Ugo Bardi's Blog

December 1, 2025

Harlequin Goes to War: The Slapstick Strategy

Young Alexander conquered India, Just he?

Caesar beat the Gauls. Didn’t he at least have a cook with him?

Philip of Spain wept when his Armada went down. Did no one else?

Bertolt Brecht, “In the City”

Years ago, I read a story about a magical African wooden mask that took over the minds of the people wearing it, turning them into murderers. The gist of the story was that, after several characters were killed, someone discovered that the mask was just a plastic toy made in Japan.

We are the mask we wear, and we all wear one. Good or bad, the mask is a quick way to define what kind of person we are. The very term “person” comes from the Latin word persona, which indicated the mask worn by actors on stage. It not only helped the public to identify the characters, but it also amplified their voice. It came from per sonare, to create sound. This is what we do on the stage of life. We are the sound we create.

Sometimes, there is truly nothing behind the mask, as in the Italian “Commedia dell’Arte,” the “Comedy of the Art,” popular during the 16th and 18th centuries. In these theatrical representations, masked actors played fixed roles, often improvising without a script. Harlequin (“Arlecchino”) is still widely recognizable today, with his motley costume made of irregular patches of cloth, playing the role of a light-hearted, nimble, and astute servant. We also remember Columbine, Pantaloon, Pierrot, and others. The Comedy was not different from our superhero stories, where characters are almost always masked and wearing a recognizable costume: Superman, Batman, Spiderman, and the others. Among other things, the Comedy gave us the concept of “slapstick,” a device consisting of two flexible pieces of wood joined together at one end. It could produce a loud noise when used to hit someone on stage, without causing any harm.

Masks are not used only for theatrical characters. States are disembodied creatures existing only because of the mask they show to the world. History books see them as creatures having a will of their own. We read, for instance, that “Austria attacked Serbia in 1914,” or “Germany attacked Russia in 1941,” as if they were comedy characters fighting each other. You can read a fascinating account of the personalized entities that clashed against each other during WWI in the “Ballet of the Nations” by Vernon Lee (1915).

Sometimes we tend to see the personality of states in the form of a single person, a homunculus that inflates to gigantic proportions to assume the form and the functions of a whole country. We say that “Napoleon attacked Russia” or "Putin invaded Ukraine.” Yet, this masked homunculus is a mere reflection of the larger mask that turns millions of different people, with different ideas, different goals, and different likes and dislikes, into a single egregore that moves onward, pushed by forces that nobody can control.

This idea of states as masks has led to terrible disasters throughout history. Lev Tolstoy wondered how it was possible that during the invasion of Russia in 1812, “Millions of men set out to inflict on one another untold evils – deception, treachery, robbery, forgery, counterfeiting, theft, arson and murder – on a scale unheard of in the annals of law-courts down the centuries and all over the world.” Yet, that happened because they identified themselves with a specific mask in the form of one or another state, France, Russia, or others.

It is no less dangerous today, when the personification of states is common in political and strategic discussions. Let me give you an example taken from the site War on the Rocks. At a cursory glance, just from the title, you would think that this site is a jok, with its claim of “National security. For insiders. By insiders.” and “Join War on the Rocks and gain access to content trusted by policymakers, military leaders, and strategic thinkers worldwide.” But if you listen to what our leaders say in public, you’ll see that this style of thinking and speaking informs the discussion.

Let’s quote from an article by Nick Damby, published on October 2, 2025, on the War on the Rocks site.

“America faces three adversaries: Iran, the persistent destabilizer, determined to develop nuclear weapons; Russia, the acute threat, invading Ukraine and threatening NATO; and China, the pacing challenge, attempting to topple America’s international leadership.”

This sentence reads like the blurb for a superhero adventure movie. The masked characters are all in place. The hero, America, faces three bad guys, Iran, Russia, and China, each with specific evil goals.

So, how would Mr. Damby advise the hero to perform his quest? Here it is how (he considers that Iran has already been defeated):

How do you deter and, if necessary, defeat China and Russia simultaneously without exhausting your nation’s resources, power, and attention? You don’t. Instead, you sequence the threats.

This guy is a genius. If you can’t fight your enemies together, you fight them separately, one by one. How was it that nobody had thought of that? Of course, the enemies would need to collaborate, patiently waiting for their turn to be defeated. But that’s a minor problem, don’t you think so?

And then:

Sequencing logic demands weakening one remaining competitor before risking an unwinnable two-front war. But which competitor? Russia is the obvious choice. Moscow is weaker and moved first by invading Ukraine; it should be punished first.

Mr Damby seems to think that he is a God, or at least God’s envoy, to suggest how punishments should be meted out. Then, after having punished Russia,

… America may finally concentrate its resources and attention on countering its great rival this century: China.

You would think it is all a joke, a fantasy, a historical fiction plot, but it is not. Or, at least, plenty of people take this approach seriously, as you can note in many public statements on these matters. And you can learn from history how leaders tend to reason in this way.

Ask why Napoleon decided to invade Russia, and you’ll see that kind of reasoning at work. His advisor, Armand de Caulaincourt, reports that Napoleon told him: ‘In less than two months I shall be in Moscow, in three months I shall have peace, and in two years I shall be master of the world!’ (Mémoires du général de Caulaincourt, duc de Vicence). In other reports, we note that Napoleon was impatient to “finish the business” with Russia, afraid that the Russians would ally with Sweden and Britain. So, he was playing the sequencing game. Too bad that the Russians didn’t cooperate.

As things stand, it seems that we are masked characters in a comedy being played on the world’s stage. We don’t know the plot, nor how the comedy will end, and not even whether it will turn into a tragedy. What we know is that the actors are not armed just with harmless slapsticks.

____________________________________________________________________________

November 28, 2025

Are we on the Edge of Collapse? Impressive Data from a Recalibration of World3

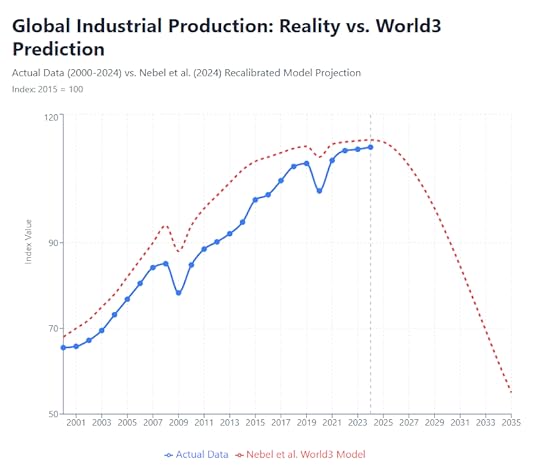

One more Seneca Cliff coming soon? If so, we are in for a rough fall. Graph prepared by Claude on the basis of the data by Nebel et al.

I always say that models are not predictions; they are qualitative illustrations of what the future could be. But as the future gets closer to the present, models can start being seen as predictive tools. It is the weather/climate dichotomy, so aptly exploited to confuse matters by politically minded people in the discussion about climate. Right now, we are getting close to the point that we could forecast a collapse in the same way as we can forecast the trajectory of a tropical storm.

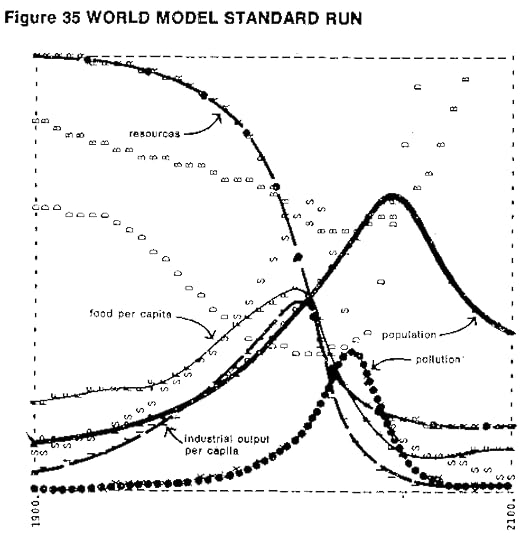

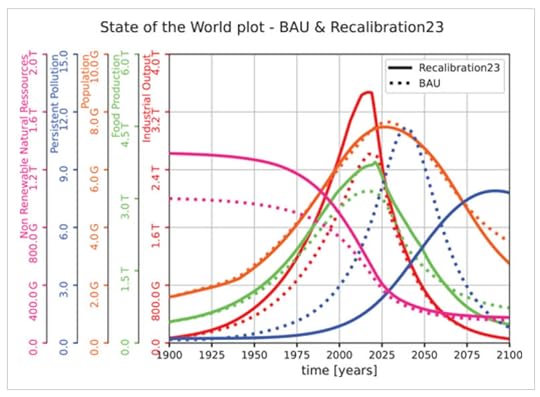

So, you remember how “The Limits to Growth” generated a long term forecast in 1972. Here it is

The start of the collapse of the industrial production (here calculated in per capita terms) was supposed to be at some moment between 2010-2020. A little too early, because we passed that moment. But that calculation was made more than 50 years ago, and you it is legitimate to think that it needs some readjustments. That was what Nebel et al did in a recent paper; they recalibrated the same model (word3) on the basis of the available real-world data. And here is their result.

