Eric Vickrey's Blog

November 22, 2025

My Fifteen Minutes With Bart Shirley

I had the pleasure of interviewing Bart Shirley for Before They Wore Dodger Blue, a book that is largely about 1970 Spokane Indians—one of the great minor-league teams of all time. Shirley was the club’s starting second baseman. Steve Garvey, Bobby Valentine, and Bill Buckner filled the other three infield spots. The stacked roster also included Davey Lopes, Bill Russell, Charlie Hough, Doyle Alexander, Tom Paciorek, and Geoff Zahn. Almost all of these future big-league stars were part of the Dodgers’ historic 1968 draft class. And their manager was a guy named Tommy Lasorda.

Compared to his younger teammates on the ’70 Indians, 30-year-old Bart Shirley was a grizzled veteran. He had played in parts of four big-league seasons with the Dodgers and Mets over the previous decade. That’s why Lasorda asked him to be a player-coach that year. As I began my reporting for the book, Shirley was one of the first players I contacted. He called me back on July 26, 2024. We spoke for 15 minutes.

From Corpus Christi to AustinBarton Arvin “Bart” Shirley was born on January 4, 1940, in Corpus Christi, Texas. He attended Ray High School, where he set a school record as a senior halfback, averaging nearly eight yards per carry and earning All-State honors. Shirley also starred at shortstop for the Ray baseball team and received bonus offers from multiple major-league clubs. He turned them down and enrolled at the University of Texas in Austin. Shirley said he chose Texas because legendary football coach Darrell Royal said he’d let him play baseball.

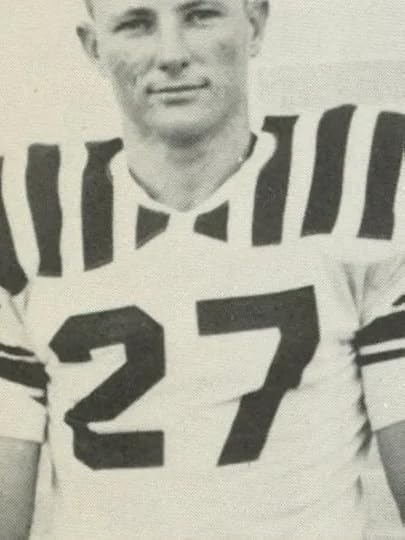

Bart Shirley at Ray High School in Corpus Christi.

Bart Shirley at Ray High School in Corpus Christi. Shirley majored in business administration and played for the freshman football and baseball teams. At 5-foot-10 and 180 pounds, the blond-haired, square-jawed Texan possessed the build of a bowling ball. Some likened him to a young Mickey Mantle. “The more clothes he takes off the bigger he looks,” said one Longhorns coach.

As a sophomore, Shirley moved up to varsity and played in the Cotton Bowl. During our conversation, he recalled the thrill of returning a punt on national television. In the spring of 1961, Shirley made the All-Conference baseball team as a shortstop for the Longhorns and then played semipro ball that summer in Rapid City, South Dakota. Dodgers scout Hugh Alexander had followed Shirley’s steady progress and offered him a bonus of $60,000. It doesn’t sound like much, in retrospect, but consider this: Willie Mays—the highest paid major leaguer at the time—earned $85,000 that year. Shirley accepted the Dodgers’ offer and bought his mother a new house.

Bart Shirley’s Pro Baseball CareerThe Dodgers thought highly enough of Shirley to have him skip the lower minors, assigning him to the Double-A Atlanta Crackers. He didn’t hit much that first year, producing a slash line of .239/.292/.326. Nevertheless, the Dodgers promoted him to Triple-A Omaha the following season. He performed better at the plate a bided his time with the Dodgers’ other Triple-A club, the Spokane Indians, over the next two seasons. Shirley would get to know Spokane very well.

In September 1964, the Dodgers promoted Shirley to the big club when rosters expanded. “I’ll never forget the first time I went to bat with the Dodgers,” he recalled. “There was this lady sitting by our bat rack, and she said, ‘Come on Bart, get a hit.’ It was Doris Day.”

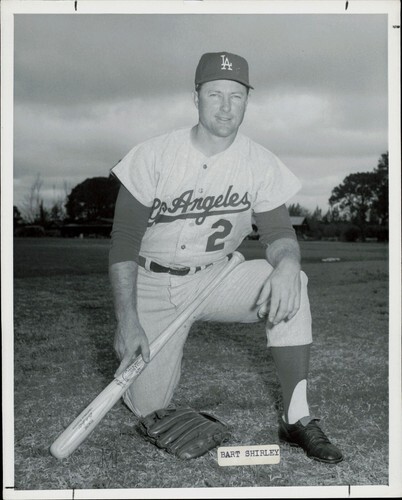

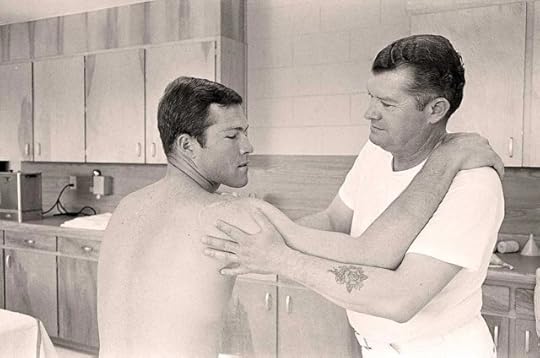

Infielder Bart Shirley played in parts of three seasons with the Dodgers in the 1960s.

Infielder Bart Shirley played in parts of three seasons with the Dodgers in the 1960s.Eleven days later, Shirley experienced the thrill of playing in front of hundreds of family and friends in Houston against the Colt .45s at Colt Stadium. He tripled home a run, walked twice, and drove in a second run with a groundout. In 62 at-bats down the stretch, he batted .274.

Except for a couple more cups of coffee in Los Angeles and a brief stint with the New York Mets, Shirley spent most of the next six seasons in Spokane. He played in 997 games with the Indians, a record that still stands today. “There was an Italian family named Saccmmanno who took in several players,” recalled Shirley. “They fed us and took care of when we were at home. It was a great town. I enjoyed my stay there.”

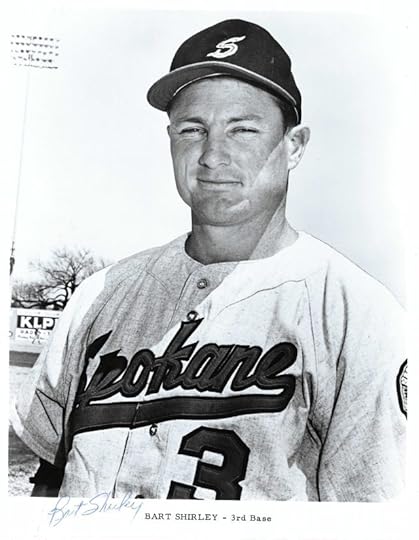

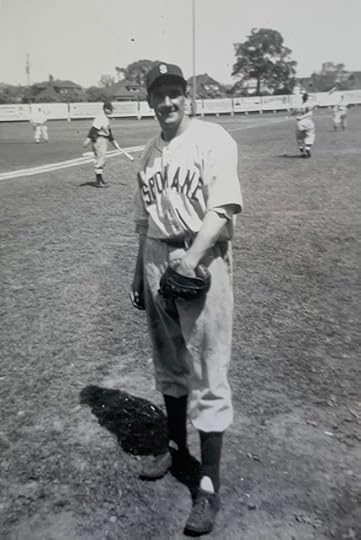

Bart Shirley holds the Spokane Indians franchise record with 997 games.

