Walpole Blunders

The “mixed stars” mentioned in the previous post, “The Lay of Land”, would begin to show their bad disposition early on in Sir Colin Campbell’s Rohilkhand Campaign. Like with the appointment of Windham for the defence of Cawnpore, and Mansfield during the final battle to retake the city on 6 December 1857, Sir Colin once again placed his trust in a man who, though showing much promise at first, had little business leading a column.

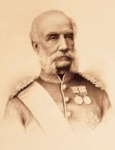

Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Walpole, KCB

Lieutenant-General Sir Robert Walpole, KCB Robert Walpole was born in 1808, the son of Thomas Walpole, a British diplomat and his wife, Lady Margaret Perceval, the eighth daughter of the 2nd Earl of Egmont. Educated at Dr Goodenough’s school in Ealing and at Eaton College, Robert received a commission in the Rifle Brigade in 1825 – his first posting, however, was not India, for his regiment at the time was in Nova Scotia. His career, indeed, had no connection with India at all – Walpole served with his regiment in England, Ireland, Jersey and Malta. Rising through the ranks, Walpole was promoted to lieutenant-colonel in 1847 and to the staff of the deputy adjutant and quartermaster general while in Corfu. In 1854, he was promoted to colonel and remained in Corfu for another two years.

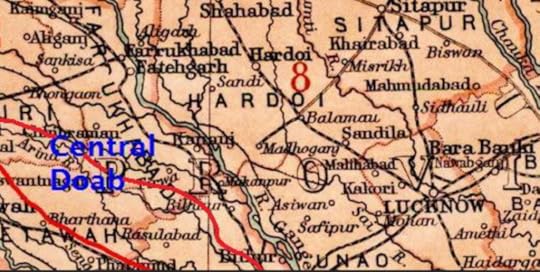

In 1857, Walpole and the Rifle Brigade set sail for India, arriving in Cawnpore in early November. He would not participate in the evacuation of Lucknow but would remain behind with Brigadier Windham to follow Campbell’s orders of ostensibly keeping Cawnpore safe. As we have seen, things did not go quite to plan; however, it was Windham whom Campbell censured for the near-disaster at Cawnpore. Walpole, who, on 28 November, had indeed defeated an attack of the Gwalior Contingent and captured two 18-pounder guns, was rightly praised for his work. On 6 December, Walpole commanded a brigade during the Battle of Cawnpore; then on 18 December, he led a detached corps through the Doab, capturing Etawah on the 29th. On 3 January 1858, they had reached Bewar, where Walpole took command of Colonel Thomas Seaton’s force, joining Campbell at Fatehgarh the next day. Upon the formation of the Army of Oudh, Walpole was once again at the forefront, commanding the third division (5th and 6th Brigades). With the Dilkusha taken on 6 March, Brigadier General Walpole, together with Sir James Outram, crossed the Gomti to take the rebel positions in the reverse.

Until now, Walpole had not given anyone cause for concern. He followed orders, was neither overly loved nor universally despised and a steady officer.

On 7 April 1858, Colonel Walpole left Lucknow in command of his own division. It was certainly an illustrious one, consisting of 4000 fighting men:

Cavalry

9th Lancers

2nd Punjab Cavalry

Brigadier Haggart, 9th, commanding

Infantry

42nd Highlanders

79th Highlanders

93rd Highlanders

4th Punjab Rifles

Brigadier Adrian Hope, 93rd, commanding

Artillery

2/1 Bengal Horse Artillery (Capt. & Brev.-Lt. Col. H. Tombs, VC)

3/3 Bengal Horse Artillery (Capt. ( Brev.- Lt. Col. F. F. Remmington)

Detachment 1/5 Bengal Artillery (Lt. E.W.E. Walker)

4/1 Bengal Artillery (Captain H. Francis)

Two 18-pounders

Two 8-inch howitzers

Two 8-inch mortars

Two 5 1/2 -inch mortars

Major J. Brind, Bengal Artillery, commanding

23rd Company, Royal Engineers, detachment of Bengal Sappers and Miners

The task before Walpole, though difficult, was not considered one that would severely test the qualities of a commander. While he might need to dismantle a fort or two and disperse handfuls of disorganised rebels or quell a recalcitrant talukdar and his band of matchlock men, Sir Colin Campbell was quite sure a man of Walpole’s abilities would be able to tackle such problems. He had no major rebel force in his path, and his orders were simply to “advance up the left bank of the Ganges, and so to penetrate into Rohilkhand.” He was, according to his orders, to march to Aliganj, and there wait for Sir Colin Campbell and on “no account to seek the enemy, or turn to the right or left to undertake any operation.” While the march itself would take some three weeks to accomplish, Sir Colin Campbell did not anticipate that Walpole would face any resistance, and his orders were very clear.

The men of the 93rd Highlanders were tossed out of their beds in Lucknow at 3 am on 7 April, for a 5 am march; however, they only moved 9 miles from the Dilkusha to the Musa Bagh, where they were ordered to halt at 8 in the morning. For some unexplainable reason, their baggage did not arrive for another five hours, when, for reasons again unknown to anyone, they were ordered to move another two miles down the road, “and, although there was enough shade in the neighbourhood to shelter an army of 10,000 men, we had to pitch our tents out in the open, under a sun with which you could cook a beefsteak on a flat stone! The tents were not pitched till past two o’clock, when we retired to their shade with the thermometer at 140 °!”

