Kevin Maney's Blog

November 19, 2025

The Crash of '87...and Maybe the Next One

Worries about another stock market crash keep ratcheting higher. Back in 1987, I had a close-up view of a previous crash. If and when there’s a next one, in many ways it won’t look like 1987, and in many ways it no doubt will.

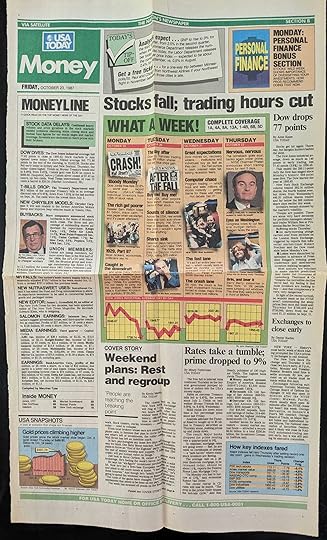

Well, here’s one way it won’t be the same. I wrote this in a story that appeared on Friday, October 23, 1987 – the end of a wild week that started with a market meltdown that Monday.

Making its rounds is the Billy Martin Theory: that every time Martin gets rehired to manage the New York Yankees baseball team, the market drops. He was hired for the fifth time on Monday.

Billy Martin died in 1989.

Anyway, here’s some backstory: In the fall of 1987 I had been a journalist in the Money section at USA Today for a little more than two years. When the biggest business story of the year exploded – that would be the crash on Monday, October 19 – I got put in the hot seat.

On that Monday, I wrote Tuesday’s page one story about the crash. On Wednesday, I contributed to Thursday’s cover story about Wall Street’s tentative rebound. And then on Thursday I wrote another cover story for Friday’s paper, headlined “WHAT A WEEK! Weekend plans: Rest and regroup.”

Me and the ‘87 crash – we got intimate.

One thing that’s always true about market crashes: lots of people worry that one is coming, and then everybody is surprised when it arrives.

From lots that I’ve read about it, that seems to have been true in 1929. It was true in 1987. The same in 2000 and 2008. Can’t imagine it won’t be true next time. The opening line of my Tuesday story: Doom swallowed Wall Street Monday. Bad news was expected, but the crash reached a scale nobody could have imagined.

Stocks had been ablaze in the mid-1980s. Remember yuppies? Short for “young upwardly-mobile professionals”? In the ‘80s they were early-career Baby Boomers suddenly making a lot of money and indulging in “power suits,” BMWs, IBM PCs…and stocks.

Money was pouring into stocks and mutual funds. Wall Street was the red-hot center of American culture. Hollywood made the iconic movie Wall Street, starring Michael Douglas and a pre-nutty Charlie Sheen, in which Douglas’ character famously evangelized why “Greed is good.” (And then the movie came out in December 1987, after the real Wall Street crumbled.)

About a month before the ‘87 crash, markets had started stalling. Interest rates and inflation were heading higher – both usually bad news for stocks. Investor confidence was wavering. But most investors stayed in, telling themselves that the moment would pass and the economy was strong and markets would continue to march higher.

By the time I got to work on that Monday, panic was already in the air. Stocks were diving. Anticipating trouble, New York closed Wall Street to traffic. People started crowding the street in front of the New York Stock Exchange. I never could figure out what they thought they’d see. A financial executive jumping off the roof?

By the end of that day, stocks fell almost 23%, wiping out about $500 billion in value – equal to $1.4 trillion today. That first-day story was mostly about market statistics and chaos – the crazy day that brokers and investors experienced. I was collecting information and writing as the crash was happening. One of my colleagues went to Wall Street and filed some on-the-scene details for the story. My favorite:

But doing well were drug dealers who plied their trade on Pine Street, two blocks from the nondescript marble stock exchange building. Men in three-piece suits were buying $25 bags of marijuana at a brisk clip. “I’m doing a great deal more than usual,” said a dealer who wouldn’t give his name. He said he hoped to do $1,000 Monday.

See, that shows a way a new crash won’t be like the ‘87 crash. There are now about a half-dozen dispensaries within a 15-minute walk of Wall Street. Bummed-out traders can get stoned legitimately.

Then the Thursday story read like a sigh of relief. On that Tuesday and Wednesday stocks regained about half their losses. Aggressive investors had figured that stocks had fallen so far, they were on sale. Thomas Czech, a markets analyst at since-defunct Blunt Ellis & Loewi in Minneapolis, told us: “We see a large increase in greed here. We’re seeing people throwing money fast and hard and maybe without thinking.”

The misplaced optimism, of course, reversed itself and led to stocks diving again on Thursday. On Friday, with brokers, traders and officials exhausted and overwhelmed, the NYSE closed two hours early.

And that’s another way a crash today would be different. Isn’t all the trading now by computer? Are any humans even on the NYSE floor? Who’s there to get exhausted?

Oh, another difference vs. 1987: Now you can go online and watch your stocks plummet in real time. This was in my Friday story:

The Associated Press’ stock tables – the only stock figures for millions of investors – have wheezed all week. Closing prices often didn’t make it into member newspapers.

A lot of people didn’t know how badly they got hit for days.

Finally, there is another commonality to all market crashes: In its aftermath, much of the public is glad to see some full-of-themselves richy-rich class get their ass kicked. I wrote:

Psychologists popped up everywhere saying that the money-grubbing Y-word class has finally learned its lesson. “There’s a great deal of glee out there that greed has finally caught up with these people,” says Linda Barbanel, a New York psychotherapist who calls herself the Dr. Ruth of money.

Here in 2025, it’s the AI bros who are most at risk for a comeuppance.

I can tell you one thing they must avoid at all costs: building an AI Billy Martin and tempting the Yankees to hire it as manager.

–

These are the pages and stories from Tuesday, October 20, 1987, and Friday, October 23, 1987.

October 18, 2025

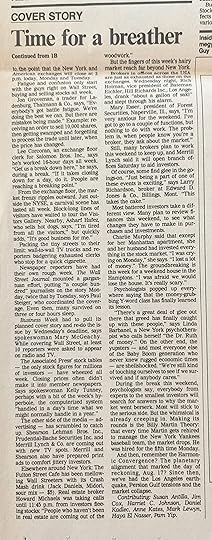

Oh, That Larry Ellison

I interviewed Oracle CEO Larry Ellison in person just once, in 2002. The main things I have long remembered about it were that the room was dark, Ellison acted like he wished I’d go away, and he had two bodyguards, each looking like they could bench press a subway car.

