Recriminations Fail

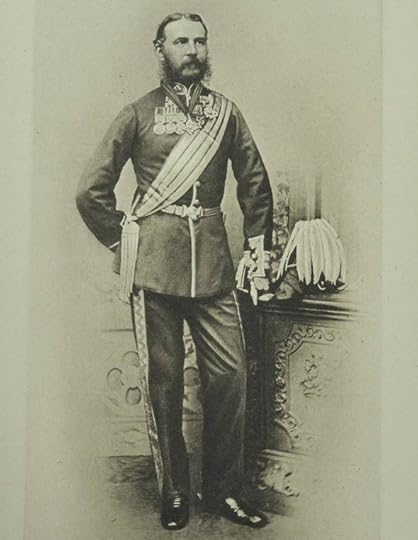

Sir Robert Walpole

Sir Robert WalpoleWalpole’s defeat at Ruiya did not go unnoticed. His account of the affair raised eyebrows throughout the military establishment. It garnered a cold response from Sir Colin Campbell and an even colder one from the office of Lord Canning, who heaped honour on Adrian Hope and carefully avoided any praise of Walpole.

No. 38.

No. 102 of 1858.

THE Right Honorable the Governor-General of India is pleased to direct the publication of the following despatch, from the Deputy Adjutant- General of the Army, No. 257 A, dated 20th April, 1858, forwarding copy of a report from Brigadier-General R. Walpole, Commanding Field Force, detailing his operations against and capture of the fort of Rooya, on the 15th instant.

His Lordship participates in the grief expressed by His Excellency the Commander-in-Chief at the heavy loss which the British army has sustained in the death of that most admirable officer, Brigadier the Honourable A. Hope, whose very brilliant services he had had the gratification of publicly recognizing in all the operations for the relief and the final capture of Lucknow. No more mournful duty has fallen upon the Governor-General in the course of the present contest than that of recording the premature death of this distinguished young commander.

The Governor-General shares also in the regret of the Commander-in-Chief at the severe loss of valuable lives which has attended the operations against the fort of Rooya.

R.J H. BIRCH, Colonel, Secretary, Government of India, Military Department, with the Governor-General.

Walpole’s dispatch was rightly seen by many as suspicious, neglecting outright to mention he had been strenuously advised to reconnoitre by not only Brind but Haggart and Hope. He had dismissed outright the information given to him by the trooper of Hodson’s Horse, who had no reason to lie, in favour of two guides who most likely had every reason to lead him astray. To make matters worse, Walpole had not made use of his artillery, his engineers or his sappers. When under fire, he had been unable to make clear decisions, had acted irrationally and with anger, and, above all, had failed to listen to the very men who could have won him an astonishingly easy victory.

As it turned out, the next morning, when the British entered Ruiya Fort, it was even clear to the regimental surgeon of the 93rd, Munro, just how simple the task would have been. The south side of the fort had no defences at all except for a narrow grove of trees, a shallow and practically empty ditch, and a low, broken wall. It was, in fact, so open that the cavalry could have ridden in and taken care of the operation themselves. To make matters worse, James Hills-Jones (VC), who happened to be present with Tombs’ battery, had seen Nirpat Singh’s horsemen riding in and out of the place during the entire battle. This was corroborated by another officer, Sam Browne (later General Sir Samuel James Browne, VC, GCB, KCSI). He had taken it on himself to reconnoitre the fort early the next morning with his cavalry and found a breach in the wall so wide his regiment could have ridden in “three abreast.” Adrian Hope and the others had lost their lives for nothing. As William Russell, the Times correspondent, accurately pointed out, “Walpole seems to have made the attack in a very careless, unsoldierly way…”

The condemnation was severe, and although this particular passage was written 20 years after the fact, it reflected the thoughts and feelings of many who served under Robert Walpole. The campaign, as Malleson rightly pointed out, was not a difficult one and very little was asked of Walpole. “To carry it to a successful issue, then, demanded no more than the exercise of vigilance, of energy, of daring—qualities the absence of which from a man’s character would stamp him as unfit to be a soldier.

Walpole, unhappily, possessed none of these qualities. Of his personal courage, no one ever doubted, but as a commander, he was slow, hesitating, and timid. With some men, the power to command an army is innate. Others can never gain it. To this last class belonged Walpole.

He never was, he never could have been, a general more than in name. Not understanding war, and yet having to wage it, he carried it on in a blundering and haphazard manner, galling to the real soldiers who served under him, detrimental to the interests committed to his charge. If the campaign offered no difficulties, it may be urged, surely any man, even a Walpole, might have carried it to a successful issue. Thus, to brand a commander with incapacity when the occasion did not require capacity is as unnecessary as ungenerous!

