Eva Chatterji's Blog

January 10, 2026

VCs of 1857-1859: A-D

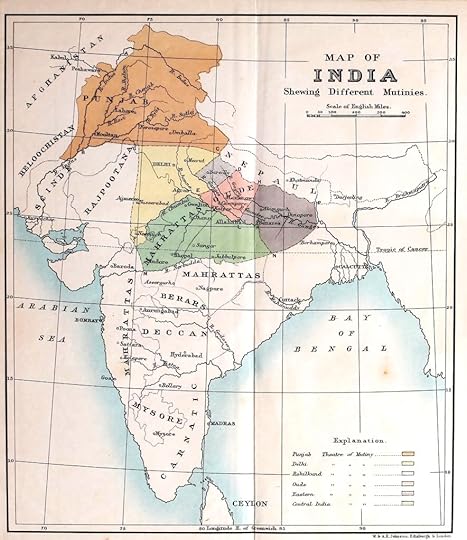

In order to save the reader time, I have compiled a list of where one can find the specific post that looks in detail at the Victoria Cross recipient. The list is organised alphabetically, and all 182 names have been listed. Where there is no link, the campaign or action has not yet been covered and will be added in due time.

For some background on the Victoria Cross itself, the reader may avail themselves of

How To Win a Victoria Cross

And for an explanation of the Lucknow VCs, there is

Some Thoughts on the Lucknow VCs

I wish you many hours of delightful exploration into the recipients of the Victoria Cross for the Indian Mutiny.

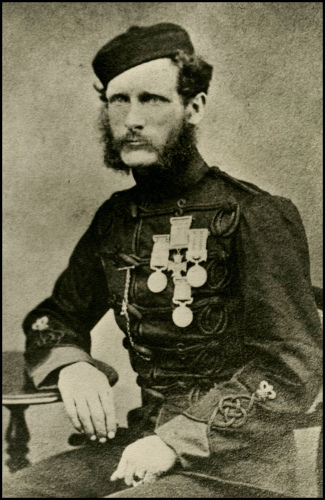

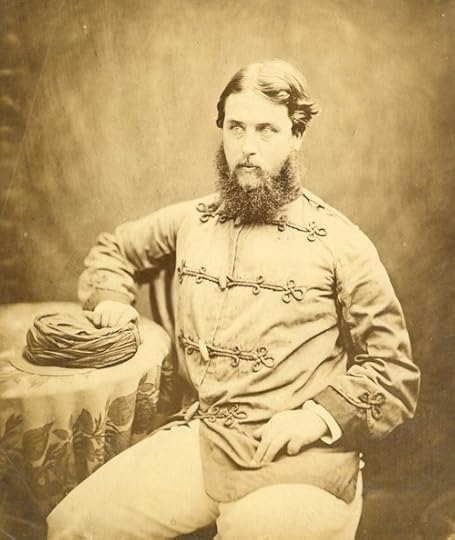

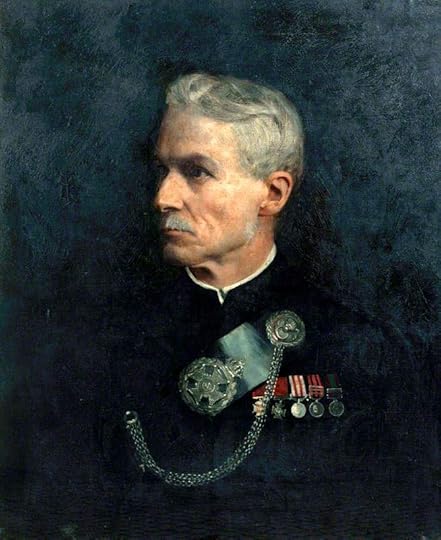

Augustus Anson

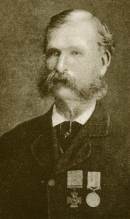

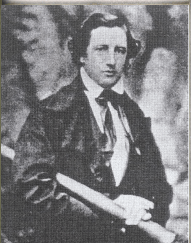

Augustus Anson Charles Anderson

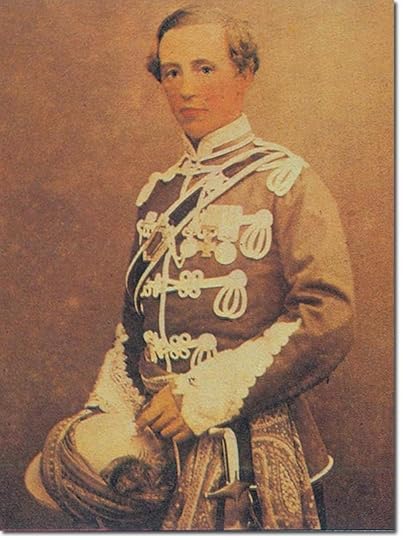

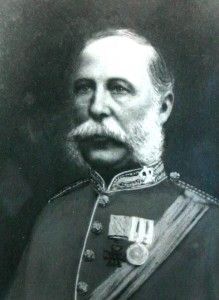

Charles Anderson Robert Aikman

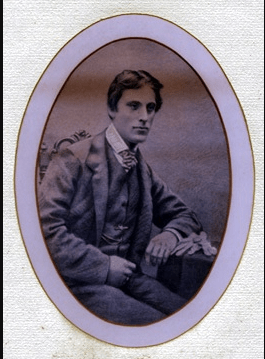

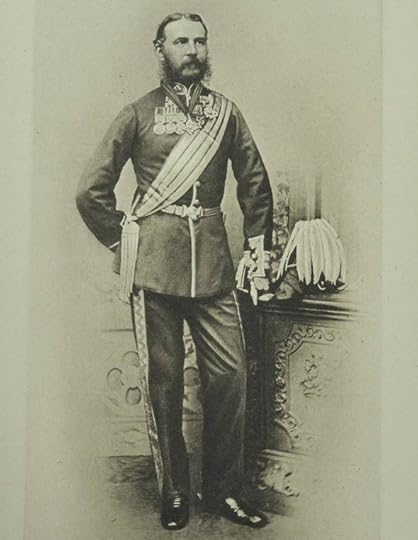

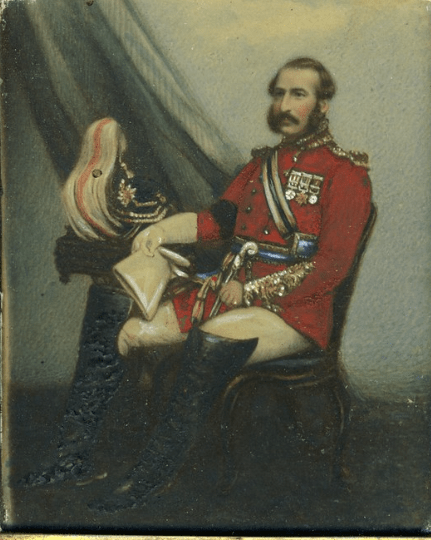

Robert Aikman Desanges, Louis William; Lieutenant Frederick Robertson Aikman (1828-1888), 4th Regiment (Bengal) Native Infantry, Commanding 3rd Regiment (Sikh) Irregular Cavalry, Winning the Victoria Cross NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkAddison, Henry (Pte) 43rd FootKurrereah2 January 1859 Aikman, Frederick (Lt) 4th BNI Jalandhar CavalryAmethi1 March 1858Frederick Robertson-Aikman VC The Robertson-Aikmans of the RossAitken, Robert (Lt) 13th BNILucknow30 June 1857 to 22 November 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to GloryAnderson, Charles (Pte) 2nd Dragoon GuardsSudeela, Oudh8 October 1858 Anson, Augustus (Capt) 9th LancersBulandshahr; Lucknow28 Sept. 1857, 16 Nov. 1857The Seven VCs of Bulandshahr Courage in ChaosB.

Desanges, Louis William; Lieutenant Frederick Robertson Aikman (1828-1888), 4th Regiment (Bengal) Native Infantry, Commanding 3rd Regiment (Sikh) Irregular Cavalry, Winning the Victoria Cross NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkAddison, Henry (Pte) 43rd FootKurrereah2 January 1859 Aikman, Frederick (Lt) 4th BNI Jalandhar CavalryAmethi1 March 1858Frederick Robertson-Aikman VC The Robertson-Aikmans of the RossAitken, Robert (Lt) 13th BNILucknow30 June 1857 to 22 November 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to GloryAnderson, Charles (Pte) 2nd Dragoon GuardsSudeela, Oudh8 October 1858 Anson, Augustus (Capt) 9th LancersBulandshahr; Lucknow28 Sept. 1857, 16 Nov. 1857The Seven VCs of Bulandshahr Courage in ChaosB.Some Points of Interest: Captain James Blair and Lieutenant Robert Blair were cousins, and they won their VCs within a month of each other. Many of their relatives were killed during the mutiny, most of them at the Cawnpore massacre.

Captain Samuel Browne, who lost an arm during the mutiny, would be the inventor of the Sam Browne Belt that hooked into his waist belt before running diagonally over his right shoulder to steady his scabbard. For practical reasons, the waist belt securely carried his pistol in a flap-holster on his right hip and a neck strap for his binocular case. The belt would eventually become a uniform standard. The Indian Army would continue to be worn by officers and junior COs until the 1980s, and remains part of the uniform for officers in the Indian police force.

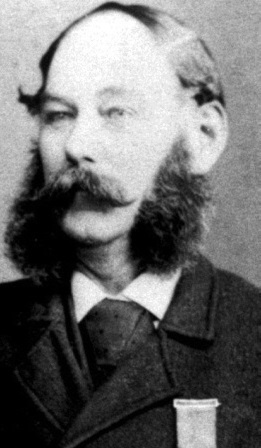

William Bradshaw

William Bradshaw Robert Blair

Robert Blair William Bankes

William Bankes Desanges, Louis William; Lieutenant Thomas Adair Butler (1836-1901), 1st (Bengal) European Fusiliers, Winning the Victoria Cross NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkBaker, Charles George (Lt) Bengal Military Police BattalionSahejani Bhojpur27 September 1858 Bambrick, Valentine (Pte) 60th RiflesBareilly6 May 1858 Bankes, William (Lt) 7th HussarsLucknow19 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IVBlair, James (Capt) 2nd Bombay Light CavalryNeemuch; Jeerum12 Aug. 1857, 23 Oct. 1857Most Effectual Charges—James Blair, VCBlair, Robert (Lt) 2nd Dragoon GuardsBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrBogle, Andrew (Lt) 78th HighlandersOonao29 July 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIBoulger, Abraham (L/Cpl) 84th FootLucknow12 July 1857 to 25 Sept. 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIBradshaw, William (Asst. Surg.) 90th FootLucknow26 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIBrennan, Joseph (Bdr) Royal ArtilleryJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsBrown, Francis (Lt) 1st Bengal European FusiliersNarnaul16 November 1857Francis David Millet Brown The Browns of IndiaBrowne, Samuel (Capt) 46th BNI, 2nd Punjab Irreg. CavalrySeerporah31 August 1858 Buckley, John (DAC) Comm. Dept.Delhi11 May 1857God Shall Wipe All Tears from their Eyes Butler, Thomas (Lt) 1st Bengal European FusiliersLucknow9 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IByrne, James, (Pte) 86th FootJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsC.

Desanges, Louis William; Lieutenant Thomas Adair Butler (1836-1901), 1st (Bengal) European Fusiliers, Winning the Victoria Cross NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkBaker, Charles George (Lt) Bengal Military Police BattalionSahejani Bhojpur27 September 1858 Bambrick, Valentine (Pte) 60th RiflesBareilly6 May 1858 Bankes, William (Lt) 7th HussarsLucknow19 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IVBlair, James (Capt) 2nd Bombay Light CavalryNeemuch; Jeerum12 Aug. 1857, 23 Oct. 1857Most Effectual Charges—James Blair, VCBlair, Robert (Lt) 2nd Dragoon GuardsBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrBogle, Andrew (Lt) 78th HighlandersOonao29 July 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIBoulger, Abraham (L/Cpl) 84th FootLucknow12 July 1857 to 25 Sept. 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIBradshaw, William (Asst. Surg.) 90th FootLucknow26 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIBrennan, Joseph (Bdr) Royal ArtilleryJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsBrown, Francis (Lt) 1st Bengal European FusiliersNarnaul16 November 1857Francis David Millet Brown The Browns of IndiaBrowne, Samuel (Capt) 46th BNI, 2nd Punjab Irreg. CavalrySeerporah31 August 1858 Buckley, John (DAC) Comm. Dept.Delhi11 May 1857God Shall Wipe All Tears from their Eyes Butler, Thomas (Lt) 1st Bengal European FusiliersLucknow9 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IByrne, James, (Pte) 86th FootJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsC.Some Points of Interest: Lieutenant Thomas Cadell was the cousin of another VC winner, Samuel Hill Lawrence.