While Alexander and the 93rd grumbled, the plain slowly filled up with the other corps who were joining them in Walpole’s division – until late in the day, they marched in, one after the other, from their various posts around Lucknow and early on 9 April, the division moved out.

There were no prepared or metalled roads to speak of between Lucknow and Aliganj, and the division moved cross-country over sandy tracks, often intersected by dry water courses. They moved on in a north-westerly direction through a land bereft of both shade and mutineers. For the next seven days, they marched in what could only be described as the bowels of hell, for Walpole now showed himself as a most terrible manager.

Instead of taking advantage of the night hours, as most experienced, sensible commanders were wont to do in Indian summers, he never managed to issue his orders for the next day before midnight, and the marches commenced, not at any regular time but whenever it seemed to appeal to Walpole. It was 3 am one day, but 5 am the next, and perhaps 4 on the day after that, but by the time everything was packed and ready, there were hardly any night hours left and the force, though Walpole kept their marches short to no more than 9 miles a day, by the time they reached their camping ground, it was in the full blaze of an Indian sun and hours to wait until they could crawl under canvas. Walpole appeared to have fostered a particular fear of trees for his force was inevitably ordered to encamp on the open plain, “under a sun which generally registered on the thermometer 140 ° or more whilst we were pitching our tents, and never less than 108° for the day, when we got into them, whilst we were surrounded by magnificent groves of mango-trees capable of sheltering five times as large a force as ours, and there were no military reasons for our not taking advantage of them.”

The heat made sleep impossible during the day and the night was no better; the tents were pitched close next to each other, surrounded by the sounds and smells of camp life – “for the shrill trumpeting of elephants, the infernal noise made by the camels which were kneeling close round our tents in scores, the horrible effluvium emitted from their bodies, the constant monotonous crunching, grind noise made by them as they chewed the cud…” The heat verily radiated off the ground, leaving the army sleepless, restless and after a few days of this treatment, exhausted. The next day, at whatever time Walpole chose, they would stagger to their feet and face another gruelling march. It was no surprise that the first casualties in Walpole’s force did not fall to the bullet, but to sunstroke and heat apoplexy.

The Highlanders were possibly worse off than anyone else, for no one had considered that their heavy dress (full Highland dress) was unsuitable for an Indian summer. There would have been enough time in Lucknow to fit them up in lighter clothing, but here they were, marching on a grilling plain, wearing wool. “Their cries for water were incessant – no jest or laughter was heard, they were too weary and life at the time too uncertain, for every now and then, as we moved silently and listlessly along, a comrade would stumble in the ranks, and, without further warning, fall to the ground, smitten down by heat apoplexy.”

At the latest, after the third day of such misery, Walpole should have realised he was marching his army to their deaths, but he continued on with his strange ideas, and camping out in the open, oblivious not only to the protests of tried India hands from the Bengal artillery and the cavalry, but the regimental surgeons.

While this certainly pointed to poor leadership, the men would soon see worse.

93rd (Sutherland Highlanders), NCOs, in India 1864, with more suitable uniformsThe Battle That Should Not Have Been – RUiya

93rd (Sutherland Highlanders), NCOs, in India 1864, with more suitable uniformsThe Battle That Should Not Have Been – RUiyaSituated two miles from Madhoganj, fifty miles from Lucknow, (or more accurately, fifty-one

miles west by north from Lakhnao, and ten miles east of the Ganges– Malleson) stood the fort of Ruiya, the ancestral holding of a petty landowner, Nirpat Singh.

Singh was a rebel, “as long as rebellion seemed profitable,” but he had never taken an active stand against the British. Loot and plunder were more his style, and he took advantage of the surrounding chaos to start arguments with his neighbours. In April 1858, he was neither amassing an army nor actively picking a fight with the British. It would be Walpole, however, who would bring the contest to him.

The Council of War – of Sorts

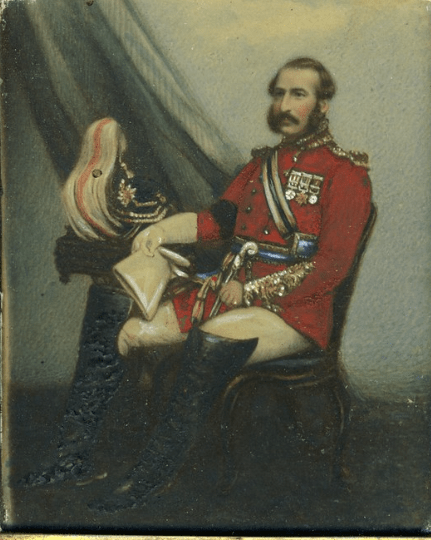

Colonel James Brind

Colonel James BrindOn 14 April, Walpole’s spies informed the general that Ruiya was not only occupied by rebels, but Nirpat Singh was planning to attack the column; they further exaggerated the numbers of his supposed force, driving it up from the actual 300 to the fantastical figure of 1500. No attempt was made to confirm that this was actually true, and being an officer with little Indian experience, Walpole did not feel inclined to question the veracity of the statement. Among his advisors, accompanying the force as civilian magistrate, was Captain Thurburn, a man of considerable experience (as we have already seen), who felt disinclined to accept such vague information; he further wanted Walpole to listen to what another informant had to say.