Bart Shirley holds the Spokane Indians franchise record with 997 games. A versatile infielder who could capably man second, third, or shortstop, Shirley hit .263 with 29 home runs over 10 seasons in the minors. “He was like a dad in the locker room,” said former Spokane clubhouse boy Kent Schultz. “He didn’t make any mistakes and was a team player. Not a rah-rah guy but consistent and professional.”

Shirley’s double-play partner from 1969-70, Bobby Valentine, found him to be the ideal mentor. “Bart was a spectacular person,” said Valentine. “To have him as a second baseman when I was trying to learn shortstop was a god-send.”

Bart Shirley with the 1970 Spokane Indians.

Bart Shirley with the 1970 Spokane Indians.For most of his professional career, Dodgers star shortstop Maury Wills blocked Shirley’s path to the majors. In 75 big-league games, the Corpus Christi native batted .204 and never hit a home run. One of his 33 major-league hits came against Bob Gibson during his historic 1968 season when he posted a 1.12 ERA. “I think I hit a base hit up the middle, got my bat around,” Shirley remembered. “He could bring it up there pretty quick.”

Bart Shirley Returns HomeShirley spent his last two seasons as a player in Japan with the Chunichi Dragons. He then managed Single-A teams for three seasons in the Dodgers minor-league chain before returning home. Following his baseball career, Shirley worked in the insurance business and remained active in his church throughout his life. He and his wife, Victoria, had two children.

After his baseball career, Bart Shirley spent the rest of his life in his hometown of Corpus Christi.

After his baseball career, Bart Shirley spent the rest of his life in his hometown of Corpus Christi. During our brief conversation, Shirley said he once hit a hole-in-one during a round of golf with Duke Snider. He recalled how Don Drysdale would take the Dodgers young players golfing at the Riviera Country Club and cover the bill. But the most memorable aspect of his time in The Show? “The highlight of my career was sitting on the bench watching Koufax pitch,” said Shirley.

I interviewed dozens of former players for this project, and none were more humble than Bart Shirley. He was not a man of many words, but he spoke fondly of the memories he carried from his professional baseball career.

I had looked forward to sending Bart a copy of the book. Sadly, he died on November 19, 2025—18 days before its release. He was 85. Although I wish he could have read the book, the reality is he didn’t need to. He lived it.

The post My Fifteen Minutes With Bart Shirley appeared first on Eric Vickrey.

September 25, 2025

John Werhas and the Origin of Peaches

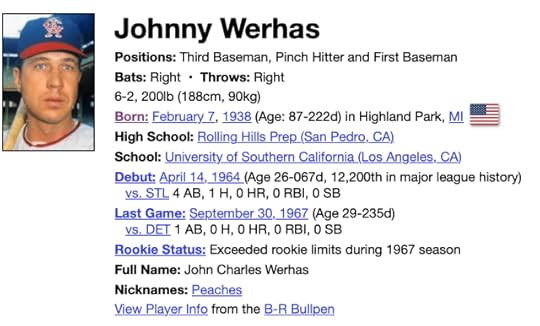

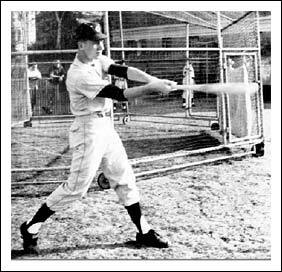

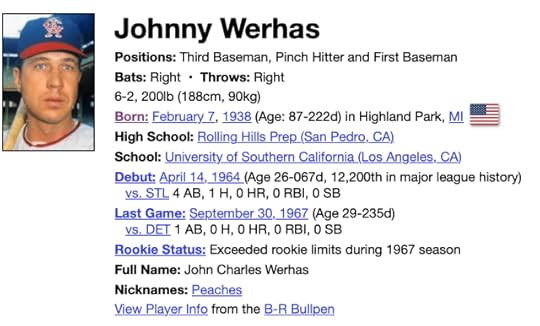

I had the pleasure of interviewing former major leaguer John Werhas for my forthcoming book, Before They Wore Dodger Blue. He offered insights from his time with the Dodgers and Triple-A Hawaii Islanders and shared anecdotes about his longtime friend, Tommy Lasorda. During our conversation, I asked Werhas about the nickname listed on his Baseball Reference page: “Peaches.” Although it didn’t fit in the book, it’s a fun story.

Two-Sport Star at USC

Two-Sport Star at USCWerhas possessed tremendous athleticism from an early age. After graduating from Rolling Hills Prep High School in San Pedro, California, he starred in both baseball and basketball at USC. He enrolled on a basketball scholarship but preferred baseball. “I desperately wanted to make it to the big leagues,” recalled Werhas. “That was everything that drove me as an individual.”

John Werhas played forward for the USC Trojans and was drafted by the Lakers.

John Werhas played forward for the USC Trojans and was drafted by the Lakers. Werhas, a third baseman, acquired his fruity moniker during a baseball game between the Trojans and team of marines at Camp Pendleton. Earl Wilson, a member of the Camp Pendleton squad, attempted to advance from first to third on a single. When the outfielder’s throw landed in Werhas’s glove, Wilson was several strides from the base. Instead of sliding, the future 20-game winner jumped into Werhas, his spikes causing a large gash to his left knee. Werhas responded by throwing the ball at Wilson, and the two engaged in a brief scuffle. “The stadium was full of marines,” recalled Werhas, “and they started yelling at me and calling me Peaches.” After the game, USC coach Rod Dedeaux had a little fun with Werhas and wrote “Peaches” on his warmup jacket.

John Werhas played third base under legendary coach Rod Dedeaux at USC. Pro Baseball Career

John Werhas played third base under legendary coach Rod Dedeaux at USC. Pro Baseball CareerThe Los Angeles Lakers drafted Werhas in 1960, but he declined their modest offer. Instead, he pursued his dream and signed with the Dodgers for $20,000. In Vero Beach the following spring, clubhouse attendant Jim Muhe unpacked Werhas’s gym bag and saw the warmup jacket inscribed with “Peaches.” When a Baseball Digest reporter asked the rookie if he had any nicknames, Muhe piped up and said, “Yeah, his nickname is Peaches.” Werhas asked the sportswriter not to write it down. The scribe ignored the request. “Once it gets in here,” promised the reporter, “you can’t get it out.”

Werhas went on to play 13 seasons of affiliated ball, including parts of three campaigns with the Dodgers and Angels. He owned a meager .173 batting average in 168 major-league at-bats. But in the minors he performed well, accumulating 1,368 hits and 141 home runs, mostly at the Triple-A level.

Looking back, Werhas insisted no one ever really called him “Peaches.” However, the nickname Dedeaux and Muhe perpetuated did show up in a few newspaper stories early in his career. Today, Baseball Reference lists it on Werhas’s page. It turns out the Baseball Digest reporter was right. Once the publication printed it, the name stuck.

The post John Werhas and the Origin of Peaches appeared first on Eric Vickrey.

John Werhas and the Origin of a Fruity Nickname

I had the pleasure of interviewing former major leaguer John Werhas for my forthcoming book, Before They Wore Dodger Blue. The former Dodgers third baseman offered insights from his time with the Dodgers and Triple-A Hawaii Islanders and shared anecdotes about his longtime friend, Tommy Lasorda. During our conversation, I asked Werhas about the nickname listed on his Baseball Reference page: “Peaches.” Although it didn’t fit in the book, it’s a fun story.