Lieutenant William Cubitt was the brother-in-law of Lieutenant James Hills (VC) and the uncle of another VC recipient, Brigadier-General Lewis Pugh Evans, who gained his at Zonnebeke, Belgium in October 1917.

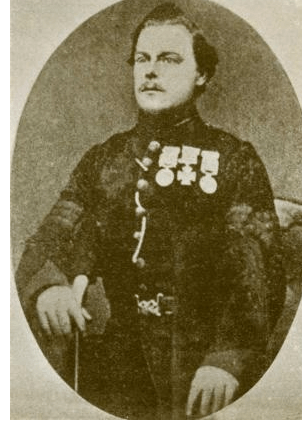

Hugh Cochrane

Hugh Cochrane William Cubitt

William Cubitt Herbert Clougstoun

Herbert Clougstoun Thomas Cadell

Thomas Cadell Cornelius Coughlan

Cornelius Coughlan Volunteer George Chicken Winning the Victoria CrossNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkCadell, Thomas (Lt) 2nd Bengal European FusiliersDelhi12 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsCafe, William (Capt) 56th BNI, 2nd Punjab InfantryFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadCameron, Aylmer (Lt) 72nd HighlandersKotah30 March 1858A Legacy in WarCarlin, Patrick (Pte) 13th FootAzimgarh6 April 1858 Champion, James (TSM) 8th HussarsBeejapore8 September 1858 Chicken, George (Volunt.) Naval Brigade, Bengal Military Police BattalionSuhejnee27 September 1858 Clogstoun, Herbert (Capt) 19th Madras NIChichumbah15 January 1859 Cochrane, Hugh (Lt) 86th FootBetwa1 April 1858Taking the Gun – Hugh Stewart Cochrane VCConnolly, William (Gnr) Bengal Horse ArtiileryJhelum7 July 1857No Sir, I’ll Not GoCook, Walter (Pte) 42nd HighlandersMaylah Ghat15 January 1859 Coughlan, Cornelius (C/Sgt)Badli-ki-Serai8 June 1857The VCs of Badli-ki-SeraiCrowe, Joseph (Lt) 78th HighlandersBoursekee Chowkee12 August 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIICubitt, William (Lt) 13th BNIChinhut30 June 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory D.

Volunteer George Chicken Winning the Victoria CrossNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkCadell, Thomas (Lt) 2nd Bengal European FusiliersDelhi12 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsCafe, William (Capt) 56th BNI, 2nd Punjab InfantryFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadCameron, Aylmer (Lt) 72nd HighlandersKotah30 March 1858A Legacy in WarCarlin, Patrick (Pte) 13th FootAzimgarh6 April 1858 Champion, James (TSM) 8th HussarsBeejapore8 September 1858 Chicken, George (Volunt.) Naval Brigade, Bengal Military Police BattalionSuhejnee27 September 1858 Clogstoun, Herbert (Capt) 19th Madras NIChichumbah15 January 1859 Cochrane, Hugh (Lt) 86th FootBetwa1 April 1858Taking the Gun – Hugh Stewart Cochrane VCConnolly, William (Gnr) Bengal Horse ArtiileryJhelum7 July 1857No Sir, I’ll Not GoCook, Walter (Pte) 42nd HighlandersMaylah Ghat15 January 1859 Coughlan, Cornelius (C/Sgt)Badli-ki-Serai8 June 1857The VCs of Badli-ki-SeraiCrowe, Joseph (Lt) 78th HighlandersBoursekee Chowkee12 August 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIICubitt, William (Lt) 13th BNIChinhut30 June 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory D.  John Daunt

John Daunt John Divane

John Divane Bernard Diamond

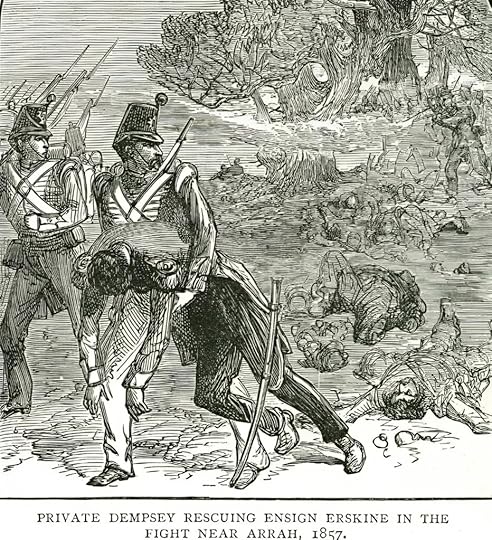

Bernard Diamond NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkDaunt, John (Lt) 11th BNIChatra2 October 1857The Chatra VCsDavis, James (Pte) 42nd HighlandersFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadDempsey, Denis (Pte) 10th FootArrah; Lucknow12 August 1857, 14 March 1858Quo Fata Vocant

NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkDaunt, John (Lt) 11th BNIChatra2 October 1857The Chatra VCsDavis, James (Pte) 42nd HighlandersFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadDempsey, Denis (Pte) 10th FootArrah; Lucknow12 August 1857, 14 March 1858Quo Fata Vocant The Valorous Twelve – Part IIIDiamond, Bernard (Sgt) Bengal Horse ArtilleryBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrDivane, John (Pte) 60th RiflesDelhi10 September 1857Acts of BraveryDonohoe, Patrick (Pte) 9th LancersBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrDowling, William (Pte) 32nd Foot Lucknow4 July 1857, 27 Sept. 1857 The Path of Duty is the Way to GloryDuffy, Thomas (Pte) 1st Madras European FusiliersLucknow26 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVDunlay, John (L/Cpl) 93rd HighlandersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in ChaosDynon, Denis (Sgt) 53rd FootChatra2 October 1857The Chatra VCs

Abbreviations:

ADC – Aide de CampAsst. Surg. – Assistant SurgeonBdr – BombardierBglr – BuglerC/Sergt – Colour SergeantCapt – CaptainCpl – CorporalD – DrummerDAC – Deputy Assistant CommissaryDAQMG – Deputy Assistant Quarter Master GeneralEns – EnsignGnr – GunnerL/Cpl – Lance CorporalLt – LieutenantLt Adjt – Lieutenant AdjutantMaj – MajorPte – PrivateSgt – SergeantSgt Maj – Sergeant MajorQMS- Quartermaster SergeantSurg – SurgeonTptr – TrumpeterTSM – Troop Sergeant MajorVolunt. – VolunteerVCs of 1857-1859: F-I

Thomas Flynn

Thomas Flynn Alfred Ffrench

Alfred Ffrench The Defence of Delhi Magazine, May 1857NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkFarquharson, Francis (Lt) 42nd HighlandersLucknow9 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IFfrench, Alfred (Lt) 53rd FootLucknow16 November 1857Courage in ChaosFitzgerald, Richard (Gnr) Bengal Horse ArtilleryBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrFlynn, Thomas (D) 64th FootCawnpore28 November 1857Thomas Flynn of H.M.’s 64thForrest George (Lt) Bengal Veterans EstablishmentDelhi11 May 1857God Shall Wipe All Tears from their Eyes IFraser, Charles (Maj) 7th HussarsRiver Raptee31 December 1858 Freeman, John (Pte) 9th LancersAgra10 October 1857Four Extraordinary MenG.

The Defence of Delhi Magazine, May 1857NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkFarquharson, Francis (Lt) 42nd HighlandersLucknow9 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IFfrench, Alfred (Lt) 53rd FootLucknow16 November 1857Courage in ChaosFitzgerald, Richard (Gnr) Bengal Horse ArtilleryBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrFlynn, Thomas (D) 64th FootCawnpore28 November 1857Thomas Flynn of H.M.’s 64thForrest George (Lt) Bengal Veterans EstablishmentDelhi11 May 1857God Shall Wipe All Tears from their Eyes IFraser, Charles (Maj) 7th HussarsRiver Raptee31 December 1858 Freeman, John (Pte) 9th LancersAgra10 October 1857Four Extraordinary MenG.Some Points of Interest:

Major John Guise was already missing an arm when he fought in the Indian Mutiny

Major Charles Gough and Lieutenant Hugh Gough were brothers, and one of Charles’ exploits was saving Hugh’s life. Charles’ son, John, would receive a VC for actions in Somaliland in 1903.

George Chicken was one of the five civilians to be awarded a VC.

John Guise

John Guise Charles Goodfellow

Charles Goodfellow William Goat

William Goat Stephen Garvin

Stephen Garvin Hugh Gough

Hugh Gough Colour Sergeant William Gardner Rescuing Lt. Col. Cameron at BareillyNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkGardner, William (C/Sgt) 42nd HighlandersBareilly5 May 1858 Garvin, Stephen (C/Sgt) 60th RiflesDelhi23 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsGill, Peter (Sgt-Maj) Loodiana RegimentBenares4 June 1857Humble Beginnings – The Three VCs of BenaresGoat, William (L/Cpl) 9th LancersLucknow6 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IVGoodfellow, Charles (Lt) Bombay EngineersKathiawar6 October 1859 Gore-Browne, Henry (Capt) 32nd FootLucknow21 August 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to GloryGough, Charles (Maj) 5th Bengal European Cavalry, Guides CorpsKhurkowdah, Sumshabad; Meanganj15 – 18 August; 27 Jan. 1858; 3 Feb. 1858Spirited DaringGough, Hugh (Lt) 1st Bengal European Light Cavalry, Hodson’s HorseAlambagh; Jelalabad Fort12 Nov. 1857, 25 Feb. 1858Four Extraordinary MenGraham, Patrick (Pte) 90th FootLucknow17 November 1857Courage in ChaosGrant, Peter (Pte) )3rd HighlandersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIGrant, Robert (Cpl) 5th FootAlambagh24 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIGreen, Patrick (Pte) 75th FootDelhi11 September 1857Acts of BraveryGuise, Guise (Maj) 90th FootLucknow17 November 1857Courage in ChaosH.

Colour Sergeant William Gardner Rescuing Lt. Col. Cameron at BareillyNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkGardner, William (C/Sgt) 42nd HighlandersBareilly5 May 1858 Garvin, Stephen (C/Sgt) 60th RiflesDelhi23 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsGill, Peter (Sgt-Maj) Loodiana RegimentBenares4 June 1857Humble Beginnings – The Three VCs of BenaresGoat, William (L/Cpl) 9th LancersLucknow6 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IVGoodfellow, Charles (Lt) Bombay EngineersKathiawar6 October 1859 Gore-Browne, Henry (Capt) 32nd FootLucknow21 August 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to GloryGough, Charles (Maj) 5th Bengal European Cavalry, Guides CorpsKhurkowdah, Sumshabad; Meanganj15 – 18 August; 27 Jan. 1858; 3 Feb. 1858Spirited DaringGough, Hugh (Lt) 1st Bengal European Light Cavalry, Hodson’s HorseAlambagh; Jelalabad Fort12 Nov. 1857, 25 Feb. 1858Four Extraordinary MenGraham, Patrick (Pte) 90th FootLucknow17 November 1857Courage in ChaosGrant, Peter (Pte) )3rd HighlandersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIGrant, Robert (Cpl) 5th FootAlambagh24 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIGreen, Patrick (Pte) 75th FootDelhi11 September 1857Acts of BraveryGuise, Guise (Maj) 90th FootLucknow17 November 1857Courage in ChaosH. Alfred Heathcoate

Alfred Heathcoate Hastings Harington

Hastings Harington Clement HeneageNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkHackett, Thomas (Lt) 23rd FootLucknow18 November 1857Courage in Chaos IVHall, William (Capt.of the Foretop) Naval BrigadeLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIIHancock, Thomas (Pte) 9th LancersDelhi, 19 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsHarington, Hastings (Lt) Bengal Horse ArtilleryLucknow14-22 November 1857Courage in ChaosHarrison, John (Leading Seaman) Naval BrigadeLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIIHartigan, Henry (Sgt) 9th LancersBadli-ki-Serai; Agra8 June 1857, 10 October 1857The VCs of Badli-ki-Serai

Clement HeneageNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkHackett, Thomas (Lt) 23rd FootLucknow18 November 1857Courage in Chaos IVHall, William (Capt.of the Foretop) Naval BrigadeLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIIHancock, Thomas (Pte) 9th LancersDelhi, 19 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsHarington, Hastings (Lt) Bengal Horse ArtilleryLucknow14-22 November 1857Courage in ChaosHarrison, John (Leading Seaman) Naval BrigadeLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIIHartigan, Henry (Sgt) 9th LancersBadli-ki-Serai; Agra8 June 1857, 10 October 1857The VCs of Badli-ki-SeraiFour Extraordinary MenHavelock-Allan, Henry (Lt) 10th Foot, ADC to Sir H. HavelockCawnpore16 July 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIHawkes, David (Pte) Rifle BrigadeLucknow11 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IIHawthorne, Robert (Bglr), 52nd FootDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraveryHeathcote, Alfred (Lt) 60th RiflesDelhiJune to September 1857Spirited DaringHeneage, Clement (Capt) 8th HussarsGwalior17 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IIHill, Samuel (Sgt) 90th FootLucknow17 November 1857Courage in ChaosHills, James (2nd Lt) Bengal Horse ArtilleryDelhi9 July 1857Spirited DaringHollis, George (Farrier) 8th HussarsGwalior17 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IIHollowell, James (Pte) 78th HighlandersLucknow26 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIHolmes, Joel (Pte) 84th FootLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVHome, Anthony (Surg) 90th FootLucknow26 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIHome, Duncan (Lt) Bengal Sappers and MinersDelhi14 September 1857The 14th of September

The funeral of William HallI.

