Pamelia Chia's Blog

November 9, 2025

Postcards from Croatia

The seafood section of the Zadar Market

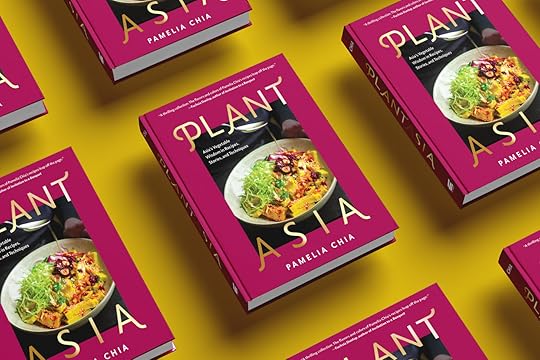

The seafood section of the Zadar MarketIt’s been a while! Lots have been happening over here. For one, the new edition of PlantAsia is now out in the world! It was first self-published in 2023, so it is thrilling to work together with The Experiment, a New York publisher, on an edition with new recipes and a glossary for those who are unfamiliar with Asian ingredients!

We were also recently in Croatia with my in-laws who flew over from Singapore. Prior to our trip, I had no idea that Croatia produces some of the worl'd’s best olive oils. The Istrian region, in particular, has a long tradition dating all the way back to the Roman era. I was like a kid in a candy store at Stella Croatica, a family-run estate that encompasses a botanical garden, an olive museum, a manufacturing area where sweets and olive oil are produced, and a shop. I also enjoyed the Istrian Olive Oil Museum, which was considerably smaller but offered private tasting sessions on identifying quality olive oil (my notes here). Right next to the museum was the Roman Arena, which sits atop an underground museum dedicated to olive oil production in Istria.

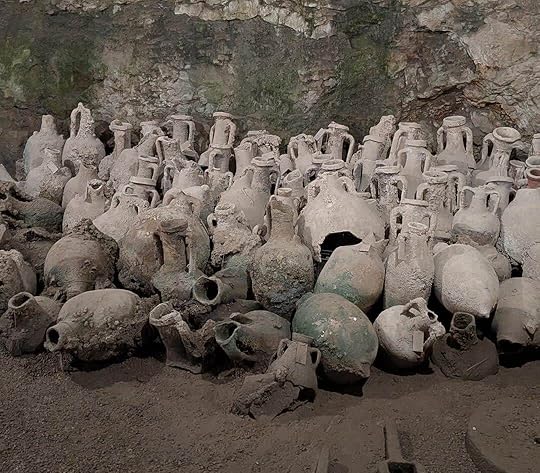

The traditional vats used to store and transport olive oil in Istria.

The traditional vats used to store and transport olive oil in Istria.Naturally, I had to leave Croatia with a few bottles of olive oil. It’s easy to find great ones with the many specialty stores (I love Aura Distillery Shop) — but the freshest, and most affordable, olive oil I purchased came from Lavender Deklevi. Their olive oil was only 10 days old when I made the purchase! There were many olive oil farms and cooperatives in the area, and I only wish we had more time and luggage space.

My bottle of olive oil from Lavender Deklevi.

My bottle of olive oil from Lavender Deklevi.Apart from olive oil, Croatia’s Istrian region is also known for its truffles. There’s the charming town of Motovun, whose surrounding forests are some of the richest habitats in the world for truffles, and there’s even a truffle museum nearby. Truffle Museum by Karlic may be small compared to the olive oil museums, but the family that runs it was so warm and generous in allowing us to taste their products that it made the drive worth it!

When we were in the Istrian region, we realised that Slovenia and Trieste were close by, so we visited them both in one day, starting with the Sečovlje/Sicciole Saltpans Nature Park in Slovenia. The saltpans have been operating since the 13th century and were a major source of wealth for the region. We spent the evening in Trieste (Italy) and Gelateria Zampolli made such an impression with its true-to-flavour gelatos. I particularly loved their persimmon, as well as chocolate + ginger + chilli gelato.

Our best meal in Croatia was undoubtedly at Padela, a pasta specialist. Every dish was executed flawlessly — with each house-made pasta designed to match a specific sauce or preparation. It was the kind of meal that I wish I could experience again and again. Back in the Netherlands, I kept thinking about their incredible pistachio and anchovy pasta, made not with a pistachio pesto, but rather a sort of savoury pistachio cream that gets its oomph from anchovies.

Inspired, I made a pistachio & chicken caesar salad over the weekend and it was such a hit with us that I thought I’d share it with you! The convenient thing about a chicken caesar is that it’s a full meal on its own, the salad equivalent of a one-pot dish. This one is reminiscent of the famous roast chicken salad by Zuni Cafe, where the croutons are tossed with the chicken roasting juices, though if you want to make this salad a meatless one you can — the combination of pistachio and anchovy is definitely memorable enough.

Pistachio & chicken caesar salad

Feeds 2 hungry people or 4 as a starter

October 16, 2025

a weeknight dinner idea

It’s officially fall in the Netherlands and life for me has entered a hectic phase. For one, I’ve started going to Dutch language school twice a week. Taalcafe—the Dutch practice sessions at the library organised by volunteers—is back in full swing from summer break. Classes at the cooking studio are ramping up as the days get colder and everyone wants to spend time indoors. I’ve started working once a week at a fantastic little Mexican restaurant that recently opened up near my apartment. M cookbook PlantAsia: Asia’s Vegetable Wisdom in Recipes, Stories and Techniques is launching soon, and meanwhile I’m trying to polish up the manuscript for my next cookbook.

It’s wild, but also a wonderful rhythm that I feel grateful for. I’m relishing feeling like a student again—both in the kitchen and in school—while drawing fulfilment also from my teaching job. It feels like special to be able to express and satisfy different parts of myself through the various roles I now hold, and I count my blessings constantly.

All this to say, cooking dinner daily can sometimes be tricky as I shuttle from place to place. But, as always, I look forward to enjoying a home-cooked dinner and believe it to be one of life’s luxuries. This weeknight meal is one of my favourites, in how it comes together in 30 minutes (or the time it takes to cook rice), while being endlessly comforting and customisable to what I’ve got in the refrigerator.