The details of my time with Ellison only came back to me once I re-read the story that I wrote back then. I was reminded of how odd Ellison was – and in all likelihood still is, now that he’s good buds with Trump and working with his son, David, to control a sizable chunk of American media.

Even before I met Ellison, I didn’t much admire the kind of character he was on the tech scene. The short version is that he seemed to enjoy being something of tech’s Darth Vader. He had a reputation for publicly clashing with and/or sacking his own executives, trash-talking other tech companies’ CEOs, and hiring private investigators to find dirt on Microsoft CEO Bill Gates, even having them rummage through Gates’ trash and pay off Microsoft janitors for tips. Ellison considered Gates his arch-rival and seethed at Microsoft’s success – particularly that Microsoft had more success than Oracle.

“I still believe we’ll be the number one software company in the world,” Ellison told me in that shadowed room back then. “We’ll pass Microsoft.” Hm, well, Microsoft is worth $3.8 trillion. Oracle, about $823 billion. So that didn’t happen.

Here’s how I described Ellison in my piece: “Ellison is this peculiar mix of, on one side, a MiG-flying, America’s Cup-racing, babe-magnet zillionaire playboy; and on the other side, a geek who can get excited about improving Web server response time by a few microseconds.”

I was disappointed, as a journalist, that I got the latter. He wanted to tell me all about software called clustering that was going to make Oracle’s databases more reliable. “It’s a huge breakthrough in computer science,” he said, and apparently it was, though for the general public that revelation was about as exciting as hearing of a new kind of automobile suspension system.

I also noted in the story: “Ellison once broke his neck surfing, then broke his arm in 28 places in a biking accident while recovering from breaking his neck. He almost died in a sailing incident a couple of years ago, and now he’s bought a boat so he can compete in the next America’s Cup yacht race.” Some people admire that kind of thing. Oracle shareholders no doubt didn’t much appreciate their CEO constantly middle-fingering death.

My interview with Ellison was arranged by his PR people, for right after he gave a speech to a tech industry group. So first I attended the speech. He used it to again poop on Microsoft.

“If you really want 50 machines that break all the time and require lots of labor, go with the guys in Redmond,” Ellison said on stage. (Just in case you don’t know, Microsoft has long been headquartered in Redmond, Wash.) Then he knocked IBM for following Microsoft’s technological path. “It must have been the unreliability that appealed to them,” Ellison said of IBM.

Once the speech was over, I was to meet Ellison backstage to talk. That’s when I encountered the bodyguards, who as soon as I walked in bolted to get between me and Ellison. They only let me pass once the PR person said, “He’s OK.” As I wrote: “For a couple of minutes, it’s like I’ve entered a Sopranos episode.”

Anyway, now it’s 23 years later. Ellison is 81, having outlasted his physical recklessness. He’s worth about $365 billion, so on one measure he’s whipped Gates, who today is worth around $105 billion. Oracle is back in the headlines because of its relationship with OpenAI and the Ellison family’s control of Paramount Skydance.

And, apparently, these days all the rich tech people have bodyguards. I didn’t realize that Ellison was ahead of the curve on that one.

“As I get up to go, it seems for a moment like there are two Larry Ellisons,” I wrote at the conclusion of my story. “There’s the crazy cartoonish version for public consumption, which he left onstage. And there’s this one in the back room, who seems quite a bit more human and far less outrageous. I’m not sure which one is more real.”

Still don’t know.

—

This is the article as it originally appeared in USA Today on February 13, 2002.

September 28, 2025

General Catalyst, Four Books, Ten Years and Lots of Billions

I first met Hemant Taneja in November of 2013. We were set up by a PR person who thought I’d find Hemant interesting, and we planned to meet at 5 pm at the bar at Café Luxembourg on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

I’m not sure what we ordered. A beer? Cocktail? We sat on barstools and I, wearing my journalist hat as tech columnist for Newsweek, likely started with small talk (Why are you in New York?) and then asked Hemant about himself and his work.

I had not before heard of Hemant. I was not familiar with his firm, General Catalyst. I knew tons of VCs and had relationships with the top firms, but General Catalyst, or GC, at the time was a lesser player. Hemant was best known for having made a major early bet on Stripe, which, in 2013, I couldn’t understand. Stripe was tiny, and it seemed to me and a whole lot of others in tech that Stripe was just another me-too payments platform, which the world wouldn’t need. (Of course, Stripe turned out to be one of the more brilliant early-stage investments. It’s now worth north of $100 billion.)

As we talked, Hemant told me about a concept that he called “unscaling.” Basically, it’s the idea that AI, the cloud, mobile devices, internet of things and other recent technologies will increasingly allow companies to do the opposite of mass-production, mass-marketing, mass-media and all the other twentieth-century “economies of scale” stuff that was designed to sell the most of the same thing to the most people.

Instead, unscaled companies will increasingly offer highly-individualized products and services that seem to be built specifically for one person. Much of that is happening today, accelerated by AI.

I’ve always been a sucker for big ideas that seem to explain something about how the world is changing, and I remember coming away from that meeting with the unscaling theory circling my brain. I started slipping the idea into Newsweek columns. I talked about unscaling some more with Hemant. The next time I was in the Bay Area, I visited him at GC’s small office there.

Sometime in 2015, after I’d written a few times about unscaling, Hemant and I met again in New York and he suggested that we should do a book together about it. I had just finished co-authoring Play Bigger, which would come out in June 2016, and was ready for a new project. We put together a proposal and sold the book idea to the publisher Public Affairs. Oddly enough, the editor who bought it was John Mahaney, who bought and edited my first book, Megamedia Shakeout, 22 years earlier.

So, Hemant and I wrote Unscaled: How AI and a New Generation of Upstarts Are Creating the Economy of the Future. It came out in 2018, apparently a good four years too early. At the time, the topic of how AI was going to upend industries across the spectrum wasn’t yet on most people’s radar. Now it’s all anyone in business talks about.

One of the chapters in Unscaled focused on healthcare. By the time the book hit the market, Hemant and General Catalyst were investing big in healthcare technologies, with a belief that AI could reinvent the sector. We decided healthcare needed a whole book of its own. Hemant brought Steve Klasko into that project. Klasko was CEO of Jefferson Health in Philadelphia, and was partnering with General Catalyst. The three of us wrote and published UnHealthcare: A Manifesto for Health Assurance.