It might be so, indeed, if the campaign, devoid of difficulty as it was, had not been productive to of disaster. But the course of this history will show that, that though there ought to have been no difficulties, Walpole, by his blundering and obstinacy, created them, and, worse than all, he, by a most unnecessary — I might justly say by a wanton — display of those qualities sacrificed the life of one of the noblest soldiers in the British army — sent to his last home, in the prime of his splendid manhood, in the enjoyment of the devotion of his men, of the love of his friends, of the admiration and well-placed confidence of the army serving in India, the noble, the chivalrous, the high-minded Adrian Hope.“

The censure of Robert Walpole was loudest in his own camp. The dispatch had been humiliating for the 4th Punjabis, who, having fought valiantly at Delhi and the Lucknow campaign, now stood accused of being unwilling to follow orders. Besides this, their well-respected captain, William Cafe, was severely wounded, and young Edward Willoughby, whose brother had blown up the Delhi Magazine in May 1857, was dead. The retreat had been so sudden the Punjabis had been unable to collect all their dead and wounded from the field, which was strongly against their principles. To make matters worse, the next morning, just before the Punjabis returned to Ruiya, one of the men, who had been left for dead, crawled into camp and told them a ghastly story. As soon as Walpole had vanished, Singh’s men had poured out of the fort, carrying lanterns, intent on plundering the dead and killing anyone who was still alive. He had tried to play dead, but “when a man was trying to turn him over, he suddenly grappled him, wrenched the sword from him and killed him. Then, with much difficulty, for he was wounded in the thigh, managed to get out of the ditch and crawled painfully after the Regiment. The story had the worst effect on the men for it was a maxim of Wilde’s never to leave a wounded man to be cut up by the enemy, even at the sacrifice of many lives.” When they returned, they found the dead had been horribly and insultingly mutilated. They had also lost their favourite and highly respected Indian officer, Subedar Major Hira Singh. While the Europeans buried their dead, the Sikhs cremated his remains with every military and religious honour they could. Like Hope, Singh had been shot through the neck by a man sitting in a tree.

The 4th Punjabis lost all of their most senior officers in the affair at Ruiya and would continue their march commanded by Lieutenant Stewart with Lieutenant Stafford and Hawkins under him – the latter had but recently joined. It seemed to Surgeon Fairweather, who had seen his Regiment suffer so much for so little gain, that their once proud spirit was broken. The men confided in Fairweather that they felt they were being expended for no good reason, and they would never see their homes in the Punjab again. They had marched to the siege of Delhi in 1857 with twelve officers and eight hundred men, and now there were only 109 of the original contingent left.

In the ranks of the 42nd and the 93rd, dislike of Walpole boiled over into pure hatred. For these same regiments that had climbed the Alma together (and the 93rd that formed Campbell’s Thin Red Line) had been ordered to retire, a humiliation they were hardly likely to forgive Walpole for. At the funeral on the 16th, the atmosphere was so bad that the officers were worried they would have a mutiny on their hands. To make matters worse, when the 93rd’s sentries reported that Nirpat Singh was leaving the fort, and indeed had passed only a few hundred yards in front of them, General Walpole ignored their reports, and they were told to desist from disturbing the camp any further. An enraged Lieutenant Gordon-Alexander had to be prevented by clearer heads than his from ordering his picket of 60 men, two guns and a few Sikh horsemen to march straight back to Ruiya and take the fort that very night themselves. Out of sheer insolence, the saying “Tull ye tak’ Ruiya” for any order that was issued in haste was prevalent in camp, and the men took to calling the fort “Walpole’s Castle”. Wisely, Walpole avoided direct confrontation with the rank and file as much as possible. Surgeon Fairweather believed the Highlanders would have liked nothing better than to shoot Walpole dead, and rightly surmised Hope and the others had been done to death by the “mismanagement of an arrogant nincompoop.” At Hope’s funeral, the officers had even expected the troops to rise in mutiny.

The problem was, they would have to fight for him again.

Sirsa, 22 April 1858The force marched on 18 April, and much to the immense irritation of the surgeons, it looked like camping on open plains was once again on the menu. After a few more men collapsed from the heat, Munro ignored Walpole’s directive and ordered the 93rd to set up their tents in a grove of trees; they were quickly followed by the other regiments. Walpole decided this was not the time to object, and he let this piece of obvious insubordination pass by without a word. At this point, no one really cared if he boiled his head.