Werhas grew up in the Detroit suburb of Highland Park. Naturally, he became a Tigers fan. He spent his childhood cheering on the likes of Hal Newhouser, Harvey Keunn, George Kell, and Al Kaline at Briggs Stadium. The summer after Werhas’s ninth-grade year, his family moved to San Pedro, California.

Werhas sprouted to 6-foot-2 and possessed tremendous athleticism. After graduating from Rolling Hills Prep High School, he starred in both baseball and basketball at USC. He enrolled on a basketball scholarship but preferred baseball. “I desperately wanted to make it to the big leagues,” recalled Werhas. “That was everything that drove me as an individual.”

John Werhas played forward for the USC Trojans and was drafted by the Lakers.

John Werhas played forward for the USC Trojans and was drafted by the Lakers. Werhas, a third baseman, acquired the moniker “Peaches” during a baseball game between the Trojans and team of marines at Camp Pendleton. Earl Wilson, a member of the Camp Pendleton squad, attempted to advance from first to third on a single. When the outfielder’s throw landed in Werhas’s glove, Wilson was several strides from the base. Instead of sliding, the future 20-game winner jumped into Werhas spikes high, causing a large gash to his left knee. Werhas responded by throwing the ball at Wilson, and the two engaged in a brief scuffle. “The stadium was full of marines,” recalled Werhas, “and they started yelling at me and calling me peaches.” After the game, USC coach Rod Dedeaux had a little fun with Werhas and wrote “Peaches” on his warmup jacket.

John Werhas played third base under legendary coach Rod Dedeaux at USC.

John Werhas played third base under legendary coach Rod Dedeaux at USC. The Los Angeles Lakers drafted Werhas in 1960, but he declined their modest offer and instead signed with the Dodgers for $20,000. In Vero Beach the following spring, clubhouse attendant Jim Muhe unpacked Werhas’s gym bag and saw the warmup jacket inscribed with “Peaches.” When a Baseball Digest reporter asked the rookie if he had any nicknames, Muhe piped up and said, “Yeah, his nickname is Peaches.” Werhas asked the sportswriter not to write it down. The scribe ignored the request. “Once it gets in here,” promised the reporter, “you can’t get it out.”

Werhas went on to play 13 seasons of affiliated ball, including parts of three campaigns with the Dodgers and Angels. Although he managed a meager .173 batting average in 168 major-league at-bats, he accumulated 1,368 hits and 141 home runs in the minors, mostly at Triple A.

In retrospect, Werhas insisted no one ever really called him “Peaches.” However, the nickname Dedeaux and Muhe perpetuated did show up in a few newspaper stories early in his career.

It turns out the Baseball Digest reporter was right. The nickname stuck. More than a half-century later, “Peaches” remains etched into John Werhas’s story.

The post appeared first on Eric Vickrey.

September 13, 2025

Mel Cole: From Guadalcanal to Spokane

Mel Cole arrived at Spokane Indians spring training in early April 1946 unsure if he had a future in baseball. After all, it had been nearly five years since he had last played professionally. Like millions of Americans, Cole had spent the previous four years serving his country during World War II. With the war over, he joined thousands of other returning servicemen who attempted to resurrect their baseball dreams. Cole hoped to make Spokane’s roster that spring as a catcher. He could not have predicted that on the eve of opening day, he would be anointed manager.

“Can’t Miss” ProspectMelvin Chester “Mel” Cole, a native of Stockton, California, inherited a love of baseball from his father, Chester, a railroad conductor on the Southern Pacific Railroad. At age 16, Cole led the Sacramento American Legion team to the Little World Series in Gastonia, North Carolina. Two years later, legendary New York Yankees scout Joe Devine—the same West Coast talent hawk who signed Joe DiMaggio—inked Cole to a professional contract. Devine called Cole a “can’t miss” prospect.

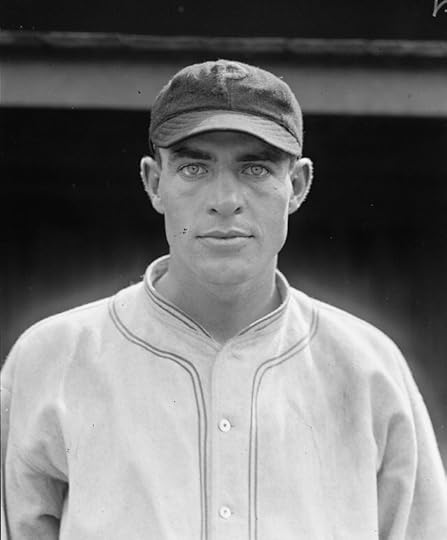

The Yankees assigned Cole to a Class-D affiliate in El Paso, Texas, for the ’37 season. Playing primarily shortstop, he batted .315, made the circuit’s All-Star team, and set a league record by hitting safely in 26 consecutive games. Over the next four seasons, Cole inched up the Yankees’ minor-league ladder, spending time in Joplin, Lewiston, Wenatchee, Idaho Falls, and Tacoma. At each stop, he showed defensive versatility, logging time at shortstop, third base, outfield, and catcher.

Cole played for the Wenatchee Chiefs in 1939 and ’40.Military Service

Cole played for the Wenatchee Chiefs in 1939 and ’40.Military ServiceOn May 8, 1942, Cole enlisted in the Navy. He reported to Sand Point Naval Training Center in Seattle, where he played ball on the base team alongside future Spokane Indians teammate Levi McCormack. In October 1943, Cole set sail for the South Pacific on the USS Hammondsport. He spent the next 18 months in the Pacific Theatre, including time in Guadalcanal, serving an Aviation Machinist Mate 1st Class. During his stint overseas, Cole played and managed a Navy ball team. He also filled out his frame. A fellow soldier told a reporter back home that Cole had become “husky young man in contrast to the anemic looking individual who used to play on high school team.”

Crew of the USS Hammondsport in 1945.

Crew of the USS Hammondsport in 1945. Upon returning stateside, Cole spent the winter working as a railroad switchman. But his desire to make a living playing baseball hadn’t wavered. On March 13, he signed a contract with the Spokane Indians, an independent Class-B club in the Western International League. At 27, Cole was old for a prospect, so he fudged his birthday on a publicity questionnaire he completed before the season. He indicated a birth year of 1920—two years after his actual birth date.

Mel Cole made himself two years young on this publicity survey from January 1946.Back to Baseball in ’46

Mel Cole made himself two years young on this publicity survey from January 1946.Back to Baseball in ’46In early April, Cole traveled to Marysville, California, for three weeks of spring training with the Indians. A hand injury hampered his play, but he still managed to win one of the team’s two catching jobs. When camp broke, Cole and his new teammates bussed from Marysville to Spokane. During the two-day trek, manager Glenn Wright—a former star shortstop with the Pirates and Dodgers—went on a bender. “Glenn was a terrific guy,” recalled pitcher Gus Hallbourg years later. “But he was drunk from the time we left Marysville to when we got back to Spokane.”

Former Pirates shortstop Glenn Wright was hired to managed the Spokane Indians in ’46 but lost his job before opening day.

Former Pirates shortstop Glenn Wright was hired to managed the Spokane Indians in ’46 but lost his job before opening day. The team arrived in Spokane on April 23. Over the next two days, Wright disappeared. The night before the home opener, the team’s incensed owner, Sam Collins, fired him and named Cole player-manager.