The funeral of William HallI.  James McLeod Innes

James McLeod Innes Charles IrwinNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkInnes, James McLeod (Lt) Bengal EngineersBengal Sappers and MinersSultanpore A Gallant ManIrwin, Charles (Pte) 53rd Foot53rd Regiment of FootLucknowCourage in Chaos

Charles IrwinNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkInnes, James McLeod (Lt) Bengal EngineersBengal Sappers and MinersSultanpore A Gallant ManIrwin, Charles (Pte) 53rd Foot53rd Regiment of FootLucknowCourage in Chaos Desanges, Louis William; Surgeon (later Surgeon General) Anthony Dickson Home (1826-1914), VC, KCB, and Assistant Surgeon William Bradshaw (1830-1861), VC, 90th Regiment of Foot (Perthshire Volunteers) (Light Infantry), Lucknow, 1857

Desanges, Louis William; Surgeon (later Surgeon General) Anthony Dickson Home (1826-1914), VC, KCB, and Assistant Surgeon William Bradshaw (1830-1861), VC, 90th Regiment of Foot (Perthshire Volunteers) (Light Infantry), Lucknow, 1857Abbreviations

ADC – Aide de CampAsst. Surg. – Assistant SurgeonBdr – BombardierBglr – BuglerC/Sergt – Colour SergeantCapt – CaptainCpl – CorporalD – DrummerDAC – Deputy Assistant CommissaryDAQMG – Deputy Assistant Quarter Master GeneralEns – EnsignGnr – GunnerL/Cpl – Lance CorporalLt – LieutenantLt Adjt – Lieutenant AdjutantMaj – MajorPte – PrivateQMS – Quartermaster SergeantSgt – SergeantSgt Maj – Sergeant MajorSurg – SurgeonTptr – TrumpeterTSM – Troop Sergeant MajorVolunt. – VolunteerVCs of 1857-1859: J-M

Alfred Jones

Alfred Jones Joseph Jee

Joseph Jee Henry Jerome

Henry Jerome Surgeon Jee at Lucknow J.NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkJarrett, Hanson (Lt) 26th BNIBaroun14 October 1858 Jee, Joseph (Surg) 78th HighlandersLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVJennings, Edward (Rough Rider) Bengal Horse ArtilleryLucknow14-22 November 1857Courage in ChaosJerome, Henry (Capt) 86th FootJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsJones, Alfred (Lt) 9th LancersBadli-ki-Serai8 June 1857The VCs of Badli-ki-SeraiK.

Surgeon Jee at Lucknow J.NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkJarrett, Hanson (Lt) 26th BNIBaroun14 October 1858 Jee, Joseph (Surg) 78th HighlandersLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVJennings, Edward (Rough Rider) Bengal Horse ArtilleryLucknow14-22 November 1857Courage in ChaosJerome, Henry (Capt) 86th FootJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsJones, Alfred (Lt) 9th LancersBadli-ki-Serai8 June 1857The VCs of Badli-ki-SeraiK.  Richard Keatinge

Richard Keatinge Robert Kells

Robert Kells William Kerr

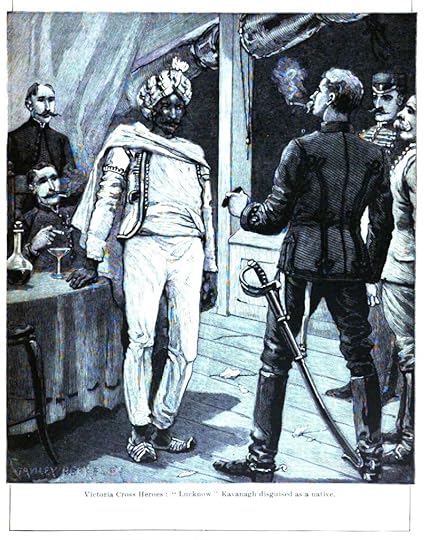

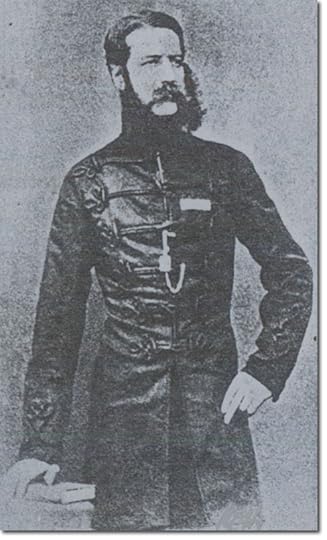

William Kerr NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkKavanagh, Thomas Bengal Civil ServiceLucknow9 November 1857A Civilian in the MutinyKeatinge, Richard (Maj) Bombay ArtilleryChanderi17 March 1858Richard Harte Keating, VCKells, Robert (L/Cpl) 9th LancersBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrKenny, James (Pte)Lucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIKerr, William (Lt) 24th Bombay NIKolapore10 July 1857Dashing BraveryKirk, John (Pte) 10th FootBenares4 June 1857Humble Beginnings – The Three VCs of BenaresL.

NamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkKavanagh, Thomas Bengal Civil ServiceLucknow9 November 1857A Civilian in the MutinyKeatinge, Richard (Maj) Bombay ArtilleryChanderi17 March 1858Richard Harte Keating, VCKells, Robert (L/Cpl) 9th LancersBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrKenny, James (Pte)Lucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIKerr, William (Lt) 24th Bombay NIKolapore10 July 1857Dashing BraveryKirk, John (Pte) 10th FootBenares4 June 1857Humble Beginnings – The Three VCs of BenaresL. James Leith

James Leith Samuel Hill Lawrence

Samuel Hill Lawrence Harry Lyster

Harry Lyster Lieutenant Leith Winning the Victoria CrossNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkLambert, George (Sgt Maj) 84th FootOonao, Bithur; Lucknow29 June 1857, 16 August, 25 SeptemberThe Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIILaughnan, Thomas (Gnr) Bengal Horse ArtilleryLucknow14-22 November 1857Courage in ChaosLawrence, Samuel (Lt) 32nd FootLucknow7 July 1857, 26 SeptemberThe Path of Duty is the Way to GloryLeith, James (Lt) 14th Light DragoonsBetwa1 April 1858He Knows Little Care – James Leith VCLyster, Harry (Lt) 72nd BNIKalpi23 May 1858 M.

Lieutenant Leith Winning the Victoria CrossNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkLambert, George (Sgt Maj) 84th FootOonao, Bithur; Lucknow29 June 1857, 16 August, 25 SeptemberThe Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIILaughnan, Thomas (Gnr) Bengal Horse ArtilleryLucknow14-22 November 1857Courage in ChaosLawrence, Samuel (Lt) 32nd FootLucknow7 July 1857, 26 SeptemberThe Path of Duty is the Way to GloryLeith, James (Lt) 14th Light DragoonsBetwa1 April 1858He Knows Little Care – James Leith VCLyster, Harry (Lt) 72nd BNIKalpi23 May 1858 M. Herbert Macphersson

Herbert Macphersson Ross Mangles

Ross Mangles Valentine McMaster

Valentine McMaster George Monger

George Monger Arthur Mayo

Arthur Mayo Patrick McHale

Patrick McHale James MillerNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkMacKay, David (Pte) 93rd HighlandersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIMacpherson, Herbert (Lt) 78th HighlandersLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVMahoney, Patrick (Sgt) 1st Madras European FusiliersMangalwar21 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIMangles, Ross (Civilian) Bengal Civil ServiceArrah30 July 1857Quo Fata VocantMaude, Francis (Capt) Royal ArtilleryLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVMayo, Arthur (Midshipman) Naval BrigadeDacca22 November 1857Midshipman Arthur Mayo, VC

James MillerNamePlace of ActionDate of ActionLinkMacKay, David (Pte) 93rd HighlandersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIMacpherson, Herbert (Lt) 78th HighlandersLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVMahoney, Patrick (Sgt) 1st Madras European FusiliersMangalwar21 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIMangles, Ross (Civilian) Bengal Civil ServiceArrah30 July 1857Quo Fata VocantMaude, Francis (Capt) Royal ArtilleryLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVMayo, Arthur (Midshipman) Naval BrigadeDacca22 November 1857Midshipman Arthur Mayo, VCThe Abor Expedition of 1859McBean, William (Lt) 93rd HighlandersLucknow11 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IIMcDonell, William (Civilian) Bengal Civil ServiceArrah30 July 1857Quo Fata VocantMcGovern, John (Pte) 1st Bengal European FusiliersDelhi23 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCs

The Legion LostMcGuire, James (Sgt) 1st Bengal European FusiliersDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraveryMcHale, Patrick (Pte) 5th FootLucknow2 October 1857, 22 December 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVMcInnes, Hugh (Gnr) Bengal ArtilleryLucknow14-22 November 1857Courage in ChaosMcManus, Peter (Pte) 5th FootLucknow26 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIMcMaster, Valentine (Asst.Surg.) 78th HighlandersLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVMcPherson, Stewart (C/Sgt) 78th HighlandersLucknow26 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVMcQuirt, Bernard (Pte) 95th FootRowa6 January 1858Rajputana, 1858Millar, Duncan (Pte) 42nd HighlandersMaylah Ghat15 January 1859 Miller, James (Conductor) Bengal Ordnance DepotFatehpur Sikri (Agra)28 October 1857Saving Lieutenant GlubbMonaghan, Thomas (Tptr) 2nd Dragoon GuardsJamo8 October 1858 Monger, George (Pte) 23rd FootLucknow18 November 1857Courage in Chaos IVMorley, Samuel (Pte) Military TrainAzimgarh15 April 1858 Munro, James (C/Sgt) 93rd FootLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIMurphy, Michael (Pte) Military TrainAzimgarh15 April 1858 Mylott, Patrick (Pte) 84th FootLucknow12 July 1857 to 25 SeptemberThe Path of Duty is the Way to Glory III

Francis Maude, sighting his gun, Lucknow 1858

Francis Maude, sighting his gun, Lucknow 1858Abbreviations:

ADC – Aide de CampAsst. Surg. – Assistant SurgeonBdr – BombardierBglr – BuglerC/Sergt – Colour SergeantCapt – CaptainCpl – CorporalD – DrummerDAC – Deputy Assistant CommissaryDAQMG – Deputy Assistant Quarter Master GeneralEns – EnsignGnr – GunnerL/Cpl – Lance CorporalLS – Leading SeamanLt – LieutenantLt Adjt – Lieutenant Adjutant2nd Lt – Second LieutenantMaj – MajorPte – PrivateQMS – Quartermaster SergeantSgt – SergeantSgt Maj – Sergeant MajorSurg – SurgeonTptr – TrumpeterTSM – Troop Sergeant MajorVolunt. – Volunteer

VCs of 1857-1859: N-R

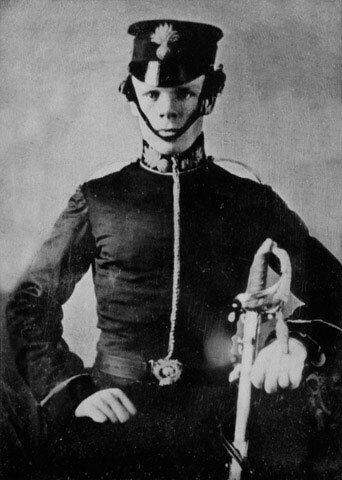

William NapierN.NamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkNapier, William (Sgt)13th FootAzimgarh6 April 1858 Nash, William (Cpl) Rifle BrigadeLucknow11 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IINewell, Robert (Pte) 9th LancersLucknow19 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IVO.

William NapierN.NamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkNapier, William (Sgt)13th FootAzimgarh6 April 1858 Nash, William (Cpl) Rifle BrigadeLucknow11 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IINewell, Robert (Pte) 9th LancersLucknow19 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IVO. William Olpherts

William Olpherts William OxenhamNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkOlpherts, William (Capt) Bengal ArtilleryLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVOxenham, William (Pte) 32nd FootLucknow30 June 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to GloryP.

William OxenhamNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkOlpherts, William (Capt) Bengal ArtilleryLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVOxenham, William (Pte) 32nd FootLucknow30 June 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to GloryP. Harry Prendergast

Harry Prendergast Everard Philips

Everard Philips

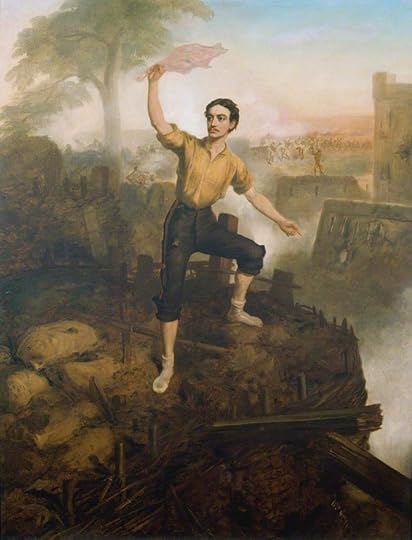

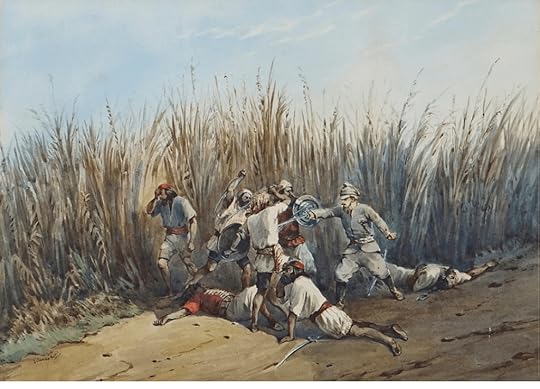

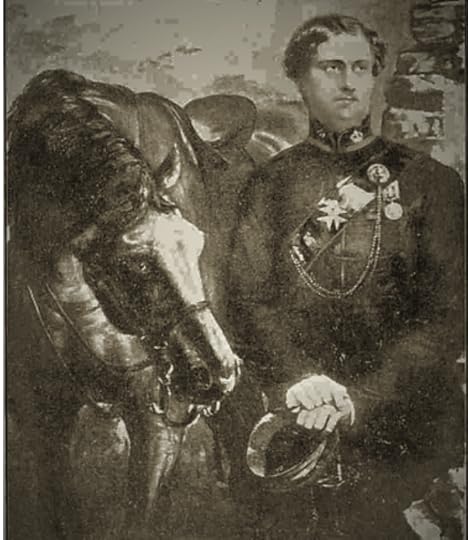

Desanges, Louis William; Captain (later General Sir) Dighton MacNaghten Probyn, 2nd Punjab Cavalry, at the Battle of Agra NamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkPark, James (Gnr) Bengal ArtilleryLucknow14-22 November 1857Courage in ChaosPaton, John (Sgt) 93rd HighlandersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIIPearson, James (Pte) 86th FootJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsPearson, John (Pte) 8th HussarsGwalior17 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IIPhillipps, Everard (Ens) 11 BNIDelhi30 May 1857 to 18 September 1857Returns for Delhi 15th – 22nd of SeptemberPrendergast, Harry (Lt) Madras EngineersMandsaur21 November 1857The Path Before Him Always BrightProbyn, Dighton (Capt) 2nd Punjab CavalryAgra1857 to 1858For Distinguished Gallantry, Captain Dighton Probyn, VCPurcell, John (Pte) 9th LancersDelhi19 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsPye, Charles (Sgt Maj) 53rd FootLucknow17 November 1857Courage in Chaos IVR.

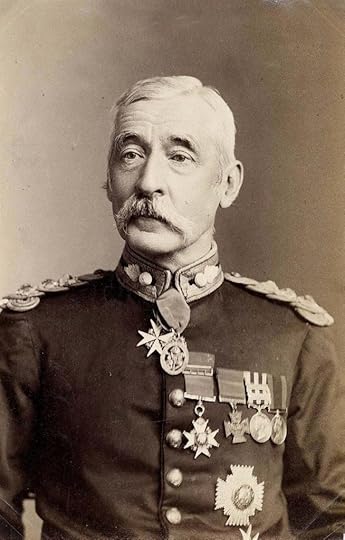

Desanges, Louis William; Captain (later General Sir) Dighton MacNaghten Probyn, 2nd Punjab Cavalry, at the Battle of Agra NamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkPark, James (Gnr) Bengal ArtilleryLucknow14-22 November 1857Courage in ChaosPaton, John (Sgt) 93rd HighlandersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIIPearson, James (Pte) 86th FootJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsPearson, John (Pte) 8th HussarsGwalior17 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IIPhillipps, Everard (Ens) 11 BNIDelhi30 May 1857 to 18 September 1857Returns for Delhi 15th – 22nd of SeptemberPrendergast, Harry (Lt) Madras EngineersMandsaur21 November 1857The Path Before Him Always BrightProbyn, Dighton (Capt) 2nd Punjab CavalryAgra1857 to 1858For Distinguished Gallantry, Captain Dighton Probyn, VCPurcell, John (Pte) 9th LancersDelhi19 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsPye, Charles (Sgt Maj) 53rd FootLucknow17 November 1857Courage in Chaos IVR. Frederick Roberts

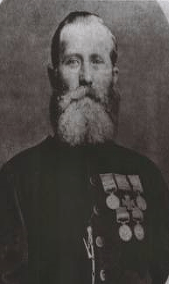

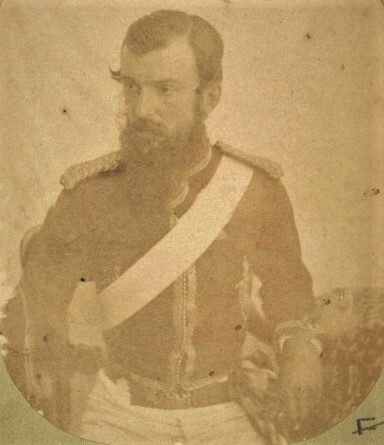

Frederick Roberts William Rennie

William Rennie George Renny

George Renny Surgeon Herbert Reade at DelhiNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkRaynor, William (Lt) Bengal Veterans EstablishmentDelhi11 May 1857And God Shall Wipe All Tears from their Eyes IReade, Herbert (Surg) 61st FootDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraveryRennie, William (Lt Adjt) 90th FootLucknow21-25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIRenny, George (Lt) Bengal Horse ArtilleryDelhi16 September 1857Acts of BraveryRichardson, George (Pte) 34th FootKewane (Trans-Gogra)27 April 1859 Roberts, Frederick (Lt, DAQMG, ADC) Bengal Horse ArtilleryKhodagunge2 January 1858The Long Life of Lord Roberts, VCRoberts, James (Pte) 9th LancersBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrRobinson, Edward (Able Seaman) Naval BrigadeLucknow13 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IIIRoddy, Patrick (Ens) Bengal Army, unattachedKuthirga27 September 1858 Rodgers, George (Pte) 71st FootMarar16 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IRosamund, Matthew (Sgt Maj) 37th BNIBenares4 June 1857Humble Beginnings – The Three VCs of BenaresRushe, David (TSM) 9th LancersLucknow19 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IVRyan, John (Pte) 1st Madras European FusiliersLucknow26 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIRyan, Miles (D) 1st Bengal European FusiliersDelhi14 September 1857Acts of Bravery

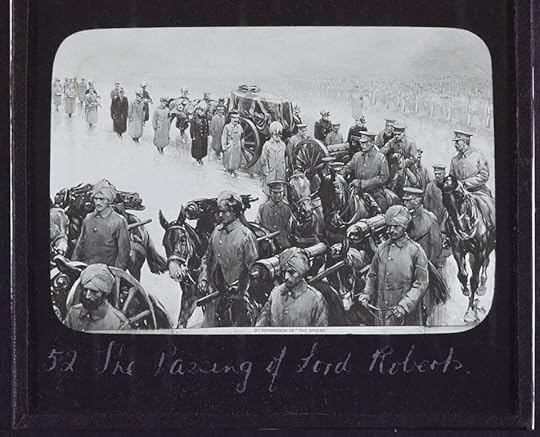

Surgeon Herbert Reade at DelhiNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkRaynor, William (Lt) Bengal Veterans EstablishmentDelhi11 May 1857And God Shall Wipe All Tears from their Eyes IReade, Herbert (Surg) 61st FootDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraveryRennie, William (Lt Adjt) 90th FootLucknow21-25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIIRenny, George (Lt) Bengal Horse ArtilleryDelhi16 September 1857Acts of BraveryRichardson, George (Pte) 34th FootKewane (Trans-Gogra)27 April 1859 Roberts, Frederick (Lt, DAQMG, ADC) Bengal Horse ArtilleryKhodagunge2 January 1858The Long Life of Lord Roberts, VCRoberts, James (Pte) 9th LancersBulandshahr28 September 1857The Seven VCs of BulandshahrRobinson, Edward (Able Seaman) Naval BrigadeLucknow13 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IIIRoddy, Patrick (Ens) Bengal Army, unattachedKuthirga27 September 1858 Rodgers, George (Pte) 71st FootMarar16 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IRosamund, Matthew (Sgt Maj) 37th BNIBenares4 June 1857Humble Beginnings – The Three VCs of BenaresRushe, David (TSM) 9th LancersLucknow19 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IVRyan, John (Pte) 1st Madras European FusiliersLucknow26 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIRyan, Miles (D) 1st Bengal European FusiliersDelhi14 September 1857Acts of Bravery The Passing of Lord Roberts

The Passing of Lord RobertsAbbreviations:

ADC – Aide de CampAsst. Surg. – Assistant SurgeonBdr – BombardierBglr – BuglerC/Sergt – Colour SergeantCapt – CaptainCpl – CorporalD – DrummerDAC – Deputy Assistant CommissaryDAQMG – Deputy Assistant Quarter Master GeneralEns – EnsignGnr – GunnerL/Cpl – Lance CorporalLt – LieutenantLt Adjt – Lieutenant AdjutantMaj – MajorPte – PrivateQMS- Quartermaster SergeantSgt – SergeantSgt Maj – Sergeant MajorSurg – SurgeonTptr – TrumpeterTSM – Troop Sergeant MajorVolunt. – VolunteerVCs of 1857-1859: S-Y

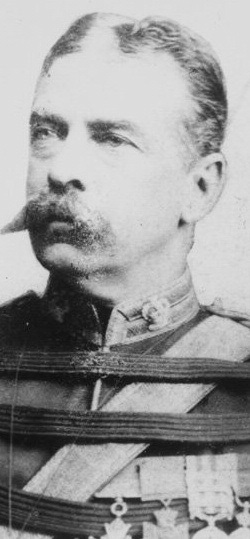

Robert Shebbeare

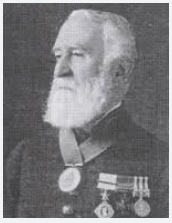

Robert Shebbeare John Sinnott

John Sinnott William Sutton

William Sutton Robert Shebbeare (seated, 2nd right) with officers of the 15th Punjab Regiment (Felice Beato, ca 1858)SNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkSalkeld, Philip (Lt) Bengal Sappers and MinersDelhi14 September 1857The 14th of SeptemberSalmon, Nowell (Lt) Naval BrigadeLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIIShaw, Same (Pte) Rifle BrigadeLucknow13 June 1858 Shebbeare, Robert (Lt) 60th BNI, 15th Punjab RegimentDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraverySimpson, John (QMS) 42nd HighlandersFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadSinnott, John (L/Cpl) 84th FootLucknow6 October 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVSleavon, Michael (Cpl) Royal EngineersJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsSmith, Henry (L/Cpl) 52nd FootDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraverySmith, John (Sgt) Bengal Sappers & MinersDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraverySmith, John (Pte) 1st Madras European FusiliersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in ChaosSpence, David (TSM) 9th LancersShumsabad17 January 1858David Spence, VCSpence, Edward (Pte) 42nd HighlandersFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadStewart, William (Capt) 93rd HighlandersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IISutton, William (Bglr) 60th RiflesDelhi2 August 1857 to 13 September 1857Acts of BraveryT