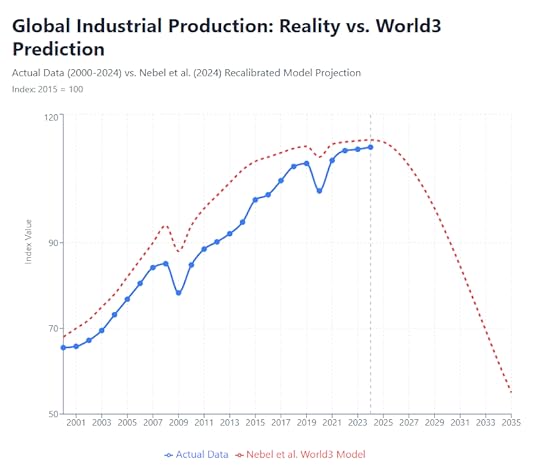

Note the red curve, industrial production. Are we facing the abyss? At first, it looks unlikely, but I compared Nebel’s data with the real-world ones for industrial production, and I had Claude plot them together. The result is shown at the beginning of this post; let me reproduce it here again:

Do pay attention to the other curves of Nebel et al.’s paper. Agricultural collapse will be at about the same time as the industrial one. Population should start collapsing a few years later. Pollution will reach a peak around 2080 at levels some three times higher than the current ones. If this is a good prediction, we are in for a rough ride, a VERY rough ride.

But never forget: even hurricanes may change their trajectory at the last moment, and there are reasons for optimism. Listen to Sabine Hossenfelder, for instance. I think that before making this clip, she smoked something really strong. But who knows? She might be right.

November 23, 2025

Global Dumbing: The Consequences

Don’t you have a feeling that certain fictional things are becoming true?

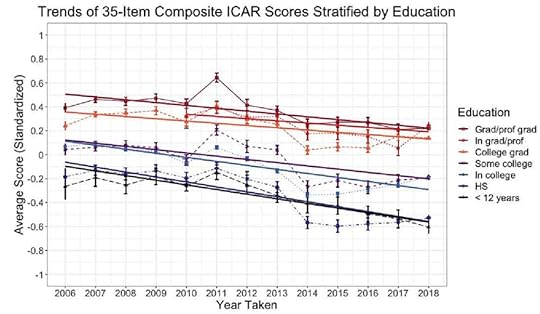

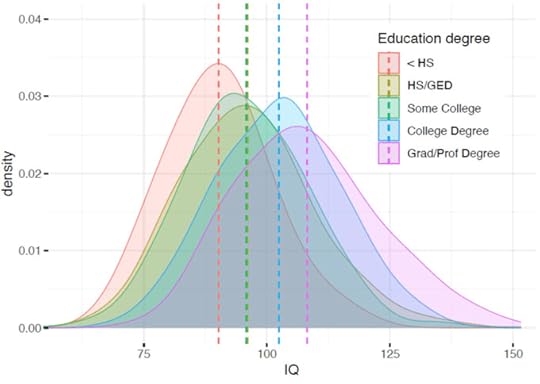

You may have heard of “global dumbing.” It is the idea that Intelligence Quotient (IQ) scores are declining everywhere in the world. Is it a real phenomenon? Probably yes, although the trend is weak. You can find some data in this 2018 article. Here are data for US adults

As you see, we are dealing with fractions of an IQ point compared with an average score of about 100. But the trend is there: intelligence in the US seems to have peaked in 2011 and then started a slow decline. It fits with the qualitative feeling you can have by watching TV or reading the debate (to call it in this way) on social media.

Recently, I proposed that global dumbing may be correlated to the increasing concentration of CO2 in the atmosphere, which acts as a metabolic poison on the human brain. It does not need to be the sole explanation. The decline may be due to other pollutants (heavy metals or microplastics), to electromagnetic fields, or non-chemical factors, such as exposure to dumbing media in TV and the Web.

The story is complex it involves understanding the effect of pollutants on the human brain. Let me just assume that global dumbing and it is gradually getting worse. Let me also assume that IQ tests do measure something (*see note at the end of this post) even though that may not be what intelligence truly is. Then, what do we expect to happen?

To frame the question, let me show you this graph (h/t Chuck Pezeshsky).

This figure gives you some idea of how IQs are distributed among various fractions of the US population — likely, the situation is not very different in other Western countries. Note how the IQ of people with PhD/graduate degrees is shifted by about 10 points toward higher intelligence, as you would expect. Conversely, people without a schooling degree lean on the other side of the distribution, with an average around 90, although quite a few of them have IQs higher than the average.

That fits with the way our society is structured. Most tasks that people normally perform in their jobs involve nothing more than moving things from one place to another. These things may be physical entities (say, you are a mailman or a truck driver), or numbers/strings of letters (say, you are a clerk, or a government bureaucrat). Or, maybe, your job is to try to move a chunk of lead from the inside of a gun barrel into someone’s body, but it is basically the same idea. Human brains have a certain capability to evaluate the position of things in space and to act on them. And that’s what they are used for.

Now, assume that global dumbing affects everyone in the same way, and that we are discussing a loss of a few IQ points, say, 5 points. Then, the whole set of curves would shift to the left. Would that change something in our society? Probably not. Surely, there would be fewer geniuses around, but geniuses are neither appreciated nor encouraged in our society, and, in most cases, they are not needed. Consider theoretical physicists: they are an elite of super-smart scientists. Most of them are engaged in arcane tasks such as making models of dark matter or cosmic strings. Their work is totally irrelevant to the world as it is now, even assuming that the things they are studying actually exist. And even if they were to be useful for something, probably a sufficient number of high-IQ people could be found to work on them even in a moderately dumbed-down world. Let’s say that global dumbing would solve for academia the problem that Peter Turchin calls “Elite overproduction.”

For the rest of the IQ distribution, a shift to the left of 5 points is unlikely to change much in ordinary people’s jobs. If you are a clerk or an employee in a fast food joint, you don’t need intelligence beyond the ability to recognize icons on a screen. The same is true for all those jobs termed “clerical” — you have to follow protocols, but little more. So, in principle, the world could remain the same. Bureaucrats would still harass ordinary people, trucks would still carry food and merchandise, supermarkets would sell groceries, and people would go to work every morning and take a vacation once in a while.

One political consequence of the general dumbing down would be that most people would lose their ability to critically evaluate what they are told. They would become even easier to fool for government propaganda and all the various private and public scams that pervade our world. Smart politicians would get to the top by feeding the dumbed-down population with lies and aggressive statements, convincing them to vote for people who promise to beggar them. Nothing surprising: we are already seeing that. It would just get worse (it is).

We could also imagine a really large IQ drop, say 20-30 points. If it does occur, that would make a big difference, and quite possibly wreak or society. One consequence would be that a large fraction of people, probably a majority, would lose the capability to read and write, which is already being gradually lost in Western countries. It is true that most people don’t really need to be able to read and write for their everyday jobs (**), but at least some do. If something breaks down, there has to be an instruction manual somewhere. But if there are not enough people able to read and understand an instruction manual, then it is a disaster. Everything collapses. Maybe bots will come to the rescue?

An alternative scenario is that the social structure collapses in the near future because of external factors, mineral depletion, pollution, global warming, or a nuclear war. Then, what would happen to dumb people? To survive societal collapse, you don’t need to be highly intelligent, but you have to be adaptable and socially collaborative. In terms of survival, I see a hard time for bloggers and social media stars, just as for string theorists, but some chances for people who can make things with their hands and who can maintain a social circle in the real world. If humankind survives, in time, it may recover the IQ points lost in our era, provided that the new generations of human beings are not exposed to daily doses of TikTok.