Managing the Spokane Indians“I know I’m a lucky fellow to get this job, and I want the people to know I’ll do my best and so will the players,” Cole told reporters. “If I didn’t think I could handle the job, I wouldn’t have accepted it. The boys are going to hustle, and we’re going to win.”

After losing eight of their first 11 games, the talent-laden Indians caught fire. By mid-June, they stood firmly in the thick of the Western International League pennant race. Cole didn’t contribute much on the field, managing just seven hits in 41 at-bats for a .171 average. His dream of playing in the majors or Pacific Coast League looked bleak, but carving out a career as a manger remained a possibility. Over the first two months of the season, he proved himself a capable leader. He also showed a fiery temper. Umpires ejected Cole on three occasions for arguing. The third offense earned him a three-game suspension and $10 fine.

Mel Cole on June 22, 1946.

Mel Cole on June 22, 1946.Former Brooklyn Dodger Ben Geraghty filled in while Cole served his suspension. A couple of days after his return, Cole piloted Spokane to a dramatic come-from-behind victory over the Salem Senators on June 23.

Tragedy StrikesThe next morning, the Indians boarded a coach bus and traveled west across Washington state for their next series in Bremerton. The bus reached Snoqualmie Pass in the early evening hours as a light rain fell from the dusk sky. Just over the pass, an oncoming vehicle forced the bus off the road. It tumbled down a steep ravine, catching fire as it rolled. The crumpled coach came to rest 300 feet below the road.

What remained of the Spokane Indians bus post-crash.

What remained of the Spokane Indians bus post-crash.Mel Cole and eight of his teammates lost their lives. The twenty-seven-year-old skipper and World War II veteran was buried in East Lawn Memorial Park in Sacramento. He left behind a pregnant widow named Marian. She named her some Melvin Jr.

You can read more about the 1946 Spokane Indians in my book, Season of Shattered Dreams. I have also written several posts about other members of the team which can be found under the blog tab.

The post Mel Cole: From Guadalcanal to Spokane appeared first on Eric Vickrey.

September 7, 2025

Tom Seaver: Dodgers Draft Pick

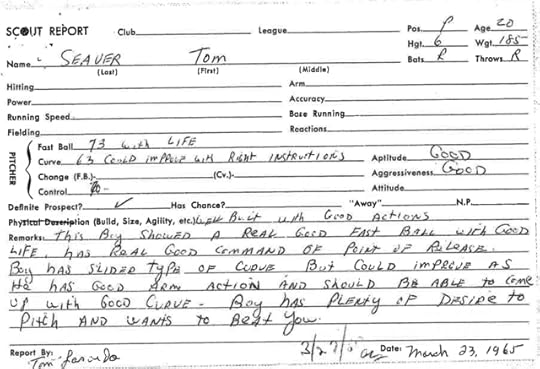

In 1965, the Los Angeles Dodgers—based on the reports of scout Tommy Lasorda—selected USC pitcher Tom Seaver in the 10th round of Major League Baseball’s inaugural amateur draft. Had he signed, Seaver would have likely joined a ’67 Dodgers rotation that included Don Drysdale and Don Sutton. LA very well may have won another championship or two with Tom Terrific at the top of the rotation. Instead, Seaver turned down the Dodgers’ meager offer and later became enshrined in Cooperstown as a New York Met.

Lasorda’s Scouting Report of Tom SeaverSeaver first caught scouts’ attention in the spring of ’64 as a freshman at Fresno City College, where he posted an 11-2 record and 1.78 ERA. He rebuffed several major-league teams that summer, opting to continue his college education. As a sophomore, Seaver transferred to USC. The Fresno native pitched for legendary coach Rod Dedeaux and pursued dentistry as a fallback plan.

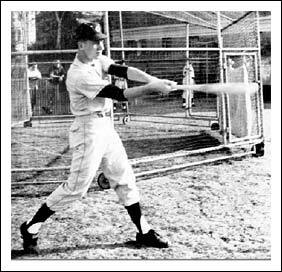

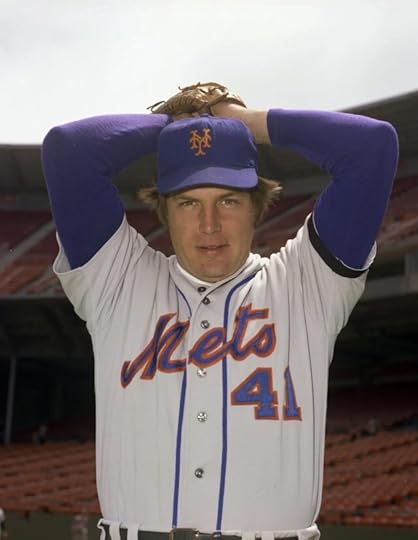

Tom Seaver hurling for the USC Trojans.

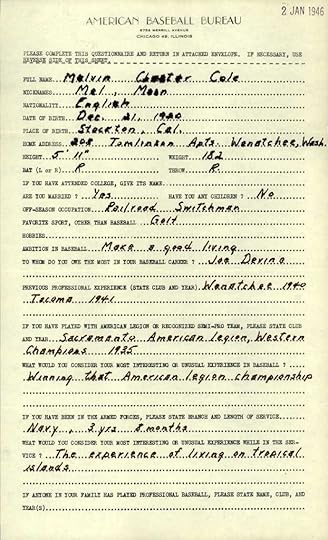

Tom Seaver hurling for the USC Trojans.On March 20, 1965, Seaver scattered six hits in the Trojans’ 4-2 victory over the University of Arizona. Three days later, Lasorda filed his scouting report on Seaver. On a 60-80 scale, Lasorda graded the righty’s fastball as 73, gave his curve a 63, and rated him as a “definite prospect.” Under the remarks section, Lasorda wrote that Seaver had “plenty of desire to pitch and wants to beat you.”

Tommy Lasorda’s scouting report of Tom Seaver from March 23, 1965.Dodgers Draft Seaver

Tommy Lasorda’s scouting report of Tom Seaver from March 23, 1965.Dodgers Draft SeaverSeaver finished his sophomore season with an outstanding 10-2 record and 2.47 ERA. After the Dodgers picked him in the 10th round of the amateur draft that June, the two sides never came close an agreement. In his autobiography, The Artful Dodger, Lasorda seemed perplexed as to why the Dodgers didn’t sign the USC product. “Seaver contends the Dodgers didn’t offer him a contract as a favor to Dedeaux, forcing him to pitch in college another year,” wrote Lasorda. “I don’t know why the Dodgers didn’t sign Seaver, but I certainly don’t believe it was because he was playing at USC.”

Tommy Lasorda and USC coach Rod Dedeaux.

Tommy Lasorda and USC coach Rod Dedeaux. The Dodgers did in fact make Seaver an offer, but it was far less than his asking price of $50,000. Although his salary demand sounds like a pittance in retrospect, only six players received a bonus higher than $40,000 that year. Each of the six were either first- or second-round picks.

“When I asked for $50,000, I think they laughed,” Seaver later recalled. “They thought half of that was too much.” Although he claimed ignorance in his autobiography, Lasorda allegedly told Seaver, “good luck in your dental career.”

Mets Win the LotteryBecause Seaver didn’t sign with the Dodgers, he re-entered the amateur draft in January 1966. The Braves selected him in the first round of the secondary phase (a separate selection process for players who had previously been drafted but did not sign). Altanta signed him a month later. Commissioner William Eckert voided the contract, however, because Seaver signed after the Trojans’ season had already begun. MLB teams received the opportunity to match Atlanta’s $51,000 offer in a lottery. The Indians, Phillies, and Mets participated in the lottery with the Mets being chosen out of a hat.

