Essays on Art

Though I have never been to art school, I’ve been able to read a lot about cultural theory in the work I’ve done. In my first year of university, I took a second year theory and practical criticism course for English Lit. To my surprise, there was very little reading in the course – just this one binder that was full of watered-down theory and snippets of poems that applied in order to illustrate the concept of the week. If we were going to do Derrida, we got a few bullet points on deconstruction, and then a poem by Plath where we had to find how all the Binary Oppositions worked within the text and “deconstruct” it ourselves. Very basic introduction to the mess that can be any type of abstracted theory. It was very useful at the time.

But what I loved even more about this course was that for most of the lectures, we got art to analyze instead of books or poems. Since so much of art history lines up with literary history, they are interesting mirrors of one another. At the same time that Christina Rossetti is writing “Goblin Market,” her brother is heading the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and painting gorgeous masterpieces. It would be ridiculous to look at one of these pieces in isolation – they have to be viewed together in order to understand the motivations for painting and the aesthetics at the time. Another thing that tends to be overlooked is that we “read” a painting just as much as we “read” a text. We view it and find symbols and images, equate meaning with those, and then come to a conclusion about what we’re looking at. We are always “reading” in our everyday lives – and this is why everything can be a text. If you can look at something and form an interpretation about it, you are creating a text.

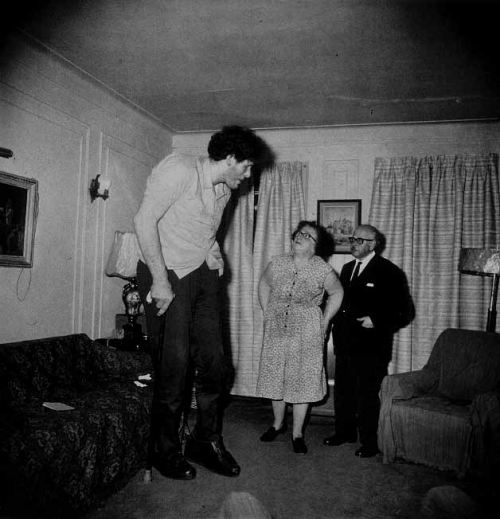

All theory consists of is different ways of reading the world and those texts around you. So of course, in this English Practical Theory and Criticism class, we were given art. It was the instant text. They could throw up an image by Georgia O’Keeffe and ask us what we thought we were looking at. They did this for fun, too, knowing that most of us would say that O’Keeffe was painting vulvas in her flower pictures, but also knowing that a few people would resist that reading (“a flower on fire,” instead). Once that resistance to one form of interpretation has happened, we then begin to see that our own way of seeing is completely subjective. One person may read a photo by Diane Arbus as pure exploitation, and another may read it as liberation. Both of these people are using the same content for their conclusion about their work (because she took pictures of “freaks”), but the way that their thoughts are constructed, their ideological place in relation to that photo – that is what is different. As soon as something is different, we begin to name it and categorize it. Lo and behold, we have different branches of theory. Different branches of thought. There is nothing inherent in the photographs that Diane Arbus has taken. Both readings – exploitation and liberation – are right and wrong because of this. Theory is always right and wrong — it is never a final answer, only a way of thinking about the world and the texts that you are given.

So I digress a little bit. While this course was my first brush with the ‘heady’ academic works that I would get into later, it was also a huge influence for TDK. We used a lot of photography in that class, making me want to make Thomas a photographer more and more, especially since the artistic intention of the artist is removed. It is not his eternal creation and true authentic feelings he is creating when he takes a photo – or when any photographer may do that. They are just there are the right place and the right time, and then perhaps impose a meaning on it. Meaning and context are what titles give to texts. But all of this is outside the art piece itself, and influenced by the author/artist as much as it is through the audience. Roland Barthes, an excellent theorist that I managed to come across much later, provides some great insight on the relation of the author/artist to their work and their audience. His books The Pleasures of The Text, S/Z, and Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography express these ideas quite well, but all his books are good. He is one of the key thinkers when it comes to a “deconstructed” worldview where the idea of looking at art for essential meaning just does not work anymore. It’s not about the answer anymore, it’s how we reach that answer.

I think this is a huge distinction and something that needs more attention. We can sit around for hours and discuss how much we love and hate something, but it ultimately leads us nowhere. I put this Le Tigre song “Slideshow at a Free University” in this post because I think it picks up on this distinction and is able to articulate it in a fairly interesting manner. “It is our function as artists to make the spectator to see the world our way, not his way.” That is exactly it. And while I enjoy Barthes and Foucault for what they have done to the author function in literature, I want to talk about what I think are some of the most important texts in understanding the ways in which we look at and understand art.

A lot of the time, either Vivian or Bernard, since they have gone to art school and would have studied these theories (even more so since the timeline of their education matches up well with when these authors were in their heyday), will parrot some of these thoughts. A lot of academic articles and writing can be just too much to read right away. I also find that sometimes academic articles miss the point entirely; they can easily overwhelm their work with jargon that only a handful of people will really understand. Their audience shrinks immediately and the people that they end up talking to already know what they are saying. It becomes a sense of “preaching to the converted.” By also making it far too abstract, you lose a lot of people by not giving tangible examples. You need theory AND text which to use. This is why I always appreciated how in that class, the power point they had always had an image to go along with it. This is why I attempted to write fiction and make those theories work through the people that can embody one view point or another. Vivian can be Barthes, and Bernard can be Adorno and they can banter back and forth for awhile. It can have a context and become a thin allegory for a few paragraphs, and then get back to the narrative. (Sexuality and gender studies, too, I think, also miss this point within academia; talking about sexuality is an intensely private thing and something that evades language most of the time. You can practically become mute when you try to speak about it in an abstract sense in an academic way. But by portraying relationships between people, thought process that happen when people are together, you can better articulate points by not writing an essay. I think, at least, and again, I hope I’ve managed to do.) But anyway, onto the essays!