_______________________________________________________________________

_______________________________________________________________________

* Note. The question of the relevance of IQ tests is important. One thing that they do NOT measure is the capability of adaptation in difficult times. They have been developed in modern times by Western people and tested on Western people, so it is not surprising that when they are used on non-Western people, the result is low IQs, even if the tests are modified and supposedly “tailored” for non-Western cultures. This is a long story; let me just tell you that I have direct experience with the Romani culture (the “gypsies”), people who notoriously score low in IQ tests. In my experience, though, the Romani people are smart, reactive, and extremely adaptable, masters of managing social interactions. I gave lectures to the young ones in an educational program, and it was a pleasant experience to speak to people who reacted critically and intelligently to what I was telling them. Nothing like the sullen attitude of my regular Italian students. Whether the Roma could be good scientists, I don’t know. Surely they are not common nowadays. But maybe we need creative and adaptable people much more than we need scientists.

** Note 2. Most of the Romani people I know are illiterate or semi-literate. In my opinion, that doesn’t hamper their capability to communicate, socialize, know things, and build things. Their view of the world, though, is substantially different from that of literate people, as we are. We are always conscious of the records of the past, and we always try to extrapolate these records into the future. The illiterate Romani people, for what I can say, live in a perpetual present. As some people said, they have perfected the art of forgetting and of living happily in the present moment. They never heard of the Stoic Emperor Marcus Aurelius, but they would agree with him when he said, “It doesn’t matter whether your life is long or short. The only life you have is the moment in which you live.”

November 21, 2025

Civilization Collapse: A Seneca Cliff Ahead?

This interview was created by Vesna de Vinča, a journalist, writer, and producer from Belgrade. It was part of the World Conference on Science and Art for Sustainability held in Belgrade in October 2025 organized, among others, by Nebojsa Neskovic.

Ugo Bardi - National Interuniversity Consortium of Materials Science and Technology, University of Florence, Italy; The Club of Rome (CoR); World Academy of Art and Science (WAAS)

1. The Seneca Effect and the Global System

Questions: In your interpretation of the Seneca Effect, you show that civilizations do not disappear gradually – they collapse suddenly, as if their internal axis of energy and purpose has been exhausted. Do you believe that our global system has already entered this silent process of self-destruction? And in your view, can the Seneca Effect be applied to the current situation in the USА and Western world politics, with the rapid and unexpected changes occurring there right now? Could this sudden collapse lead us to the Third World War and shared global ruin? Or is there still the possibility of an internal rebirth – a transformation that comes not from technology, but from a shift in consciousness?

Answers: The Seneca Effect applied to societal collapses is so common in history that it is remarkable how leaders and rulers go down the cliff while swearing that their kingdom will never fall. The Western Roman Empire went down to the dustbin of history while emperors were still convinced that ‘’Rome is Eternal’‘. And there are many more recent examples: think of the Soviet Union! So, it is reasonable to say that the modern American Empire will not be an exception. Indeed, we can see some evident signs of impending collapse in the Western system: internal struggles, power grabs, economic decline, including one of the most typical symptoms: the militarization of society. That doesn’t mean the collapse will start immediately, just that it is moving in that direction.

About wars and global ruin, societal collapses often involve internal conflicts, which may be intense and destructive. But collapse usually removes the capability of a society to engage in military expansion, so a third world war can only happen while the system is still relatively healthy. If it doesn’t happen in the near future, we may never enter WW III. About a rebirth, it is not just possible: it is a feature of collapses. It is a feature of the universe that involves getting rid of the old and the unsustainable to create the new and the better adapted. It happened with the Roman Empire, which eliminated the old and parasitic imperial structure and generated the sophisticated and beautiful civilization we call the ‘’Middle Ages. It will happen for us, too. However, we can’t say yet what will come after us.

2. Science, Technology, and the Illusion of Salvation

Questions: Humanity believes that science and Artificial Intelligence will save us from the limits it has imposed on itself. Can technology – which created this hyper-complex world – really be a path toward balance? Or is, as you often suggest, the real challenge to relearn how to live in accordance with the laws of nature – simpler, humbler, and wiser?

Answers: Technologies are not instruments to create balance; they tend to do the opposite. The present predicament of our society, its ’hyper-complexity is the result of the fossil fuel technologies introduced during the past few centuries. That source of energy is now winding down because of the double challenge of depletion and pollution. It remains to be seen what kind of flow new technologies will be able to provide, while at the same time generating little pollution. A post-fossil society may be much different from the one we live in right now; rather, it may have points of contact with the European Middle Ages. Our society is ugly, wasteful, and materialistic. The Middle Ages were elegant, efficient, and spiritually oriented. The future may be similar, provided we can maintain a certain degree of energy supply to the societal structure. No energy, no society.

3. A New Narrative for Human Civilization

Questions: If, as Seneca says, “everything grows slowly, but decays quickly,” perhaps the only choice we have is to find out how to live between those two moments. In your opinion, what could be the new narrative for humanity – one in which growth is no longer a measure of power, but a measure of consciousness? And what role do art, philosophy, and what we call spiritual maturity play in this transition?

Answers: The Romans reacted to the perception of the decline of their society by developing the philosophical school called ‘’Stoicism’‘. It was a view of life that took into account how fleeting human life is. It was Emperor Marcus Verus Aurelius, also a Stoic, who lived about one century after Seneca, who noted that it doesn’t count whether one lives a long life or a short one. What one owns is only the fleeting moment of ‘’now,” which must be used to live as a human being is supposed to live: according to duty and responsibility. Later, Christianity added charity as a virtue and Islam codified it as a duty. God is said to be benevolent and merciful, and we can try to imitate Him the best we can in that fleeting moment we call “life.”

4. Truths and Misconceptions about CO2 – between Science and Dogma

Questions: In today’s public discourse, CO2 has almost become a mythological symbol – for some, a ‘’poison that destroys the planet, and for others, an innocent molecule unfairly demonized. You point out that the truth is much more complex: CO2 affects not only the climate, but also the metabolism of the biosphere and even human cognitive abilities. How can we distinguish scientific truth from ideological dogma amid such conflicting narratives? And do you believe that, in this whole climate story, it might be even more important to understand the internal biological and psychological effects of CO2 on life, rather than only its external impact on the planet’s temperature?

Answers: I do believe that some important effects of CO2 have been neglected in the debate on climate change. In particular, its direct poisoning effects on living beings and their environments have been completely missed. These effects might do more damage to us and to the whole ecosystem than the temperature rise caused by the warming effect of CO2. But that’s nothing more than a confirmation that Earth’s ecosystem, the entity in which we live and that makes us live, is one of those systems that we call ‘’complex’‘. That has a specific meaning: it doesn’t just mean it is complicated; no, it means that it reacts to perturbations in ways that are difficult or impossible to predict before they happen – typically by collapsing: think of a house of cards. That’s one of the features of the Seneca Effect: it occurs only in complex systems, and its sudden effects are often caused by small perturbations whose effect was impossible to predict. So, the current ongoing collapse has multiple causes, both physical and social. We will go through it in order to find a new social, technological, and human equilibrium. But it doesn’t have to be sudden and brutal. There is no hurry to collapse! We have to go with the flow. If we do, everything will be well.

h/t Vesna de Vinča, shown below

November 17, 2025

From Shanghai with Energy

The Shanghai Skyline. If you emerge out of the city center to gaze on that, you have the definite impression that you just stepped out of Elon Musk’s spaceship that landed on another planet.

Back home after 10 days in China, I am slowly recovering from the effects of the jet lag and I can start putting some order in my impressions from what I saw and experienced.

First of all, the meeting: it had an ambitious title, “Earth-Humanity Reconciliation.” It was a rather large-scale event organized, among others, by UNESCO, the Club of Rome, and the Shanghai University of Engineering Science. It was a marathon of presentations among researchers from 15 different countries and I did my best to absorb as much as I could.

The meeting reinforced my impression that the Chinese are serious about the energy transition. They adopted the concept of “Ecological Civilization,” 生态文明 (shēngtài wénmíng), which is now an official government policy, enshrined in the Chinese constitution. The idea is that Nature and the human economy must be in harmony with each other, a concept also expressed as “The Two Mountains.”

Just talk? I would say no. When the Chinese set their minds to doing something, they usually do it, and they do it seriously. It’s not that there is no greenwashing in China, but the Chinese have understood one thing: if they don’t quickly free themselves from fossil fuels, they will not be able to maintain the prosperity they have built through decades of hard work and sacrifice.

China imports almost all the oil and gas it uses, which is expensive and makes the country strategically vulnerable. They still use coal, which remains the main source of electricity for now (60% of the total power production, against about 40% from renewables), but it is highly polluting and can’t last forever. The conference discussed how to achieve “Net Zero” emissions; the current government plan is to get there by 2060. It may be too late to avoid major damage, but the Chinese are known for exceeding expectations when they put their minds to it. In this, they are being helped by the population having stopped growing, and starting now a slow decline. It will reduce the pressure on resources and generate less pollution.