Seaver had no need for dental school. He would go on to win 311 games, including 198 with the Mets, over the course of his 20-year career. In ’67, the Dodgers fell to eighth place following Sandy Koufax’s retirement, and Seaver won the NL Rookie of the Year Award. Seaver then led the ’69 Miracle Mets to a championship and proceeded to win three Cy Young Awards during the ’70s. The Dodgers, meanwhile, didn’t win their next title until ’81.

For another “what if” scenario from the inaugural draft, check out my post, Johnny Bench: Almost a Cub.

The post Tom Seaver: Dodgers Draft Pick appeared first on Eric Vickrey.

September 3, 2025

Bob Kinnaman and a Once-Promising Career

In 1941, Bob Kinnaman won 22 games for the Spokane Indians. At age 24, his budding baseball career appeared full of promise. But like so many Americans, Kinnaman put his personal aspirations on hold to serve his country during World War II. Postwar, he attempted to pick up where he left off, returning to the minor-league Indians for the ’46 season. Tragically, the lives of Bob Kinnaman and eight of his teammates came to a tragic end that summer.

ChildhoodJosiah “Joe” and Mary (née Puhn) Kinnaman welcomed their first and only son, Robert Earl “Bob” Kinnaman, on March 21, 1917, in Elma, Washington. Bob had two older sisters—Hazel and Dorothy. Joe worked for the Saginaw Logging Company, one of the many lumber companies in western Washington state. In the 1920s and early ’30s, the Kinnamans lived in a logging camp, a rough and tumble community comprised mostly of single men who worked 10-hour days. According to the 1930 census, Mary worked at a general store.

Bob grew up hunting, fishing, and playing sports. He possessed a great sense of humor and loved to joke around. In the mid 1930s, the Kinnamans moved to Brooklyn, Washington, in rural Pacific County. Bob attended North River School in nearby Cosmopolis, where he excelled in football, basketball, and baseball. During summers, he played baseball for a local Grange Hall team coached by his father.

College CareerIn 1935, Kinnaman enrolled at Washington State College, where he joined Sigma Alpha Epsilon fraternity and played baseball for the Cougars. As a pitcher on the freshman team, the righty played with future Spokane Indians star Levi McCormack, one of six players who would survive the ’46 tragedy. As a sophomore, Kinnaman made the Pacific Coast Conference All-Star team. He finished his college career with a stellar 19-6 record.

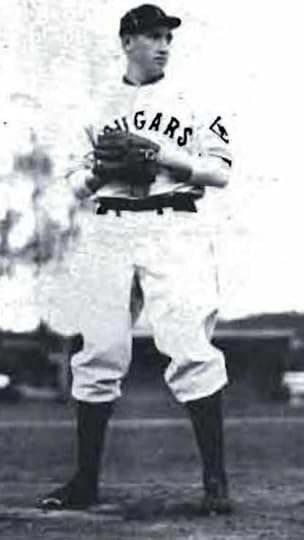

Bob Kinnaman with the Washington State Cougars.Turning Pro

Bob Kinnaman with the Washington State Cougars.Turning ProIn the summer of ’39, Kinnaman signed with the Twins Falls Cowboys in the Class-C Pioneer League. He pitched in seven games, registering a 3-3 record and 3.60 ERA. A year later, he moved up to Class-B Spokane, where accrued a 6-1 record and 3.89 ERA pitching mostly in relief. Kinnaman’s ’40 season included a seven-inning no-hitter against the Salem Senators and a horrific injury in which he lost eight teeth—the result of being struck by a line drive off the bat of future big leaguer Nanny Fernandez. Fernandez hit the ball so hard that the Spokane infielders turned a twin killing on the play.

Bob Kinnaman (left) relaxes with some of his Spokane teammates.

Bob Kinnaman (left) relaxes with some of his Spokane teammates. That offseason, Kinnaman stayed in Spokane and worked as a milkman at Inland Empire Dairy. He returned to the Indians in ’41 joined the starting rotation, logging 246 innings while compiling an outstanding 22-6 record and 134 strikeouts for the league-champion Indians. The Seattle Rainiers and Detroit Tigers expressed interest in Kinnaman that summer. “It’d be pretty nice to get peddled upstream to see if you’ve really got it on the ball to earn the kind of money they’ll pay up there,” Kinnaman told the Spokane Chronicle in August 1941.

Bob Kinnaman is in the second row, fourth from left. Military Service

Bob Kinnaman is in the second row, fourth from left. Military ServiceOn December 20, just 13 days after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, Indians owner Bill Ulrich sold Kinnaman’s contract to Portland of the PCL for $5,000. He’d be pitching just a short drive from his hometown. But before Kinnaman ever got the chance to suit up for the Beavers, he joined the millions of Americans who enlisted in the war effort. He attempted to join the Navy with McCormack, but the Navy rejected him because of his missing teeth. Instead, Kinnaman joined the Army’s 333rd Engineer Special Service Regiment.

Over the next year, he bounced around to several Army bases across the country, working on various construction projects. According to Kinnaman’s great niece, Lisa Johnson, he wrote in family letters that he achieved expert status in shooting drills, likely the result of his time hunting growing up. In 1943, the Army sent him to Europe, where he served for 29 months.

Bob Kinnaman with his mother and grandfather. ’46 Spokane Indians

Bob Kinnaman with his mother and grandfather. ’46 Spokane IndiansIn 1946, the soon-to-be 29-year-old Kinnaman joined the thousands of returning servicemen who resumed their baseball careers. Because he never pitched for Portland, his contract reverted back to the Spokane Indians. Kinnaman pitched under Casey Stengel with the Oakland Oaks that spring before being optioned back to Spokane. The 5-foot-11, 175-pound hurler joined the Indians starting rotation, going 6-4 with a 3.16 ERA through his first 14 outings.

Bob Kinnaman with the ’46 Spokane Indians.

Bob Kinnaman with the ’46 Spokane Indians.On June 24, the Indians team bus went off the road near Snoqualmie Pass in the Cascade mountains and tumbled down a 300-foot ravine. Kinnaman and eight of his teammates were killed. At the time of the accident, he was dating woman named Ruby Roberts. The couple had planned to announce their engagement later that summer. A week after the bus crash, Joe Kinnaman died suddenly. According to Johnson, the family believed he died of a broken heart after the devastation of his son’s untimely passing.

To read more about Bob Kinnaman and the 1946 Spokane Indians, check out my book Season of Shattered Dreams.

The post Bob Kinnaman and a Once-Promising Career appeared first on Eric Vickrey.

June 5, 2025

Johnny Bench: Almost a Cub

There are some things that seem to go naturally go hand in hand. Gastronomically speaking, there’s spaghetti and meatballs, chili and cornbread, and my personal favorite—peanut butter and jelly. Baseball-wise, Stan Musial is synonymous with the Cardinals, Roberto Clemente with the Pirates, and Johnny Bench with the Reds. But the latter pairing almost never came to be. If Billy Capps had his way, Johnny Bench would have been a Chicago Cub.

Capps spent 61 years in professional baseball—23 as a minor-league player and manager and 38 as a scout with the Cubs.1 In 1965, he was just a few years into his scouting career. One spring afternoon, he was driving the backroads of Oklahoma when he happened across a high school game in the tiny town of Binger, population 600. Capps was instantly enamored with the home team’s catcher. The solidly built youngster had a cannon for an arm. As a hitter, the ball jumped off his bat. Capps quickly realized he had unearthed a gem. His name was Johnny Lee Bench.