After five marches, on 22 April, they reached a strong village on the right side of the Ramganga, named Sirsa, only seven miles from Aliganj. The cavalry of the advanced guard reported back that they had made contact with a rebel picket that was in the process of retreating. Walpole was loath at this point to make any attack on the rebels retreating or otherwise, but after some persuasion for Haggart and Brind convinced him that an attack could be carried out with little loss, provided they were allowed to manage it.

Major General Sir Henry Tombs VC KCB

Major General Sir Henry Tombs VC KCB

“The column was halted, in order that the heavy gun might be brought to the front and the infantry close up. The horse artillery and the cavalry, however, went ahead. When about a thousand yards from the largest village, the enemy opened fire with their six guns and sent their shot and shell among them. On they galloped together, for it was Tombs’ proud boast that his light guns could go wherever the cavalry could go. Six hundred yards from the village, they drew rein. The 6 – pounders quickly came into action, and the rebel fire slackened. The troop of 9 -pounders, retarded by the broken and difficult ground, came up, and soon silenced the united tearing fire of the enemy’s guns, and drove their infantry from the village and the shelter of the trees. Their cavalry showed a bold front, in the hope of saving their guns, which were being slowly dragged away by bullocks, but a flank movement and the advance of the infantry disconcerted them, and they fled. The pursuit was conducted with such vigour by the cavalry and artillery that the enemy’s camp was captured.“

This time, Walpole was prudent with the use of his infantry, whom he kept well in reserve, ensuring this time, they did not fight at all. While Sirsa was seen as a small victory, the men in his camp were cognisant of the fact that Walpole did not carry it through, and most of the rebels escaped to join their compatriots at Bareilly.

“The infantry was formed up accordingly, with the 79th Highlanders leading in line, supported by the 4th Panjabis , the 42nd and 93rd Highlanders following in line of contiguous columns in reserve. Walpole’s bad generalship showed itself again by allowing the infantry brigade to be hurried across the ploughed fields for nearly four miles at a run, in a foolish endeavour to keep up with the cavalry, under that awful sun…It was reported in camp that evening that it was only on the urgent representations of Brigadier Haggart, 9th Lancers, commanding the cavalry, that our pig- headed General allowed him to follow the retreating foe up, with the result that the Horse Artillery and cavalry captured the village before we of the infantry could overtake them.”

The only satisfaction that the infantry had after this was when the cavalry reported that many of the men they had cut up had belonged to Nirpat Singh, so in a sense, it was a vengeful victory after all. The remainder of the rebel force left their baggage behind, and the cavalry captured four guns. They retreated on this occasion in such a hurry that they neglected to destroy the bridge over the river, and Walpole could now move his guns and column closer to Aliganj without worry. The same day as he took Sirsa, the force continued its march towards Aliganj and encamped one mile outside the town. Here they remained until 27 April, when they were joined by Sir Colin Campbell.

Colonel Walpole is not censured

Colonel Walpole is not censuredIf the Highland Regiments expected Sir Colin Campbell to tar and feather Walpole, in this instance, his famous temper let them down. Instead, he let Walpole off, and much of this had to do with Walpole’s dispatch. He had stated officially that the infantry “had gone much nearer to the fort than I wished or intended them to go,” and Sir Colin Campbell concurred that his difficulty was not so much down to poor leadership and bad management but the temper of the Highlanders.

“The difficulty with these troops … is to keep them back; that’s the danger with them. They will get too far forward.” Sir Colin would later allude to the Ruiya affair and to the“rashness of officers in a subordinate position attempting to blame or judge the act of their superiors, of the strength of those mud forts, and of the difficulty of restraining their Highlanders.” He did not take into account either the reports of Brind or Haggart, and above all, he disregarded the Highlanders themselves.

“As was Sir Colin’s wont, especially since he had been gazetted to the Colonelcy of the 93rd Highlanders, he visited our lines in the evening, commencing with a stroll amongst the men’s tents, addressing men he knew by name, and asking how they were; but he received short and rather surly answers, such as, ‘Nane the better for being awa frae you, Sir Colin; or, ‘As weel as maun be wi’ a chiel like Walpole,’ till, the news spreading that Sir Colin was among the tents, all the men turned out and fairly shouted at him, ‘Hoo about Walpole?’ – meaning, what was he going to do with Walpole after that terrible Ruiya business. Sir Colin was evidently much disconcerted (for the commotion in camp brought me to my tent – door, and I myself saw and heard what I have above described), and, instead of going on to the mess tent, went straight back to his own camp, and until after the battle of Bareli not only did not come near our lines again, but took no notice of the regiment when riding past us with his staff on the line of march .” (Alexander)