A trooper of Hodson’s Horse had, some weeks back, been captured by Nirpat Singh’s men and held in Ruiya Fort – the very morning Walpole arrived at Madhoganj, the trooper had managed his escape and had made his way straight to Walpole’s camp – it is unclear whether his escape was by design or by chance, but at any rate, his information was certainly worthy of mention. He informed Walpole, through Thurburn, that Nirpat Singh had no intention of fighting the British, yet he needed to save face in front of his people. He would oblige them by making a show of resistance, just sufficient to save his honour and then, when this was accomplished, he would evacuate Ruiya and leave the gate open for the British to walk in. Thurburn should have, at this point, insisted that Walpole listen to the trooper; he could have intervened and explained that this was not an unusual way of doing business in India; had he had any powers of persuasion, he might have prevented Walpole from attacking Ruiya at all. Instead, Walpole appears to have only half-listened to what Thurburn said. Information was abroad that Begum Hazrat Mahal had indeed been in touch with Nirpat Singh, and there was certainly a possibility he was hostile to the Government, but the statement of the trooper should have been given careful consideration. Besides this, after the Oudh Proclamation, Singh stood more to lose from an encounter with the British than Walpole stood to gain.

Captain Thurburn

Captain ThurburnWalpole, however, refused give the trooper’s story any credit, nor did he bother to set up any communication with Nirpat Singh. In Walpole’s mind, the thought of winning his spurs against a fort of 1500 heavily armed rebels in a jungle fort was more appealing than using common sense. Then came the problem of sound military practices.

“The slightest examination would have shown him that whilst the northern and eastern faces were strong, covered by dense underwood and trees, the western and southern were weak and incapable of offering defence. These faces were approached by a large sheet of water, everywhere very shallow, and in many places dried into the ground, and the walls here were so low that an active man could jump over them…”

On the evening of the 14th, Walpole, after some persuasion by his DAAG Captain Carey, agreed to summon Brigadiers Hope and Haggart and Colonel Brind to his tent for something that could have been called a Council of War, had Walpole not already made up his mind. Without any ceremony, he informed them he intended to attack Ruiya Fort the next morning – the information he had received was sound regarding not only the fort but the road leading to it, as related by the native guides, whom he believed were honest and trustworthy. At daylight, the force would advance along a road leading to the left of Ruiya; this road split a couple of miles from the camp into two – one road then ran through supposed open country in the direction of the fort and the other to the village of Rowdamow. On reaching the junction in the road, Colonel James Brind was instructed to advance with the whole of the artillery and take up a position to fire at the fort, while the cavalry and infantry brigadiers were to follow and “act as circumstances might require.” Brind, a man of considerable experience and who had fought not just at Lucknow but through the Siege of Delhi, asked Walpole if his information was absolutely reliable and the country was indeed open as the guides intimated. Otherwise, he advised mounting a reconnaissance to the point where the road divided, before attempting to attack Ruiya. He further told Walpole that “under any circumstances his duty duty to his own Command, to the Force, to the General himself, to the Commander-in-Chief, and to the Government of India, made it imperative to a draw the General’s attention to the danger of advancing with the whole of the artillery without the support of the infantry, and without first reconnoitring the ground over which he was to move.”

Annoyed with Brind, Walpole turned on Haggart and Hope, asking if they held the same opinion – both men concurred. Seeing he had no choice, Walpole half-heartedly agreed that a reconnaissance would be carried out the following morning, by Captains Lennox and Maunsell of the Engineers.

The 15th of April

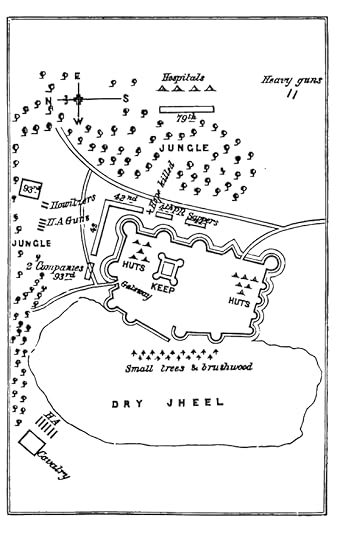

Fort Ruiya

Fort RuiyaThe next day, however, unprepared and completely convinced of his own self, Walpole ordered the men to march, under arms, toward Ruiya. The force began to move forward, and suddenly, contrary to Walpole’s belief of “open country,” they were faced with a wall of thick jungle. To the surprise of Brind, Hope and Haggart, Walpole determined to ignore any talk of reconnaissance at all, despite what had been agreed upon the night before, and ordered the whole of the artillery, with spare ammunition, to advance through the jungle towards the fort, the infantry following. The cavalry was to make a detour to the right and try to get around the rear of the fort – Brind immediately objected. He pointed out that the danger of taking the heavy guns and spare ammunition through an unknown jungle was not advisable and suggested instead to advance with the light guns instead, preceded and supported by the infantry; he also said the guides had already proved false and trusting them any further was folly. Brind suggested a method of ensuring the guides were not misled a second time – they should be, “induced to lead, with a bag of gold tied to their waists and a halter round their necks, and soldiers with loaded rifles on either side of them; explaining to them they should have the gold if faithful, be hanged if faithless and shot if they attempted to escape.”