Capps eagerly filed a report to his supervisor, who traveled to Oklahoma to see Bench for himself. When he got there, he watched Bench go 1-for-4. Perhaps Capps had oversold the kid. There was nothing about his play that screamed first-round draft pick. Bench’s performance that particular day was deceiving, however. It just so happened that he had just returned from his senior class trip and hadn’t played in nearly two weeks. He was a bit rusty. Capps suggested that his supervisor stay and watch the next day’s game. “No, I’ve got other players to see,” he said. The Cubs, like other teams, were trying to gather information on as many players as possible for the upcoming inaugural draft that June. The next day, while the supervisor was off scouting another prospect, Bench returned to form. He went 4-for-4 with two home runs and a pair of doubles.

[image error]Scout Billy Capps, who later signed Kerry Wood, recommended the Cubs draft Johnny Bench. His bosses didn’t listen.Capps wasn’t the only scout aware of Bench’s talent. The Reds’ scouting director, Jim McLaughlin, had heard about him at a meeting with some other scouting directors. He sent two of his area scouts, Tony Rubello and Bob Thurman, to Binger. The pair saw Bench play two games. He got a couple of hits, but what really wowed the talent hawks was his arm. Bench had developed incredible throwing ability with the help of his father, who’d stand a hundred feet behind second base and challenge Johnny to throw the ball on a line.

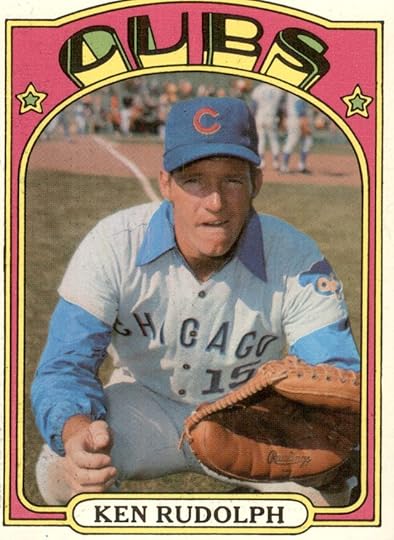

Capps implored his bosses in the Cubs front office to take Bench in the first round. But come draft day, they didn’t want to waste a pick on a guy who they figured would be available much later. Instead, they chose prep pitcher Rick James with the sixth overall pick. With the 16th pick, Cincinnati grabbed third baseman Bernie Carbo, who would go on to have a 12-year big-league career. The Cubs had a second shot at Bench in round two but opted for a college catcher, Ken Rudolph, instead. The Reds called Bench’s name with their second-round pick, 36th overall.

Bench didn’t even know he was on the Reds’ radar. “I was totally surprised Cincinnati drafted me because I hadn’t talked to any of their scouts and I hadn’t expected anyone to pick me that hight,” he said years later. He signed for $6,000 plus college tuition, which amounted to $14,000.

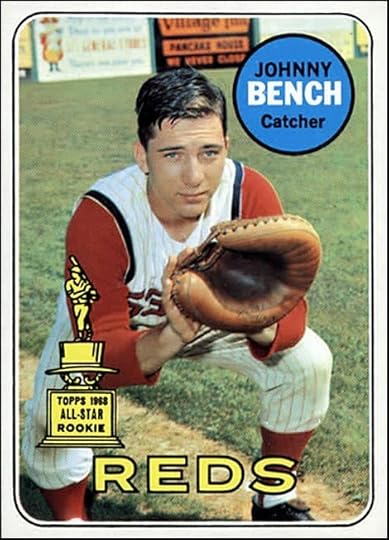

The Red drafted Johnny Bench in the second round of the 1965 draft.

The Red drafted Johnny Bench in the second round of the 1965 draft.The Cubs would quickly come to regret passing on Bench. Three years later, he won the Rookie of the Year Award. Two years after that, he won the first of his two MVP Awards. Over the course of his 17-year Hall-of-Fame career, Bench made 14 All-Star teams and won 10 Gold Glove Awards. He helped the Big Red Machine win two championships and took home World Series MVP honors in 1976. Bench is widely considered the best catcher in baseball history and is on the Mount Rushmore of greatest Cincinnati Reds of all-time.

Johnny Bench, 1968 ROY.

Johnny Bench, 1968 ROY.Ken Rudolph, on the other hand, became a career backup. In his nine big-league seasons, he hit .213 with six home runs. Bench hit more home runs in the postseason (10) than Rudolph did for his entire career. A year later, the Mets made a similarly regrettable decision, selecting prep catcher Steve Chilcott over Arizona State outfielder Reggie Jackson with the first overall pick.

The Cubs selected college catcher Ken Rudolph over Johnny Bench in the 1965 draft.

The Cubs selected college catcher Ken Rudolph over Johnny Bench in the 1965 draft.How different would things have been for Bench and the Cubs had the team followed Capps’ advice? Bench answered that question in a 2012 interview: “People say, ‘What would have happened if you would have become a Cub? I said, ‘I know one thing, they would have won a World Series by now.’ I felt so bad for Billy Capps. He had found me, and he loved me, and I didn’t become a Cub.”

Ron Santo and Johnny Bench could have been teammates had the Cubs followed the advice of scout Billy Capps.Capps was Midwest scout of the year in 1989 and was inducted into the Texas Scouts Hall of Fame in 1999. Kerry Wood was among the players he signed.

Ron Santo and Johnny Bench could have been teammates had the Cubs followed the advice of scout Billy Capps.Capps was Midwest scout of the year in 1989 and was inducted into the Texas Scouts Hall of Fame in 1999. Kerry Wood was among the players he signed.  ︎

︎The post Johnny Bench: Almost a Cub appeared first on Eric Vickrey.

May 30, 2025

The 1982 Cardinals’ Historic Pitching Streak

The 1982 Cardinals are most remembered for their blistering foot speed and impervious defense. After all, the World Champs stole 200 bases and featured Gold Glove-caliber defenders at every infield position. Heck, the book I wrote about the team is called Runnin’ Redbirds. But the Cards may not have won the NL East that year had it not for an historic run of pitching down the stretch. The ’82 Cardinals pitching staff allowed two earned runs or fewer over 11 consecutive games in mid September. Since 1969, only four other teams have equaled the Cards’ streak of pitching excellence.1

Cardinals versus Phillies, September 13-15The first-place Cardinals held a half-game lead over the Phillies in the NL East as the two teams began a three-game series at Veterans Stadium on September 13. In the opener, Steve Carlton supplied all the run support he needed with a solo home run, earning his 20th win of the season as the Phils blanked the Cards, 2-0. With just three weeks remaining in the regular season, the Philadelphia had leapfrogged St. Louis atop the division.

The Cards and Phils played to the same final score the following night, but the outcome was reversed. Rookie John Stuper and All-Star fireman Bruce Sutter combined on a five-hit shutout. The key moment that night was Sutter’s eighth-inning strikeout of Mike Schmidt with the bases loaded. Darrell Porter’s two-run homer off Mike Krukow accounted for the only games’s only runs.

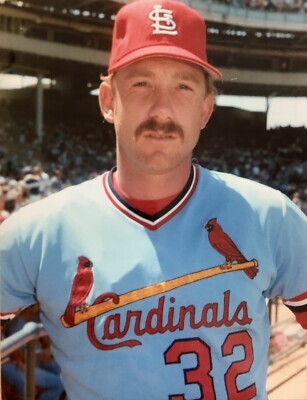

Rookie John Stuper won 12 games for the 1982 Cardinals.