The inspiration comes from my time at the Mexican restaurant. I believe Mexican cuisine to be one of the most underrated cuisines on the global stage, and at the same time feel a kinship with the cuisine as there are so many parallels to the kind of ingredients and flavour profiles we enjoy in Singapore: coriander! Raw onions! Dried chillies! Banana leaves! At the restaurant, I’m learning to use a traditional clay comal (traditionally used to heat tortillas, toast spices, or roast chillies) and work with new ingredients such as nopales and dried jalapenos… but above all, I frequently marvel at how Mexican cuisine is able to wring so much flavour out of the simplest ingredients.

One of the eye-openingly delicious things I’ve learnt is what I call Lisa’s rice. Lisa is the co-owner and chef of the restaurant and her rice draws upon the traditional Mexican way of cooking rice—toasting the rice in oil and onions before adding water. She flavours the rice with lime leaves, and the end result is so rich, fragrant, and comforting, I could have sworn it was made with coconut milk or chicken stock. I’ve since adapted it for weekday nights and have prepared it several times now, and it’s always invited a lot of praise and appreciation. Lime leaf is still my favourite, but on occasion I cook the rice with lemongrass and pandan.

A very fitting main course to serve with it is sambal fish. Growing up, my mother used to slather whole fish in jarred sambal, wrap it in a banana leaf, then grill it in our oven until the char of the banana leaf and the sizzling sambal took over our kitchen. Hawkers make a variant with stingray, grilled more expediently on a flat-top or sizzling cast-iron plate. At home, it’s really not difficult to replicate this. A simple pan and your favourite store-bought sambal can be used (I use my homemade rempah, turning it into a sambal with belacan, sugar, and tamarind).

For a vegetable side, I like something fresh, refreshing, and slightly tart. I have a love for Sri Lankan-style sambols massaged with freshly grated coconut, lime juice, chillies, and onion. Almost any greens you like can be used; the traditional choice is gotu kola (pennyworth) but I reach for kale since I’m in the Netherlands. The defining ingredient is grated coconut, which adds a lovely richness and milky sweetness, which balances the lime juice well.

These two dishes are so quick to rustle up that you can prepare them as the rice cook. By the time the rice is done cooking, you’ll have a full meal. Recipes for the entire meal below.

Lisa’s rice (adapted)

Makes 4 servings

August 31, 2025

A guide to making fried shallots

Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every week, you’ll receive historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks, Wet Market to Table and PlantAsia, are available for purchase here and here respectively.

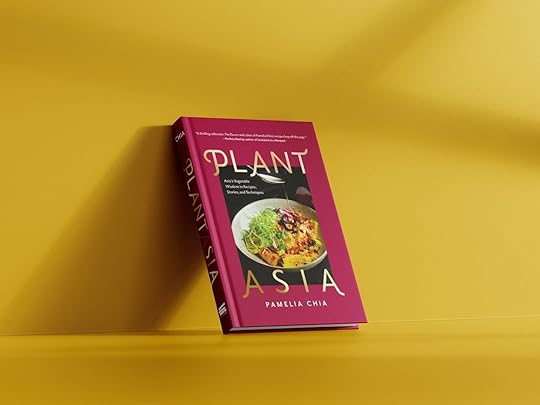

The new edition of PlantAsia, hitting shelves in October 2025.

The new edition of PlantAsia, hitting shelves in October 2025.HOMEMADE FRIED SHALLOTS

Fried shallots are a common pantry staples in Asia, and if you’ve never had homemade ones, you’re missing out. Think of them as having the intense, sweet-savoury flavour of caramelised onions, but with a delicate crunch. Although most Asian supermarkets stock fried shallots affordably, making your own yields a far superior flavour—and a bonus: infused shallot oil. Frying shallots can be tricky, but here are some principles I follow:

Use a mandoline to slice your shallots: In Asia, small purple shallots are traditional, but if you only have access to Western shallots, which are longer and tapered, that’s no issue (in fact, that’s what I use here in the Netherlands). A knife will do the job, but a mandoline makes quick work of it and gives you thinner, more consistent slices that fry evenly. I use a Japanese mandoline, but small, palm-sized mandolines are inexpensive and easy enough to find.

![slicing.mp4 [video-to-gif output image]](https://images.gr-assets.com/hostedimages/1756829083ra/37192380.gif)

Use room temperature oil: When you deep-fry something at high temperature, it crisps and browns the exterior while keeping the interior moist—this moisture is the enemy of crispy fried shallots. Starting with cold oil allows the moisture in the shallots to cook out before they begin to brown and crisp, avoiding a soggy end-product.

Use a good amount of oil: The oil-to-shallot ratio is a big factor in whether the fried shallots turn out crisp or mushy. Sufficient oil ensures that all the shallots can float and freely circulate for even cooking, and avoids overcrowding which can result in the shallots softening and steaming instead of crisping.

![oil.mp4 [video-to-gif output image]](https://images.gr-assets.com/hostedimages/1756829083ra/37192381.gif)

Cook on low heat: When the oil and shallots are first heated, there’s a lot of bubbling as moisture escapes from the shallots. I cook the shallots on low heat so that this moisture has enough time to cook out before the shallots brown.

![bubbling.mp4 [video-to-gif output image]](https://images.gr-assets.com/hostedimages/1756829083ra/37192382.gif)

Pull them out early: As the moisture inside the shallots evaporates and the oil reaches frying temperature, the shallots begin to fry and the sugars caramelise. Don’t let the shallots get to a deep golden brown because the shallots will continue to brown from the residual heat—pull them from the oil a little before they look right to you (light golden brown is ideal). Always have your paper towel-lined sheet tray and spider ready well in advance because the difference between perfect and burnt is seconds.

![WhatsApp Video 2025-08-31 at 19.19.20.mp4 [video-to-gif output image]](https://images.gr-assets.com/hostedimages/1756829083ra/37192383.gif)

Cooling and storing: The crispness of the fried shallots isn’t coming from flour or starches being fried but from caramelised sugars. When you first pull them from the oil, the shallots will feel somewhat limp—this is to be expected as the sugars are molten. However, as the shallots cool to room temperature, these sugars harden and the structure stabilises, producing that brittle, crunchy texture. Spread the fried shallots in a thin layer immediately after frying. Use your hands or chopsticks to separate any clumps to help any trapped steam to escape. Once cool, you can transfer the fried shallots to an airtight container or jar. Silica packets can extend shelf life, especially in humid climates. Otherwise, a quick flash in a hot oven before use can refresh them.