For reasons known only to himself, Walpole refused to doubt the guides but “desired Colonel Brind to do what he pleased with his heavy guns, and to arrange with the Brigadier commanding the infantry for an escort to accompany his light guns through the jungle.” Accordingly, the heavy guns, baggage and spare ammunition were left parked in Madhoganj, as was Walpole’s fashion, on an open plain but at least under a guard of cavalry and infantry. Hope and Brind now proceeded with their arrangements.

Four Horse Artillery guns under Lieutenant-Colonel Harry Tombs would precede the skirmishers of the 42nd, to be followed by the main body of the regiment. Colonel Brind would lead, followed by a small detachment of breaching artillery, supported by the 93rd with the 79th and 4th Punjabis held in reserve. At the same time, the cavalry with one troop of Horse Artillery under Haggart would sweep around to the right to get as close to the fort as possible from the north-west.

After a considerable struggle to get through the jungle, the advance suddenly came to a halt, for quite unexpectedly, heavy firing opened from several small guns and matchlocks in the fort. If Walpole had listened to the trooper of Hodson’s Horse, he would have known this was Nirpat Singh making a show of things. It was still not too late to stop what would happen next, but as the artillery did not know Singh was making a sham attack and Walpole didn’t tell anyone, it looked like there would be a stiff fight ahead. He was also on the strongest side of the fort, and this would ultimately be his undoing. In his official report, Walpole states,

“The fort on the east and north side is almost surrounded with jungle, and at these two sides, the only two gates were stated to be, which information proved correct. It is a large oblong, with numerous circular bastions all round it, pierced for guns, and loopholed for musketry…” While he noted did cast a cursory glance at the west and south side, all he saw was “a piece of water, which was partially dried up.”

The southern wall, too, had a gate, scarcely defended, but this did not appear to shine in Walpole’s senses.

He continues, “A tolerable view of the fort having been obtained from the road which leads into it from the north, the heavy guns were brought up; the two 18-pounders were placed on it; the two 8-inch mortars behind a wood still further to the right.” He then ordered the infantry, in skirmishing order, to advance straight to the fort. The 42nd took up a position at the north-east angle of the fort on the slope of the glacis, not far from the ditch; two companies of the 93rd were sent to the right of the 42nd, and when the attack commenced, the 4th Punjabis to their left.

One can only imagine Nirpat Singh’s surprise when Walpole attacked him. He had intended to shoot off a few rounds and then, as promised, retreat, leaving Ruiya abandoned for Walpole’s taking. Instead, he saw the British general, who was obviously devoid of reason, sending his infantry in skirmishing order against the only defendable face of the fort. Nirpat Singh slammed the gates shut and was now determined to put up a fight, and the infantry would soon bear the brunt of Walpole’s folly.

Walpole sent two companies of the 42nd in skirmishing order, with no support, directly to the front. Nirpat Singh ordered his men to man the walls, and he further sent skirmishers to climb the numerous trees in the fort. Well hidden in their boughs, they were practically invisible to the advancing infantry and at considerable leisure to pick off their targets. When the infantry reached the fort they suddenly realised there was a ditch and they had no means of crossing it; meanwhile the fire from the loopholes increased in intensity –“The skirmishers still persevered, some of them even penetrated into the ditch; but their valour was useless, the enemy remained unseen, there was no breach, there were no ladders, and the hostile fire continued.” Captain Ross-Grove of the 42nd vainly called for scaling ladders; he received, instead, the 4th Punjabis. Captain Cafe quickly led his gallant regiment of five officers including the regimental surgeon and 105 men down through the jungle and across the glacis, taking up a position to the left of the 42nd only to find he had taken them directly into the line of fire – there was no cover for his men and the only sensible solution was to take them down into the ditch, as close to the walls as possible to escape at least the fire from the bastions. He could see there was no breach, not even a gap in the wall by which they could enter the fort and the only way they could reach the top of the wall (which was only nine feet high from the bottom of the ditch) would be “by pushing and helping each other up one at a time.” The Subadar Major and Captain Cafe managed to get up using this method and looked over the parapet of the wall – they quickly came to the conclusion that under such a heavy fire from the Singh’s men, in their tower, their trees and behind their loopholes, it would be impossible, without vigorous support, to assault the fort in such a manner. Cafe ordered the Punjabis to remain in the ditch while he sent back his report to Walpole, for which he never received an answer. After thirty of his men were killed or wounded, Cafe led the remainder out of the ditch and back to the original position behind the counterscarp, the 42nd on his left and a group of bewildered, orderless sappers on his right. Of the gallant deeds of the 4th Punjabis, we shall return later. However, Walpole mentions none of this in his official report, but to add a little salt into their wounds, would write,

“After a short time, a great many of the infantry were killed and wounded from having crept up too near the fort, from which the fire of rifles and matchlocks was heavy. These men had gone much nearer to the fort than I wished or intended, and some of the Punjab Rifles, with great courage but without orders, jumped into the ditch and were killed, endeavouring to get up the scarp.”

