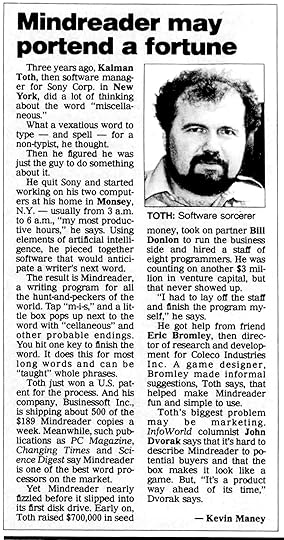

In 1996, Stephen Ambrose published his bestselling book Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. It is a detailed and gripping account of the Lewis and Clark expedition across the unmapped Western U.S. I read it soon after it first came out, and was totally fascinated.

The book made me wonder – amid the dot-com boom – what Ambrose would think of technological change and the human experience. So I called him. (As a journalist writing for USA Today, then the largest circulation newspaper in the U.S., you get to do such things.)

“Which half century experienced the most technological change since the beginning of time?” Ambrose said over the (land-line!) phone, repeating the question I’d asked him.

His answer surprised me: Nothing compares to the early 19th century – which was the time of Lewis and Clark, who set out from near what is now St. Louis in May 1804.

Ambrose referred me to a passage in Undaunted Courage:

Since the birth of civilization, there had been almost no changes in commerce or transportation. Technology was barely advanced over that of the Greeks. The Americans of 1801 had more gadgets, better weapons, a superior knowledge of geography and other advantages over the ancients, but they could not move goods or themselves or information by land or water any faster than had the Greeks and Romans.

As I wrote in my subsequent article about the experience of living in 1800: “Nothing could move faster than a horse. As far as people then knew, nothing ever would move faster than a horse.”

Ambrose in the book also quotes Henry Adams, who wrote in the late-1800s about conditions in Jefferson’s era: “Experience forced on men's minds the conviction that what had ever been must ever be.”

Ambrose told me: “At the beginning of the 19th century, people thought nothing was possible. By the end of the century, people thought anything was possible.”

By the mid-1800s, railroads criss-crossed the nation, carrying people and goods at 25 miles per hour. (Over long distances, a horse with a rider could at best go about 25 miles per DAY.) The telegraph, first used in 1844, moved information instantly. By late in that century, electricity powered streetcars and factories. Electric lights turned night into day.

Sure, the actual pace of change is greater right now than ever. But the nearly-unfathomable difference is that we have all lived our lives expecting change. The experience of everyone today is that technology advances and new inventions are constantly coming into our lives. Rapid change might be hard to keep up with, but it’s not alien to us.

So imagine when, generation after generation, there was little conception of progress. People learned their jobs from their parents who learned from their grandparents, and nobody expected to do those jobs differently. They had no reason to anticipate technological change. Doing so then would be like us today expecting time travel to be something we’d soon be able to book on Expedia.

We of the AI era are not as uniquely challenged as we might want to believe.

While I had Ambrose on the phone, I asked why he thought Undaunted Courage got so much attention. It sold far better than any of his other books at that point. Disney, Robert Redford and Ted Turner all called him about turning the book into a movie. (Never happened.)

“One reason, I think, is that it’s almost like science-fiction in reverse,” he told me.

When going 12 miles in a day was good. When it was a feat to tell time while traveling. When it was common for a mother to go a year without knowing any information about her son living a couple of states away. To us, understanding just how that worked is exotic.

Ambrose told me he wished he’d realized that when he wrote the book. “I’d have put more of it in there.”

Ambrose died in 2002 at 66, from lung cancer. I spoke to him only that one time.

–

Here is the column as it appeared in the Reno Gazette-Journal on Feb 3, 1997. It was distributed through Gannett News Service so ran in many papers across the U.S.

AI and the Pace of Change Scambling Your Brain? Wimp!

In 1997, a lot of us felt like the world was changing at a velocity humans had never experienced. The internet was the main driver. It exploded into our lives after the release of the Mosaic browser in October 1994. Within a couple of years, the dot-com boom shattered business models and allowed us to think of new ways to do almost everything.

Compared to today, though, the pace of change in the 1990s seems like it was as slow as the comedy on “The Carol Burnett Show.” (If you haven’t watched lately, give it a try – you’ll see what I mean.) AI is upending everything. Famed Economist Tyler Cowan even co-wrote an article titled, “AI Will Change What It Is To Be Human. Are We Ready?” Sounds scary!

Well, allow me to offer a different perspective.