![WhatsApp Video 2025-08-31 at 22.53.20.mp4 [video-to-gif output image]](https://images.gr-assets.com/hostedimages/1756829083ra/37192384.gif)

Two internet hacks, tested

Left: shallots that were salted before frying; Right: shallots that were tossed in cornstarch before frying.

Left: shallots that were salted before frying; Right: shallots that were tossed in cornstarch before frying.- Salted fried shallots (left in photo): While fried shallots are traditionally not salted, some cooks salt their shallots before frying to draw out moisture. In theory, this should help the shallots dry faster and crisp more evenly in the oil. However, there are real downsides to this method. The main one is that it is hard to control saltiness; too little salt does nothing, too much makes the finished shallots unpleasantly salty. Depending on how evenly the salt was distributed, the frying of the shallots could also end up uneven. The other thing I noticed was how dull and matte the salted fried shallots looked. When you salt shallots, the sugar-rich juice gets pulled out of the cells, leading to less sweetness and caramelisation in the finished fried shallots.

- Cornstarch-tossed fried shallots (right in photo): Tossing shallots in cornstarch before frying is another “hack” I read about. The starch coating helps to absorb moisture, and gave the shallots a crunchier, potato chip-like texture. The shallots also had a more “separate” texture—you almost feel each individual ring of shallot. Apart from enhancing crisp, the starch coating also doubles up as a thin protective barrier around the fried shallots, reducing the shallots’ exposure to humidity, thus extending shelf life. In fact, commercial fried shallots are often lightly coated with starch or flour before frying. However, the problem with using cornstarch is that the starch coating interferes with sugar caramelisation. This means that you get more matte-looking shallots, compared to the glossy, golden ones fried without starch. Since the caramelisation is limited, the flavour leans towards a neutral, muted flavour rather than a deeper, sweet-savoury note of pure fried shallots.

Using fried shallots and shallot oil

![WhatsApp Video 2025-08-31 at 23.01.56.mp4 [video-to-gif output image]](https://images.gr-assets.com/hostedimages/1756829083ra/37192386.gif)

Fried shallots are perfect as a garnish or flavourful, crunchy element in porridge, noodle soups, cold noodle dishes, salads, sandwiches, biryani—really, anything you can think of would be improved by it. The oil left over after frying is intensely flavoured and has as many uses for it as garlic butter. Fry eggs in it, make fried rice, drizzle over noodles, or make a salad dressing with it. It is also excellent as a base for chilli oil or mayonnaise.

Fried shallots

Makes 1 jam jar’s worth | Vegan

August 24, 2025

Mango pudding

Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every week, you’ll receive historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks, Wet Market to Table and Plantasia, are available for purchase here and here respectively.

Today’s deep dive into mango pudding is inspired by a message I received from one of our paid subscribers, Polly, who says, “Mangoes are indeed plentiful now here in sunny Southern California. Would you know a good Hong Kong yum cha style mango pudding recipe? I recently scoured the internet and found a very promising recipe developed by a HK chef but it turned out really hard. I was going to redo the recipe by tweaking the liquid & gelatin powder ratio; but thought I would check in with you first for your advice. I like that that chef included coconut milk & ice cream in his recipe. A drizzle of evaporated milk at the end always adds a touch of nostalgia.”

If you’re a paid subscriber and have a topic you'd like me to explore, I’d love to hear from you. Thank you for being here, and enjoy this week’s post! ✨ — Pamelia

PLANTASIA UNBOXING

pameliachia A post shared by @pameliachia

A post shared by @pameliachiaRecently, my author copies of PlantAsia arrived on my doorstep, and I was thrilled to see that it was every bit as beautiful as I had imagined! Preorders make a big difference in a book’s success—when numbers are strong, bookshops and sales teams put extra energy into getting it out into the world. The book officially lands in bookstores in late October, but if you preorder now, you’ll also receive a special booklet with bonus recipes as a little token of gratitude. Thank you so much for your support—I can’t wait to share more with you and take you along on this journey!

MANGO PUDDING

When I was growing up, mango pudding was a common snack in our refrigerator. We bought it from the supermarket in a pack of six plastic cups, and it tasted more like mango jelly with a hint of dairy. The version you typically get at Hong Kong dim sum restaurants or cha chaan tengs, however, is satisfyingly custardy without being heavy, with evaporated milk or cream as a key component.

Mango pudding has roots in Western-style custards and gelatine desserts. European desserts like blancmange—a dairy-based dessert thickened with gelatin or cornstarch—were introduced to Asia through colonial trade routes in the 19th and early 20th centuries. In regions abundant with mangoes, locals adapted these custards by incorporating fresh mango pulp while retaining the smooth, gelatinous texture of Western-style puddings.

While this is a simple, do-ahead dessert to put together, there are a few tips to ensure success:

Fresh vs canned mangoes: Ripe, in-season mangoes are ideal, though canned mango pulp works great too. Some fresh mango varieties contain protein-digesting enzymes that break down gelatine chains and prevent the pudding from setting properly. Canned mango puree doesn’t have this issue because the enzymes are deactivated during pasteurisation. If using fresh mango, a gentle period of heating is enough to denature the enzymes and avoid this problem.

Gelatine sheets vs powdered gelatine: I prefer gelatine sheets over powdered gelatine. The latter must be sprinkled over cold water to bloom before dissolving in warm liquid, and if not done correctly, it can clump. Gelatine sheets are more foolproof: soak them in cold water until soft, squeeze out excess water, and dissolve in warm liquid. Avoid adding gelatine sheets to boiling liquid, as high temperatures can break down the protein chains and affect the set.