One goal of that book was to establish a new category of healthcare that was all about using technology to keep people well and out of hospitals and doctor’s offices, and we called that category “health assurance.”

UnHealthcare came out in 2020. Almost immediately, Hemant and I started on yet another book, this time about how “responsible innovation” and how to build companies that would help (and not hurt) society. Intended Consequences was published in 2022. In tandem, Hemant set up the non-profit Responsible Innovation Labs, which helps founders build responsible-innovation companies.

Throughout all of this, Hemant was remaking General Catalyst, and he and the firm were hitting home runs with both companies it invested in and, more unusual for VCs, companies it helped start. Stripe and Samsara were big investment wins. So was Snapchat and Airbnb. Hemant co-founded Livongo, which eventually got bought for $18 billion.

In the early 2000s, GC was a regional firm based in Boston and had $257 million in assets under management (AUM). By late 2024, its AUM was $33.2 billion and GC operated nine offices globally, including in Silicon Valley, New York, London, Berlin and Mumbai. In 2025, when Time magazine ranked America’s top VC firms, General Catalyst landed at No. 2, just behind Accel and one ahead of Andreessen Horowitz.

After Intended Consequences I thought we were done writing books. But on another visit to New York, over another cocktail (this time at the Crosby Hotel Bar, in November 2022), Hemant said we should do one more – a book that would capture the core principles that guide him and his firm. I remember thinking: That seems like something a lot of people would want to read, given GC’s outsized success and Hemant’s growing fame.

At the heart of those principles would be General Catalyst’s belief that companies that benefit society and solve hard problems like climate change and the U.S. healthcare mess offer the best returns over the long haul. I loved it and signed on.

The book took about 15 months to complete. BenBella Books published it on Sept. 23. It’s titled The Transformation Principles: How to Create Enduring Change. The book details nine of these principles:

— The business must have a soul.

— Navigating ambiguity is more valuable than predicting the future.

— Creating the future beats improving the past.

— Those who play their own game win.

— Serendipity must become intentional.

— For great change, radical collaboration beats disruption.

— Context constantly changes, but human nature stays the same.

— The choice between positive impact and returns is false.

— The best results come from leading with curiosity and generosity.

Available wherever books are sold.

September 17, 2025

AI and the Pace of Change Scrambling Your Brain? Wimp!

In 1997, a lot of us felt like the world was changing at a velocity humans had never experienced. The internet was the main driver. It exploded into our lives after the release of the Mosaic browser in October 1994. Within a couple of years, the dot-com boom shattered business models and allowed us to think of new ways to do almost everything.

Compared to today, though, the pace of change in the 1990s seems like it was as slow as the comedy on “The Carol Burnett Show.” (If you haven’t watched lately, give it a try – you’ll see what I mean.) AI is upending everything. Famed Economist Tyler Cowan even co-wrote an article titled, “AI Will Change What It Is To Be Human. Are We Ready?” Sounds scary!

Well, allow me to offer a different perspective.

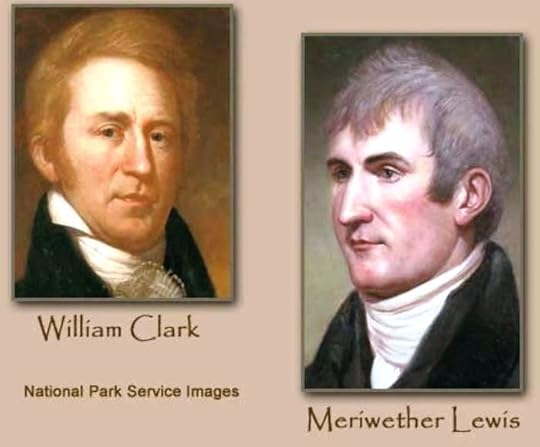

In 1996, Stephen Ambrose published his bestselling book Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. It is a detailed and gripping account of the Lewis and Clark expedition across the unmapped Western U.S. I read it soon after it first came out, and was totally fascinated.

The book made me wonder – amid the dot-com boom – what Ambrose would think of technological change and the human experience. So I called him. (As a journalist writing for USA Today, then the largest circulation newspaper in the U.S., you get to do such things.)

“Which half century experienced the most technological change since the beginning of time?” Ambrose said over the (land-line!) phone, repeating the question I’d asked him.

His answer surprised me: Nothing compares to the early 19th century – which was the time of Lewis and Clark, who set out from near what is now St. Louis in May 1804.

Ambrose referred me to a passage in Undaunted Courage:

Since the birth of civilization, there had been almost no changes in commerce or transportation. Technology was barely advanced over that of the Greeks. The Americans of 1801 had more gadgets, better weapons, a superior knowledge of geography and other advantages over the ancients, but they could not move goods or themselves or information by land or water any faster than had the Greeks and Romans.

As I wrote in my subsequent article about the experience of living in 1800: “Nothing could move faster than a horse. As far as people then knew, nothing ever would move faster than a horse.”

Ambrose in the book also quotes Henry Adams, who wrote in the late-1800s about conditions in Jefferson’s era: “Experience forced on men's minds the conviction that what had ever been must ever be.”

Ambrose told me: “At the beginning of the 19th century, people thought nothing was possible. By the end of the century, people thought anything was possible.”

By the mid-1800s, railroads criss-crossed the nation, carrying people and goods at 25 miles per hour. (Over long distances, a horse with a rider could at best go about 25 miles per DAY.) The telegraph, first used in 1844, moved information instantly. By late in that century, electricity powered streetcars and factories. Electric lights turned night into day.

Sure, the actual pace of change is greater right now than ever. But the nearly-unfathomable difference is that we have all lived our lives expecting change. The experience of everyone today is that technology advances and new inventions are constantly coming into our lives. Rapid change might be hard to keep up with, but it’s not alien to us.

So imagine when, generation after generation, there was little conception of progress. People learned their jobs from their parents who learned from their grandparents, and nobody expected to do those jobs differently. They had no reason to anticipate technological change. Doing so then would be like us today expecting time travel to be something we’d soon be able to book on Expedia.

We of the AI era are not as uniquely challenged as we might want to believe.