Robert Shebbeare (seated, 2nd right) with officers of the 15th Punjab Regiment (Felice Beato, ca 1858)SNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkSalkeld, Philip (Lt) Bengal Sappers and MinersDelhi14 September 1857The 14th of SeptemberSalmon, Nowell (Lt) Naval BrigadeLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IIIShaw, Same (Pte) Rifle BrigadeLucknow13 June 1858 Shebbeare, Robert (Lt) 60th BNI, 15th Punjab RegimentDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraverySimpson, John (QMS) 42nd HighlandersFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadSinnott, John (L/Cpl) 84th FootLucknow6 October 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVSleavon, Michael (Cpl) Royal EngineersJhansi3 April 1858Holding the Course and Saving Lives – the Jhansi VCsSmith, Henry (L/Cpl) 52nd FootDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraverySmith, John (Sgt) Bengal Sappers & MinersDelhi14 September 1857Acts of BraverySmith, John (Pte) 1st Madras European FusiliersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in ChaosSpence, David (TSM) 9th LancersShumsabad17 January 1858David Spence, VCSpence, Edward (Pte) 42nd HighlandersFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadStewart, William (Capt) 93rd HighlandersLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos IISutton, William (Bglr) 60th RiflesDelhi2 August 1857 to 13 September 1857Acts of BraveryT Edward Thackeray

Edward Thackeray James Thompson

James Thompson John Tytler

John Tytler Major Tombs Saving Lieutenant Hills at DelhiNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkThackeray, Edward (2nd Lt) Bengal Sappers & MinersDelhi16 September 1857Acts of BraveryThomas, Jacob (Bdr) Bengal ArtilleryLucknow27 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVThompson, Alexander (L/Cpl) 42nd HighlandersFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadThompson, William (Pte) 60th RiflesDelhi9 July 1857Spirited DaringTombs, Henry (Maj) Bengal Horse ArtilleryDelhi9 July 1857Spirited DaringTravers, James (Col) 2nd Bengal Native Infantry; Bhopal ContingentIndoreJuly 1857Not One Shall StandTurner, Samuel (Pte) 60th RiflesDelhi19 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsTytler, John (Lt) 66th BNIChoorpoorah10 February 1858In the Hills of KumaonW-Y

Major Tombs Saving Lieutenant Hills at DelhiNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkThackeray, Edward (2nd Lt) Bengal Sappers & MinersDelhi16 September 1857Acts of BraveryThomas, Jacob (Bdr) Bengal ArtilleryLucknow27 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IVThompson, Alexander (L/Cpl) 42nd HighlandersFort Ruiya15 April 1858The Brave and the DeadThompson, William (Pte) 60th RiflesDelhi9 July 1857Spirited DaringTombs, Henry (Maj) Bengal Horse ArtilleryDelhi9 July 1857Spirited DaringTravers, James (Col) 2nd Bengal Native Infantry; Bhopal ContingentIndoreJuly 1857Not One Shall StandTurner, Samuel (Pte) 60th RiflesDelhi19 June 1857For Valour – The Delhi VCsTytler, John (Lt) 66th BNIChoorpoorah10 February 1858In the Hills of KumaonW-Y John Watson

John Watson Richard Wadeson

Richard Wadeson Thomas Young

Thomas Young Private Ward Saving Lieutenant Havelock, LucknowNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkWadeson, Richard (Lt) 75th FootDelhi17 July 1857Spirited DaringWaller, George (C/Sgt) 60th RiflesDelhi14 September 1857, 18 September 1857Acts of BraveryWaller, William (Lt) 25th Bombay Light InfantryGwalior20 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IIIWard, Henry (Pte) 78th HighlandersLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIWard, Joseph (Sgt) 8th HussarsGwalior17 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IIWatson, John (Lt) 1st Punjab CavalryLucknow14 November 1857Four Extraordinary MenWilmot, Henry (Capt) Rifle BrigadeLucknow11 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IIWhirlpool, Frederick (Pte) 3rd Bombay European RegimentJhansi; Lohari3 April 1858, 2 May 1858The Man Without a Past, Frederick Whirlpool, VCWood, Evelyn (Lt) 17th LancersSinwaho19 October 1858 Young, Thomas (Lt) Naval BrigadeLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos III

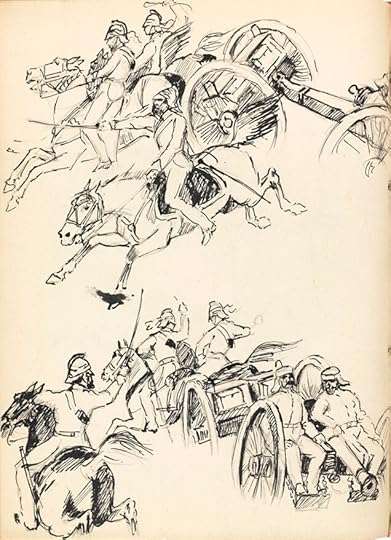

Private Ward Saving Lieutenant Havelock, LucknowNamePlace of ActionDate of actionLinkWadeson, Richard (Lt) 75th FootDelhi17 July 1857Spirited DaringWaller, George (C/Sgt) 60th RiflesDelhi14 September 1857, 18 September 1857Acts of BraveryWaller, William (Lt) 25th Bombay Light InfantryGwalior20 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IIIWard, Henry (Pte) 78th HighlandersLucknow25 September 1857The Path of Duty is the Way to Glory IIWard, Joseph (Sgt) 8th HussarsGwalior17 June 1858A Few Astonishing Men Part IIWatson, John (Lt) 1st Punjab CavalryLucknow14 November 1857Four Extraordinary MenWilmot, Henry (Capt) Rifle BrigadeLucknow11 March 1858The Valorous Twelve – Part IIWhirlpool, Frederick (Pte) 3rd Bombay European RegimentJhansi; Lohari3 April 1858, 2 May 1858The Man Without a Past, Frederick Whirlpool, VCWood, Evelyn (Lt) 17th LancersSinwaho19 October 1858 Young, Thomas (Lt) Naval BrigadeLucknow16 November 1857Courage in Chaos III Bengal Horse Artillery

Bengal Horse ArtilleryAbbreviations

ADC – Aide de CampAsst. Surg. – Assistant SurgeonBdr – BombardierBglr – BuglerC/Sergt – Colour SergeantCapt – CaptainCpl – CorporalD – DrummerDAC – Deputy Assistant CommissaryDAQMG – Deputy Assistant Quarter Master GeneralEns – EnsignGnr – GunnerL/Cpl – Lance CorporalLt – LieutenantLt Adjt – Lieutenant AdjutantMaj – MajorPte – PrivateQMS – Quartermaster SergeantSgt – SergeantSgt Maj – Sergeant MajorSurg – SurgeonTptr – TrumpeterTSM – Troop Sergeant MajorVolunt. – VolunteerJanuary 3, 2026

The Brave and the Dead

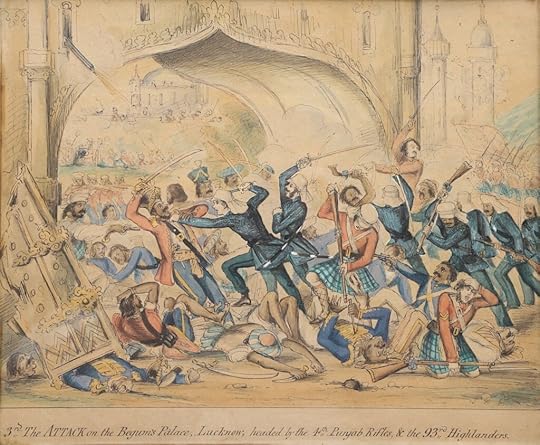

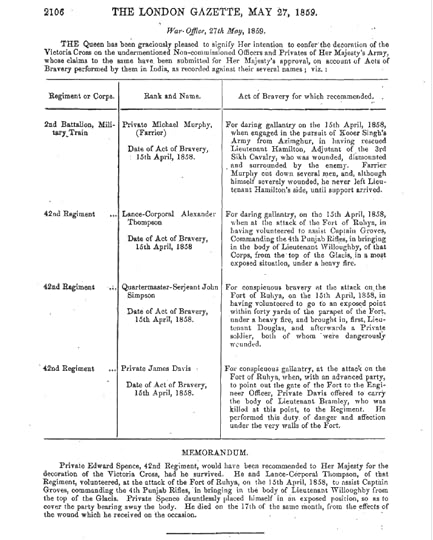

For the failed action at Ruiya, four Victoria Crosses were awarded. A fifth recipient, killed on that day, would eventually receive the recognition he deserved, half a century later. No posthumous VCs were awarded during the Indian Mutiny – due to the regulations surrounding the Victoria Cross at the time of the mutiny that insisted the Cross could only be given to living recipients, entries in the London Gazette stated simply “would have been recommended to Her Majesty for the decoration of the Victoria Cross, had he survived.” When King Edward VII, in 1907, changed the Royal Warrant to permit posthumous awards, 50 years after the Indian Mutiny, four such VCs were presented and an amended entry was published in the London Gazette for not only Ensign Everard Aloysius Lisle Phillips (Delhi), Lieutenant Duncan Charles Home (Bengal Engineers, Delhi), Lieutenant Philip Salkeld (Bengal Engineers, Delhi) but also Private Edward Spence (Fort Ruiya). The only VC to escape the posthumous clause was awarded to Cornet Bankes at Lucknow, although Bankes never wore his Cross – the recommendation was made when Bankes was still alive and provisionally conferred by Sir Colin Campbell; Queen Victoria personally ensured it was confirmed, and Bankes’ mother would subsequently receive the VC in the mail. As the recommendation was processed before Bankes died, it could not be blocked by stipulations of the Warrant current at the time.

For Ruiya, the five men singled out for the Victoria Cross were:

Captain William Cafe – 4th Punjab Rifles

Quartermaster-Sergeant John Simpson – 42nd Regiment of Foot

Lance-Corporal Alexander Thompson – 42nd Regiment of Foot

Private James Davis – 42nd Regiment of Foot

Private Edward Spence – 42nd Regiment of Foot

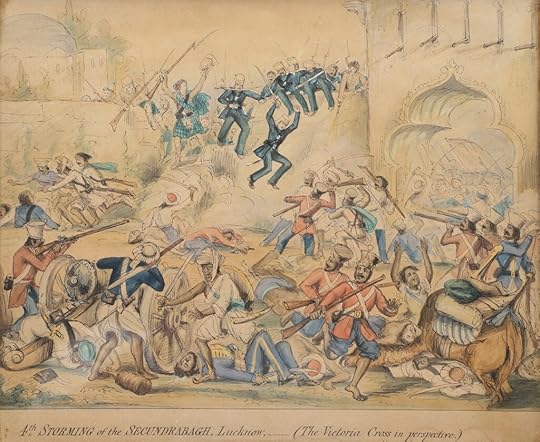

Three of the crosses were awarded for what adds up to being the same action, and that was rescuing not Lieutenant Edward Cotgrave Parr Willoughby, but the attempt to retrieve his lifeless body. The action would see one man seriously wounded and cost the other his life.

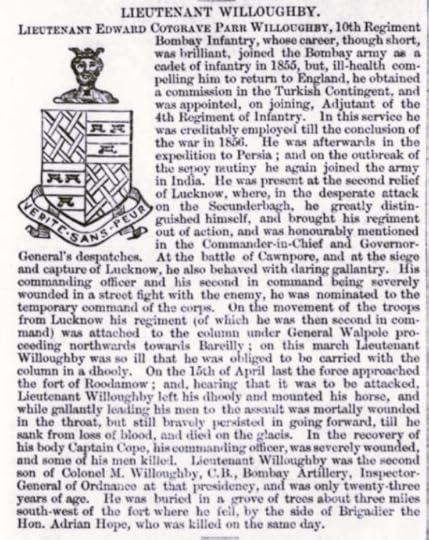

Lieutenant Edward Cotgrave Parr Willoughby was the second son of the illustrious Major-General Michael Francklin Willoughby (CB), who had served in India with the Royal Artillery, mostly in Gujarat and the Southern Maratha Country in the 1820s. He was present at the Capture of Aden in 1839 and then later commanded an artillery battery at Hyderabad. He ended his career on a less war-like path, as Principal Commissary of Ordnance and Inspector General of Ordnance at Bombay. During the Mutiny, he was appointed to the Staff of the India Office as Deputy-Inspector General of Stores and, in 1858, as Inspector. All his sons who survived to adulthood (three out of seven) would serve in India, and while it is tempting to think that one of them was responsible for the blowing up of the Delhi Magazine, this is a fallacy. George Willoughby was the son of a solicitor and not the major-general. However, George Willoughby too served in the artillery, and like the Major-General, had attended Addiscombe. If similarities must continue, both George and Edward would die in the Indian Mutiny holding the rank of lieutenant. We now return to the Major-General’s son.

Lieutenant Edward Willoughby was born in Pune in 1834. He was sent to England for his education and arrived in India in 1855 with a posting to the Bombay Army. The London Illustrated News for July 17, 1858, published a detailed obituary, detailing a young man’s very short but very active life.