China’s success in renewable energy has been nothing short of astonishing. The Chinese industry is now capable of producing photovoltaic systems at costs so low that they beat all other sources, except perhaps wind. Not to mention new, low-cost batteries, electric cars, automation, robots, and the electrification of the economic system in general. These are all areas where China is gaining a technological advantage over the West that could soon become impossible to bridge. And the point is not so much that they are moving faster than us (intended as “the West”). The point is that while they are moving forward, we are moving backward. Instead of investing in the future, we are struggling to focus on obsolete technologies. What to say? We will get what we deserve.

Thus, the growth of renewable energy production in China is exponential, while coal production is stalling and is expected to decline in the coming years. The results are clear to see. Chinese cities were once known for being horribly polluted, but today, if you walk along the busy boulevards of Shanghai, you can smell the aromatic plants growing at the sides (apart from where the main smell is that of Chinese restaurants!). And the only noise you hear is the buzz of electric motors. The scooters are all electric. Most private cars are electric, while heavy traffic is not yet electrified, but they are working on it.

So, should we learn from China how to solve our current impasse? I think so, and you may be interested in a recent book by Chandran Nair and others, Understanding China. Below, Nair is shown here while giving a talk at the Shanghai meeting.

In this and in other books, Nair exposes the concept of the “strong state,” which I discussed in a previous post. I wrote that, “In his book The Sustainable State (2018). Chandran Nair forcefully makes the point that no serious measures can be taken against threats such as pollution or climate change if the state is not strong. That does not mean a dictatorship: it means a state that enjoys citizens’ trust, supports itself on a fair taxation system, and can clamp down on the attempts of the lobbies to carve the nation’s wealth among themselves.”

Is it a good recipe to adopt for the West? That’s difficult to say, and the fact that the Chinese system has been so successful up to now doesn’t mean it will easily adaptable to the West. Nor it is evident that the Chinese system will be able to face the challenges awaiting humankind in the near future: mineral depletion, pollution, and climate change. But one thing is sure: the Chinese are doing something good and we have a lot to learn from them.

___________________________________________________________

To finish, here, the concept of “ecological civilization” is illustrated by the goddess Gaia, together with her Chinese colleague, the Goddess Guanyin.

November 14, 2025

Jerusalem: the Center of the World?

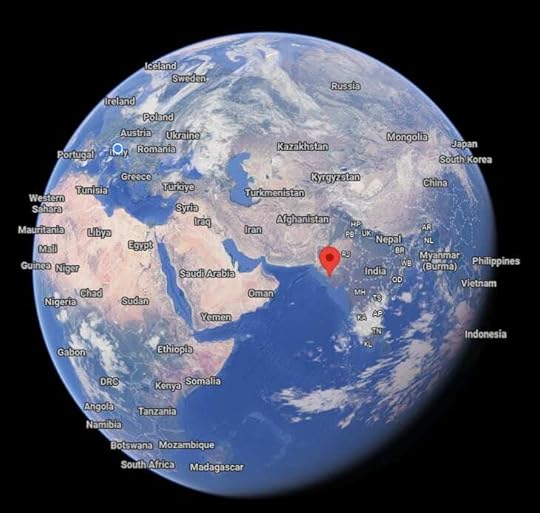

The Bünting cloverleaf map, created in 1581 by the German Protestant pastor and theologian Heinrich Bünting. Drawing from Medieval traditions, it placed Jerusalem at the center of the world. But is it, really?

Reposted from “Chimeras” 10 Oct 2025

By Ugo Bardi

In Medieval Europe, Jerusalem was considered to be the center of the world. It was probably the result of a line by Ezekiel 5:5: “This is Jerusalem; I have set her in the center of the nations, with countries all around her.” And that was taken seriously. Not only Jerusalem was considered at the actual center of the world, but it stood just above Hell, while the Garden of Even was a real place, located just nearby, near the opening of the Gihon Spring. This spring, which is today a mere trickle compared to what it once was, originates just outside of what is now the Old City of Jerusalem.

You can see below a map of the world that’s much older than Bünting’s cloverleaf. It is more difficult to read, but you can note Jerusalem exactly at the center. It is the “Psalter World Map” found in a psalter. It was created during the 13th century.

But where is the real center of the world? And how should we define it? In physics, you have the concept of “center of mass,” the average position of the mass distribution in an object or system. You can also use the term “centroid” for the average position of all the points of a system. For a physical object, it is the balance point if the shape were made of a thin, uniform sheet of material, where it would balance perfectly on a pin.

You can easily define the centroid for the land mass of Earth. For instance, the centroid of the Afro-Eurasian block is located somewhere in Iran. If you want to know precisely, it is at 34.4° N, 58.6° E. Here is the Afro-Eurasian centroid point, shown in Google Maps, not terribly far from Jerusalem, but not close, either.

The closest city to the centroid is Gonabad, a place that you have probably never heard of, but, curiously, it turned out to be a place I had some affinity with. It is there that the last king of the Sasanian empire, Yazdegerd III, took refuge before being killed, it is said, by a miller. His death signaled the collapse of the Sasanian Empire. If you are interested in Iranian history, you can see an eerie and fascinating movie on Yazdegerd (or Yazdigerd) III at this link.

If we consider all the continents, including Antarctica, the point moves to somewhere in Sudan, but that’s not so interesting. A purely geographic average doesn’t tell us what the real “center of the world” is. It should be, rather, based on the distribution of people over the continents.

If we look for the “people’s centroid” of the Afro-Eurasian bloc, the result is different. I asked Grok-4 to do the calculation, and here are the results.

Now, the distribution is dominated by the huge population of India and East/South East Asia. The result is that the centroid moves to the Western coast of India. Here are the coordinates: 23°15’36.0”N 69°40’48.0”E. I didn’t check Grok’s calculation, but it seems to be a reasonable result. The centroid location is heavily influenced by the large populations of India and Southeast Asia.

The population centroid is in the Indian state of Gujarat, of which I must confess, I only vaguely knew the existence. The closest city is Bhuij, which I had never known to exist. Anyway, it is in the Gujarat state. According to Wikipedia:

Kutch (Kachchh) was ruled by the Nāga chieftains in the past. Sagai, a queen of Sheshapattana, who was married to King Bheria Kumar, rose up against Bhujanga, the last chieftain of Naga. After the battle, Bheria was defeated and Queen Sagai committed sati. The hill where they lived later came to be known as Bhujia Hill and the town at the foothill as Bhuj. Bhujang was later worshiped by the people as snake god, Bhujanga, and a temple was constructed to revere him.

Which, I’d say, sounds like a fitting legend for a place that turns out to be the center of the Afro-Eurasian bloc.

What kind of place is that? Well, the Google mobile didn’t exactly reach the population centroid, although it could get within just a few tens of meters from it, as you see here.

That’s what you can see from the closest place where the Googlemobile arrived, about 30 m away.

This is the center of the world. Honestly, the area doesn’t look very impressive in architectural terms, but I suppose the people who live there see it as their sweet home.

I’ve never been to Gujarat, but from what I could see from Google Maps, Bhuj looks not unlike other places I saw in India, around New Delhi. Dogs, cows, small shops, and the ubiquitous tuc-tucs moving around.

I wonder what it would be to enter one of those small shops, buy a Coke or something like that, and ask, “Do you people know you are at the population centroid of the Afro-Eurasian bloc?” Who knows? They could answer, “Yes, we know. We read it in the blog of a weird Italian guy.”

November 9, 2025

Science and the Dragon

The Goddess Gaia and a Dragon discuss science together.

Here is a paper that my coworkers and I published in “Organisms” a few years ago. Appearing in an academic journal, it was not visible to the general public, but I think it was interesting enough to be republished on “The Seneca Effect” blog. It was written before the AI revolution that promises to create some order in the accumulation of scientific knowledge but that, so far, has failed to do so.

(note, some typos in the original paper were corrected in the version published here)

Organisms: Special Issue: Where is Science Going?