Quantity of gelatine sheets: This makes all the difference between a rubbery pudding and a soft, custardy one. Although gelatine sheet packaging often suggests a specific amount for a given volume of liquid, it’s best to treat this as a guideline for firm gels, like moulded jellies, rather than for soft puddings. Also, since mango pulp adds solids and thickness, the effective liquid content is actually less than the total weight, meaning less gelatine is needed to achieve the perfect set.

Unmoulding: You can serve mango pudding directly in the dish or unmould it. Lightly grease each cup with oil before filling. Before serving, dip the dish in hot water for a few seconds before inverting.

MANGO PUDDING

Makes 4 servings

August 14, 2025

Nasi lemak kukus

Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. It’s great to have you here!

Last Saturday, we were invited to our friends’ home for a potluck to celebrate Singapore’s 60th birthday. Wex and I brought coconut rice and otah enough to feed ten and enjoyed a feast:

Even though knowing how to cook rice is one of the most fundamental things about being Asian, it still makes me nervous whenever I cook it for a gathering—because with rice, it’s all about getting ratios right. Throw coconut milk into the mix, and it’s even harder to nail; too little and you end up with coconut rice (nasi lemak) that’s lacking in richness and fragrance; too much and the rice struggles to cook through and turns clumpy and mushy. A quick glance at Reddit threads on coconut rice troubleshooting reveals just how frustratingly riddled this seemingly simple dish is with pitfalls.

I’ve previously done a deep dive into making coconut rice in a rice cooker, but this time, I want to sing the praises of a more traditional approach: nasi lemak kukus. Unlike the rice cooker method, the kukus method involves a steamer and a bit more patience but the payoff is worth it. When cooking for a crowd, it’s a dream—easy to scale up or down, with guaranteed fluffy, perfectly separated grains every time. I’m convinced that once you try making coconut rice this way, you’ll fall for it as hard as I have.

Enjoy,

Pamelia

PREORDER PLANTASIA

The new edition of my cookbook PlantAsia is available for preorder now. Click on the image above for preorder information and links!

The new edition of my cookbook PlantAsia is available for preorder now. Click on the image above for preorder information and links!THE TROUBLE WITH RICE COOKERS & THE ALL-IN-ONE METHOD

A typical rice cooker nasi lemak recipe might tell you to combine everything—rice, water, coconut milk, aromatics, and salt—in a rice cooker, press a button, and walk away. Sounds simple, but there’s a catch: coconut milk slows water absorption in rice.

Normally, when you cook rice, water molecules penetrate the starch granules and heat makes them swell, creating that fluffy, tender texture. But coconut milk—an emulsion of tiny droplets of coconut oil suspended in water, along with proteins and sugars—introduces fat into the mix. These fat droplets coat the surface of the rice grains, creating a thin, waterproof-like layer that slows down how quickly water can penetrate the rice during cooking, resulting in semi-cooked or unevenly cooked rice.

If, like me, you own basic, single-button rice cooker, you might also have noticed another common issue: the rice cooker “Cook” button flicks to “Warm” even though there’s still liquid in the pot. The fat in the coconut milk is the culprit here too. Basic rice cookers work with a heating plate and a temperature sensor that comes into direct content with the bottom of the pot. As long as water is present, the temperature stays at or below 100°C (the boiling point of water). Once the water is gone, the temperature rises above 100°C, signalling to the rice cooker that the liquid has been completely absorbed by the rice, and triggering the switch to “Warm.” But when coconut milk is in the mix, fat can coat the bottom of the pot, causing the sensor to heat beyond 100°C even though there’s still liquid in the pot. The rice cooker thinks the rice is done—and prematurely ends the cook cycle.

Finally, there’s the issue of temperature control. Basic rice cookers heat liquid vigorously, which isn’t a problem when rice is cooked with plain water. But with coconut milk, aggressive boiling can break the delicate fat-water-protein emulsion and cause the coconut milk to split, leaving you with a layer of curdled solids on top of the finished rice.

There’s a workaround. In my deep dive on rice cooker coconut rice, I first cook the rice with water, aromatics, and salt first, then stir in coconut cream only after the rice is fully cooked. This ensures the grains cook through completely and prevents the coconut milk from splitting. However, this method is not without its flaws: the rice tends to be slightly stickier or denser, and the coconut flavour is less deeply infused, as the grains absorb it only after cooking. For everyday meals at home, it’s a quick, fuss-free method. However, when cooking for a crowd, or chasing extraordinary coconut rice, there’s a better way.

NASI LEMAK KUKUS

Before rice cookers became commonplace, nasi lemak was traditionally made not with the absorption method, but through a two-stage steaming process:

First steam: The rice is first soaked, then steamed until partially cooked—still firm in the centre, but turning opaque. This initial steam gives the rice grains a head start before the fat from the coconut milk can interfere with water absorption.

Infusion: While the rice is steaming, coconut milk is gently warmed with aromatics such as lemongrass, ginger, and pandan. The partially cooked rice is then tossed with this fragrant mixture, allowing the grains to absorb the coconut richness evenly.

Second steam: The coconut-perfumed rice is returned to the steamer and cooked until tender, fluffy, and fully done. This relatively short final steam preserves the delicate aroma of the coconut milk.

For foolproof nasi lemak with beautifully distinct grains, use sella rice—a parboiled variety of basmati rice available at many Indian and Middle Eastern grocery stores. Parboiling reduces surface starch, helping the grains stay separate even when cooked with rich coconut milk, and also makes the rice more forgiving to slight timing errors. The texture is noticeably different too: nasi lemak made with sella rice is exceptionally fluffy and light, compared to the denser, more cohesive texture of jasmine rice. Neither is inherently better, but if you’re in the basmati camp when it comes to nasi lemak, sella is your best bet.

Nasi Lemak Kukus

Serves 6 | Vegan

August 5, 2025

Summer is for satay

Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks, Wet Market to Table and Plantasia, are available for purchase here and here respectively. Thank you for being here, and enjoy this week’s post! ✨ — Pamelia

The new edition of my cookbook PlantAsia is available for preorder now. Click on the image above for preorder information and links!

The new edition of my cookbook PlantAsia is available for preorder now. Click on the image above for preorder information and links!