Alexander, of the 93rd, has his version, related to him by survivors of the horrible slaughter at the ditch:

“Walpole ordered two companies of the 42nd Highlanders to the front; they advanced through the brushwood in skirmishing order close up to the ditch, losing many men. Presently, Walpole ordered up the 4th Panjab Rifles to reinforce them; these aligned themselves on the left of the 42nd, and with the 42nd presently threw themselves into the ditch to escape, if possible, the biting fire from the loopholed walls, and they found no shelter, and being without ladders, could effect nothing against the enemy. In this death -trap the 42nd Highlanders lost 2 officers and 7 men killed, and 2 officers and 31 men wounded; and the 4th Panjabis 1 officer and 46 men killed and wounded, all shot down like dogs at 20 or 30 paces distance.“

Colonel Brind at least had not taken leave of his senses and, realising what was happening, ordered the Horse Artillery guns to an exposed position on the edge of the jungle, to fire over the heads of the advancing infantry, and “sweep with shot and shell the bastion and curtain opposite or rather under which the 42nd and the other corps lay, so as, if possible, to keep down the heavy and destructive matchlock fire of the enemy; at the same time, he directed Lieutenant Harrington (VC) to bring up two 18-pounders and two 8-inch howitzers and place them in a position on the eminence to the south-west of the Fort and to confine the fire of the heavy guns on one spot and open a breach as quickly as possible, believing it was the General’s intention to storm the place.”

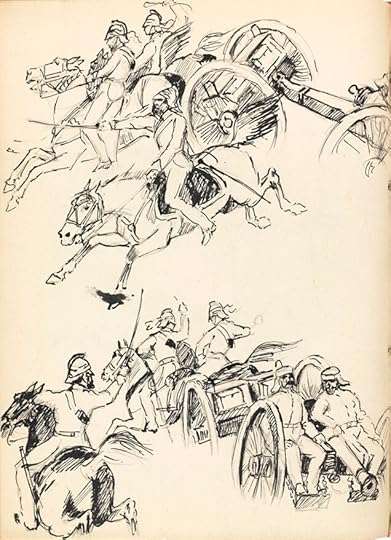

Bengal Horse Artillery, riding into action, drawing, Lt. Lawson

Bengal Horse Artillery, riding into action, drawing, Lt. LawsonWe must remember, Walpole, despite losses to sunstroke, still had upwards of 3’800 fighting men – some were guarding the baggage, but where were the rest? According to Alexander, they were about to have a meal.

“I myself, in command of No. 6 Company of the 93rd, was, with the headquarters of the regiment, the

remainder of the 42nd and the 79th Highlanders, in line a little beyond the brow of a hill overlooking the fort, in the direction whence we had come. About half-past twelve, we received orders to form in columns of battalions still further to the rear, pile arms, and let the men have their dinners.

Accordingly, the men’s cooking utensils were unloaded, and the native cooks proceeded to cook the men’s dinner and serve it out to them about half past one. All this time, we knew nothing of the tragedy that was being enacted in that ditch, not a quarter of a mile off. When attempts were then made by the 42nd to send their two companies their dinners, however, it began to be whispered about that they and the 4th Panjabis were losing heavily, in fact, being shot down like rabbits.”

Just as Alexander and the 93rd were settling down to their dinners, an order came up that he and his company were to escort two howitzers to the opposite side of one of the gates on the south side of the fort and batter it down. Alexander would write:

“This setting us all down to cook dinners in the middle of a serious attack on a fort, had seemed to us all, officers and men, so totally incomprehensible, that I received my orders, as pointing to some sort of action, with delight, and as the fire from the fort was too hot to trust to the bullocks, my men, when called upon to help the artillerymen to drag the two howitzers, being equally pleased to do something, started off with them at a run over very rough ground and through thick brushwood, never stopping till the artillery officer directed us to do so on the spot where he intended to bring the guns into action. The gate was protected by a high earthwork, but when the guns opened fire, it seemed to me that the shells were beautifully pitched, and they certainly knocked about the archway over the gate.

We had not, however, fired more than two or three rounds a gun, when a staff officer arrived with orders to cease firing and join headquarters. I pointed out to him what the artillery had already effected, but he reiterated his orders for me to escort the artillery back at once, which elicited the remark from one of my men, ‘ The man ‘ (meaning Walpole) doesna seem to ken his ain mind!’ The bullocks for the guns having followed us, we reluctantly obeyed orders, but as leisurely as we could, giving no hand in hauling the guns back again.”

It was General Walpole who ordered the guns to stop firing. As for the 93rd, they saw no action at all at Ruiya – the 79th and the remainder of the 4th Punjab Rifles were held in reserve in open ground behind the jungle, facing, of all things, the eastern side of the fort. Around to the rear of the fort, the cavalry with one troop of Remmington’s Horse Artillery had taken up their position on the edge of the jungle facing an open plain to intercept anyone fleeing Ruiya, once Walpole’s front and flank attack were successful, as this was the only route by which they could escape. As such, they would wait, and then wait a little longer until it became clear something was terribly wrong. Meanwhile, Brigadier Haggart of the cavalry was sending messages, repeatedly, to Walpole that the Ruiya was accessible and would be easy to capture if he moved his force from the north to the south and west flanks; Walpole blundered onwards prevented the artillery from opening a breach and“desired the officer commanding the artillery to keep up a dropping fire on the Fort from both the heavy and light guns in answer to, and to keep down that of, the enemy to which part of our infantry and several of our light guns were completely exposed.”