While I had Ambrose on the phone, I asked why he thought Undaunted Courage got so much attention. It sold far better than any of his other books at that point. Disney, Robert Redford and Ted Turner all called him about turning the book into a movie. (Never happened.)

“One reason, I think, is that it’s almost like science-fiction in reverse,” he told me.

When going 12 miles in a day was good. When it was a feat to tell time while traveling. When it was common for a mother to go a year without knowing any information about her son living a couple of states away. To us, understanding just how that worked is exotic.

Ambrose told me he wished he’d realized that when he wrote the book. “I’d have put more of it in there.”

Ambrose died in 2002 at 66, from lung cancer. I spoke to him only that one time.

–

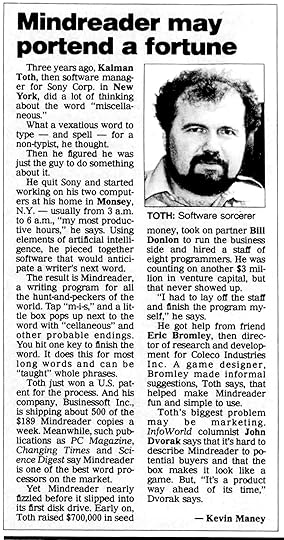

Here is the column as it appeared in the Reno Gazette-Journal on Feb 3, 1997. It was distributed through Gannett News Service so ran in many papers across the U.S.

AI and the Pace of Change Scambling Your Brain? Wimp!

In 1997, a lot of us felt like the world was changing at a velocity humans had never experienced. The internet was the main driver. It exploded into our lives after the release of the Mosaic browser in October 1994. Within a couple of years, the dot-com boom shattered business models and allowed us to think of new ways to do almost everything.

Compared to today, though, the pace of change in the 1990s seems like it was as slow as the comedy on “The Carol Burnett Show.” (If you haven’t watched lately, give it a try – you’ll see what I mean.) AI is upending everything. Famed Economist Tyler Cowan even co-wrote an article titled, “AI Will Change What It Is To Be Human. Are We Ready?” Sounds scary!

Well, allow me to offer a different perspective.

In 1996, Stephen Ambrose published his bestselling book Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West. It is a detailed and gripping account of the Lewis and Clark expedition across the unmapped Western U.S. I read it soon after it first came out, and was totally fascinated.

The book made me wonder – amid the dot-com boom – what Ambrose would think of technological change and the human experience. So I called him. (As a journalist writing for USA Today, then the largest circulation newspaper in the U.S., you get to do such things.)

“Which half century experienced the most technological change since the beginning of time?” Ambrose said over the (land-line!) phone, repeating the question I’d asked him.

His answer surprised me: Nothing compares to the early 19th century – which was the time of Lewis and Clark, who set out from near what is now St. Louis in May 1804.

Ambrose referred me to a passage in Undaunted Courage:

Since the birth of civilization, there had been almost no changes in commerce or transportation. Technology was barely advanced over that of the Greeks. The Americans of 1801 had more gadgets, better weapons, a superior knowledge of geography and other advantages over the ancients, but they could not move goods or themselves or information by land or water any faster than had the Greeks and Romans.

As I wrote in my subsequent article about the experience of living in 1800: “Nothing could move faster than a horse. As far as people then knew, nothing ever would move faster than a horse.”

Ambrose in the book also quotes Henry Adams, who wrote in the late-1800s about conditions in Jefferson’s era: “Experience forced on men's minds the conviction that what had ever been must ever be.”

Ambrose told me: “At the beginning of the 19th century, people thought nothing was possible. By the end of the century, people thought anything was possible.”

By the mid-1800s, railroads criss-crossed the nation, carrying people and goods at 25 miles per hour. (Over long distances, a horse with a rider could at best go about 25 miles per DAY.) The telegraph, first used in 1844, moved information instantly. By late in that century, electricity powered streetcars and factories. Electric lights turned night into day.

Sure, the actual pace of change is greater right now than ever. But the nearly-unfathomable difference is that we have all lived our lives expecting change. The experience of everyone today is that technology advances and new inventions are constantly coming into our lives. Rapid change might be hard to keep up with, but it’s not alien to us.

So imagine when, generation after generation, there was little conception of progress. People learned their jobs from their parents who learned from their grandparents, and nobody expected to do those jobs differently. They had no reason to anticipate technological change. Doing so then would be like us today expecting time travel to be something we’d soon be able to book on Expedia.

We of the AI era are not as uniquely challenged as we might want to believe.

While I had Ambrose on the phone, I asked why he thought Undaunted Courage got so much attention. It sold far better than any of his other books at that point. Disney, Robert Redford and Ted Turner all called him about turning the book into a movie. (Never happened.)

“One reason, I think, is that it’s almost like science-fiction in reverse,” he told me.

When going 12 miles in a day was good. When it was a feat to tell time while traveling. When it was common for a mother to go a year without knowing any information about her son living a couple of states away. To us, understanding just how that worked is exotic.

Ambrose told me he wished he’d realized that when he wrote the book. “I’d have put more of it in there.”

Ambrose died in 2002 at 66, from lung cancer. I spoke to him only that one time.

–

Here is the column as it appeared in the Reno Gazette-Journal on Feb 3, 1997. It was distributed through Gannett News Service so ran in many papers across the U.S.

August 18, 2025

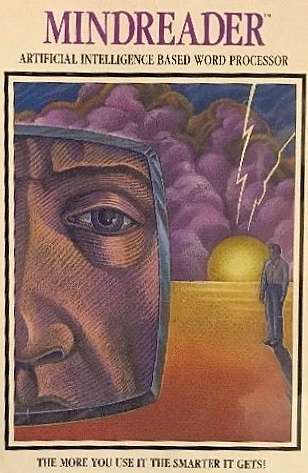

AI From 1986, Reading Minds...Badly

The first time I wrote the words “artificial intelligence” in a published article was, apparently, in 1986.

Here’s what was exciting (then!) about that 1986 AI: It was the kind of autocomplete function that we all experience today when we try to text “mortadella” and it gets changed to “mortgage.”

You know, then the text goes out as: “Hey, you good with a mortgage sandwich for lunch?”

I often use Newspapers.com to find old articles. It’s a searchable archive of more than 29,000 newspapers, some going back to the 1800s. Included are every newspaper I’ve ever written for. (I haven’t been writing since the 1800s, though sometimes it feels that way.) These days, like just about everyone else, I’m writing, thinking, and talking about AI a whole lot. So I wondered when I first encountered it as a journalist covering technology.