Vol. 5, No. 2 (2022)

ISSN: 2532-5876

Open access journal licensed under CC-BY DOI: 10.13133/2532-5876/17628

Ugo Bardi, Ilaria Perissi, Luisella Chiavenuto & Alessandro Lavacchi

a Dipartimento di Chimica ‘Ugo Schiff’, Università di Firenze, Florence, Italy - bGlobal Sustainability Institute, Anglia Ruskin University, Cambridge, United Kingdom- cIndependent Researcher, Aosta, Italy - dIstituto di Chimica dei Composti Organo Metallici del Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche (ICCOM-CNR), Area della Ricerca di Firenze, Sesto Fiorentino, Italy

*Corresponding author: Ugo Bardi, Email: ugo.bardi@unifi.it

Abstract

We start from an analogy: science can be seen as one of the dragons of Western mythology, described as sitting on their hoard of gold but not using it for any useful purpose. Similarly, scientists seem to be content with accumulating knowledge, doing little or nothing to use it outside their restricted domain of expertise. We argue that this attitude is one of the elements causing the ongoing decline of science as a way to produce innovative knowledge. We propose that the situation could be improved by encouraging scientific communication and the redistribution of the scientific treasure of knowledge in the form of “mind-sized” memes.

Keywords: knowledge distribution, memes, specialization, h-index

Citation: Bardi, U 2022, “Science and the Dragon: Redistributing the Treasure of Knowledge”, Organisms: Journal of Biological Sciences, vol. 5, no. 2. DOI: 10.13133/2532-5876/17628

Introduction

There are several reasons for the evident decline of science: unreliability, falsifications, cronyism, elitism, politicization, hyper-specialization, aversion to innovation, and more. This decline is not just reducing the capability of science to produce culture and innovation. It is also generating a serious disconnection of science from society as a whole. Non-scientists are developing an ideological aversion toward the dominating “technoscience,” seen as representing the entire scientific process.

In part, these problems can be attributed to a few (or maybe not so few) bad apples in the basket. But there is one profound problem affecting the whole scientific enterprise: science has grown so much that by now it produces an unmanageable mass of data and results which are incomprehensible except to people working in the narrowly specialized fields in which the results were produced.

We could compare science to the dragon Fafnir of Norse mythology or to one of its modern versions, such as Smaug of Tolkien’s novel The Hobbit. Dragons are said to sit on immense hoards of gold that they do not use and that nobody else can use. Science seems to be doing the same with the knowledge it creates, a treasure kept hidden in the darkness of scientific journals, inaccessible and incomprehensible to the majority of people and to most scientists as well. It has been said that a typical condition of scientists is to know more and more about less and less. If the trend continues, eventually they will know everything about nothing. Indeed, the dragon is not just sitting on the treasure of knowledge, but it is dominating its way of production by means of controlling science funding as well as the career of scientists. Science is becoming more and more like a dragon locked in its giant cave.

A recent paper by Chu and Evans (2021) offers a dramatic illustration of the current impasse of science. These authors found that the larger a specific research field is, the more unequal the impact of a scientific article becomes in terms of the number of citations. In other words, in science there holds the rule that “the rich becomes richer,” just as it happens in the financial world (this is also called the “Matthew Effect” from the parable of the talents in Matthew’s gospel). The result is that new entries in the field do not succeed in removing obsolete research from the top places of interest, if they ever manage to see the light on a scientific journal. The Matthew effect takes place with grant applications. Those scientists who can accumulate research grants in an early stage of their career tend to keep being successful (Bol et al. 2018). Also, this effect discourages innovative new entries in research.

In this paper, we examine the question and propose a tool inspired by Seymour Papert’s book Mindstorms (Papert, 1980). According to Papert, the learning process for humans is based on unpacking complex concepts into easily understandable sub-units that he calls “mind-size” (or “mind-sized”) bites. The author proposed this idea mainly in the framework of teaching geometry to children (Abelson et al. 1974). However, its value applies also to adults (Maedi 2013).

We propose here to enlarge Papert’s concept of “mind-size learning” to match the current scientific enterprise. We do not aim at renouncing specialized knowledge, but valuing the transmission of ideas using a language that is mutually understandable by scientists working in different fields and, at the same time, not just by scientists but also by practitioners of humanities and by the public. In other words, we propose to redistribute the dragon’s gold to the people.

Creativity and Knowledge

Mainly, we owe the concept that creativity is an emergent property of knowledge to Jean Piaget (Maedi 2013; Gruber & Vonèche 1977), who expressed it in the sentence “creativity is knowledge.” There follows that if we want to restart the progress of science, we need “cross-fertilization” from one scientific field to the other, including humanities. This idea is also known as “interdisciplinarity,” a concept that is often praised but rarely practiced.

Several factors tend to discourage interdisciplinarity in modern science. One is the attempt to classify scientific research in specific sectors. Hence, research is forced inside sealed compartments that discourage exchanges of ideas between different fields. Another factor is the use of various “indices” developed with the purpose of measuring productivity and the competence of an individual scientist or of an academic journal. These indices assume that competency is proportional to the number of papers that a scientist produces (“publish or perish”), taking also into account the number of citations received. In general, a paper will most likely be published if it deals with well-known ideas and concepts. Also, people who work in the same field as the author will cite it more than others. This encourages scientists to remain within the limits of their fields in order to maximize the number of their publications and the number of citations (Migheli & Ramello 2021). Venturing outside one’s area of specialization and producing actually innovative research would mean stepping into the darkness where a scientist’s work is likely to be ignored. No citations, no career—no career, no scientist. Indeed, it would be useless to blame bureaucrats for having developed indices that, in large part, are well integrated with the way scientists behave and the way the scientific process is performed. The problem lies deep in science.

The lack of interdisciplinarity in science is not just a matter of quality, as we can measure it. (Chu & Evans 2021) report that “Examining 1.8 billion citations among 90 million papers across 241 subjects, we find that a deluge of papers does not lead to turnover of central ideas in a field, but rather to ossification of canon. (…) A novel idea that does not fit within extant schemas will be less likely to be published, read, or cited.”

Chu and Evans propose that this phenomenon is due to the large number of papers published in every field, which makes it impossible for researchers to keep abreast with the general work. We also need to take into account a parallel phenomenon that Chu and Evans do not mention: as a certain field becomes larger, it also becomes more fragmented. That is, a large field spawns smaller subfields, which in turn will spawn smaller fields. The set of scientific fields is fractal.

The Web of Science database includes 241 subjects of study. Such a classification is arbitrary. For instance, Wikipedia lists 1475 fields. Even the finer Wikipedia subdivision is rather “macro” in comparison to the way certain fields are perceived by their practitioners. Note also that the fractalization of science does not take place just across different fields: it also takes place at the temporal level. The basic concepts of single disciplines can be progressively forgotten not because they have been invalidated, but simply because they suffer a sort of de-facto obsolescence that condemns them to oblivion. This phenomenon was clearly seen during the past two years of the epidemics that saw the rediscovery and sometimes the rejection of some basics of medicine that somehow had been forgotten. Just as an example, a recent review (Ashby & Best 2021) reports how “misconceptions about herd immunity and its implications for disease control are surprisingly common.” This loss of scientific memory is the local version of the wider dissociation occurring between scientific and humanistic disciplines, which gradually lose their common roots until they become completely alien to each other.

The result is that whenever scientists from two separate fields happen to discuss the same subject, they tend to behave like enemy ships exchanging broadsides against each other before vanishing in the fog. There have been several examples of this aggressive behavior. One is that of the study The Limits to Growth (Meadows et al. 1972). The study originated from the field of engineering control systems, but its method was applied to describing the global economic system. As a result, it didn’t fit with the methods used in the field of economics. As argued in the book The Limits to Growth Revisited (Bardi 2011), the debate occurred among people who did not understand each other. Hence, the study was demonized based on an insufficient debate and little evidence. Another example is the remarkable scientific quarrel between physicists and geologists about the cause of the “Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event, ‘’ some 66 million years ago. In 1980, a group of researchers, most of them physicists, proposed that the impact of an asteroid had caused the extinction (Alvarez et al. 1980). Geologists, instead, mostly attributed the event to a large-scale volcanic eruption (Bond & Wignall 2014). The row that followed is by now legendary and the two groups involved had difficulties in understanding each other (Alvarez 1988).

These examples show how different scientific fields can differ in views, methods, and terminology. They become ossified, with scientists belonging to different subfields unable, and often uninterested, to speak to each other. A blatant example of such a fractalization and hyper-specialization of science may be the recent Covid-19 crisis, with the birth of a hierarchical view of human health that saw one specific ailment as separated and more important than all the others. The emergence of the pandemic led to a rush to publish that created a large number of poor quality papers—a rush described as a “carnage” (Bramstedt 2020). Kendrick (2021) reported a similar outcome when statins became a popular subject of research in the 1990s: other fields involving the prevention of cardiovascular disease were practically abandoned.

These phenomena are the cause of a chain of troubles and incomprehension transmitted from one scientific field to another. This generates diffidence and mistrust not just within science, as it is understood nowadays, but also among people working in the humanities, and the public. If the sad state of science is not recognized, we will continue financing and producing poor science, useful to nobody.