When I think of summer, barbecue and satay inevitably come to mind. As a Singaporean, satay is very close to my heart and when I moved to the Netherlands, I realised that it’s also a big part of the culture here, owing to the Indonesian presence. Even though satay is traditionally grilled over charcoal, I don’t always enjoy the fuss of having to start a fire outdoors. If, like me, you want to scratch your satay itch without charcoal, you can fry them in oil in a pan, as I did.

At its core, satay is marinated meat on a skewer. In Singapore, beef and chicken satay are equally common, with pork belly satay becoming increasingly rare. But satay doesn’t always have to star meat; in fact, I find tempeh particularly suited for making satay. In the traditional Javanese dish tempeh bacem, tempeh is simmered in a spiced liquid for an extended period of time, then either shallow-fried or deep-fried. This two-step cooking method allows for flavours to deeply penetrate the tempeh, before enhancing flavour and texture through browning.

While writing PlantAsia, I realised that this was a great way to get flavours into tempeh for satay, compared to using a marinade. I simmer the tempeh in a base made with coconut water, which is not only delicious, but also helps the tempeh brown when grilled. A quick glaze of kecap manis completes the dish.

For accompaniments, Singaporean satay is always served with a peanut dipping sauce that hums with spice and heat, and has lovely nubbly bits of peanut that makes the eating experience a far more interesting one. It’s a simple thing to whip up if you have some rempah sitting in your fridge. In a pinch, you can substitute the rempah with your favourite sambal tumis (fried sambal) and adjust the seasonings to taste. I always add a spoonful of fresh pineapple puree to my satay sauce because I love the freshness it brings to a sauce this rich and brooding. The depth of flavour in satay sauce is always surprising, and even more so when you consider that it’s entirely vegan.

If you have leftover sauce, there are many ways to enjoy it, chief among them being a chunky dressing for blanched vegetables, gado gado-style. Otherwise, it makes a wonderful dip for crisp, raw vegetables like radishes or cucumber!

Tempeh satay

Makes 20 satay | Vegan option

For the tempeh:

400g tempeh, cut into 2cm cubes.

650g coconut water

1 tbsp kicap manis, plus more for brushing or drizzling

2 garlic cloves, finely grated

1 tbsp soy sauce or fish sauce

1/2 tbsp chilli powder

1 bird’s eye chilli, chopped

1 lemongrass stalk, bruised

1 1/2 tsp salt, or to taste

1 tbsp oil, plus more for brushing or frying

In a small pot or saucepan, combine all the ingredients and bring to a simmer over high heat. Reduce the heat to low and simmer uncovered for 20 minutes. Drain the tempeh, reserving the cooking liquid if desired for braising chicken or pork. Set the tempeh aside to cool slightly, then thread onto skewers.

For charcoal grilling: Brush the satay with oil and grill until golden brown on all sides. Brush with kicap manis and continue grilling until charred and caramelised in spots.

For pan-frying: Heat 2–3 tablespoons of oil in a frying pan. Pan-fry the tempeh until golden brown on all sides. Drizzle with kicap manis and continue cooking until charred and well-caramelised.

For the satay sauce:

100g roast peanuts,

110g multipurpose rempah

50g natural peanut butter

25g caster sugar

1½ tablespoons tamarind concentrate

¾ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon coriander powder

½ teaspoon turmeric powder

½ teaspoon cumin powder

240ml water

80g peeled and cored pineapple, cut into chunks

In a small pot, combine all the ingredients except the pineapple. Bring to a simmer on high heat, then turn the heat to low. Cook, stirring frequently, for 3 minutes to meld the flavours. Turn off the heat; the sauce will continue to thicken as it cools. Season with sugar, tamarind concentrate, or salt to taste if desired. Divide the sauce between 2 or 3 serving bowls. Blend the pineapple until smooth, then spoon a dollop of puree into the centre of each bowl.

Chicken or pork satay

Makes 20 satay

July 25, 2025

Kueh kosui

Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every week, you’ll receive historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks, Wet Market to Table and Plantasia, are available for purchase here and here respectively.

Today’s deep dive into kueh kosui is inspired by a request from one of our paid subscribers, Brigette, whose 93-year-old father has been craving this nostalgic sweet—but hasn’t yet found a recipe that hits the mark.

If you’re a paid subscriber and have a topic you'd like me to explore, I’d love to hear from you. Thank you for being here, and enjoy this week’s post! ✨ — Pamelia

KUEH KOSUI / KUIH KASUI / KUEH KO SWEE

Kueh kosui, a sweet steamed cake (or kueh), is beloved in Singapore for how it conveys comfort with just a few humble ingredients. Typically made with a blend of tapioca flour and rice flour, palm sugar for deep, caramel-like sweetness, pandan leaves for fragrance, and a touch of alkaline water for bounce, the mixture is poured into thimble-sized Chinese tea cups and steamed until it sets into a glossy, translucent gel. Once cooled, it’s rolled in grated coconut. The result is a satisfyingly springy yet soft kueh that embodies the holy trinity of Singaporean sweets: palm sugar, pandan, and coconut.

Interestingly, kueh kosui has a cousin in Southeast Asia: kutsinta (also spelled cuchinta or kuchinta), a similarly soft and chewy steamed sweet treat from the Filipino kakanin tradition. Made with unrefined sugar and alkaline water, then topped with grated coconut, its resemblance to kueh kosui hints at a shared regional history shaped by migration and cultural exchange.

ALKALINE WATER

Alkaline water (also called lye water or kansui) has been used across Asia for centuries as a natural chemical agent in food preparation. It gives ramen its yellow tint and elasticity, lends mooncakes their golden-brown crust, and transform century eggs into their characteristic jelly-like texture.

Today, most cooks use commercial alkaline water, but in Southeast Asia, it was traditionally made by burning durian husks to ash, mixing the ash with water, and decanting the alkaline-rich liquid (known as air abu) for use in the kitchen.

When starches like tapioca and rice flour are heated in water, they absorb moisture, swell, and gelatinise, forming a cohesive gel. Raising the batter’s pH with alkaline water alters how the starches react—encouraging stronger bonding between starch chains. The result? A chewy, springy texture.