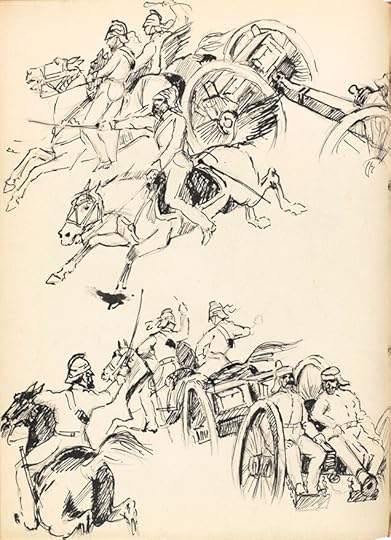

Six illustrations were recently sold at auction and titled, “Six scenes in the life of Lieutenant Edward Cotgrave Parr Willoughby, 4th Punjab Rifles (killed during the Indian Mutiny 1858) aged 23. 2nd Son of Major General Michael Franklin Willoughby C.B., Inspector General of Military Stores for India.” It is unclear who the illustrator was but it is presumed it was a member of his family.

Willoughby was well-liked by his adopted regiment, the 4th Punjabis, although he had only joined on 7 November 1857, shortly before the Relief of Lucknow. He would temporarily be left in charge of the regiment when the senior officers were wounded, firstly at Lucknow and then at the Battle of Cawnpore. There is no doubt about the fight in the young man. Although suffering from a sore throat and obliged to be carried in a doolie on the march to Ruiya, with the battle imminent, he insisted on joining his regiment, much against his own presentiments. Wrote Fairweather:

“Curiously enough, although as cool as anything in action, he was despondent when ill and that morning, particularly so. When he heard there was the prospect of a fight, he jumped out of his doolie in the highest spirits… So he went to fight in his slippers just as he had come out of his doolie. However, he remarked to me, ‘ I wish I could get a flesh wound, for I feel almost sure that when I do get a wound, it will be mortal.’ ” It was the last time Fairweather would speak to Willoughby.

So Willoughby joined the 4th Punjabis in front of Ruiya Fort.

Early on in the fight, Willoughby was shot across the collarbone (other accounts say he was shot in the throat -as it was Fairweather who dressed his body for his funeral, we can take Fairweather at his word regarding the nature of the injury, and the shot was not in the throat directly). He sat down on the glacis, where Captain Cafe passed him and ordered him to retire to the field hospital. Unfortunately, Willoughby never regained his feet and bled to death where he sat. Here, Cafe passed him when the 4th Punjabis retreated.

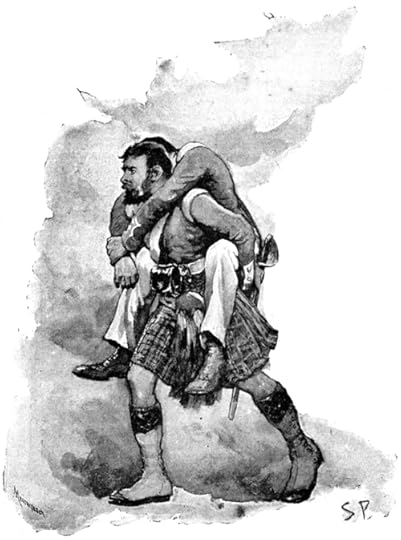

Cafe called to his men to pick up Willoughby’s body and bring it back with them – it was very much the honour of the Punjabis to never leave their wounded and dead behind, so the order was not unusual in the circumstances; however, still being under heavy fire from the fort, they were unable to pick him up. Cafe now called on volunteers – immediately, two men of the 42nd, Lance-Corporal Thompson and Private Spence, and three Punjabis stepped up and together “they all went towards the body and dragged it back by its feet into cover.”

“In doing this one of the 4th Punjabi Infantry sepoys was killed and one of the Highlanders had his thigh bone broken; as he was lying on the ground, he called out, ‘ You are surely not going to leave me here,’ and Cafe again went out and helped the man in but not before his left arm was smashed above the elbow by a bullet.”

Willoughby’s body was not the only one retrieved from the field that fatal day.

Quartermaster Simpson of the 42nd, on hearing the retreat, immediately rushed back to the ditch and brought back Lieutenant Douglas; he then returned and brought out a wounded private of the 42nd. The story of Simpson’s bravery has, in part, been embellished in certain accounts ( according to Malleson, he saved seven men from the ditch – Malleson also gave him credit for saving Lieutenant Bramley – this can be taken as a mutiny exaggeration and considering the circumstances, while nobly intended, rather fanciful).

The two Punjabis who survived recovering Willoughby’s body received the Order of Merit.

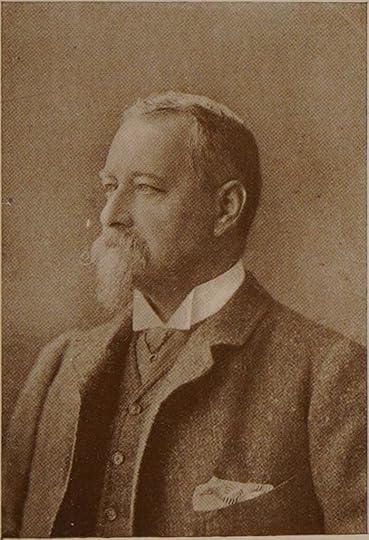

Captain William Martin Cafe – 4th Punjab Rifles

William Martin Cafe was born in London on 23 March 1826 to Henry Smith Cafe, an auctioneer and his wife Sarah (née Waine). It would appear the army held some appeal to the young man, for on 11 June 1842, he was already in India, serving as an ensign to the 56th Bengal Native Infantry. Promotion was rather swift, at least at the start, for by 12 April 1843, Cafe was a lieutenant. However, he had already seen war, for 1843 was the same year of the Gwalior Campaign, and he served at the action at Maharajpur for which he received a Gwalior Star.

As Captain Cafe, in 1849, he then served throughout the Punjab Campaign, including Sadulapur, Chillianwala, and Gujerat. Where Cafe was when his regiment, the 56th BNI, mutinied at Cawnpore is unclear, as quite obviously, he was not with them. The next time we hear of Captain Cafe, he had joined the 4th Punjab Rifles. He fought not only at Delhi but also at Lucknow at the Relief in 1857 and the retaking of the city in March 1858.

His citation in the London Gazette is as follows:

For bearing away, under a heavy fire, with the assistance of Privates Thompson, Crowie, Spence, and Cook, the body of Lieutenant Willoughby, lying near the ditch of the Fort of Ruhya, and for running to the rescue of Private Spence, who had been severely wounded in the attempt. (The London Gazette of 17 February 1860, Numb. 22357, p. 557)

Ruiya put an end to Cafe’s association with India for quite some time – the wound was so severe that he was obliged to return home on sick certificate from July 1858 until 1860. Cafe was gazetted quite late and received his VC at a private investiture in India in December the same year.

When Cafe returned to India, he joined the Adjutant General’s Department and would spend the rest of his career on the Staff before retiring in 1894, with his final rank of general. He died in 1906 at his home in Kensington and is buried in Brompton Cemetery. His medals, including his VC (Gwalior Star ‘Maharajpoor’, Punjab Medal 1848-49 with clasps Chilianwala, Goojerat; Indian Mutiny Medal 1857-58 with clasps Delhi, Relief of Lucknow, Lucknow), are held by the National Army Museum in Chelsea.

John Simpson was born on 29 January 1826 at West Church Parish Edinburgh, the son of James Simpson a general grocer and his wife, Mary. He enlisted in the 42nd Regiment on 8 June 1843 and served with his regiment in Crimea. Simpson was present at the Battle of the Alma, Balaclava and the assaults on the Redan at Sebastopol on both 18 June and 8 September. As Quartermaster-Sergeant (7 Sept, 1855), Simpson served through the Indian Mutiny (Mutiny Medal, one clasp, ‘Lucknow’). Following the mutiny, he received a commission as Quartermaster of the 42nd in India in 1859.

When Brigade Depots were formed in 1873, Simpson was appointed Quartermaster of the 55th Brigade Depot at Fort George, Madras. He also served in the 2nd Ashanti War. In 1874, Simpson transferred to the 58th Brigade Depot at Stirling and in 1879, to the Perth Militia, returning to the Black Watch in 1881 as Quartermaster of the 3rd Battalion.

Simpson was made an honorary Captain in 1883 and retired as an honorary Major in 1883, the same year he was gazetted as Quartermaster for the 2nd Perth Highland Volunteers. Upon his retirement, his Good Service Pension amounted to £ 50. As for his Victoria Cross, it must have been with mixed feelings, for it was presented to him by Brigadier General Robert Walpole at Bareilly in 1860. Major John Simpson died on 27 October 1884, aged just 58, and was buried with full military honours by the 2nd Perthshire and the 3rd Battalion Black Watch in attendance. His grave is at Balbeggie Churchyard, St. Martin’s, near Perth, Scotland. The question is, what happened to his medals? The site, http://www.blackwatch.50megs.com/ offers the following explanation:

According to the Red Hackle of July 1924, Simpson’s medals formed a prize centre piece in the collection of Medals of the Black Watch formed by Captain John Stewart and which was then in the Officers’ Mess of the 1st Btn at Aldershot. Now, according to one of the major VC websites, the medal is located in the County Museum of Natural History in Los Angeles. However, no one can explain how it ended up in the United States and why the VC remains outside his native land.

Lance-Corporal Alexander Thompson – 42nd Regiment of Foot

Unfortunately, we know little of the early life of Alexander Thompson – he was born in 1824 in Tolbooth Parish, Edinburgh, Scotland; his father, John, was a mason by profession. In 1842, Alexander enlisted in the 42nd Regiment at Stirling, citing his profession as a weaver. Like Simpson, he served in the Crimean War and in 1855 was promoted to corporal. This, however, was short-lived, for seven months later, in May 1856, he was demoted to private. It would seem Thompson was determined to turn himself around, and by the time Ruiya came about, he was Lance Corporal. His career is a series of promotions and a short demotion:

Corporal – 21 July 1858

Lance-Sergeant – 24 September 1859

Reduced to Corporal – 10 February 1860

VC investiture at Bareilly, 7 April 1860, under the auspices of Brigadier-General Robert Walpole

Lance-Sergeant – 26 January 1861

Sergeant – 3 February 1861

Sergeant Thompson was discharged on medical grounds in July, 1863 at Netley Military Hospital. For the remainder of his life, he worked as a twister, a grocer, a timekeeper and a labourer. He died in 1880 in Perth, Scotland. Besides his Victoria Cross, at the time of his death, he had an impressive set of medals that resides at the Black Watch Museum – Crimea Medal 1854-56 with clasps Alma, Balaklava, Sebastopol; Indian Mutiny Medal 1857-58 with clasp Lucknow; Turkish Crimea Medal 1854-55.

James Davis was born James Davis Kelly in Canongate Parish, Edinburgh in February 1835 to William Kelly, a labourer and his wife, Bridget. James’ career as a shoemaker was likely not quite as interesting as enlisting in the Black Watch in 1852, but he did so as James Davis, dropping his last name, Kelly. It does not appear that promotion was written on his cards for when he was discharged at Portsmouth in 1873, it was as a private. What became of him after is not known, but James Davis is the only man who left his own account of the Ruiya affair, as related to the Strand Magazine, in March 1891.

“I belonged to the Light Company under the command of Captain MacLeod. We got orders to lie down under some trees for a short time. Two Engineer officers came up and asked for some men to come with them to see where they could make a breach with artillery. I was one who went. There was a small garden ditch under the walls of the fort, not high enough to cover our heads. After a short time, the officers left. I was on the right of the ditch with Lieutenant Alfred Jennings Bramley of Tunbridge Wells, as brave a young officer as ever drew a sword, and saw a large force coming out to cut us off. He said, ‘Try and shoot the leader. I will run down and tell McLeod.’ The leader was shot, by whom I do not know. I never took credit for shooting anyone. Before poor Bramley got down, he was shot in the temple, but not dead. He died during the night.

The captain said, ‘ We can’t leave him. Who will take him out?’ I said, ‘I will.’

“I ran across the open space.”

“I ran across the open space.”The fort was firing hard all the time. I said, ‘Eadie, give me a hand. Put him on my back.’ As he was doing so, he was shot in the back of the head, knocking me down, his blood running down my back. A man crawled over and pulled Eadie off. At the time, I thought I was shot. The captain said, ‘We can’t lose anymore lives. Are you wounded?’ I said, ‘I don’t think I am.’ He said, ‘Will you still take him out?’ I said, ‘Yes.’

He was such a brave young fellow that the company loved him. I got him on my back again and told him to take tight around the neck. I ran across the open space. During the time, his watch fell out; I did not like to leave it, so I sat down and picked it up, all the time under a heavy fire. There was a man named Dods, who came and took him off my back. I went back through the same fire and helped to take up the man Eadie. I returned from my rifle, and firing a volley, we all left. It was a badly managed affair altogether.”