Turns out it was 1986, and once I saw the story, I realized it was thanks to a burly bear of a guy named Kalman Toth and his software product called Mindreader.

I vaguely remember Toth. I do remember Mindreader because he let me test it out. The software was the right idea too early. That it worked at all was miraculous. But it didn’t work well. I’m pretty sure I turned it off before long.

The Mindreader back story: Toth worked on software for Sony in its New York offices. For Lord knows what reason, he got thinking about the word “miscellaneous” and how hard it can be to spell and to type that word out. He quit Sony and started writing code to solve the miscellaneous problem.

The sentence I wrote when I first typed the words “artificial intelligence” was this: “Using elements of artificial intelligence, he pieced together software that would anticipate a writer’s next word.”

Yeah, so when you’d type “mis” it would automatically add “cellaneous.” Mind blown!

Toth started a company, Businessoft, to sell Mindreader at $189 a pop. He landed a seed investment of $700,000, but failed to get any more funding.

I don’t know much about what happened to Toth or Businessoft after I wrote about him. In 1988, another company, Brown Bag Software, released Mindreader 2.0. A site called WinWorld acknowledged that Mindreader was “originally written by Kalman Toth of BusinesSoft (sic).” You can go to that page to see what Mindreader looked like. Whoever wrote about it also concluded that the software wasn’t that useful: “The majority of its suggestions seemed irrelevant, and the auto complete does not really act as a spell checker.”

Otherwise, though, I searched all over the internet. Toth, his company and his pioneering AI seem to have vanished in the 1980s. Another software company called BusinesSoft was founded in Bulgaria in the 1990s – and still exists. It doesn’t do anything like Mindreader.

Toth is one of those too-early innovators lost to history. What he started with Mindreader has become part of our everyday lives. As I’m typing this in a Google Doc, it’s offering to complete words and sentences.

What I know now that I didn’t in 1986 is that Mindreader was a casualty of running afoul of the adjacent possible.

When my firm works with leadership teams on creating new market categories, it always involves a conversation about the adjacent possible. If you consider that there is a “possible” (all the technology that we already use) and the “not-yet-possible” (technology not yet invented or not yet very workable), then there is a border between them called the adjacent possible.

When a new technology lands in the adjacent possible, it’s new enough to be cool and amazing but mature enough to actually work well. Which is when a new technology catches on.

Mindreader was too far into the not-yet-possible. By the time more advanced versions of autocomplete entered the adjacent possible, Toth’s company had long run out of money and faded away.

(One related point: If a company is building a product that lands squarely in the possible, it’s entering an existing market and trying to scrape out a few points of market share. Those companies aren’t creating new market categories.)

Anyway, back to Mindreader. Today’s generative AI is sometimes described as superpowered autocomplete, kind of a great-great-great-grandchild of Mindreader’s technology. In fact, when I asked Anthropic’s Claude to describe how its technology works, it responded:

Think of a large language model like an incredibly sophisticated autocomplete system that has read virtually everything ever written on the internet. When you type a message, it doesn't actually “understand” what you're saying in the way humans do – instead, it's making incredibly nuanced predictions about what word should come next based on the patterns it learned from analyzing billions of text examples.

Claude went on:

It's like having a friend who has memorized every conversation, book, and article ever written, and when you start a sentence, they can finish it by drawing on all those patterns – except this friend processes all that information simultaneously and can predict not just the next word, but entire coherent responses.

In other words, it’s a lot like a mindreader.

—

This is the article as it appeared in USA Today on February 13, 1986, as accessed on Newspapers.com:

June 12, 2025

Data Center In a Beer Can?

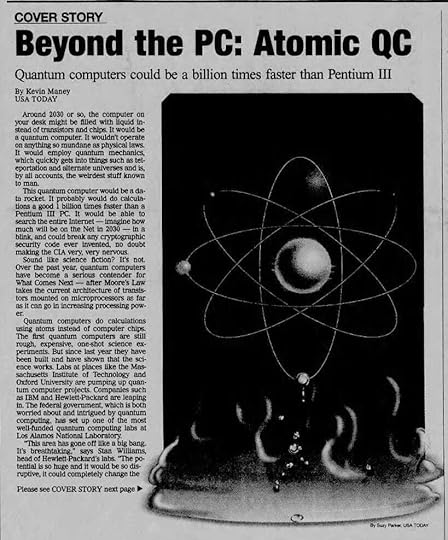

In July 1999, I opened a story for USA Today like this:

“Around 2030 or so, the computer on your desk might be filled with liquid instead of transistors or chips. It would be a quantum computer. It wouldn’t operate on anything so mundane as physical laws. It would employ quantum mechanics, which quickly gets into things such as teleportation and alternate universes and is, by all accounts, the weirdest stuff known to man.”

Fast-forward to June 10 of this year. One news story began: “IBM shares hit an all-time high Tuesday as the company showcased what it called a ‘viable path’ to building the world’s first large-scale, ‘fault-tolerant’ quantum computer by the end of the decade.”

So, yeah! Quantum computing by 2030! Nailed it!

Though not exactly on your desk. The IBM machine looks more like a cross between a data room and a moonshine still, and might not fit in my Manhattan apartment. But apparently we’re getting there.

And to be fair, in 1999, the year 2030 was so far away that it seemed like we’d be living like the Jetsons by then.

I actually first heard about quantum computing from IBM. In the 1990s and 2000s, one of my favorite things to do as a journalist was spend a day at IBM Research in Yorktown Heights, N.Y., bopping from scientist to scientist and learning about all the crazy shit they were working on.

Some of those visits took me to the lab of Charles Bennett, who would regularly blow up my brain by telling me things like why teleportation will really work. (Bennett, btw, is in his 80s and still a Research Fellow at IBM.) On a 1999 visit, he told me about the emerging concept of quantum computing. Here’s a distillation of that conversation that I put in my story:

“On the theory side, quantum mechanics delves deep into areas that are nearly unthinkable. For instance, it’s possible that a quantum computer holds an infinite number of right answers for an infinite number of parallel universes. It just happens to give you the right answer for the universe you happen to be in at the time. ‘It takes a great deal of courage to accept these things,’ says Charles Bennett of IBM, one of the best-known quantum computing scientists. ‘If you do, you have to believe in a lot of other strange things.’”