Colonel Brind was very aware that this whole affair at Ruiya was what he had suspected, considering the behaviour of the guides by leading them to the strongest side of the fort, base treachery. The day was passing by, and he was rapidly running out of ammunition. Brigadier Hope informed him that the 42nd were hopelessly caught in the ditch and they should either be allowed to assault by any means or retreat. Brind, on his part, decided to present Walpole with two courses of action – the artillery should be allowed to concentrate their fire at one point only, either on the north or the east, to breach the wall, preparatory for an assault; he would then use his light guns to provide cover for the storming party. The other course was that the engineers be allowed to proceed to the south side of the fort and find a position for the heavy guns to effect a breach in the curtain. Walpole agreed to the second proposal, and accordingly, Brind with Lennox and Maunsell proceeded to the south side – they had hardly reached when several things happened, seemingly all at once, that completely befuddled Walpole.

Firstly, his trusty guides disappeared, just as Brind had expected them to; then a company of the 42nd under Captain John Cheetham McLeod, ordered to advance close to the fort and examine the gate in the north wall were suddenly recalled, and the only man who appeared to still have any desire to knock sense into Walpole’s head was shot dead. This man was Adrian Hope. In this “state of perplexity and confusion,” Walpole utterly forgot he had sent Brind and the engineers to the south wall, and without sending any orders to either the artillery or the engineer officers, he ordered the infantry to retire.

Meanwhile, Brind and the engineers continued their reconnaissance of not only the south but also the west of the fort and selected a sheltered position for the heavy guns. They then decided on a spot where a breach could be made in the western wall, which was neither loopholed nor defended by bastions. Before returning with their report to Walpole, Lennox and Maunsell climbed up a small hill to make note of the best approach for the guns and the assaulting column, when to their surprise they saw the whole column moving off, away from Ruiya towards Rowdamow. Brind, convinced now that Walpole had indeed lost his mind, galloped to the head of the column to stop the retreat; he told Walpole he had found the perfect spot for a breach, and if he waited just a little longer, he could take Ruiya before nightfall. Walpole declined. The fort could wait for the next day, when another attack could be made “more thoroughly and safely”. Haggart quickly asked Brind what measures they should put in place to prevent Singh and his men from escaping during the night. Walpole did not consider this measure even moderately necessary and ordered the cavalry to return to camp.

The order to retire was greeted with just as much surprise from the troops who, having been apprised of Hope’s death, were now more eager than ever to tear Ruiya to pieces, with their bare hands if they had to, to avenge their beloved commander. Instead, as they marched away, they received a salute from Nirpat Singh’s garrison, who then proceeded to line the walls to jeer and laugh at them until they were out of sight.

Just as Haggart had surmised, during the night, Nirpat Singh and his men disappeared, swallowed up in the darkness of the vast Oudh country side – the next morning Walpole entered the empty fort and “looking down from the parapet of the wall to the spot where the men lay exposed all the previous day, and where Hope had fallen, remarked, ‘No wonder he was killed.’

The Death of Adrian Hope

Brigadier, the Honourable Adrian Hope

Brigadier, the Honourable Adrian HopeJustly concerned after the advance of the 42nd and the Punjabis Adrian Hope hastily rode up to Walpole – although no one can say for sure what he said to him as Walpole certainly did not mention it in his report, by all accounts, he held a long and apparently, strained conversation with Walpole who in his finite wisdom did not listen to a single thing Hope said.

Hope then dismounted his horse and proceeded on foot, with his ADC, Lieutenant Archibald Butter, intent on “making himself personally acquainted, at every risk, with the situation.” He advanced with Butter to the part of the counterscarp where Captain Ross-Grove was stationed to see what could possibly be done to put an end to this abominable situation. While considering whether Ruiya could be stormed or not, Hope stood up to get a better view of the position when a bullet fired by a man hidden in a tree hit him in left side of his neck, and passed downwards to his chest towards his heart. He fell backwards against Ross-Grove, who laid him on the ground. Lieutenant Butter, horrified, knelt next to Hope, shouting out for someone to bring a doctor. Holding Butter’s hand, Hope whispered, “Say a prayer for me,” closed his eyes and died. Butter would write a letter to Hope’s brother, Charles, a few days later, presenting a suitably heroic version of his death with many more last words; the version he told Munro when he brought Hope’s body to him seems, when considered in the clear light of time, the most accurate. Curiously, the press received their own version, and a suitably heroic portrait of his death was soon in circulation. It would also be captioned, “Death of Brigadier Adrian Hope in the attack on the Fort of Roodmow, April 15th 1858”, and would appear in various publications of the day.

The son of General John Hope, 4th Earl of Hopetoun, Adrian Hope served with the 60th Rifles between 1838 and 1851. He fought in the Kaffir War and at Crimea, notably at the battles of Alma and Inkerman. He exchanged to the 93rd Highlanders, who would be one of the first regiments to arrive in India at the outbreak of the mutiny. Hope fought under Sir Colin Campbell at the relief of Lucknow and at the subsequent retaking of the city. During the mutiny, he was promoted to Colonel and received the cross of Companion of the Order of the Bath (CB). He was also universally liked, not only by the men of his regiment who revered him, but by everyone fortunate to meet him.