This certainly matches what William Russell had to say about Walpole, when writing on the 27th – “His manners are unpleasant, and he has managed to make himself unpopular. It would be impossible to give an idea of the violent way in which some officers spoke of him today.” Even Russell expected Walpole would at least receive a dressing down, but nothing of the sort happened. Sir Colin Campbell interceded on Walpole’s behalf, not only with the officers under his command but with Lord Canning, who was fretting about what to do with the man and lamenting the loss of Adrian Hope. His words must have been soothing, for Walpole was recommended for, and received a C.B. and later a K.C.B., and from Sir Colin Campbell, the command of the Bareilly division. It was seemingly enough that Sir Colin Campbell trusted and believed in Walpole as a leader for those who had authority, to overlook the senseless slaughter at Ruiya. That Sir Colin Campbell could not look his favoured 93rd in the eye, however, tells another story in itself.

As Malleson writes:

“It is a curious commentary on the principle then, now in fashion, of conferring honours on men, for the deeds they achieve, but for the high positions they occupy, that the general who lost more than one hundred men and Adrian Hope, in failing to take this petty fort, was made a KCB. Though he failed to take the fort, he was yet a divisional commander.”

Malleson was alluding here to Walpole’s influential background – his mother was the youngest daughter of the 2nd Earl of Egmont and sister of Prime Minister Spencer Perceval – the only British prime minister ever to be assassinated. His grandfather was Thomas Walpole, who himself was the son of an eminent diplomat, Horatio Walpole, 1st Baron Walpole, who happened to be the younger brother of Robert Walpole, the first Prime Minister of Great Britain. It is no wonder that no one was willing to give this Robert Walpole a rebuke, not even Sir Colin Campbell.

Following Bareilly, Walpole was left in command of the Rohilkhand division until 1860. Before the mutiny was completely extinguished, he would have one more fight, on the Sarda River, where he did shine through as a leader of a small force in a skirmish. For his mutiny services, Walpole received the Mutiny Medal with one clasp for Lucknow; by the home authorities, he was first made Companion and then Knight Companion of the Order of the Bath (military division) and received thanks from Parliament. In 1861, he took command of the Lucknow Division, but it was a short posting, for in the same year, Walpole was transferred to Gibraltar to command the infantry division. Promoted to major general in 1862, he returned to England two years later to command the Chatham Military District, a position he stepped down from in 1866, upon being given a colonelcy of HM’s 65th Regiment of Foot. Promoted to Lieutenant-General in 1871, Sir Robert Walpole died on 12 July 1876 at the Grove, West Molesey, Surrey.

The Dictionary of National Biography very carefully worded its assessment of Walpole, disregarding quite blatantly what was known about Ruiya:

“Walpole’s conduct of this operation has been severely censured, and Malleson, in his ‘History of the Indian Mutiny,’ not only asserts that the second in command, Brigadier Adrian Hope, who was killed in the attack, had no confidence in his chief, but that Walpole was altogether incompetent as a general in command. There is no evidence for either of these assertions; Walpole was not a great commander, but the strictures passed upon him were undeserved. On the occasion in question, Walpole undervalued his enemy, and in consequence many valuable lives were lost; but the commander-in-chief was fully cognisant of all that took place, and, so far from withdrawing from Walpole his confidence, he continued to employ him in positions of trust and in important commands.”

We shall now turn away from Sir Robert Walpole and give our attention to the heroes of Ruiya, who justly deserve their honours.

Sources:

Behan, T. L. – Bulletins & Other State Intelligence for the Year 1858 – Part III (London Gazette Office, Harrison & Sons, 1860)

Gordon-Alexander, Lieut. Col. W. – Recollections of a Highland Subaltern (London: Edward Arnold, 1898)

Malleson, Col. G.B. – History of the Indian Mutiny, Vol. II (London: William H. Allen & Co., 1879)

Munro, Surgeon-General – Reminiscences of Military Service with the 93rd Highlanders ( London: Hurst & Blackett Publishers, 1883)

Munro, Surgeon General – Records of Service and Campaigning in Many Lands, Vol II (London: Hurst & Blackett Ltd., 1887)

Russell, William Howard– My Diary in India, Vol. I (London: Routledge, Warne & Routledge, 1860)

Walford, Edward (1864). The County Families of the United Kingdom, Or Royal Manual of the Titled and Untitled Aristocracy of Great Britain and Ireland. 2. Ed. Greatly Enl. Hardwicke.

Vetch, Robert (1899). “Walpole, Robert (1808-1876)”. Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 59. (London: Smith, Elder & Co.) p. 207.

Wright, William – Through the Indian Mutiny – The Memoirs of James Fairweather, 4th Punjab Native Infantry, 1857-58 (Spellmount Military Memoirs, 2011)