Science as Language: Mind-size Concepts

Nowadays, a great number of different people speak international languages, such as English. The result is that widely spoken languages tend to incorporate new terms from other cultures (e.g., pizza from Italian, ubuntu from Bantu, perlage from French, and many others). The increase in the size of the vocabulary generates, probably as a compensation, a reduction of its grammatical and syntactic complexity (Reali et al. 2018).

These trends are typical of ordinary languages but can also be seen in science. The huge number of terms developed in different fields generates a simplification in the grammatical structure of the scientific language. Scientific papers are written in a standardized form of English that avoids clichés like the plague. Such a language tends to be simple, especially when used by non-native speakers, who are now probably the majority of the active scientists in the world. There have been proposals for the use of a codified and simplified form of English, for instance, the ASD-STE100 Simplified Technical English (STE).

However, the grammatical simplification of scientific English does not solve the problem of the proliferation of concepts. This is a gigantic problem: the human mind has limits. So, how to make a mass of concepts available outside the specific fields that produced them? Here, we can take inspiration from the work of Seymour Papert, who proposed the concept of “mind-size” (or “mind-sized”) models (Papert 1980).

Papert’s idea is in itself “mind-sized.” It implies breaking down complex ideas into sub-units that can be easily digested, just the way we do when we take bites from a too-big chunk of food. In approaching a field of science, we try to break it down into mind-size bites that represent the essence of the story.

In fields other than hard sciences, this method is known as “slogans,” which are the political equivalent of mind-size concepts. As an example, the first volume of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital is 1134 pages long. Nevertheless, many people defined themselves as Communists without having read Marx’s text, just on the basis of slogans. For instance, “Soviet power plus electrification” was proposed as a synthetic definition of Communism by Vladimir Illich Lenin (Lenin 1919), and that seems to have been sufficient for many people.

Can we do something similar with science? Answering this question can only be made in qualitative terms. So we now present a number of case studies to illustrate how it is possible to communicate complex scientific ideas in the form of mind-size bites.

Case Studies

Darwin’s Natural Selection

Darwin’s book, The Origin of Species (1859), is a series of mind-size concepts. It contains some tables and some calculations, but not a single equation (and note that he uses the term “plot” only with the meaning of a parcel of land). The book is easily understandable by people not trained in biology or even in science. Yet, it was a milestone in understanding not just the behavior of Earth’s biosphere, but the more general concept of “complex systems.”

Darwin’s ideas are easy to condense into mind-sized statements. A classic one is “The survival of the fittest:” a synthetic interpretation of the mechanism of evolution. This is not the only possible way to express Darwin’s ideas in a single sentence. Another one is “Nature in red tooth and claw,” a poetic interpretation written by Tennyson (actually before the publication of Darwin’s book). Another somewhat poetic interpretation is The blind watchmaker, the title of a book by Richard Dawkins (1986).

These mind-size explanations are not necessarily excessive simplifications and can also illustrate different interpretations of the theory. For instance, “The survival of the fittest” is not equivalent to “Evolution by natural selection.” The second statement may imply that evolution maintains the stability of the genetic endowment of a species without individuals striving to become “better.” The latter interpretation seems to be more popular nowadays (Gorshkov et al. 2004).

A good example of how a mind-size interpretation of Darwin’s theory can be profitably used in real life is about a well-known problem in medicine: that of the growing antibiotic resistance of bacterial pathogens (Aslam et al. 2018). There is no need to be an expert in molecular biology or genetics to understand the problem: when bacteria are attacked using antibiotics, natural selection will favor forms that are resistant to the attack. These will rapidly become the major component of the bacterial population. The new variants may be highly dangerous, not because natural selection favors more lethal species–the opposite is actually true–but because the task of fighting the infection has been entrusted to the antibiotic, preventing the immune system from developing appropriate defenses. If the antibiotic fails to provide protection, then the body has no defense to fight the new infection. This general problem affects all medical factors. If a vaccine is not 100% effective in eradicating a virus, then it may favor the development of new, vaccine-resistant viral variants.

These concepts have been known for a long time, nevertheless, antibiotics have been used freely and in large amounts, not just to cure human illnesses, but as a preventive measure to keep farmed animals healthy, with the result that antibiotics have been spreading along the food chain, affecting the whole ecosystem (Kumar et al. 2020). Not only has it been impossible to control the growth of antibiotic production up to now, but the industry gleefully forecasts a 300% increase in sales for 2027 (Data Bridge Market Research 2020).

One of the reasons for the antibiotic spread is that the public and most physicians do not understand that natural selection is more than just a theory mentioned in textbooks, but a reality of everyday life. Among others, Andersson et al. (2020) made this point recently. If people knew the basic concepts of evolutionary biology, then the current problem could have been at least mitigated.

Mind-size Dynamic Models

The recent pandemic has put to severe strain the capabilities of the world’s governments to manage it. Their reaction highlighted how little of the basic elements of the epidemic cycles were known by decision-makers and by their advisors alike. Some scientists have been maintaining that the growth of the epidemic was expected to be “exponential,” extrapolating it to absurdly high levels. Even specialists in epidemiology were often unable to provide sound advice, mainly owing to the failure of complex, multi-parameter models that consistently overestimated the diffusion of the Covid-19 epidemic (Saltelli et al. 2020). This was the result of a phenomenon known as “creeping overparametrization,” the tendency of modelers to tinker with the model by adding “ad hoc” parameters.

This is a widespread issue of modeling complex systems. Models are not prophecies; they are computing machines designed to explore the “cause and effect” space. The result is that less detailed models can often provide better long-term forecasts than complex ones. For instance, the “base case” model of the 1972 study The Limits to Growth, one of the first “integrated assessment models” in the history of modeling, has described reasonably well the trajectory of the principal parameters of the human economy over 50 years (Bardi 2011; Turner 2008; Herrington 2021). Note that the model used in The Limits to Growth was relatively “mind size” because it was based on just five principal stocks and their simple interactions.

Even simpler models provided reasonably good results. Bardi and Lavacchi (2009), as well as Perissi and colleagues (2017), experimented with system dynamics-generated “mind size” models and found that their results are comparable with those of more complex models. In fact, even simpler models were useful as descriptors of future events. For instance, Marion King Hubbert (1956) described the production peak of crude oil in the United States with a simple model involving only two parameters. In general, all these models provide similar results in terms of “bell-shaped curves,” which can describe apparently different phenomena such as epidemic cycles (Kermack et al. 1927), oil extraction (Bardi & Lavacchi 2009), and fisheries (Perissi & Bardi 2021).

Figure 1: The Hubbert peak: a “mind size” result of dynamical models of complex systems.

Network Analysis

Many modern models are based on the concept of “network”. A network can be defined as a graphical representation of either symmetric or asymmetric relations between discrete objects/individuals. The objects are called nodes or vertices, and usually represented as points. We refer to the connections between the nodes as edges, and usually draw them as lines between points.

This kind of approach can lead to a clear mind-size representation of the diffusion of an epidemic: each node in the network represents a person. The edges between nodes represent social connections over which a disease can be transmitted (Dottori & Fabricius 2015) Ashby & Best 2021). In itself, the network representation does not generate a mind-size model of how the infection grows and then declines in time. Nevertheless, the mathematical implementation of the model can take into account the probability of infection spread through the neighbors of an infected node and of the recovery of already infected people. The resulting cycle is the same “bell-shaped” curve described in the previous section, as shown in Figure 1.

Networks can represent all sorts of systems in the real world. For example, one could describe the Internet as a network whose nodes are computers or other devices and whose edges are physical (including wireless) connections between the devices. The World Wide Web is a huge network where pages are the nodes and links are the edges. Other examples include social networks of acquaintances or other types of interactions, networks of publications linked by citations, and transportation, metabolic, and communication networks.

At the basis of a network analysis (Barnes & Harary 1983), graphs are an intuitive way of representing and visualizing the relationships between many objects even more than stock and flows. The dedicated branch of discrete mathematics called graph theory provides the formal basis for network analysis, across domains. It represents a common language for describing the structure of all those phenomena that can be modelled by networks.

However, as previously commented for the case study in 3.2, a large and complex modelling network requires a huge number of differential equations to describe the system. This is the case of large genetic networks (Bornholdt 2005). In fact, extrapolating the standard differential equations model of a single gene (with its several kinetic parameters) to large systems would render the model prohibitively complicated. One possible way to simplify such models would be to find a “coarse-grained” level of description for genetic networks. This means focusing on the system behavior of the network while neglecting molecular details wherever possible.