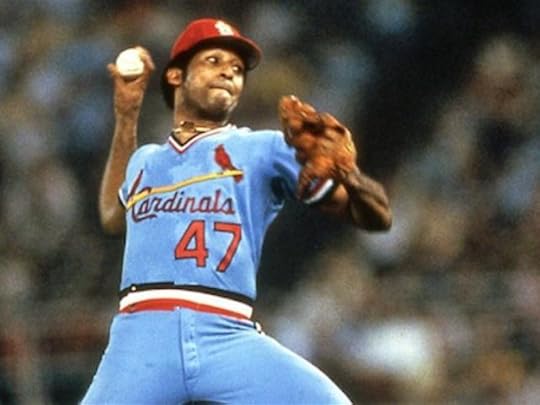

Rookie John Stuper won 12 games for the 1982 Cardinals.In the rubber game, Joaquín Andújar flummoxed the Phillies, tossing a complete-game three-hitter as the Cards rolled to a decisive 8-0 victory. The volatile righty improved his record to 13-10 while lowering his ERA to 2.54. St. Louis now led Philadelphia by a game and a half.

Cardinals versus Mets, September 17-19The Cardinals then made the short jaunt from Philadelphia to New York for a five-game set against the woeful Mets. Because of rainouts earlier in the season, the series included back-to-back doubleheaders. For those keeping score at home, that’s five games in three days! The gauntlet would test each team’s pitching mettle.

Cards starters Bob Forsch, Steve Mura, and John Stuper each won their respective starts, but the other two games had to be covered by the bullpen. No problem. Journeyman Eric Rasmussen threw seven innings of two-run ball, 43-year-old Jim Kaat tossed three frames as a de facto opener, and rookie Jeff Lahti pitched six stellar innings in relief. The Cards allowed only six runs in the series, winning all five contests. Just like that, the Cards had extended their division lead to four and a half games, their widest margin since early June.

Rookie Jeff Lahti tossed a career-high six innings of relief against the Mets. Cardinals versus Phillies, September 20-21

Rookie Jeff Lahti tossed a career-high six innings of relief against the Mets. Cardinals versus Phillies, September 20-21The wearied Cardinals returned home and began a two-gamer against the Phillies on September 20. St. Louis won the opener, defeating erstwhile Redbird John Denny. Andújar tossed his fifth shutout and ninth complete game on the season to earn the win. In the second game, Carlton—the eventual Cy Young Award winner—struck out 14 and yielded just two runs. Rasmussen, on the other hand, ceded five runs, four of which were unearned because of two errors. St. Louis lost the game, 5-2, but their streak of allowing two or fewer earned runs remained intact.

Joaquín Andújar was huge for the Cards down the stretch, going 5-0 with a 0.92 ERA in his last seven starts. Cardinals versus Pirates, September 22-23

Joaquín Andújar was huge for the Cards down the stretch, going 5-0 with a 0.92 ERA in his last seven starts. Cardinals versus Pirates, September 22-23On September 22, it was Dave LaPoint’s turn to get in on the action. Making his first start in 18 days, the southpaw limited the Pirates to one run in eight innings. Sutter pitched the ninth, nailing down his 35th save. “Someday, somebody’s going to wake up and see that we have some pitchers who know what to do,” said LaPoint after the game. “Maybe after the World Series, when we’re still sneaking up on people, maybe then they’ll notice us.”

The Cardinals’ pitching streak of allowing two earned runs or fewer had reached 11 games. It would not reach 12. The Bucs touched Forsch and the bullpen for five runs the following night. By then, however, the NL East was firmly in the Cards’ grasp. The team’s pitching staff, backed by a terrific defense, had carried the team when it mattered most. It allowed just 11 earned runs over 11 games, nine of which were victories. Although Whiteyball was centered around speed and defense, it turned out the ’82 Cardinals’ pitching wasn’t too shabby either. Yes, Dave LaPoint, we did notice.

Interested in reading about the Cardinals’ entire magical 1982 season? Check out my book, Runnin’ Redbirds, published in 2023 by McFarland Books.

The 2010 San Francisco Giants have the longest streak at 13 games. The 2022 Houston Astros, 1997 Los Angeles Dodgers, and 1991 New York Mets equaled the Cards’ streak of 11 games. ︎

︎The post The 1982 Cardinals’ Historic Pitching Streak appeared first on Eric Vickrey.

May 26, 2025

When the Mets Passed on Reggie Jackson

Heading into the 1966 June amateur draft, scouts and baseball executives all agreed that prep catcher Steve Chilcott and college outfielder Reggie Jackson were the two best players available. Every team had them ranked one-two on their draft list. Whitey Herzog later said that the 20 clubs were evenly split on which player was number one. Come draft day, however, only one team’s opinion mattered. By virtue of having baseball’s worst record a year earlier at 50-112, the New York Mets owned the first overall pick. The Kansas City Athletics picked second, poised to pounce on either Chilcott or Jackson, whichever was available.

Steve Chilcott: Can’t-Miss Prep CatcherAs a senior at Antelope Valley High School in Lancaster, California, in the spring of ’66, Chilcott hit .500 with 11 home runs in 25 games. After seeing him register hits in 15 of 16 at-bats, Mets scout Nelson Burbrink called Chilcott the best high school hitter he’d ever seen. Several Mets executives—including Bing Devine, Bob Scheffling, and Casey Stengel—went to see the phenom and came away equally impressed. Stengel was sold after watching Chilcott play just one game. “The boy has all the tools to become a major-league hitter,” he told the New York Daily News,

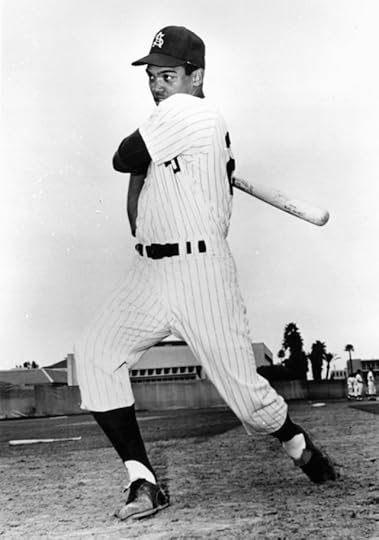

Steve Chilcott, shown here in his high school uniform, was considered a can’t miss prospect. Reggie Jackson: Sun Devil Slugger

Steve Chilcott, shown here in his high school uniform, was considered a can’t miss prospect. Reggie Jackson: Sun Devil SluggerJackson, three years old than the 17-year-old Chilcott, had just completed his sophomore year at Arizona State University, where he lettered in both baseball and football. The native Pennsylvanian hit .327 for the Sun Devils that spring, setting school records with 15 homers and 65 RBIs. “I couldn’t believe my eyes,” A’s farm director Eddie Robinson told Baseball America years later. “For the first time, I saw a prospect who rated plus in every category: arm, legs, glove, bat, and bat power.”

Reggie Jackson wowed scouts as a five-tool player at Arizona State.

Reggie Jackson wowed scouts as a five-tool player at Arizona State.Based on an organizational need at catcher and the strong opinion of Stengel, the Mets chose Chilcott. The A’s were ecstatic. Jackson, the top player on their list, landed in their lap with the second pick. Jackson signed for $80,000, the highest of any player that year. Chilcott received a $75,000 bonus from the Mets.