However, the downside of alkaline water is that it can leave behind a strong whiff that some (including me) find off-putting—and it often comes in large bottles that go unused. I wondered if I could develop a kueh kosui recipe without the use of alkaline water.

STARCHES IN KUEH KOSUI

Many traditional kueh kosui recipes rely on a blend of tapioca and rice flours:

Tapioca flour is high in amylopectin, a branched starch molecule that creates a elastic texture and glossy appearance when heated. It is what gives kueh kosui its signature bounce and translucent sheen.

Rice flour contains amylose in addition to amylopectin. Amylose forms firmer, less elastic gels, providing structure and sliceability while reducing stickiness. However, it also makes the kueh more opaque, so the balance between rice flour and tapioca flour is key.

I tested two versions: one with only tapioca flour, wanting to push its chewiness to the limit in the absence of alkaline water; and the other with a more traditional blend of tapioca flour, rice flour, and alkaline water. The all-tapioca version was translucent but resembled a translucent, gloopy gel at best. It was impossible to slice. The traditional version, on the other hand, steamed up opaque and lacked bounce.

Suspecting the rice flour ratio was too high and the alkaline water too low, I experimented with a few different ratios based on recipes online. Still, the results were disappointing—either too opaque and lacked bounce, or overwhelmed by the alkaline flavour.

WHEAT NOODLES, THE UNEXPECTED INGREDIENT

Noting that some kueh kosui recipes include wheat flour, I began experimenting with it as a substitute for rice flour. Wheat flour contains gluten-forming proteins—gliadin and glutenin—which, when hydrated, form an elastic network that adds structure and chewiness. In kueh kosui, this helps balance the softness of tapioca starch with a bit of resilience. Crucially, because wheat flour contributes more structure than rice flour—thanks to its gluten content—you can use it in smaller amounts to achieve the same chew, which allows for more tapioca flour and hence a more translucent kueh.

It felt like I was finally getting closer to the right texture, but I was still facing issues. When steamed as-is, the batter tended to separate. But when I pre-cooked it, it often ended up over-thickened, making it difficult to level evenly in the moulds:

The breakthrough came from a comment on Dr. Leslie Tay’s ieatishootipost Facebook page, where someone mentioned that her grandmother used boiled mee sua—thin wheat noodles—blended into a paste and added to the batter:

While not a traditional technique found in canonical cookbooks, this idea aligns with other Asian cooking techniques, like adding tangzhong (a pre-cooked flour paste) to bread doughs, or cooking a portion of kueh dough before incorporating this ibu dough (mother dough) into the rest. In kueh kosui, the pre-cooked starch gel:

Thickens the batter while helping to suspend starches evenly—thus reducing separation.

Mimics the effects of alkaline water by promoting enhanced starch swelling, creating bounce and chew.

Improves moisture retention, as in tangzhong breads, helping the kueh stay soft after cooling.

Without mee sua on hand, I used thin Korean wheat noodles which cook just as quickly:

I was thrilled when I sliced into the kueh kosui. It had everything I’d been chasing: a glossy surface that caught the light, a gentle wobble as the knife went through, and a tender, springy bite. There was no harsh, alkaline edge, only the rich flavour of palm sugar.

All it needed was a toss in grated coconut. With so few ingredients in this kueh, I can’t emphasis how important it is to use the freshest grated coconut you can get your hands on. If you can, get it from the market. If opting for frozen, save the half-used bag from your freezer for another dish and go for an unopened one instead.

This kueh is best the day it’s steamed but holds up beautifully in the fridge, staying tender even after a day or two.

KUEH KOSUI

Serves 6 | Vegan

July 18, 2025

Otah tigres

Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every week, you’ll be receiving historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes from me delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks Wet Market to Table and Plantasia are available for purchase here and here respectively. Thank you for being here, and enjoy this week’s post. ✨ — Pamelia

THAT ONE DISH SPOTLIGHT

I had a wonderful time chatting with Shayne Chammavanijakul, a Chicago-based food writer, publisher, and illustrator. She writes that one dish., a weekly newsletter on Asian foodways through the lens of third-culture and hybrid cooking. In her that one dish. spotlight, I chatted about my food writing journey, my earliest food memories, and why Singaporean foodways mean so much to me. Thanks Shayne for having me!

OTAH TIGRES

It’s mussel season in the Netherlands, and while the classic preparation—steamed with white wine and garlic—remains a favourite, there’s always room for novelty. After purchasing a few discounted packs of mussels recently, I steamed them just until they opened and folded the flesh into a mixture of coconut cream, fish, spice paste, and tapioca starch in the style of otah—a fiery, aromatic fish custard traditionally grilled or steamed in banana leaves. While some home-cooked versions include slivers of squid or chopped prawns for texture, I found that mussels make a wonderful addition, their gentle chewiness punctuating the custard’s silky richness. Served with rice or spread on toast for a savoury breakfast, it was both comforting and luxurious.

Mussel otah, steamed and enjoyed as a savoury spread for bread.

Mussel otah, steamed and enjoyed as a savoury spread for bread.After two years of living in the Netherlands, one snack I’ve come to enjoy—almost monthly—is bitterballen, the deep-fried bar staple found on nearly every menu. I’m a part of a walking group that meets every week to walk around our city’s canal and we inevitably end up at the tea house of the park for a drink. Designed for eating with a beer in hand and good conversation on the side, these bite-sized croquettes are usually what we’d order to share.

Crisp on the outside and molten within, each is filled with stewed meat folded into creamy béchamel. They remind me of tigres, a Spanish cousin in the croquette family, made not with meat but with mussels, folded into béchamel, spooned back into their shells, then breaded and deep-fried. Inspired by this, I stuffed my mussel otah mixture into the empty mussel shells. As the exterior crisps in the oil, the inside sets into a custardy filling that is fiery and deeply savoury. It makes a perfect pre-dinner snack. While the original uses breadcrumbs, panko is a lot more satisfying in its crunch and maintains crunchier for longer—an important consideration when you’re feeding a crowd at a party or bringing these for a potluck.

A tip: opt for larger mussels if you can find them. They’re easier to stuff and far more satisfying to eat. I recommend serving them with teaspoons—the best tool for scooping out every last bite of otah.