The Schrödinger equation

The Schrödinger equation describes a variety of phenomena involving quantum particles. This deceptively simple equation, in most cases, turns out to be impossible to solve, except in terms of approximations. In chemistry, it can describe the distribution of the electric charge around atomic nuclei and in complex molecules. The procedure to determine this distribution is as far as it can be from a “mind-size” concept, and the same is true in terms of understanding the results. Nevertheless, over the years, chemists have developed graphical concepts to help non-specialists understand the electron distribution around nuclei. These graphical objects are called atomic or molecular “orbitals,” a term that derives from the old interpretation of electrons “orbiting” around the nucleus. Although you need a certain level of training in chemistry to use orbitals as mental tools, they mercifully spare us from the details of the underlying quantum physics.

A solution of Schrödinger’s equation for one of the possible states of an electron associated with a hydrogen nucleus is given in Figure 3 as a “mind size” representation. These representations make sense for chemists, who use them to grasp some of the chemical

Figure 3: Calculated 3d orbital of an electron’s eigenstate in the Coulomb-field of a hydrogen nucleus. https:// e n.w ikiquote .org /w iki/Atomic_orbital#/me d ia/ File:Hydrogen_eigenstate_n3_l2_m0.png. CC BY-SA 3.0.

properties of atoms and molecules without the need of being experts in quantum mechanics. For instance, usually the interpretation of the aromatic properties of some organic molecules is understood in terms of these graphical representations of the electronic distribution.

Conclusion: How to Improve Communication in Science?

The global number of published scientific reports was estimated at ca. 50 million in 2010 (Jinha 2010). At a rate of 2-3 million papers published every year, nowadays this number may be closer to 100 million. Assuming that an article has an average length of 5 pages, we have a corpus of knowledge spanning some 500 million pages, with good possibilities of reaching one billion pages in the near future. The Bible, with about 1400 pages in its English version, is a leaflet in comparison.

What is the value of this giant mass of data? On this, we may cite Henry Poincaré, who said, “Science is built up of facts, as a house is built of stones. But an accumulation of facts is no more a science than a heap of stones is a house” (Poincaré, 1905). Of course, databases index scientific publications, but that does not necessarily create knowledge, just like a list of the shape and weight of each stone in the heap does not create a house.

Science is, after all, a human enterprise, and it has to be understood in human terms, otherwise, it becomes a baroque accumulation of decorative items, just like gold in the paws of a dragon. The accumulated knowledge of science must be somehow made “alive” if it has to generate further knowledge.

This is the key insight that Papert generated in 1980 in terms of “mind size models.” In order to be alive, science must have a comprehensible form. That does not mean renouncing the conventional accumulation of data and results in the form of specialized papers. It means that scientists should feel their duty to express results in the form of mind-size bites, understandable by their colleagues and, as much as possible, by the public. Scientific production and communication cannot be seen as separate tasks: they are one and the same thing. Of course, this idea will not make any inroads in science if it is not supported in some way, for instance by specific legislation aimed at redefining the parameters that control scientists’ careers and their salaries, especially avoiding the deadly trap of the “h-index.” But, more than legislation, perhaps what is needed is just a different attitude. Among other things, we need to reconcile modern “science” and humanism, as it used to be not long ago. We need to stop thinking that there exist “two cultures,” in the view of Charles Snow (1959). There is only one culture: the human culture, in the sense that ancient philosophers, such as Plato, had clear.

A return of “science” from the realm of the dragons’ caves for both scientists and the public to appreciate it is possible. The job of the dragonslayer is a little out of fashion nowadays, but it could still be useful (Heinlein 1961).

References

Abelson, H, Goodman, N & Rudolph, L 1974, Logo Manual. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Artificial Intelligence Laboratory, LOGO Memo, No. 7.

Alvarez, L 1988, “Opinion. The bricks of scholarship”, The New York Times, Jan 21, p. 26.

Alvarez, LW, Alvarez, W, Asaro, F & Michel, HV 1980, “Extraterrestrial cause for the Cretaceous-tertiary extinction”, Science, vol. 208, pp. 1095–1108.

Andersson, DI et al. 2020, “Antibiotic resistance: turning evolutionary principles into clinical reality”, FEMS Microbiol. Rev., vol. 44, pp. 171–188. https://doi. org/10.1093/femsre/fuaa001

Ashby, B & Best, A 2021, “Herd immunity”, Curr. Biol., vol. 31, R174–R177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.01... Aslam, B, et al. 2018, “Antibiotic resistance: a rundown of a global crisis”, Infect. Drug Resist., vol. 11, pp. 1645 1658. https://doi.org/10.2147/IDR.S173867

Bardi, U 2011, The limits to growth revisited, New York: Springer.

Bardi, U & Lavacchi, A 2009, “A simple interpretation of Hubbert’s model of resource exploitation”, Energies, vol. 2, pp. 646–661. https://doi.org/10.3390/en20300646

Barnes, JA & Harary, F 1983, “Graph theory in network analysis”, Soc. Netw., vol. 5, pp. 235–244. https://doi. org/10.1016/0378-8733(83)90026-6

Bol, T, Vaan, M de & Rijt, A van de 2018, “The Matthew effect in science funding”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 115, pp. 4887–4890. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1719557115

Bond, D & Wignall, P 2014. “Large igneous provinces and mass extinctions: an update”, Geol. Soc. Am., vol. 505, pp. 29–55. https://doi.org/10.1130/2014.2505(02)

Bornholdt, S 2005, “Less is more in modeling large genetic networks”, Science, vol. 310, pp. 449–451. https://doi. org/10.1126/science.1119959

Bramstedt, KA 2020, “The carnage of substandard research during the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for quality”, J. Med. Ethics, vol. 46, pp. 803–807. https://doi.org/10.1136/ medethics-2020-106494

Chu, JSG & Evans, JA 2021, “Slowed canonical progress in large fields of science”, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., vol. 118. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2021636118

Data Bridge Market Research 2020, “Antibiotics market: global industry trends and forecast to 2027” [Online]. Retrieved from:

https://www.databridgemarketresearch.... reports/global-antibiotics-market (accessed 10.17.21).

Dottori, M & Fabricius, G 2015, “SIR model on a dynamical network and the endemic state of an infectious disease”, Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, vol. 434, pp. 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. physa.2015.04.007

Gorshkov, VG, Makarieva, AM & Gorshkov, VV 2004, “Revising the fundamentals of ecological knowledge: the biota–environment interaction”, Ecol. Complex., vol. 1, pp. 17–36.

Gruber, H & Vonèche, J 1977, The essential Piaget: An interpretive reference and guide, New York: Basic Books. Heinlein, RA 1961, Stranger in a strange land, New York: Putnam Publishing Group.

Herrington, G 2021, “Update to limits to growth: comparing the World3 model with empirical data”, J. Ind. Ecol., vol. 25, pp. 614–626. https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13084

Hubbert, MK 1956, “Nuclear energy and the fossil fuels”, in: Spring meeting of the Southern district, American Petroleum Institute, Plaza Hotel, San Antonio, Texas, March 7–8-9,. San Antonio.

Jinha, A 2010, “Article 50 million: an estimate of the number of scholarly articles in existence”, Learn. Publ., vol. 23, pp. 258–263. https://doi.org/10.1087/20100308

Kendrick, M 2022, The clot thickens: The enduring mystery of heart disease, Cwmbran: Columbus Publishing Limited. Kermack, WO, McKendrick, AG & Walker, GT 1927, “A contribution to the mathematical theory of epidemics”,

Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. Contain. Pap. Math. Phys. Character 115, pp. 700–721. https://doi.org/10.1098/ rspa.1927.0118

Kumar, SB, Arnipalli, SR & Ziouzenkova, O 2020, “Antibiotics in food chain: the consequences for antibiotic resistance”, Antibiotics, vol. 9, no. 10, p. 688. https://doi.org/10.3390/ antibiotics9100688

Latour, B 1993, We have never been modern, trans. C Porter, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Lenin, VI 1919, “The economic basis of the withering away of the state”, in: The state and revolution.

Maedi, S 2013, “Piaget’s theory in the development of creative thinking”, Res. Math. Educ., no. 17. https://doi. org/10.7468/jksmed.2013.17.4.291

Meadows, D, Meadows, DH, Randers, J & Behrens, W, Jr 1972. The limits to growth, New York: Universe Books.

Migheli, M & Ramello, GB 2021, “The unbearable lightness of scientometric indices”, Managerial and Decision Economics, vol. 42, no. 8, pp. 1933–1944.https://doi. org/10.1002/mde.34861944MIGHELIANDRAMELLO

Papert, S 1980, Mindstorms: computers, children, and powerful ideas, New York: Basic Books.