The Injury Bug BitesChilcott struggled mightily during his first year in pro ball, hitting .181 in 78 games between Single A, Rookie ball, and the Arizona fall league. He fared better to begin the ’67 season, hitting .290 with six home runs for the Single-A Winter Haven Mets through 79 games. But then the injuries began. He suffered a subluxation of his throwing shoulder on a head-first dive, causing him to miss remainder of the ’67 season and most of the next two because of recurrent dislocations. Chilcott returned to the field in ’70 following shoulder surgery but never regained full strength. A broken hand and busted kneecap further hampered his ability. The Mets traded him to the Yankees after the ’71 season. A year later, he was released, out of baseball at the age of 23.

A right shoulder injury ostensibly ended Steve Chilcott’s career. Reggie Jackson: Hall of Famer

A right shoulder injury ostensibly ended Steve Chilcott’s career. Reggie Jackson: Hall of FamerJackson, meanwhile, blasted 23 home runs in 68 minor-league games in ’66. He made his major-league debut exactly one year after he signed his pro contract. By the time Chilcott’s career had ended following the ’72 season, Jackson had already clubbed 157 round-trippers for the A’s, who were now in Oakland. He’d end his 21-year Hall-of-Fame career with 563 homers, five World Series rings, and 14 All-Star nods.

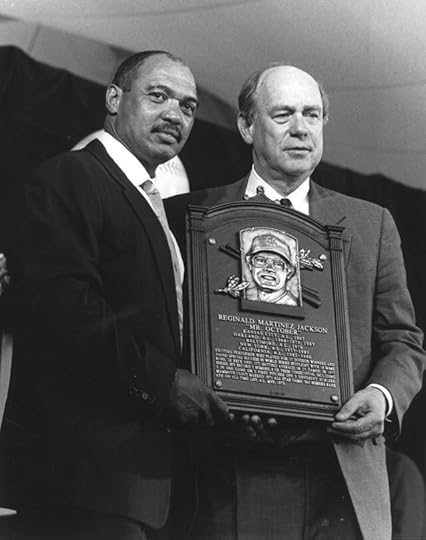

Reggie Jackson at his Hall of Fame induction in 1993.

Reggie Jackson at his Hall of Fame induction in 1993. Through the first quarter century of the amateur draft, Chilcott remained the only top overall pick who never reached the major leagues. (Brien Taylor, the Yankees’ first-round pick in 1991, was the next player to wear the dubious distinction.) Adding insult to injury, Jackson’s Oakland A’s defeated the Mets in the ’73 World Series. It was the Mets’ only postseason appearance in a decade of mediocrity. In hindsight, the Mets’ choice of Chilcott over Jackson remains one of the more regrettable decisions in franchise history.

For more about the 1996 draft, check out my post on the Dodgers’ class of ’66, a group that included Charlie Hough and Bill Russell.

For a look at the Mets’ worst trades in franchise history, check out this Bleacher Report piece from 2018.

The post When the Mets Passed on Reggie Jackson appeared first on Eric Vickrey.

May 21, 2025

Ray Lamb: The Last Dodger to Wear 42

Jackie Robinson’s 42 is unquestionably the most iconic jersey number in baseball history. It’s the only number retired across the Major League Baseball, an honor bestowed on Robinson a half century after he broke baseball’s color barrier. Now, every player in the league dons 42 on Jackie Robinson Day each April. The number became further cemented into the national lexicon in 2013 when Legendary Pictures produced a movie about Robinson’s life, a film simply titled 42. But remarkably, Robinson is not the last Dodger to wear the number. That distinction belongs to Ray Lamb.

Robinson became only the second Dodger to wear 42 when the team issued him the number in 1947. Pitcher George Jeffcoat wore it in his lone appearance for the ’39 club. After Robinson retired in December 1956, the Dodgers unofficially made his number off-limits to other players. The team officially retired it in 1972. But somehow, in 1969, 42 was issued to rookie pitcher Ray Lamb.

“The interesting part of the story is that Lamb joined the Dodgers on the road in St. Louis, where he made his major-league debut,” recalled Robert Schweppe, an associate of Peter O’Malley and writer at walteromalley.com. “For some reason the Dodger equipment manager (Nobe Kawano) had a number 42 in his extra jerseys. When Lamb came to the Dodgers, he was given number 42.”

Dodgers historian Mark Langill pointed out that the Dodgers were focused on establishing roots in Los Angeles, not on retiring numbers of former Brooklyn players—even legends like Robinson. “They didn’t bring that Brooklyn Bum character west with them, they weren’t about that,” Langill told the Los Angeles Times in 2019. “They were about establishing their own identity.”

Wearing 42, Lamb made 10 relief appearances for the Dodgers that August and September, registering an excellent 1.80 ERA across 15 innings. At the end of the season, Kawano realized his error and asked for the jersey back, telling Lamb that the team was eventually going to retire the number. “Did I have that good of a year?” quipped Lamb.

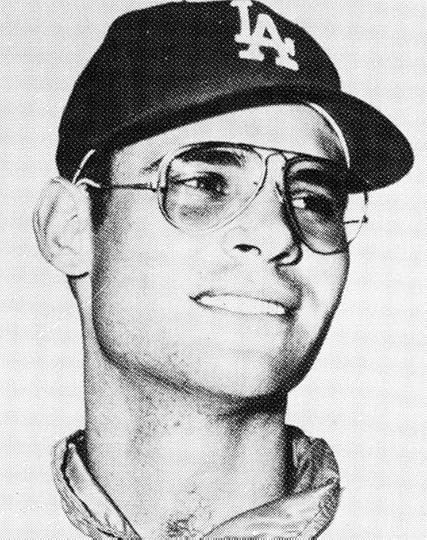

Ray Lamb played two seasons with the Dodgers.

Ray Lamb played two seasons with the Dodgers.The next season, Lamb switched to number 34. Ironically, that number, later worn by Fernando Valenzuela, will be retired in August 2025. Lamb posted a solid 6-1 record and 3.79 ERA out of the Dodgers bullpen in 1970. That winter, he and Alan Foster were traded to Cleveland for Duke Sims.

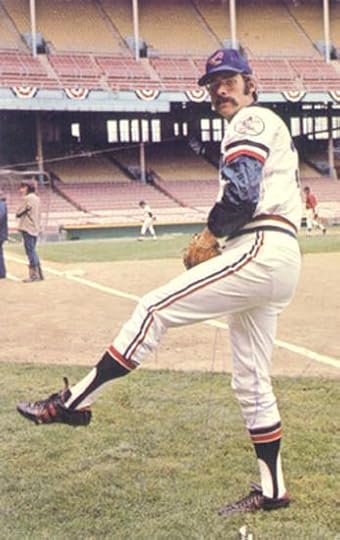

With the Indians, Lamb, a former 40th round pick in the 1966 amateur draft, wore number 30 and sported an epic glasses-mustache combination. During his five seasons in the majors, the USC product sported a 20-23 record and 3.54 ERA. Though his Dodgers tenure was brief, Lamb, who later became a successful commercial sculptor post-baseball, will forever hold a unique place in franchise history. “Jackie Robinson was such a great man,” said Lamb in 2019. “It is such an honor to be even remotely associated with him.”

Ray Lamb with the Cleveland Indians

Ray Lamb with the Cleveland IndiansThe post Ray Lamb: The Last Dodger to Wear 42 appeared first on Eric Vickrey.