In 1996, Stephen Ambrose published his bestselling book Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. It is a detailed and gripping account of the Lewis and Clark expedition across the unmapped Western U.S. I read it soon after it first came out, and was totally fascinated.

The book made me wonder – amid the dot-com boom – what Ambrose would think of technological change and the human experience. So I called him. (As a journalist writing for USA Today, then the largest circulation newspaper in the U.S., you get to do such things.)

“Which half century experienced the most technological change since the beginning of time?” Ambrose said over the (land-line!) phone, repeating the question I’d asked him.

His answer surprised me: Nothing compares to the early 19th century – which was the time of Lewis and Clark, who set out from near what is now St. Louis in May 1804.

Ambrose referred me to a passage in Undaunted Courage:

Since the birth of civilization, there had been almost no changes in commerce or transportation. Technology was barely advanced over that of the Greeks. The Americans of 1801 had more gadgets, better weapons, a superior knowledge of geography and other advantages over the ancients, but they could not move goods or themselves or information by land or water any faster than had the Greeks and Romans.

As I wrote in my subsequent article about the experience of living in 1800: “Nothing could move faster than a horse. As far as people then knew, nothing ever would move faster than a horse.”

Ambrose in the book also quotes Henry Adams, who wrote in the late-1800s about conditions in Jefferson’s era: “Experience forced on men's minds the conviction that what had ever been must ever be.”

Ambrose told me: “At the beginning of the 19th century, people thought nothing was possible. By the end of the century, people thought anything was possible.”

By the mid-1800s, railroads criss-crossed the nation, carrying people and goods at 25 miles per hour. (Over long distances, a horse with a rider could at best go about 25 miles per DAY.) The telegraph, first used in 1844, moved information instantly. By late in that century, electricity powered streetcars and factories. Electric lights turned night into day.

Sure, the actual pace of change is greater right now than ever. But the nearly-unfathomable difference is that we have all lived our lives expecting change. The experience of everyone today is that technology advances and new inventions are constantly coming into our lives. Rapid change might be hard to keep up with, but it’s not alien to us.

So imagine when, generation after generation, there was little conception of progress. People learned their jobs from their parents who learned from their grandparents, and nobody expected to do those jobs differently. They had no reason to anticipate technological change. Doing so then would be like us today expecting time travel to be something we’d soon be able to book on Expedia.

We of the AI era are not as uniquely challenged as we might want to believe.

While I had Ambrose on the phone, I asked why he thought Undaunted Courage got so much attention. It sold far better than any of his other books at that point. Disney, Robert Redford and Ted Turner all called him about turning the book into a movie. (Never happened.)

“One reason, I think, is that it’s almost like science-fiction in reverse,” he told me.

When going 12 miles in a day was good. When it was a feat to tell time while traveling. When it was common for a mother to go a year without knowing any information about her son living a couple of states away. To us, understanding just how that worked is exotic.

Ambrose told me he wished he’d realized that when he wrote the book. “I’d have put more of it in there.”

Ambrose died in 2002 at 66, from lung cancer. I spoke to him only that one time.

–

Here is the column as it appeared in the Reno Gazette-Journal on Feb 3, 1997. It was distributed through Gannett News Service so ran in many papers across the U.S.

August 18, 2025

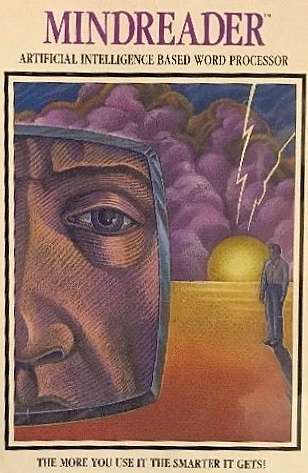

AI From 1986, Reading Minds...Badly

The first time I wrote the words “artificial intelligence” in a published article was, apparently, in 1986.

Here’s what was exciting (then!) about that 1986 AI: It was the kind of autocomplete function that we all experience today when we try to text “mortadella” and it gets changed to “mortgage.”

You know, then the text goes out as: “Hey, you good with a mortgage sandwich for lunch?”

I often use Newspapers.com to find old articles. It’s a searchable archive of more than 29,000 newspapers, some going back to the 1800s. Included are every newspaper I’ve ever written for. (I haven’t been writing since the 1800s, though sometimes it feels that way.) These days, like just about everyone else, I’m writing, thinking, and talking about AI a whole lot. So I wondered when I first encountered it as a journalist covering technology.

Turns out it was 1986, and once I saw the story, I realized it was thanks to a burly bear of a guy named Kalman Toth and his software product called Mindreader.