Another IBM scientist, Isaac Chuang, at the time was working with well-known MIT physicist Neil Gershenfeld on building one of the first baby-step quantum computers. The key to quantum computing – a quantum computer’s version of a transistor – is the qubit. Cheung and Gershenfeld had recently built a three qubit computer.

A qubit is an atom that’s been put into a superposition, meaning that it’s both “on” and “off” at the same time. That’s like someone saying yes and no at the same time, and whether you get an answer of yes or no depends on the universe you’re in. You might get a yes, but the version of you in a different universe gets a no. The superposition is why quantum computers can calculate vast amounts of information at once, instead of sequentially like traditional computers do. They’re calculating all the possible answers at the same time.

Compare that to today’s AI, which relies on vast seas of chips in huge data centers. Each of those sequentially-calculating chips has to coordinate and work on a question in parallel with boatloads of other chips to get the fast answers you expect. So it takes hundreds of thousands of chips.

Theoretically, you could get the same speedy result by using a quantum computer the size of a beer can.

In 1999, moving from just three qubits to four qubits was a giant challenge that lots of scientists all over the world were working on. We’ve come a long way. The Starling quantum computer IBM says it will deliver in 2029 will use 200 qubits.

Think even 200 qubits doesn’t sound like much? Says IBM: “Representing the computational state of IBM Starling would require the memory of more than a quindecillion of the world's most powerful supercomputers.”

I asked Claude AI how to imagine the number “quindecillion.” It informed me that it is close to the total number of atoms in our planet.

In short, quantum computers will give us computing power we can’t even imagine, in a package that will seem microscopic compared to the expansive data centers now being built to run AI. (In about 20 years, what are the odds that those data centers will become like today’s abandoned old shopping malls?)

Of course, IBM isn’t the only company working on quantum computers. In 1999, I talked to scientists at Hewlett-Packard who were working on one. So was a scientist at AT&T’s Bell Labs. The federal government funded quantum computing research at Lawrence Livermore Labs.

These days, Microsoft, Google, Amazon and D-Wave Systems (one of the first quantum computing startups) are in the game. So are a bunch of other startups, such as Rigetti Computing and IonQ. Venture capital investment in quantum computing companies has quadrupled since 2020.

The science is proven. The technology to make quantum computing practical is emerging. These things are coming. So if not by 2030, then maybe by 2040 I’ll have a liquidy quantum computer sloshing around on my desk.

—

This is the story as it ran in USA Today on July 14, 1999, as accessed on Newspapers.com.

May 19, 2025

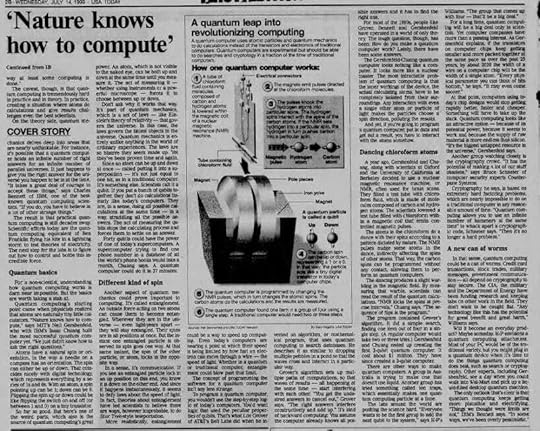

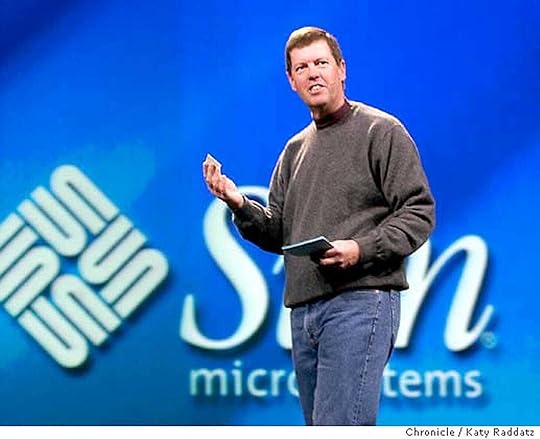

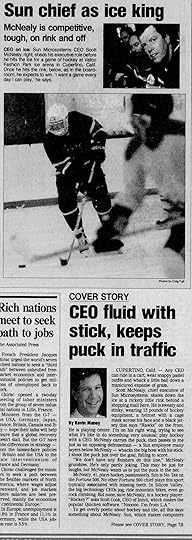

Pucking Around With Sun's CEO

It’s hockey playoff season, which prompted me to pull out this old story…

In the 1990s, in the middle of the dot-com boom, Sun Microsystems was one of the most explosively hot companies in the world.

While mind-boggling to consider today, in 1996 Sun got to within a few hours of announcing that it was going to buy Apple for around $5 a share. Apple was a train wreck. Steve Jobs had not yet returned. Sun was worth billions and its CEO, Scott McNealy, was a tech industry giant. The $5 a share offer was actually a huge premium. Apple shares that year had fallen below $1.

“We wanted to do it,” McNealy told a Silicon Valley dinner crowd in 2011. “There was an investment banker on the Apple side, an absolute disaster, and he basically blocked it. He put so many terms into the deal that we couldn’t afford to go do it.”

McNealy added: “If we had bought Apple, there wouldn’t have been iPods or iPads … I’d have screwed that up,”

It’s hard to even imagine what the world would be like right now if Sun had succeeded in scooping up Apple. No iPhones. No Apple TV. Maybe not even an Apple brand.

Anyway, since McNealy was such a huge character at the time, and I was a technology journalist for USA Today, I wanted to write a feature story about him. But I wanted a unique way to do it. So, I played ice hockey with him on his team.

By 1996, I had talked to McNealy many times – sometimes for interviews, and sometimes more socially at conferences such as PC Forum. I liked him. He was insightful about where technology was heading. Just as the consumer internet was being born, McNealy’s prescient motto – which became Sun’s motto – was “the network is the computer.” He was funny and irreverent. He’d say insulting things about Bill Gates during a time when Microsoft was the superpower of the tech universe. He loved mocking big consulting firms, saying in a talk I attended that their slogan should be: “You’ve got money; we’ve got a Hoover.”