Like Simpson and Thompson, Davis received his VC from the man who cost Bramley his life. Davis died in 1893 and lies buried at North Merchiston Cemetery in Edinburgh in an unmarked grave. His VC resides in the Lord Ashcroft Collection. His medals, besides the VC, included:

Turkish Crimea Medal ( 1855-56 )

Crimea Medal ( 1854-56 ) – 3 clasps: “Alma” – “Balaclava” – “Sebastopol”

Indian Mutiny Medal ( 1857-58 ) – 1 clasp: “Lucknow”

Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Chetham McLeod, GCB; The Black Watch Castle & MuseumPrivate Edward Spence – 42nd Regiment of Foot

Lieutenant Colonel Sir John Chetham McLeod, GCB; The Black Watch Castle & MuseumPrivate Edward Spence – 42nd Regiment of Foot “Private Edward Spence, 42nd Regiment, would have been recommended to Her Majesty for the decoration of the Victoria Cross, had he survived. He and Lance-Corporal Thompson, of that Regiment, volunteered, at the attack of the Fort of Ruhya, on the 15th April, 1858, to assist Captain Groves, commanding the 4th Punjab Rifles, in bringing in the body of Lieutenant Willoughby from the top of the Glacis. Private Spence dauntlessly placed himself in an exposed position, so as to cover the party bearing away the body. He died on the 17th of the same month, from the effects of the wound which he received on the occasion. (The London Gazette of 27 May 1859, Numb. 22268, p. 2106)

VICTORIA CROSS. Errata in the London Gazette of Friday, May 27, 1859.

In the notifications of the Acts of Bravery performed by Lance Corporal Alexander Thompson and the late Private Edward Spence, of the 42nd Regiment, For Captain Groves, commanding the 4th Punjaub Rifles, Read Captain Cafe, commanding the 4th Punjaub Rifles. (The London Gazette of 21 October 1859, Numb. 22318, p. 3793) War Office, January 15, 1907.

The King has been graciously pleased to approve of the Decoration of the Victoria Cross being delivered to the representatives of the undermentioned Officers and men who fell in the performance of acts of valour, and with reference to whom it was notified in the London Gazette that they would have been recommended to Her late Majesty for the Victoria Cross had they survived:– London Gazette, 27th May, 1859. “Private Edward Spence, 42nd Regiment, would have been recommended to Her Majesty for the decoration of the Victoria Cross had he survived. He and Lance-Corporal Thompson, of that Regiment, volunteered at the attack of the Fort of Ruhya, on the 15th April, 1858, to assist Captain Cafe, commanding the 4th Punjab Rifles, in bringing in the body of Lieutenant Willoughby from the top of the Glacis. Private Spence dauntlessly placed himself in an exposed position so as to cover the party bearing away the body. He died on the 17th of the same month from the effects of the wound which he received on the occasion.” (The London Gazette of 15 January 1907, Numb. 27986, p. 325)

Born in Dumfries, Scotland, on 28 December 1830, and, after enlisting in the Black Watch, like his colleagues, would serve in the Crimean War. As we know so little about Spence, I have included his citation not only from 1859 but 1907. The Victoria Cross, after a six-month hunt for relations, was finally handed over to the son of his father’s cousin – it now resides in the Black Watch Museum in Perth, to whom it was anonymously donated. Spence lies buried at Ruiya.

“As the four men were nearing the edge of the jungle with the body (of Willoughby) Captain Cafe turned to see if Spens (Spence) was safe and following, but saw him kneeling on the edge of the ditch and beckoning with his hand. Desiring Thompson to go on to the dhoolie with the body, Cafe turned and went back to Spens, and found that he was wounded through the thigh and unable to get up. While standing beside him and encouraging him to make an effort to rise, Captain Cafe saw one of the enemy preparing to take a shot either at himself or Spens through an embrasure, so quickly stooping down, he picked up Spens’ rifle and shot the man. At last Spens, making an effort, got upon his feet, when Captain Cafe, giving him the support of his left arm, and carrying the rifle and the feather bonnet in his right hand, retired slowly with the wounded man. Before they could reach the shelter of the jungle, a bullet passed through Cafe’s arm above the elbow, the arm upon which Spens was leaning, but he continued to give the support of his wounded arm until he put Spens in a place of safety. Spens was morally wounded (the femoral artery cut through) and died in a few minutes, and Captain (now General) Cafe has almost lost the use of his left arm, the result of the wound received that day.” (Munro)

And all this misery for a man who refused to reconnoitre.

Sources:

Gordon-Alexander, Lieut. Col. W. – Recollections of a Highland Subaltern (London: Edward Arnold, 1898)

Malleson, Col. G.B. – History of the Indian Mutiny, Vol. II (London: William H. Allen & Co., 1879)

Munro, Surgeon-General – Reminiscences of Military Service with the 93rd Highlanders ( London: Hurst & Blackett Publishers, 1883)

Munro, Surgeon General – Records of Service and Campaigning in Many Lands, Vol II (London: Hurst & Blackett Ltd., 1887)

Russell, William Howard– My Diary in India, Vol. I (London: Routledge, Warne & Routledge, 1860)

Wright, William – Through the Indian Mutiny – The Memoirs of James Fairweather, 4th Punjab Native Infantry, 1857-58 (Spellmount Military Memoirs, 2011)

Links:

https://vcgca.org/

https://www.victoriacross.org.uk/

https://www.victoriacross.org.uk/

http://www.blackwatch.50megs.com/

Strand Magazine, Volume 1, Issue 3, March 1891

https://auctionet.com/en/events/705-militaria-medals-coins/163-a-fascinating-set-of-six-studies-of-scenes-in-the-life-of-lt-edward-cotgrave-parr-willoughby-whose-career-though-short-was-brilliant-and-whose-death-resulted-in-the-award-of-three-victoria-crosses – Six scenes in the life of Lieutenant Edward Cotgrave Parr Willoughby, 4th Punjab Rifles (killed during the Indian Mutiny 1858) aged 23. 2nd Son of Major General Michael Franklin Willoughby C.B. Inspector General of Military Stores for India.

January 2, 2026

Recriminations Fail

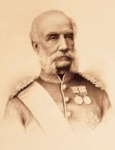

Sir Robert Walpole

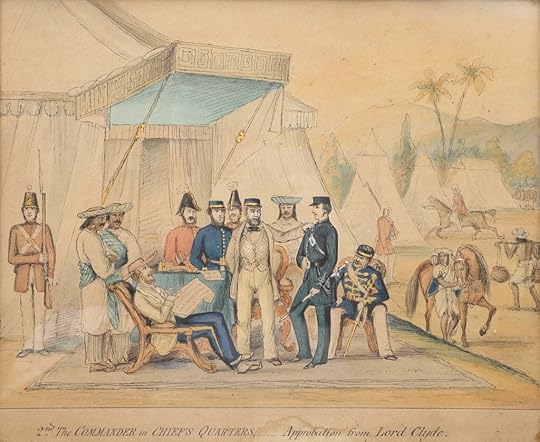

Sir Robert WalpoleWalpole’s defeat at Ruiya did not go unnoticed. His account of the affair raised eyebrows throughout the military establishment. It garnered a cold response from Sir Colin Campbell and an even colder one from the office of Lord Canning, who heaped honour on Adrian Hope and carefully avoided any praise of Walpole.

No. 38.

No. 102 of 1858.

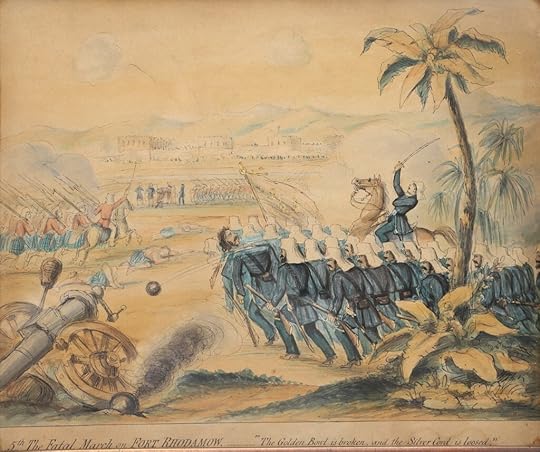

THE Right Honorable the Governor-General of India is pleased to direct the publication of the following despatch, from the Deputy Adjutant- General of the Army, No. 257 A, dated 20th April, 1858, forwarding copy of a report from Brigadier-General R. Walpole, Commanding Field Force, detailing his operations against and capture of the fort of Rooya, on the 15th instant.

His Lordship participates in the grief expressed by His Excellency the Commander-in-Chief at the heavy loss which the British army has sustained in the death of that most admirable officer, Brigadier the Honourable A. Hope, whose very brilliant services he had had the gratification of publicly recognizing in all the operations for the relief and the final capture of Lucknow. No more mournful duty has fallen upon the Governor-General in the course of the present contest than that of recording the premature death of this distinguished young commander.

The Governor-General shares also in the regret of the Commander-in-Chief at the severe loss of valuable lives which has attended the operations against the fort of Rooya.

R.J H. BIRCH, Colonel, Secretary, Government of India, Military Department, with the Governor-General.

Walpole’s dispatch was rightly seen by many as suspicious, neglecting outright to mention he had been strenuously advised to reconnoitre by not only Brind but Haggart and Hope. He had dismissed outright the information given to him by the trooper of Hodson’s Horse, who had no reason to lie, in favour of two guides who most likely had every reason to lead him astray. To make matters worse, Walpole had not made use of his artillery, his engineers or his sappers. When under fire, he had been unable to make clear decisions, had acted irrationally and with anger, and, above all, had failed to listen to the very men who could have won him an astonishingly easy victory.

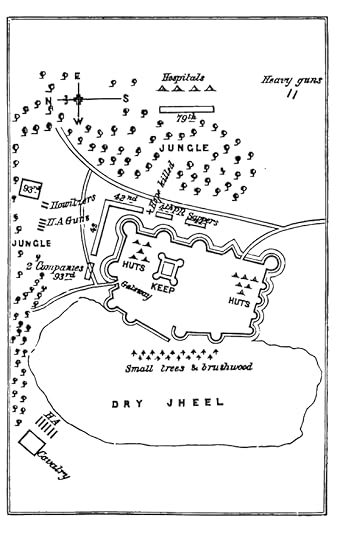

As it turned out, the next morning, when the British entered Ruiya Fort, it was even clear to the regimental surgeon of the 93rd, Munro, just how simple the task would have been. The south side of the fort had no defences at all except for a narrow grove of trees, a shallow and practically empty ditch, and a low, broken wall. It was, in fact, so open that the cavalry could have ridden in and taken care of the operation themselves. To make matters worse, James Hills-Jones (VC), who happened to be present with Tombs’ battery, had seen Nirpat Singh’s horsemen riding in and out of the place during the entire battle. This was corroborated by another officer, Sam Browne (later General Sir Samuel James Browne, VC, GCB, KCSI). He had taken it on himself to reconnoitre the fort early the next morning with his cavalry and found a breach in the wall so wide his regiment could have ridden in “three abreast.” Adrian Hope and the others had lost their lives for nothing. As William Russell, the Times correspondent, accurately pointed out, “Walpole seems to have made the attack in a very careless, unsoldierly way…”

The condemnation was severe, and although this particular passage was written 20 years after the fact, it reflected the thoughts and feelings of many who served under Robert Walpole. The campaign, as Malleson rightly pointed out, was not a difficult one and very little was asked of Walpole. “To carry it to a successful issue, then, demanded no more than the exercise of vigilance, of energy, of daring—qualities the absence of which from a man’s character would stamp him as unfit to be a soldier.

Walpole, unhappily, possessed none of these qualities. Of his personal courage, no one ever doubted, but as a commander, he was slow, hesitating, and timid. With some men, the power to command an army is innate. Others can never gain it. To this last class belonged Walpole.

He never was, he never could have been, a general more than in name. Not understanding war, and yet having to wage it, he carried it on in a blundering and haphazard manner, galling to the real soldiers who served under him, detrimental to the interests committed to his charge. If the campaign offered no difficulties, it may be urged, surely any man, even a Walpole, might have carried it to a successful issue. Thus, to brand a commander with incapacity when the occasion did not require capacity is as unnecessary as ungenerous!