“Of all the leaders of men whom I have served under, he was the calmest and coolest under fire, and the most gentle and courteous in his manner to all with whom he was associated. He never uttered harsh or unkind words, but was generous in thought, speech, and act. He seldom found fault, yet, when he did so, his reproof was conveyed in the fewest words, and with the most refined consideration for the feelings of the offender; so that all, from the highest to the humblest, who served under his orders felt that he was a leader in whom they could trust, and a friend to whom they could willingly and unreservedly give respect and love. No position of danger ever seemed to move him in the least; no one ever saw him hurried, or knew from his demeanour if he was anxious under difficulties or not. He spoke to those around him in the hottest fire of battle in his usual gentle, courteous manner. Nothing escaped his notice; what had to be done by himself or at his order was done without hurry, at the right time and in the right way. One great peculiarity of his was that he often seemed to be asking advice while giving it.” (Surgeon Munro)

Being a large man with red hair, Hope was instantly recognisable; while he might not have had the same nearly magnetic power as a Nicholson, everyone agreed, “A gentler, braver spirit never breathed – a true soldier, a kind, courteous, noble gentleman in word and deed, devoted to his profession, beloved by his men, adored by his friends.” (Russell) Sir Colin Campbell trusted Hope, and the command of the division, many believed, should have been his. However, Hope was only 37 and a colonel, and Walpole, a general, outranked him. Hope should have gone on to greater things, a leader of men, a shining example of everything manly and good – it was just unfortunate that he would be the first star to fall out of Sir Colin Campbell’s tainted sky.

The funeral of Hope, Lieutenants Bramley and Douglas of the 42nd, and Lieutenant Willoughby of the 4th Punjab Rifles took place in the early evening of 16 April. They were laid to rest together with seven men of the 42nd in a double row of graves dug in a grove of mango trees.

Hope’s grave stone at Ruiya

Hope’s grave stone at RuiyaI have seen and assisted at many military funerals, but I never saw one more impressive than this. Brigadier Hope was accorded the funeral of a General Officer, the whole division being present on foot – Engineers, artillery, cavalry and infantry—and even the sick and wounded who could walk stole away from the field hospitals to be present.

The massed bands of the three Highland regiments played the Dead March, being relieved by the whole of the pipers of the three regiments, playing ‘Lochaber no more, ‘ and ‘The Flowers of the Forest .’ Viewed from my grove of trees, whence the camp could be seen half a mile off, the procession was very imposing, and the wail of the bagpipes, alternating with the solemn strains of the Dead March, was most impressive.

Each Highland regiment having its own Presbyterian Chaplain, the Rev. Mr Ross, Presbyterian Chaplain of the 42nd Highlanders, read the 90th Psalm, and the Rev. Mr Cowie, Episcopalian Chaplain to the division, the Church of England Service. There was hardly a dry eye in that large assemblage.“

For Surgeon Munro, it was not only the saddest, but the most touching military funeral he had ever witnessed – “for the lives of the brave men had been so full of promise and their deaths humanly speaking, so unnecessary.”

Back in Scotland, a memorial would be erected the following year that stands on a ridge between Linlithgow and Bo’ness, called the Hope Monument, and bears the following inscription:

“To the glory of God and in memory of Brigadier the Hon’ble. Adrian Hope C.B. Lieutenant Colonel 93rd Highlanders, youngest son of General John, Fourth Earl of Hopetoun. Born March 3rd 1821 killed before the Fort of Rohya in Oude April 15th 1858.”

Airngath Hill, Hope Monument – licenced image, © Crown Copyright: HES (Records of the Scottish National Buildings Record, Edinburgh, Scotland)

Airngath Hill, Hope Monument – licenced image, © Crown Copyright: HES (Records of the Scottish National Buildings Record, Edinburgh, Scotland)In the west aisle of the north transept of Westminster Abbey, there is also a memorial stone to Brigadier the Honourable Adrian Hope.

Returns for RuiyaStaff

Lieutenant-Colonel Adrian Hope, 93rd Royal Highlanders – killed in action.

4th Punjab Rifles

1 officer killed, two wounded, forty-six men killed and wounded (out of 105 men and six officers)

Captain William Martin Cafe – severely wounded

Lieutenant F. V. H. Sperling – slightly wounded

Lieutenant Edward C. O. Willoughby – killed in action (attached, 10th BNI)

The 42nd, India, 1860

The 42nd, India, 1860

42nd Royal Highlanders

Two officers, seven men killed, one officer and thirty-seven men wounded

Lieutenants

Bramley, Alfred Jennings – killed in action. Aged 22. Son of Reverend Thomas Jennings Bramley of Tunbridge Wells, Kent.

Cockburn, C. W. – severely wounded

Douglas, Charles – dangerously wounded. Died of wounds, 16 April.