Somewhere along the way, I learned that McNealy, who grew up in the Detroit area, played hockey. I grew up playing hockey in Binghamton, N.Y. So, sometimes we’d talk about our shared sport. That’s how the story concept came to mind. As far as I knew, I was the only technology journalist who played hockey, and so if I could play hockey with McNealy, I’d be able to write a story from a perspective that no one else could touch.

To McNealy’s credit, he thought this sounded like a “cool” idea. (He liked the word “cool.”) I packed up my hockey gear, flew to San Francisco, and met McNealy at a not-very-impressive rink behind a shopping center in Cupertino, Calif. He was then 41, and I was 36.

I was to play on McNealy’s team in a well-organized pickup game. A group from Sun met at this rink every week, split up into two teams, and played for about 90 minutes. To get really up close and personal, I played on his line – McNealy played center; I was his right wing.

This was not like Trump playing golf and “winning” every tournament. Or like Putin playing hockey and miraculously scoring eight goals in a game. Most everyone on the other team were Sun employees. They didn’t cut McNealy one bit of slack.

I wrote that the other players “tangle with him on the boards, run into him, steal the puck from him.” I gave McNealy one pass that sent him in on a breakaway, one on one against the goalie. The goalie stuffed him. After the game, I talked to the goalie – Jeff Zank, then an engineering manager at Sun. “Sometimes I joke that I have to let him score one or two to keep him happy,” Zank said. “But that’s not reality. He doesn’t get any special treatment. In fact, it might go a little the other way.”

McNealy didn’t cut me any slack, either. No coddling the journalist. He fed me one pass and I shot the puck over the net. He griped, “We don’t have any finishers on this line.” (I finally scored late in the game when I tipped in a shot from the blue line. He, I will note, did not.)

But actually, the whole evening was a blast. I enjoyed playing with him. I wrote in the story that he was a good passer, could hold the puck well in tight spaces, and worked hard to get to loose pucks and help in defense. Also, I said in the story that he was “stinky” under all that hockey gear – which he needled me about for years after.

Of course, the story was meant to shed some light on McNealy, not just report on an amateur hockey game in a rickety rink. He co-founded Sun in 1982. It started out making powerful desktop computers for business, dubbed “workstations” back then. Once the internet arrived, Sun made servers that could host web sites. The company helped develop the open-source software movement, and created the Java language for mobile computing. At its peak in 2000, Sun was valued at about $200 billion — super impressive in those days.

When I first met McNealy, Eric Schmidt, later of Google fame, was Sun’s chief technology officer. Ed Zander was president – he later became CEO of Motorola. One of Sun’s co-founders was Vinod Khosla, now a major VC. Kim Polese was a key member of the Java team. McNealy knew how to surround himself with top talent.

The hockey story was a window on all of that. “In business, his hockey playing adds to his aura,” I wrote. “It says he is competitive, unique, tough, fun, and even a bit childish – all adjectives that carry over to his management style.”

The post-2000 dot-com crash proved to be brutal for Sun. Sales of new machines dried up. Worse, as internet companies folded by the hundreds, they put their perfectly good Sun machines up for sale, flooding the market. Sun’s stock price collapsed and the company never got its glory days back. In 2009, Oracle bought Sun for $7.9 billion.

The way my story ended says as much about McNealy as anything.

Outside the rink, after hockey has cleansed McNealy of the executive mantle, it’s easy to see Scott the Hockey Player. The average Joe. McNealy calls his wife, Susan, on a payphone to say he’ll be home soon. He sits on a metal bench, dressed in a golf shirt, jeans, and moccasins with no socks. He sips Gatorade and becomes chatty. He pulls out a picture of his 4-month-old son Maverick and talks about the day Mav can start skating. He could be anybody.

Then he gets a thought. What if Bill Gates played hockey? What if McNealy could check him into oblivion? “That would be cool!” he says, showing that hockey and business do indeed mix.

McNealy is still very much around as an investor and board member.

Oh, and little Maverick McNealy? Yeah, he played hockey through high school. But now he’s a star on the PGA tour.

—

This is the story as it appeared in USA Today on April 2, 1996. It was accessed through Newspapers.com.

April 11, 2025

Trade Wars and the Law of Most Bests

In the early 2000s, a lot of people and politicians in the U.S. had a major issue with software jobs getting off-shored, particularly to India. Companies rushed to get rid of expensive American coders, and either set up offices in India to employ relatively cheap coders there, or hire the work out to Indian companies such as Infosys or Wipro.

Horror stories emerged of American workers being told to train the Indian workers who were going to take their jobs, or lose severance packages if they refused. (I even recorded a satirical song back then about a guy who falls in love with the woman who is about to make him redundant, titled “I Dream of Bangalore.”)

As the tech columnist at USA Today at the time, I was looking for interesting ways to write about that trend. I ended up talking to Marc Andreessen – in his pre-Andreessen Horowitz days – who waxed eloquently to me about the economic concept of comparative advantage.

It’s a concept that helps explain why tariffs and economic isolationism are the opposite of what you’d do if you want to raise the standard of living for the widest range of people.

In other words, comparative advantage describes why a system of free trade is highly beneficial. “The system works so amazingly well that it’s a wonder anyone doubts it, and, yet, of course people do,” I quoted Marc as telling me then. I added the note that Marc was “one of the few who will forthrightly say that the outsourcing trend should be cheered.”

Based on the public stances by Marc over the past six months, it may be that he’s done a U-turn on that position. News outlets have noted that he’s been silent since Trump rolled out his tariffs. In fact, Trump re-posted a chart Andreessen put on social media that showed diving federal revenue from tariffs over the past century. Trump used it to bolster his position on tariffs.

Anyway, let’s get into the idea of comparative advantage and the way Marc and another recent Trump fan, Oracle’s Larry Ellison, thought about it then.

First of all, the theory was not made up to justify early-2000s job displacement. It was first described by an economist and British member of Parliament named David Ricardo, who died in 1823. So he was around when international trade relied mostly on sailing ships and horse-drawn carriages.

You can read my longer explanation of Ricardo’s concept in the original column below. But a quickie version goes like this: Every nation benefits when every nation focuses on making and selling what it is “most best” at, and buys everything else from other “most bests.”

One way to see how that works is to look at it from a personal level.