I vaguely remember Toth. I do remember Mindreader because he let me test it out. The software was the right idea too early. That it worked at all was miraculous. But it didn’t work well. I’m pretty sure I turned it off before long.

The Mindreader back story: Toth worked on software for Sony in its New York offices. For Lord knows what reason, he got thinking about the word “miscellaneous” and how hard it can be to spell and to type that word out. He quit Sony and started writing code to solve the miscellaneous problem.

The sentence I wrote when I first typed the words “artificial intelligence” was this: “Using elements of artificial intelligence, he pieced together software that would anticipate a writer’s next word.”

Yeah, so when you’d type “mis” it would automatically add “cellaneous.” Mind blown!

Toth started a company, Businessoft, to sell Mindreader at $189 a pop. He landed a seed investment of $700,000, but failed to get any more funding.

I don’t know much about what happened to Toth or Businessoft after I wrote about him. In 1988, another company, Brown Bag Software, released Mindreader 2.0. A site called WinWorld acknowledged that Mindreader was “originally written by Kalman Toth of BusinesSoft (sic).” You can go to that page to see what Mindreader looked like. Whoever wrote about it also concluded that the software wasn’t that useful: “The majority of its suggestions seemed irrelevant, and the auto complete does not really act as a spell checker.”

Otherwise, though, I searched all over the internet. Toth, his company and his pioneering AI seem to have vanished in the 1980s. Another software company called BusinesSoft was founded in Bulgaria in the 1990s – and still exists. It doesn’t do anything like Mindreader.

Toth is one of those too-early innovators lost to history. What he started with Mindreader has become part of our everyday lives. As I’m typing this in a Google Doc, it’s offering to complete words and sentences.

What I know now that I didn’t in 1986 is that Mindreader was a casualty of running afoul of the adjacent possible.

When my firm works with leadership teams on creating new market categories, it always involves a conversation about the adjacent possible. If you consider that there is a “possible” (all the technology that we already use) and the “not-yet-possible” (technology not yet invented or not yet very workable), then there is a border between them called the adjacent possible.

When a new technology lands in the adjacent possible, it’s new enough to be cool and amazing but mature enough to actually work well. Which is when a new technology catches on.

Mindreader was too far into the not-yet-possible. By the time more advanced versions of autocomplete entered the adjacent possible, Toth’s company had long run out of money and faded away.

(One related point: If a company is building a product that lands squarely in the possible, it’s entering an existing market and trying to scrape out a few points of market share. Those companies aren’t creating new market categories.)

Anyway, back to Mindreader. Today’s generative AI is sometimes described as superpowered autocomplete, kind of a great-great-great-grandchild of Mindreader’s technology. In fact, when I asked Anthropic’s Claude to describe how its technology works, it responded:

Think of a large language model like an incredibly sophisticated autocomplete system that has read virtually everything ever written on the internet. When you type a message, it doesn't actually “understand” what you're saying in the way humans do – instead, it's making incredibly nuanced predictions about what word should come next based on the patterns it learned from analyzing billions of text examples.

Claude went on:

It's like having a friend who has memorized every conversation, book, and article ever written, and when you start a sentence, they can finish it by drawing on all those patterns – except this friend processes all that information simultaneously and can predict not just the next word, but entire coherent responses.

In other words, it’s a lot like a mindreader.

—

This is the article as it appeared in USA Today on February 13, 1986, as accessed on Newspapers.com:

June 12, 2025

Data Center In a Beer Can?

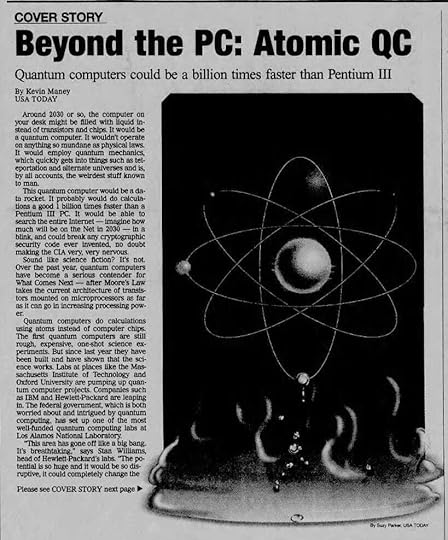

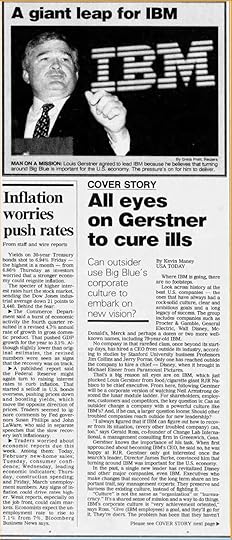

In July 1999, I opened a story for USA Today like this:

“Around 2030 or so, the computer on your desk might be filled with liquid instead of transistors or chips. It would be a quantum computer. It wouldn’t operate on anything so mundane as physical laws. It would employ quantum mechanics, which quickly gets into things such as teleportation and alternate universes and is, by all accounts, the weirdest stuff known to man.”

