The Secrets of Illustrating Bug Beauties in the 17th Century

—This is a guest post by Cindy Connelly Ryan, a preservation science specialist in the Preservation Research and Testing Division, and Jessica Fries-Gaither, an Albert Einstein distinguished educator fellow at the Library. It also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

Would you raise insects in your kitchen? Travel thousands of miles from home to study them?

Maria Sibylla Merian, a 17th-century natural scientist, artist and engraver, did just that and broke new ground in science and art.Born in Germany in 1647 and later a resident of the Netherlands, Merian raised the larvae of caterpillars, butterflies and moths, determined their preferred food plants and observed adults emerging from their pupal chrysalides and cocoons. Her detailed notes and sketches became the basis for several groundbreaking books on caterpillars. She pioneered scientific illustration techniques by using counterproof printing to create softer images that more closely resembled her original drawings. She published De Europischen Insecten, and the Library preserves a copy of that book, now more than 300 years old.

In 1699, the intrepid Merian and her youngest daughter journeyed to the Dutch colony of Suriname in South America to study and paint insects. Back home, she published a book in 1705 — Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (Metamorphosis of Surinamese Insects) — that featured vibrant color illustrations of exotic species.

Recent analysis by scientists in the Library’s Preservation Research and Testing Division revealed details about how the book’s colors were created. X-ray fluorescence provided elemental “fingerprints” of materials, and reflectance spectroscopy captured chemical bonds’ visible and near-infrared absorption features. Multiband microscopy revealed details of the paints’ textures, layering and application techniques.

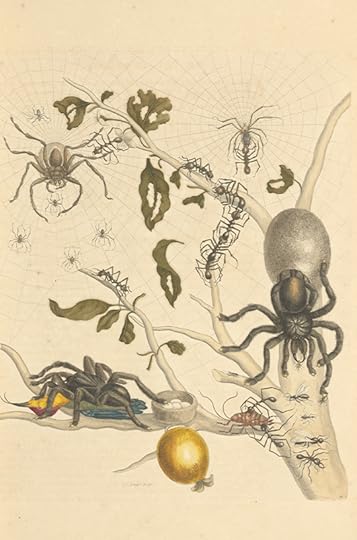

Merian’s artwork, here of spiders, gained her lasting fame. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.

Merian’s artwork, here of spiders, gained her lasting fame. Rare Book and Special Collections Division.The red cherries are rendered with the poisonous pigment vermilion applied in matte and glossy layers to model depth. The caterpillar hungrily advancing up the branch is rendered in at least eight shades of yellow, gold, orange and red, all made from mixtures of just two pigments.

The colorants were created with a combina tion of European and imported raw materials. Butterflies get their blue colors from thin layers of azurite, a mineral mined in Hungary and Germany. Translucent pink and burgundy tones come from brazilwood, a South American tree first used by European artists in the early 1600s.

In this way, modern science sheds new light on centuries-old science and art.

Subscribe to the blog— it’s free!

Library of Congress's Blog

- Library of Congress's profile

- 74 followers