These three essays changed my way of thinking about art and the culture’s relation to it, but this is by no means an exhaustive list. Ideally, I encourage everyone to go out and seek more information about theory, but I understand that it’s not fully possible for many people either. But for what it’s worth, enjoy!

1. Walter Benjamin (pron. Ben-yamin). “The Work of Art in the Mechanical Age of Reproduction.”

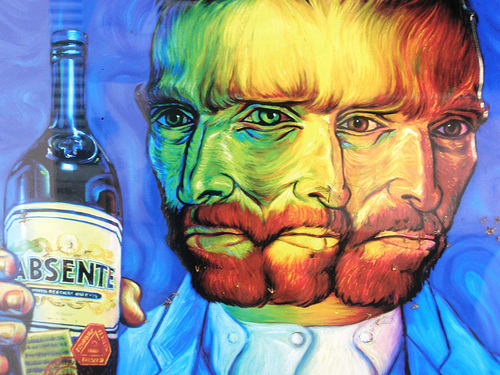

What happens when the production of art becomes an industry? Does Van Gogh lose his validity and the work’s enchantment if it is reproduced everywhere? These are the types of questions that Benjamin attempts to answer. His concept of “aura” and the ways in which we view original pieces of work are taken up in this essay. He was ahead of his time for speculating on the changes that would happen when the form of art began to change and the modern cities as we know them began to be produced. A lot of his writing is eerily applicable to now, nearly a hundred years later, because of the digital culture surge and the changing mediums for most cultural products. His writing on The Storyteller is another piece by him that I would highly recommend, too.

2. Pierre Bordieu. “The Field of Cultural Production.”

I read this again recently and it was an interesting experience to see how much my thoughts have changed due in part to this essay and his other work. His notion of habitus is impressive, but the ways in which high culture and low culture meet on the “field” as he describes it is integral. We all know this instinctively, living in the culture and just observing. What constitutes the field itself now needs to be updated, but the content can easily be swapped out and exchanged. The structure of thought is what is important. Theodore Adorno also has done good work on this meeting of high and low culture, and his book on aesthetics has been highly influential, too.

Since it’s a dense article, here is a youtube summary. :)

3. Jean Baudrillard. “Simulacra and Simulation.”

This is a bit longer than the other pieces, but it is worth the read. While a lot of what Benjamin has written can be applied to our current society, Baudrillard’s text and his other work is far more apt to describe the ways in which digital culture, interactive texts, and video games have merged into our consciousness. He outlines ways in which we can view our own thought patterns and the ways in which we form identity in a culture now that is producing texts that are either too real (hyperreal) or too fragmented. What is real and how does this exactly change us? For anyone who has even gone a little bit into Sci-Fi literature, you see the influence of his theories. The ways in which art has changed in form over the last few decades are very important to think about in relation to his work. We no longer have static pieces anymore (though one could argue that they were never static to begin with) and we no longer have static thoughts.

I can really see these theorist’s influence, whether or not it is intentional, on the new MCR album Danger Days. It is a dystopian future where a lot of reality is mimicked and there are constant questions about identity in relation to the media. That album is full of even more post-modern and theoretical references (then again, I could be reading into it too much). Michael Warner’s book Publics and Counterpublics represents the dynamic between the Draculoids and the Killjoys quite well; Donna Harawy’s cyborg manifesto is a more positive spin on the future of identity and hybridity; Raymond Williams has also described the ways in which we think about things (ideological perspectives), only he has tackled it a little differently. In Marxism and Literature, he has described “structures of feeling” which encapsulates how certain time periods and epochs represent themselves through affect. Why is it that so many people seem to be expressing their anxiety about their identity in different ways? He asks, then looks at the culture and explores feelings. Since these influence our thinking, no matter how rational or logical we like to think we are, he is another important text to look at.

And then, also, as always, in order for most of this to make sense, we cannot forget about Karl Marx and his communist manifesto. Bernard specifically mention Marx in a few sections and a lot of Jasmine’s ideas are influenced by the thinker as well. Marx and Engels have looked at the origin of the family and how it has all been based around an economic principle. Shulamith Firestone has tackled Marx (and Freud, who I will get to later) and used his way of thinking about the capitalist system to launch her own critique on the family and criticize love. By perpetuating these myths and having stories that illustrate the “happily ever after” people literally buy into love and family relationships, thus perpetuating the capitalistic system that makes them unhappy in the first place. While I don’t take quite as cynical view as this in the story, it is a valid criticism and observation. All of this is from her book The Dialectic of Sex and would also not be possible without the influence of Freud on early thoughts of sexuality.

Most critical texts within the last hundred years would not have been possible without Sigmund Freud or Karl Marx. Even if you disagree with them and their ways of thinking, you are still basing your own thinking off them. All negation relates to something prior. I don’t like everything Freud says, but man, did he influence a ton of people after the fact, some of whom I do agree with. So, in addition to the communist manifesto, Freud’s Three Essays on Sexuality needs to be considered, too.

That seems like enough links for one day, yes? I have probably just outlined an entire syllabus here, so I will be on my way. :)

Evelyn Deshane's Blog

- Evelyn Deshane's profile

- 46 followers