Fast-forward to June 10 of this year. One news story began: “IBM shares hit an all-time high Tuesday as the company showcased what it called a ‘viable path’ to building the world’s first large-scale, ‘fault-tolerant’ quantum computer by the end of the decade.”

So, yeah! Quantum computing by 2030! Nailed it!

Though not exactly on your desk. The IBM machine looks more like a cross between a data room and a moonshine still, and might not fit in my Manhattan apartment. But apparently we’re getting there.

And to be fair, in 1999, the year 2030 was so far away that it seemed like we’d be living like the Jetsons by then.

I actually first heard about quantum computing from IBM. In the 1990s and 2000s, one of my favorite things to do as a journalist was spend a day at IBM Research in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., bopping from scientist to scientist and learning about all the crazy shit they were working on.

Some of those visits took me to the lab of Charles Bennett, who would regularly blow up my brain by telling me things like why teleportation will really work. (Bennett, btw, is in his 80s and still a Research Fellow at IBM.) On a 1999 visit, he told me about the emerging concept of quantum computing. Here’s a distillation of that conversation that I put in my story:

“On the theory side, quantum mechanics delves deep into areas that are nearly unthinkable. For instance, it’s possible that a quantum computer holds an infinite number of right answers for an infinite number of parallel universes. It just happens to give you the right answer for the universe you happen to be in at the time. ‘It takes a great deal of courage to accept these things,’ says Charles Bennett of IBM, one of the best-known quantum computing scientists. ‘If you do, you have to believe in a lot of other strange things.’”

Another IBM scientist, Isaac Chuang, at the time was working with well-known MIT physicist Neil Gershenfeld on building one of the first baby-step quantum computers. The key to quantum computing – a quantum computer’s version of a transistor – is the qubit. Cheung and Gershenfeld had recently built a three qubit computer.

A qubit is an atom that’s been put into a superposition, meaning that it’s both “on” and “off” at the same time. That’s like someone saying yes and no at the same time, and whether you get an answer of yes or no depends on the universe you’re in. You might get a yes, but the version of you in a different universe gets a no. The superposition is why quantum computers can calculate vast amounts of information at once, instead of sequentially like traditional computers do. They’re calculating all the possible answers at the same time.

Compare that to today’s AI, which relies on vast seas of chips in huge data centers. Each of those sequentially-calculating chips has to coordinate and work on a question in parallel with boatloads of other chips to get the fast answers you expect. So it takes hundreds of thousands of chips.

Theoretically, you could get the same speedy result by using a quantum computer the size of a beer can.

In 1999, moving from just three qubits to four qubits was a giant challenge that lots of scientists all over the world were working on. We’ve come a long way. The Starling quantum computer IBM says it will deliver in 2029 will use 200 qubits.

Think even 200 qubits doesn’t sound like much? Says IBM: “Representing the computational state of IBM Starling would require the memory of more than a quindecillion of the world's most powerful supercomputers.”

I asked Claude AI how to imagine the number “quindecillion.” It informed me that it is close to the total number of atoms in our planet.

In short, quantum computers will give us computing power we can’t even imagine, in a package that will seem microscopic compared to the expansive data centers now being built to run AI. (In about 20 years, what are the odds that those data centers will become like today’s abandoned old shopping malls?)

Of course, IBM isn’t the only company working on quantum computers. In 1999, I talked to scientists at Hewlett-Packard who were working on one. So was a scientist at AT&T’s Bell Labs. The federal government funded quantum computing research at Lawrence Livermore Labs.

These days, Microsoft, Google, Amazon and D-Wave Systems (one of the first quantum computing startups) are in the game. So are a bunch of other startups, such as Rigetti Computing and IonQ. Venture capital investment in quantum computing companies has quadrupled since 2020.

The science is proven. The technology to make quantum computing practical is emerging. These things are coming. So if not by 2030, then maybe by 2040 I’ll have a liquidy quantum computer sloshing around on my desk.

—

This is the story as it ran in USA Today on July 14, 1999, as accessed on Newspapers.com.