OTAH TIGRES

If you’re short on time, you don’t have to make the rempah from scratch. Use your favourite sambal—just make sure that it’s of the fried variety (e.g. sambal tumis or sambal badjak) rather than the raw variety, and adjust the seasonings in this recipe to your taste.

Serves 4 to 6

July 9, 2025

Ensaymada doughnuts

Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Every week, you’ll be receiving historical tidbits, personal stories, and recipes from me delivered straight to your inbox. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks Wet Market to Table and Plantasia are available for purchase here and here respectively. Thank you for being here, and enjoy this week’s post. ✨ — Pamelia

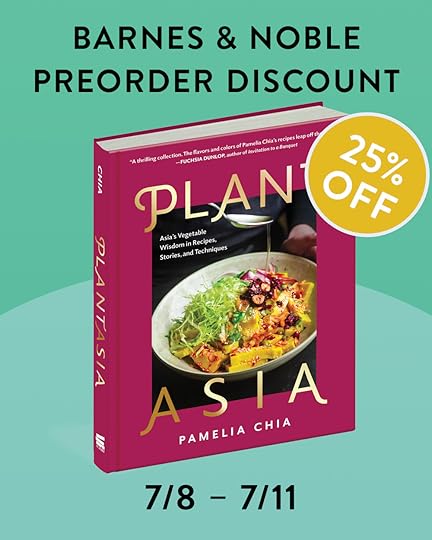

PLANTASIA PREORDER SALE

A new edition of my cookbook PlantAsia is launching in 3 months! This updated release features 88 vibrant, vegetarian recipes inspired by Asia's rich culinary traditions, plus interviews with two dozen acclaimed chefs, food writers, and cookbook authors woven throughout. PlantAsia will transform the way you think about—and cook with—vegetables, bringing more joy and flavour to your kitchen.

For 3 days only, Barnes & Noble is offering 25% off all preorders with the code PREORDER25. If you've been planning to get a copy, now’s a perfect time. Preorders truly matter—they help a book reach more readers and make a big impact on its launch. Thank you so much for supporting my work! (This promotion applies to both free Barnes & Noble Rewards members and Premium Members.)

ENSAYMADA DOUGHNUTS

Last week, we had a heatwave that was absolutely brutal. Our house turned into a greenhouse with its large, double-glazed windows that let the sun in, and even with the fan going full blast, turning the stove or oven on was the last thing on my mind. We ate cold noodles for dinner pretty much all through the week. This week, though, the weather has cooled considerably (a mercy!) and I found myself craving yeasted doughnuts — hot, fluffy, and light. When thinking of what to fill them with, the idea of ensaymada-inspired doughnuts came to mind. I’ve written before about these Filipino brioche-like buns that toe the sweet-savoury line, topped with cream cheese frosting or a sprinkling of sugar, and grated cheese. Just as defining is their pillowy, lighter-than-air texture—and what could be more cloud-like than a freshly fried doughnut?

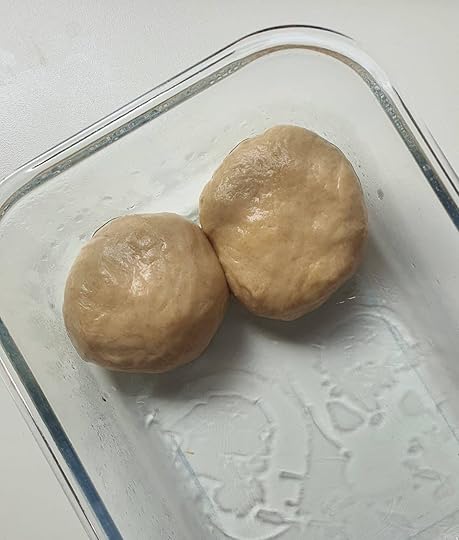

Like ensaymadas, yeasted doughnuts typically begin with a brioche-like dough. The payoff of such a buttery base is a feathery crumb and rich, golden-brown crust. Traditional brioche relies on intensive beating to develop gluten, but since I don’t have a stand-mixer, I went for a more passive approach: a long cold fermentation.

As the dough rises slowly in the refrigerator, yeast consumes sugars and produces carbon dioxide, stretching and expanding the gluten network. Acids and enzymes are also produced, and these break down proteins, further enhancing the extensibility of the dough. This mimics much of what kneading does—just more slowly, more gently, and with far less effort.

My doughnut filling is inspired by an unforgettable slice of Basque cheesecake that I had at Jon Cake in Barcelona a few years ago. It was made with four cheeses—parmigiano reggiano, grana padano, gorgonzola, and mascarpone—and the way the salty, funky sharpness of the aged cheeses was tempered by the creamy backdrop that mascarpone left me inspired. I chose to use mascarpone and Edam cheese and cooked the filling entirely over the stovetop. It was runny and stretchy, with a satisfying cheese-pull effect, but set into something smooth and easy to pipe once chilled.

While this is a fairly straightforward recipe, here are a couple of notes for success:

Use a larger container than you think for the cold bulk ferment. You can’t fully predict how much the dough will expand during its overnight rise. The last thing you want is for it to push past the container lid and dry out at the edges—or worse, overflow entirely.

Proof the doughnuts on squares of parchment paper. Once proofed, the doughnuts are airy and delicate. Transferring them directly from the counter can risk deflating them. Parchment makes the process smoother: you can lower the doughnuts into the hot oil with the paper still attached, then peel it off easily once they’re golden brown.

Fry as close to serving time as possible. The most delicious doughnut will always be the one fried most recently. Even the best will start to languish after a few hours at room temperature. With that in mind, plan your frying as close to serving as you can. Your refrigerator is your friend: if needed, do the final proof in the refrigerator rather than at room temperature to buy more time. Don’t even entertain the thought of frying today and serving tomorrow!

Use the freshest oil you can. This is not the time for old oil. Yes, I usually reuse my oil when deep-frying—throwing it out after one use feels wasteful. However, oil absorbs odours remarkably well, and with doughnuts, you don’t want them tasting of last night’s fish fingers or fries.