It might be so, indeed, if the campaign, devoid of difficulty as it was, had not been productive to of disaster. But the course of this history will show that, that though there ought to have been no difficulties, Walpole, by his blundering and obstinacy, created them, and, worse than all, he, by a most unnecessary — I might justly say by a wanton — display of those qualities sacrificed the life of one of the noblest soldiers in the British army — sent to his last home, in the prime of his splendid manhood, in the enjoyment of the devotion of his men, of the love of his friends, of the admiration and well-placed confidence of the army serving in India, the noble, the chivalrous, the high-minded Adrian Hope.“

The censure of Robert Walpole was loudest in his own camp. The dispatch had been humiliating for the 4th Punjabis, who, having fought valiantly at Delhi and the Lucknow campaign, now stood accused of being unwilling to follow orders. Besides this, their well-respected captain, William Cafe, was severely wounded, and young Edward Willoughby, whose brother had blown up the Delhi Magazine in May 1857, was dead. The retreat had been so sudden the Punjabis had been unable to collect all their dead and wounded from the field, which was strongly against their principles. To make matters worse, the next morning, just before the Punjabis returned to Ruiya, one of the men, who had been left for dead, crawled into camp and told them a ghastly story. As soon as Walpole had vanished, Singh’s men had poured out of the fort, carrying lanterns, intent on plundering the dead and killing anyone who was still alive. He had tried to play dead, but “when a man was trying to turn him over, he suddenly grappled him, wrenched the sword from him and killed him. Then, with much difficulty, for he was wounded in the thigh, managed to get out of the ditch and crawled painfully after the Regiment. The story had the worst effect on the men for it was a maxim of Wilde’s never to leave a wounded man to be cut up by the enemy, even at the sacrifice of many lives.” When they returned, they found the dead had been horribly and insultingly mutilated. They had also lost their favourite and highly respected Indian officer, Subedar Major Hira Singh. While the Europeans buried their dead, the Sikhs cremated his remains with every military and religious honour they could. Like Hope, Singh had been shot through the neck by a man sitting in a tree.

The 4th Punjabis lost all of their most senior officers in the affair at Ruiya and would continue their march commanded by Lieutenant Stewart with Lieutenant Stafford and Hawkins under him – the latter had but recently joined. It seemed to Surgeon Fairweather, who had seen his Regiment suffer so much for so little gain, that their once proud spirit was broken. The men confided in Fairweather that they felt they were being expended for no good reason, and they would never see their homes in the Punjab again. They had marched to the siege of Delhi in 1857 with twelve officers and eight hundred men, and now there were only 109 of the original contingent left.

In the ranks of the 42nd and the 93rd, dislike of Walpole boiled over into pure hatred. For these same regiments that had climbed the Alma together (and the 93rd that formed Campbell’s Thin Red Line) had been ordered to retire, a humiliation they were hardly likely to forgive Walpole for. At the funeral on the 16th, the atmosphere was so bad that the officers were worried they would have a mutiny on their hands. To make matters worse, when the 93rd’s sentries reported that Nirpat Singh was leaving the fort, and indeed had passed only a few hundred yards in front of them, General Walpole ignored their reports, and they were told to desist from disturbing the camp any further. An enraged Lieutenant Gordon-Alexander had to be prevented by clearer heads than his from ordering his picket of 60 men, two guns and a few Sikh horsemen to march straight back to Ruiya and take the fort that very night themselves. Out of sheer insolence, the saying “Tull ye tak’ Ruiya” for any order that was issued in haste was prevalent in camp, and the men took to calling the fort “Walpole’s Castle”. Wisely, Walpole avoided direct confrontation with the rank and file as much as possible. Surgeon Fairweather believed the Highlanders would have liked nothing better than to shoot Walpole dead, and rightly surmised Hope and the others had been done to death by the “mismanagement of an arrogant nincompoop.” At Hope’s funeral, the officers had even expected the troops to rise in mutiny.

The problem was, they would have to fight for him again.

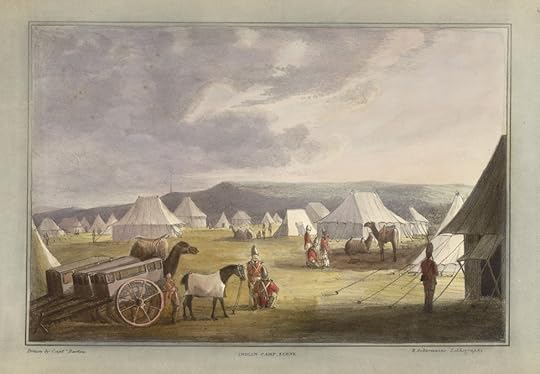

Sirsa, 22 April 1858The force marched on 18 April, and much to the immense irritation of the surgeons, it looked like camping on open plains was once again on the menu. After a few more men collapsed from the heat, Munro ignored Walpole’s directive and ordered the 93rd to set up their tents in a grove of trees; they were quickly followed by the other regiments. Walpole decided this was not the time to object, and he let this piece of obvious insubordination pass by without a word. At this point, no one really cared if he boiled his head.

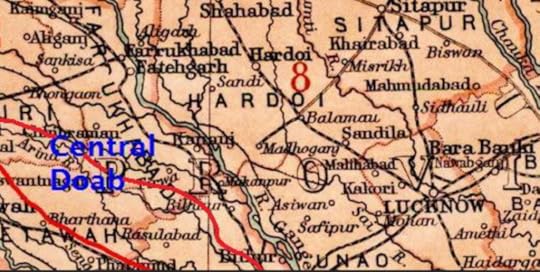

After five marches, on 22 April, they reached a strong village on the right side of the Ramganga, named Sirsa, only seven miles from Aliganj. The cavalry of the advanced guard reported back that they had made contact with a rebel picket that was in the process of retreating. Walpole was loath at this point to make any attack on the rebels retreating or otherwise, but after some persuasion for Haggart and Brind convinced him that an attack could be carried out with little loss, provided they were allowed to manage it.

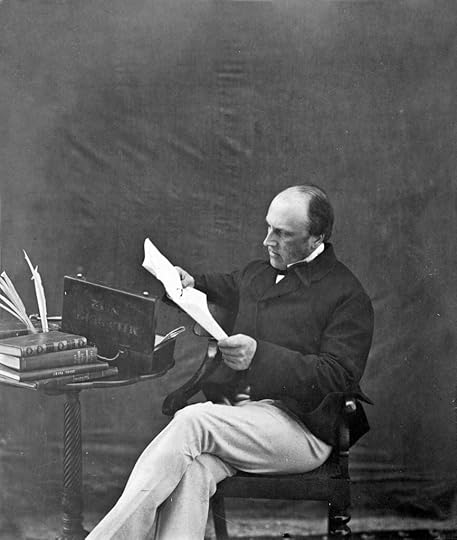

Major General Sir Henry Tombs VC KCB

Major General Sir Henry Tombs VC KCB

“The column was halted, in order that the heavy gun might be brought to the front and the infantry close up. The horse artillery and the cavalry, however, went ahead. When about a thousand yards from the largest village, the enemy opened fire with their six guns and sent their shot and shell among them. On they galloped together, for it was Tombs’ proud boast that his light guns could go wherever the cavalry could go. Six hundred yards from the village, they drew rein. The 6 – pounders quickly came into action, and the rebel fire slackened. The troop of 9 -pounders, retarded by the broken and difficult ground, came up, and soon silenced the united tearing fire of the enemy’s guns, and drove their infantry from the village and the shelter of the trees. Their cavalry showed a bold front, in the hope of saving their guns, which were being slowly dragged away by bullocks, but a flank movement and the advance of the infantry disconcerted them, and they fled. The pursuit was conducted with such vigour by the cavalry and artillery that the enemy’s camp was captured.“

This time, Walpole was prudent with the use of his infantry, whom he kept well in reserve, ensuring this time, they did not fight at all. While Sirsa was seen as a small victory, the men in his camp were cognisant of the fact that Walpole did not carry it through, and most of the rebels escaped to join their compatriots at Bareilly.

“The infantry was formed up accordingly, with the 79th Highlanders leading in line, supported by the 4th Panjabis , the 42nd and 93rd Highlanders following in line of contiguous columns in reserve. Walpole’s bad generalship showed itself again by allowing the infantry brigade to be hurried across the ploughed fields for nearly four miles at a run, in a foolish endeavour to keep up with the cavalry, under that awful sun…It was reported in camp that evening that it was only on the urgent representations of Brigadier Haggart, 9th Lancers, commanding the cavalry, that our pig- headed General allowed him to follow the retreating foe up, with the result that the Horse Artillery and cavalry captured the village before we of the infantry could overtake them.”

The only satisfaction that the infantry had after this was when the cavalry reported that many of the men they had cut up had belonged to Nirpat Singh, so in a sense, it was a vengeful victory after all. The remainder of the rebel force left their baggage behind, and the cavalry captured four guns. They retreated on this occasion in such a hurry that they neglected to destroy the bridge over the river, and Walpole could now move his guns and column closer to Aliganj without worry. The same day as he took Sirsa, the force continued its march towards Aliganj and encamped one mile outside the town. Here they remained until 27 April, when they were joined by Sir Colin Campbell.

Colonel Walpole is not censured

Colonel Walpole is not censuredIf the Highland Regiments expected Sir Colin Campbell to tar and feather Walpole, in this instance, his famous temper let them down. Instead, he let Walpole off, and much of this had to do with Walpole’s dispatch. He had stated officially that the infantry “had gone much nearer to the fort than I wished or intended them to go,” and Sir Colin Campbell concurred that his difficulty was not so much down to poor leadership and bad management but the temper of the Highlanders.

“The difficulty with these troops … is to keep them back; that’s the danger with them. They will get too far forward.” Sir Colin would later allude to the Ruiya affair and to the“rashness of officers in a subordinate position attempting to blame or judge the act of their superiors, of the strength of those mud forts, and of the difficulty of restraining their Highlanders.” He did not take into account either the reports of Brind or Haggart, and above all, he disregarded the Highlanders themselves.

“As was Sir Colin’s wont, especially since he had been gazetted to the Colonelcy of the 93rd Highlanders, he visited our lines in the evening, commencing with a stroll amongst the men’s tents, addressing men he knew by name, and asking how they were; but he received short and rather surly answers, such as, ‘Nane the better for being awa frae you, Sir Colin; or, ‘As weel as maun be wi’ a chiel like Walpole,’ till, the news spreading that Sir Colin was among the tents, all the men turned out and fairly shouted at him, ‘Hoo about Walpole?’ – meaning, what was he going to do with Walpole after that terrible Ruiya business. Sir Colin was evidently much disconcerted (for the commotion in camp brought me to my tent – door, and I myself saw and heard what I have above described), and, instead of going on to the mess tent, went straight back to his own camp, and until after the battle of Bareli not only did not come near our lines again, but took no notice of the regiment when riding past us with his staff on the line of march .” (Alexander)

This certainly matches what William Russell had to say about Walpole, when writing on the 27th – “His manners are unpleasant, and he has managed to make himself unpopular. It would be impossible to give an idea of the violent way in which some officers spoke of him today.” Even Russell expected Walpole would at least receive a dressing down, but nothing of the sort happened. Sir Colin Campbell interceded on Walpole’s behalf, not only with the officers under his command but with Lord Canning, who was fretting about what to do with the man and lamenting the loss of Adrian Hope. His words must have been soothing, for Walpole was recommended for, and received a C.B. and later a K.C.B., and from Sir Colin Campbell, the command of the Bareilly division. It was seemingly enough that Sir Colin Campbell trusted and believed in Walpole as a leader for those who had authority, to overlook the senseless slaughter at Ruiya. That Sir Colin Campbell could not look his favoured 93rd in the eye, however, tells another story in itself.

As Malleson writes:

“It is a curious commentary on the principle then, now in fashion, of conferring honours on men, for the deeds they achieve, but for the high positions they occupy, that the general who lost more than one hundred men and Adrian Hope, in failing to take this petty fort, was made a KCB. Though he failed to take the fort, he was yet a divisional commander.”

Malleson was alluding here to Walpole’s influential background – his mother was the youngest daughter of the 2nd Earl of Egmont and sister of Prime Minister Spencer Perceval – the only British prime minister ever to be assassinated. His grandfather was Thomas Walpole, who himself was the son of an eminent diplomat, Horatio Walpole, 1st Baron Walpole, who happened to be the younger brother of Robert Walpole, the first Prime Minister of Great Britain. It is no wonder that no one was willing to give this Robert Walpole a rebuke, not even Sir Colin Campbell.

Following Bareilly, Walpole was left in command of the Rohilkhand division until 1860. Before the mutiny was completely extinguished, he would have one more fight, on the Sarda River, where he did shine through as a leader of a small force in a skirmish. For his mutiny services, Walpole received the Mutiny Medal with one clasp for Lucknow; by the home authorities, he was first made Companion and then Knight Companion of the Order of the Bath (military division) and received thanks from Parliament. In 1861, he took command of the Lucknow Division, but it was a short posting, for in the same year, Walpole was transferred to Gibraltar to command the infantry division. Promoted to major general in 1862, he returned to England two years later to command the Chatham Military District, a position he stepped down from in 1866, upon being given a colonelcy of HM’s 65th Regiment of Foot. Promoted to Lieutenant-General in 1871, Sir Robert Walpole died on 12 July 1876 at the Grove, West Molesey, Surrey.