My most best has something to do with writing. Because I do that better than most, and can be more productive at it than most, I can get paid pretty well to write. But I can’t make much, or anything at all, for my baking, or carpentry, or accounting, or a lot of other things I might do. Other people do those things way better than me, and do it more efficiently.

The way for me to have my highest standard of living would be to focus on writing, and buy everything else from other most bests.

If everyone else is also focusing on their most bests, and then trading for everything else, we all enjoy a higher standard of living. We each make more money by doing what we’re good at, and buying whatever else we need from others who can supply those things at a higher level of quality and lower cost than we ever could do ourselves.

Comparative advantage tells me that it would be dumb for me to put up a personal trade barrier, and try to make everything I need in-house. I’d spend less time and resources on the thing that makes me the most money, so my income would go down – and I’d spend more time and resources making stuff I’m not good at, which means that stuff becomes expensive and lower-quality to me.

“A free movement of labor allows us to become more efficient, produce better products at lower costs, grow more profitable, pay more taxes to the government, which, in turn, looks after the people who are displaced,” Ellison said at the time.

This isn’t a political argument. Ricardo’s concept of comparative advantage has been studied, repeated and updated by economists over the past 200 years. The overall consensus is that it is correct.

Yet there’s also a recognition that comparative advantage does cause pain for some people. When trade is free around the world, it’s important for individuals to be a part of a most best – or they get screwed.

So, if you’re working in an American factory and China or Mexico becomes the most best at making that same thing, you’ve got a problem. That factory is going to close. On the other hand, if you’re starting a tech company in Europe, and Silicon Valley is the most best at starting and scaling tech companies, your European company’s chances of success are limited. The U.S. techies will win.

In that way, it’s not hard to see why people left out of a most best might be supportive of Trump and his trade war. Even if comparative advantage is making the whole U.S. wealthier, individuals left out of most-best sectors are watching their jobs disappear or wages stagnate.

Yet protecting those jobs comes with a risk. As Ricardo might predict, trade isolationism would likely mean that instead of being most best at a lot of things and buying everything else from other countries, America may eventually produce all it needs for itself – but then it will become just OK at everything and most best at nothing.

—

This is my column as it ran in USA Today on February 4, 2004. It’s available through Newspapers.com.

March 19, 2025

The US and Russia Could Have Been Real Friends

While fishing around in an old jewelry box yesterday, I found a cache of lapel pins that I’d saved in the late-1980s. They tell a small story of a very different time in the relationship between the United States and Russia.

Back then, I was a young journalist at USA Today – a newspaper barely half a decade old. I was fascinated with news about Mikhail Gorbachev and the “perestroika” reform movement in the USSR. So, in 1987 I volunteered to travel there to report on how things were changing, especially in business and the economy.

Until that point, the USSR had been our Cold War enemy. Only a few US companies did business with the Soviets. Private enterprise was outlawed. The country had state-owned businesses and a black market, and nothing in between. Hardly any Americans traveled there, and if you did, you had to stay in one of a handful of hotels dedicated for Westerners. Credit cards only worked in those hotels or scattered “hard currency” stores that priced goods in dollars – and locals weren’t allowed into those. Once you were inside the Soviet Union, it would be a small miracle if you could make a phone call back to the US. Only a few phone lines led out of the country.

Preparing for my first trip there, at age 27, felt daunting. I had gotten to know some Americans who studied the Soviet Union, and I asked them what to bring to help me get around and break the ice at meetings. I learned that I should bring two kinds of effective “currency”: Marlboro cigarettes, and lapel pins that had something American on them.

Trading pins with newfound foreign friends was a thing in the USSR. A pin handed to a customs agent could prevent a search of your bag. A pin could turn a minor official from dour to affable. A pin could pay for a taxi ride.

Well, in 1987, USA Today had made up a boatload of five-year anniversary pins. Handily, they had “USA” on them. I packed a couple of fistfuls in my bag.

Before the trip, I was put in touch with a young Muscovite named Peter Zapolnov. He spoke English and worked for a Western entity that was starting – amid the political thaw – to import Western newspapers into the USSR. He was going to be my translator, guide and driver.

When I landed at Moscow’s then-shitty airport, Peter was waiting – inside the arrivals area, pre-customs. He walked with me to customs, where a young customs agent, confronted with a rare American visitor, seemed ready to give me a hard time. Peter asked me if I had an American pin with me. I said I did. Peter told me to give it to the agent. I did. The agent grinned widely and waved me through.

One of my main missions on that first trip was to cover a first-ever trade show of American consumer goods in the Soviet Union. In a vast hall in Moscow, companies such as Procter & Gamble set up booths giving locals their first glimpse of made-in-the-USA stuff ranging from deodorant to candy. And everywhere there were pins. The most popular, worn by both American and Soviet attendees, was a metal pin showing side-by-side US and USSR flags.

It can be hard to remember how radical that seemed. It was so optimistic. The pins were a symbol of a budding friendship between two countries that had been estranged from and angry at each other for 40 years.

The pins were also, significantly, a sign of what many Soviets wanted their country to become: more like America.

Soviet citizens were getting a taste of capitalism, and they liked it. They were getting a whiff of free speech, and they liked it. Over the next few years, as the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet empire crumbled, it seemed that Western civilization had won – not through war, but by being the better system. Eastern Europe and Russia opened their borders and their arms. McDonald’s opened in Moscow. Russian tech startups caught the eye of American investors. Real peace and cooperation seemed possible.

It didn’t last, of course. The transition turned chaotic and lawless. In a power vacuum, Vladimir Putin took charge. Russia didn’t go all the way back to its Soviet-style system, but it turned inward and once again squared off against the West.

Now here we are. The Trump Administration seems to want a new era of friendship between the US and Russia – an era that might invite pins showing US and Russian flags united.

But this feels different. The West has not won. It seems to be losing. The friendship doesn’t have the feel of optimism and openness. It feels cynical and transactional.

My pin once made me happy. Now it seems old-fashioned and naive. What could have been…didn’t happen.

–

If you’re interested in what life was like in Moscow as the Soviet Union came apart and its citizens first tried capitalism, please pick up my novel “Red Bottom Line.” It’s based on my reporting at the time, and is set in Moscow in 1991. As reviewers have noted, it’s a funny and satirical tale along the lines of movies like “Thank You for Smoking” and “The Death of Stalin.”