Keep your oil at 350°F (175°C). Temperature control is everything. Too hot, and the doughnuts will brown too fast, leaving the insides raw. Too cool, and they’ll come out heavy and greasy. A thermometer takes out the guesswork. The ideal doughnut wears a pale white band around its middle, a mark of perfect frying.

Let them cool before tossing in sugar. Coating doughnuts straight from the fryer means the residual oil will melt the sugar into a sticky glaze. For a light, powdery finish, let the doughnuts cool and drain on a wire rack for 15 minutes before sugaring.

RECIPE

Makes 16 doughnuts

June 27, 2025

Roti prata

Welcome to Singapore Noodles, a celebration of Asian culinary traditions and food cultures. Archived recipes and other content can be found on the index. My cookbooks Wet Market to Table and PlantAsia are available for purchase here and here respectively. Thank you for being here, and enjoy this week’s post. ✨ — Pamelia

Roti prata has always been an important part of my life. For readers unfamiliar with this flatbread, it originates from the Indian paratha (पराठा), a word derived from the combination of “parat” (परत), meaning layers, and “atta” (आटा), meaning flour. This describes a layered, unleavened bread made from wheat flour. The term “roti” is commonly used in both Malay and many South Asian languages to refer to bread or flatbread, while “prata” is a shortened form of the word “paratha.”

The unique texture of roti prata is created by stretching the dough into a thin sheet, then folding or coiling it to form multiple layers before cooking it on a hot griddle. The exterior becomes crunchy due to the caramelization of fat and flour, while the inside reveals membrane-thin layers that provide a pleasant chewiness.

While there are many regional variations of paratha in India, it is regarded primarily as a vehicle for the dishes it accompanies. In Singapore, however, prata is the main event. The curries served alongside—typically mutton or fish curry—are mere footnotes. There are endless permutations of roti prata (or prata for short) you can find across the island, depending on how it is shaped and what it is cooked with. Some examples include tissue prata, where the sheet of dough is placed directly on the griddle and manipulated into a giant cone as it browns; egg prata, where a beaten egg is tucked within the layers; or banana prata, a sweet variation with banana slices that turn gooey as the prata fries. You can also enjoy plain prata simply dipped into a tidy mound of sugar.

Before moving abroad, I lived in Marymount, which has some of the city’s most notable prata spots: Sin Ming Prata, famed for coin prata which are silver-dollar-sized and extra crunchy; Springleaf Prata, which I appreciate for its consistency; and Prata House, where the prata pales compared to the other two but was my go-to for late-night supper spot as a student. It was an affordable breakfast or late-night snack that I enjoyed without much thought—until I moved to Melbourne in 2018 and saw how popular roti was there, often commanding price tags as high as AU$16 in restaurants.

It made me reconsider the value we place on traditional dishes, and realise that roti prata was something I could make at home. What I’ve learnt in the years of experimenting is that you can make great prata without special equipment like a stand mixer and without having to flip the dough, which is often the trickiest part which discourages most from attempting prata.

THE DOUGH

Prata dough is simple—flour, salt, water, some fat, and a sweetener. Some people substitute evaporated milk for water and use condensed milk as the sweetener, but I avoid this because it’s inconvenient to buy a whole tin when only a small amount is needed, and the flavour difference is minimal, especially if you’re going to serve the prata with curry. My recipe includes only flour, salt, water, melted butter, and sugar. If you’re vegan, you can substitute melted coconut oil or neutral oil for the butter.

The idea with roti prata dough is that it needs to be strong and elastic enough to stretch out thinly without tearing—in bread-making terms, the stretched dough should form a giant “windowpane.” While some cooks use a stand mixer to develop this strength and elasticity, time can be just as effective, without the need for elbow grease or machinery. In fact, one of my favourite brioche recipes is a no-knead one from Weekend Bakery, where a 24- to 48-hour rest in the refrigerator compensates for the intensive kneading. The same principle applies to roti prata—the key to a strong, stretchable dough is rest. Your job is simply to mix all the ingredients in a bowl, divide the dough into portions, coat them in oil, and then let them rest overnight.

After running several trials, I’ve noted that the dough’s hydration level is crucial. I used to think prata dough should be quite soft to make it easier to stretch. However, I’ve found that when the dough is too soft, the portioned dough balls tend to “melt” into one another during the overnight rest and tear easily when stretched.

THE STRETCHING

Once rested, the prata dough needs to be stretched out. This is the most important part of the prata-making process: if the dough is not thin enough, you’ll never end up with the shatteringly brittle exterior or requisite tender layers within.

You start by flattening the dough into a thin disc with a rolling pin or the heel of your palm, then stretch it further by rotating it in the air—leading with one hand while the other acts as a fulcrum. This motion is often called “flipping,” but I find the term confuses students in my cooking classes, as they assume the dough must be literally flipped onto its other side. While this is certainly possible with practice, it requires time to perfect. Fortunately, there’s an alternative method: gently stretching the dough out, much like you would with strudel dough.

THE SHAPING AND FRYING

Each stall has its own way of shaping prata. When I lived in Melbourne, the popular style involved pushing the stretched sheet from one end to the other to form a long rope, which is then coiled into a spiral, like a snail’s shell. When flattened, the prata fries up tender and airy in some places, and crisp and flaky in others. Before serving, the prata is pressed between two spatulas in the pan—or clapped between palms on a work surface—until the layers break apart and the cooked roti is fluffed up.

The method that is a little more common in Singapore emphasises a super-crisp, cracker-like shell with fewer layers in between. If you live in Singapore, a good place that specialises in this style of prata is Chindamani Indian Food Stall (I go to the Bishan branch and their prata is photographed at the top of this post!) This shaping style encourages creativity: before folding the prata into an envelope, you could add a beaten egg to form egg prata, banana slices for a sweet variation, or spiced minced meat for murtabak. With both styles of prata, the key is to be generous with the oil in the pan; this produces beautiful blisters and encourages crunch.

Once the dough is made, it keeps in the refrigerator for up to 2 days, so it’s perfect for spontaneous prata breakfasts or curry nights. Leftovers or any extra pratas can be chopped and turned into Sri Lankan kootu… Truly, so versatile.

ROTI PRATA

Makes 4 | VEGAN OPTION