Perissi, I & Bardi, U 2021, The empty sea: The future of the blue economy, Springer International Publishing. https:// doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-51898-1

Perissi, I, Bardi, U, Asmar, T & Lavacchi, A 2017, “Dynamic patterns of overexploitation in fisheries”, Ecol. Model., vol.

359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2... Poincaré, H 1905, Science and hypothesis, Walter Scott Publ.

Reali, F, Chater, N & Christiansen, MH 2018, “Simpler grammar, larger vocabulary: How population size affects language”, Proc. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci., vol. 285: 20172586. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2586

Saltelli, A et al. 2020, “Five ways to ensure that models serve society: a manifesto”, Nature, vol. 582, pp. 482–484. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-01...

Snow, CP 1959, The two cultures, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Turner, G 2008, “A comparison of The limits to growth with 30 years of reality”. Glob. Environ. Change, vol. 18, pp. 397–

411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2... Serres, M 1968, Hermes ou la communication, Paris: Minuit. Serres, M 1982b, The parasite, trans. L Schehr, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Serres, M & Latour, B 1995, Conversations on science, culture and time, trans. R Lapidus, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

November 5, 2025

A Voice Crying in the Desert: Ignoring the Poisoning Effect of CO2

The Goddess Gaia knows that CO2 is a poison, but her human children refuse to believe that.

Guest Post by Olle Hollertz, retired psychiatrist, Oskarshamn, Sweden libbershult@icloud.com

Sometimes I wonder if our desire not to deviate from the norm or the dominant view of the group is a motivation that trumps logic, reason and truth. In some situations this attitude can become unsustainable, especially in connection with crises and disasters, but without external pressure, a majority chooses to align itself with the ranks and sometimes not even then. Convincing reasoning and obvious facts will not be able to change dysfunctional beliefs and outdated conclusions, both in the humanities and the natural sciences, not before the existing system has completely cracked. Changes are difficult and scary, shaking up habitual patterns and therefore triggering various defense mechanisms to maintain the existing.

In those individuals who have seen through this and value truth and reason more than the confirmation of the group/society, it leads to frustration and resignation, and sometimes even to exclusion. It is no gift to be able to draw out the consequences of what is happening today and see what awaits in 5-10 years. Almost always it leads to a feeling of being “a voice crying in the desert”. It is equally painful to intellectually realize that truth, reason and compassion do not even affect people in one’s vicinity and even more so cannot affect the primitive, almost archaic, drives that seem to govern society.

The white haired independent scientists described by Ugo Bardi in one of his posts is an excellent example of a voice crying in the desert. I am sure that many experienced, independent scientists have many experiences, thoughts and hypothesis, which I think someone ought to be interested in. From my own life and work I have some examples of hypothesis, I think are worth to study. One is the connection between hypermobility in joints/skin/connective tissue and adhd, other are lithium as a medication against dementia, animals as therapists, paleoendocrinology and the counterproductive effects of dopamine, AI’s relation to the unknown unknowns and the danger of being locked in a paradigm and of course how to adapt society to Gaia.

Another example is Ugo Bardi’s research about increasing CO2 levels and the possibility that it explains the Reverse Flynn Effect, the decline in intelligence levels observed worldwide, which I find very interesting. I attach here a short comment about CO2 and anxiety. It’s all about balance, homeostasis and equilibrium. Not too much, not too little, in Swedish defined by the word “lagom”, or as the Greeks carved on the temple in Delphi, “Meden agan”.

It is well known that too little CO2 in the blood, due to hyperventilation, creates feelings of panic and anxiety. When stressed or panicked, we tend to hyperventilate and then the CO2 levels in the blood are ventilated down and this reinforces the feelings of panic. A well-tried way to deal with this condition is to breathe into a bag, which normalizes the CO2 levels and relieves the feelings of panic, which I have my own experience with. This is not to say that higher CO2 levels can act as an anti-anxiety agent, but just an example of how important balance is.

In the past, we had rituals that helped us change, transform ourselves mentally in order to meet new challenges and deal with the unknown. My fear today, when rituals have lost their transformative power and AI helps us avoid being confronted with the unknown, is that we have ended up in a mental prison, a so-called paradigm, which is almost impossible to break out of. AI’s rapid access to superhuman amounts of information and human inherent laziness contribute to this. At the same time, there are individuals who sense that there are other alternatives, who are uncomfortable, drawn to confrontation and want to break free, but these individuals are ignored, met with silence or openly opposed. They feel like the crying voice in the desert. The driving force of the majority, who may indeed disagree among themselves, is that the hegemony of the group, regardless of whether it is local or global, must not be threatened. The majority or those in power, regardless of whether it is a dictatorship or a democracy, today also have increasingly greater opportunities for control, surveillance, sophisticated repression, propaganda and often a large capital of violence.

Isaac Asimov had the ability to foresee this political and mental situation and his solution was the second hidden foundation. On the edge of the galaxy, there was the first foundation, which acted openly and opposed the central power. When civilization was threatened with destruction, the task of the second foundation was to preserve, in the hidden and undercover, knowledge, skills, and insights, which are necessary building blocks for a civilization. It is the same challenge that we face today and Ugo Bardi describes in his text about white haired, independent, often retired scientists. Now it is a matter of linking them together in virtual networks and, with the help of AI, preparing the next mental leap into the “unknown unknown”. The German/American philospher Eric Voegelin pays great attention to these leaps of consciousness, “Leaps of Being”, when he explores what the Greeks called Metaxy, or “In Between”.

______________________________________________________

Today I read an article about the same problem from Cambridge Press about how to promote quality before quantity. This inspired me to compare how Einstein and Wittgenstein earned their doctorate.

Merits sufficient for Ludwig Wittgenstein’s doctorate:

Submission of the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus as a thesis.

A short formal defense with Russell and Moore.

No further research, coursework, or thesis was required.

To obtain his doctorate, Einstein needed to:

Submit a thesis that was reviewed by his supervisor Alfred Kleiner.

Defend the work orally before the faculty.

Pay the administrative fee (which he actually forgot at first!).

Publish the thesis in a scientific journal – which he did later that year (1905) in the Annalen der Physik.

Einstein earned his doctorate through scientific method and empirical testing; Wittgenstein earned his through philosophical originality and intellectual authority. Einstein fulfilled the demands of the system – Wittgenstein made the system bow to him. Despite the differences, I think both, during periods of their lives were voices crying in the desert.

Olle Hollertz, retired psychiatrist, Oskarshamn, Sweden

libbershult@icloud.com

November 2, 2025

From the Chinese Mountains

No long post for this week. I am in Shanghai for a meeting. The Chinese are taking seriously the concept of the “two mountains “ (you see the characters in quotes behind me.) A simple concept that focuses on harmony between the two “mountains”, nature and human actions. A typical Chinese approach that avoids the trap in which Westerners fell: nothing intermediate between hard catastrophism and rapacious capitalism.

Back to blogging soon!

October 30, 2025

Testosterone Collapse: One more Seneca Cliff

A guest post by Lukas Fierz, who discusses the decline in human testosterone and correlates it to other problems caused on the human reproductive capability by chemical pollution. He concludes that we face a “reproductive Seneca Cliff.” Humans may not be able to reproduce themselves anymore before the end of the 21st century. He says, “This is a progressive chemical castration. Being a severe bodily harm, it should be prosecuted ex officio. But, surprisingly, there is not even a public outcry, probably because the media steadfastly refuse to publish anything about it.”

A Guest Post by Lukas Fierz, M.D.

Decreasing sperm counts will interfere with human reproduction starting from the middle of our century. The decrease is worldwide and has accelerated to over two percent per year, as shown in 200+ studies on 50’000+ men. The total loss since 1950 exceeds 50 percent.

Male testosterone also declines by one percent per year according to seven out of eight long-term studies from Europe, Israel, Brazil, and the US. Several non-systematic studies confirm a downward trend: e.g., 40 percent loss during 30 years in the American Midwest.

Testosterone decline must be similarly widespread as sperm decline and probably also accelerating because both share common causes: Pesticides and phthalates (the plasticizers we get from food packages and cosmetics) affect not only sperm but also testosterone by disturbing testicular development in the male embryo. Moreover, any decline in testosterone diminishes sperm production. E.g., one kilogram of extra weight costs a man one percent of his testosterone (and one year of remaining potency) and thereby also decreases his sperm count.

After removal of one testicle (hemicastration), the other one takes over and sperm and testosterone return to normal within months. Therefore, the observed 50 percent reduction amounts to much more than a hemicastration. It brings some men already into female territory.