Colour Sergeants

Ridley, Thomas – dangerously wounded. Died of wounds

Stephens, John – slightly wounded

Sergeant James Fraser – killed in action

Corporals

Hartley, Joseph – severely wounded

Ritchie, Archibald – killed in action

Thompson, Thomas – killed in action

Drummer Andrew Morris – severely wounded

Privates

Bates, Joseph – dangerously wounded. Died of wounds

Brodie, Adam – killed in action

Corbet, Samuel – slightly wounded

Crosson Robert – severely wounded

Dixon, Alfred – severely wounded in the arm

Duncan, William – mortally wounded. Died 16 April

Dunn, James – dangerously wounded. Died the same day

Eadie, James – killed in action

Forrester, William – slightly wounded

Fraser, Charles – killed in action

Gilderthorpe, Charles – dangerously wounded

Grimwood, David – severely wounded in the right groin

Hennessey, Dennis – dangerously wounded

McIntosh, William – severely wounded

McKay, Andrew – killed in action

Mackie, Alexander – dangerously wounded. Died of wounds

Sibbalds, Robert – slightly wounded

Spence, Edward – dangerously wounded, died of wounds

Wagstaff, Charles – killed in action

Wright, Robert – dangerously wounded. Died of wounds 5 May

79th Royal Highlanders

The Cameron Highlanders had two men wounded, one of whom died of his wounds

1 private mortally wounded by round shot.

93rd Royal Highlanders

Sergeant David Sim – severely wounded

Privates

Davidson, Robert – severely wounded

Harris, Alexander – slightly wounded

Lennant, James – slightly wounded

McKay, Hugh – slightly wounded

Bengal Artillery

2 horses killed; 1 European officer, 3 non-commissioned officers, 3 drummers, rank and file, wounded; 1 native rank and file, 2 horses, 5 bullocks, wounded.

1st Lieutenant H. E. Harington (VC) – severely wounded

Sergeant John Knox – severely wounded

2nd Punjab Cavalry

1 Native Rank & File wounded

Bengal Sappers and Miners

2 native NCOs wounded, 1 rank & file, wounded

Punjab Pioneers

1 European NCO wounded

Total—2 European officers, 1 non-commissioned officer, 6 drummers, rank and file; 1 native officer, 1 non-commissioned officer, 7 drummers, rank and file, killed; 6 European officers, 8 non-commissioned officers, 36 drummers, rank and file, 5 native non-commissioned officers, 34 drummers, rank and file, wounded.

Grand Total—18 European and native officers and men, and 2 horses, killed; 89 European and native officers and men, 2 horses, and 5 bullocks, wounded.

Walpole was quick to mention everyone he possibly could in his despatch.

“I have received the most willing support from all under my command during this operation; and I beg particularly to offer my best thanks to Brigadier Haggart, commanding the cavalry, and to Major Brind, commanding the artillery, for their most able and valuable assistance; also to Captain Lennox, the senior engineer officer, to Lieutenant- Colonel Hay, commanding the 93rd Regiment, who succeeded to the command of the infantry brigade on the death of Brigadier Hope, to Lieutenant- Colonel Cameron, commanding 42nd Regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel Taylor, commanding 79th Regiment; to Captain Cafe, commanding 4th Punjaub Infantry, who, I regret to say, was severely wounded; to Lieutenant-Colonel Tombs, and Major Remmington, commanding troops of horse artillery; to Captain Francis, commanding heavy guns; to Captain Coles, commanding 9th Lancers, and Captain Browne, commanding 2nd Punjaub Cavalry.

I beg also to return my best thanks to the officers of my staff, Captain Barwell, Deputy Assistant Adjutant-General; Captain Carey, Deputy Assistant Quartermaster-General; Captain Warner, aide-de-camp, and Lieutenant Eccles, Rifle Brigade, my extra aide-de-camp.

Enclosed, I beg to forward a list of the casualties, and likewise a sketch of the fort, which has been made in a hurry, but will afford information of the nature of the work.

I have, &c.,

R. WALPOLE, Brigadier-General, Commanding Field Force.

The fort at Ruiya was destroyed. With it should have gone Walpole’s reputation.

Sources:

Behan, T. L. – Bulletins & Other State Intelligence for the Year 1858 – Part III (London Gazette Office, Harrison & Sons, 1860)

Burgoyne, Roderick Hamilton – Historical Records of the 93rd Sutherland Highlanders (London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1883)

Bush, June – The Warner Letters (New Delhi: Rupa & Co., 2008)

Gordon-Alexander, Lieut. Col. W. – Recollections of a Highland Subaltern (London: Edward Arnold, 1898)

Groves, Lt.-Col. Percy – History of the 42nd Royal Highlanders – “The Black Watch” (Edinburgh & London, W. & A.K. Johnston, 1893)

Mackenzie, Capt. T.A., Lt. &Adjt. Ewart, J. S., Lt. Findlay, C. – Historical Records of the 79th Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders (London: Hamilton, Adams & Co., Devonport: A.H. Swiss, 1887)

Malleson, Col. G.B. – History of the Indian Mutiny, Vol. II (London: William H. Allen & Co., 1879)

Munro, Surgeon-General – Reminiscences of Military Service with the 93rd Highlanders ( London: Hurst & Blackett Publishers, 1883)

Munro, Surgeon General – Records of Service and Campaigning in Many Lands, Vol II (London: Hurst & Blackett Ltd., 1887)

Russell, William Howard– My Diary in India, Vol. I (London: Routledge, Warne & Routledge, 1860)