“The King of Frauds” and investigative journalism

I want to thank University of Maryland Professor Mark Feldstein for inviting me to speak to his investigative journalism seminar at the Merrill School of Journalism earlier this week about the story that broke open the Credit Mobilier scandal. It was an honor and pleasure to speak to idealistic aspiring journalists and a chance to reflect on an early example of investigative reporting.

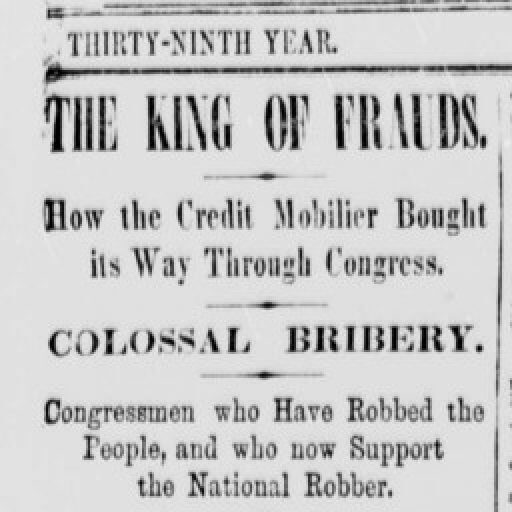

The story of the Credit Mobilier scandal begins on September 4, 1872, when the four-page New York Sun filled its entire front page, and several columns on two inside pages, with a blockbuster exclusive that dominated the headlines for months and reverberated politically for years. Under the headline “The King of Frauds,” the feisty New York daily detailed the operations of Credit Mobilier of America, the lucrative construction arm of the transcontinental Union Pacific railroad, and how its investors sought influence in Congress.

The headlines atop the Sept. 4, 1872 story in the New York Sun that broke the Credit Mobilier scandal wide open.

The headlines atop the Sept. 4, 1872 story in the New York Sun that broke the Credit Mobilier scandal wide open.The scoop, unearthed by Sun Washington correspondent Albert M. Gibson, opened with inflammatory headlines that promised revelations of “colossal bribery” and “congressmen who have robbed the people, and who now support the national robber.” Several introductory paragraphs followed in a similar vein. The story promised to reveal “the most damaging exhibition of official and private villainy and corruption ever laid bare to the gaze of the world.”

Although the scoop appeared without a byline, Gibson lapsed into the first person to describe his disgust with what he discovered. “If there was room for a doubt in this case, I for one would be in favor of giving these men the benefit of it, for it is almost beyond belief that our public men could have fallen so low. But there is no escaping the conclusion that they are guilty.”1

Those were different times.

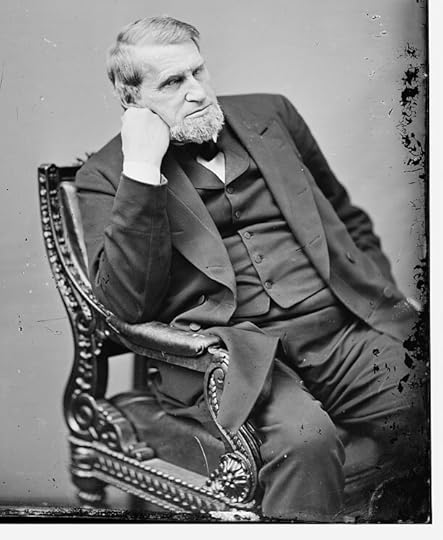

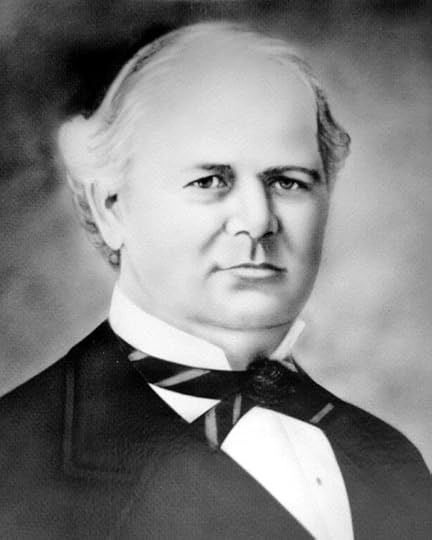

The rest of the story consisted of transcribed deposition testimony from a lawsuit filed against Credit Mobilier by railroad speculator Henry Simpson McComb. Its most explosive revelation was the publication of letters written by Representative Oakes Ames of Massachusetts, one of the Union Pacific’s biggest stockholders and a Credit Mobilier investor.

The letters were written to McComb, who had been pestering Ames for additional Credit Mobilier shares after the company divided unissued stock among its leading investors, many of whom also held stock in the Union Pacific. Ames declined to provide McComb with any of the extra Credit Mobilier shares and explained why.

The unclaimed stock had been distributed on Capitol Hill, according to Ames, with the intent with creating a congressional cadre motivated to support the Union Pacific’s interests on Capitol Hill.

“We want more friends in this Congress,” Ames wrote in one of his letters to McComb, “& if a man will look into the law (& it is difficult to get them to do so unless they have an interest to do so), he cannot help being convinced that we should not be interfered with.”2

Rep. Oakes Ames, R-Mass. Library of Congress.

Rep. Oakes Ames, R-Mass. Library of Congress.In a subhead at the top of the story, the Sun printed a list of members of Congress alleged to have received Credit Mobilier shares from Ames. The list included:

— Vice President Schuyler Colfax, who bought shares while House Speaker;

— James G. Blaine, who succeeded Colfax as Speaker;

— Senator Henry Wilson of Massachusetts, who would succeed Colfax as Grant’s vice president;

— James A. Garfield, a rising Republican star in the House who would be elected president in 1880; and

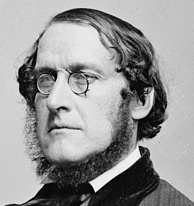

— Democrat James Brooks of New York, the sole member of his party implicated in the scandal.

Modern journalists would find the story extremely odd. The headlines were comically sensational. The Sun made no attempt to reach any of the congressmen named for comment. Paragraph after paragraph described in excruciating detail the financial machinations of Credit Mobilier and the Union Pacific. The story’s most explosive material – the letters written by Ames – appeared at the very end.

In addition, there was much that was wrong with the Sun’s expose. Many of the lawmakers it listed – including Blaine — did not obtain Credit Mobilier shares. The paper charged that members received between 2,000 and 3,000 shares apiece when in fact most received 30 and only one – Brooks – received as many as 150.

Mistakes such as these enabled partisan Republican newspapers to dismiss the story out of hand. The New York Times characterized it as a “stupid falsehood” published by a despicable scandal sheet. “The charge originally appeared in the Sun,” the Times sniffed, “which is prima facie evidence that it is a lie.” The New York Tribune, whose editor Horace Greeley was running a quixotic long-shot campaign for president against Ulysses S. Grant, reluctantly printed a condensed version of the story on an inside page. Even so, the Tribune was closer to the mark than the Times when it predicted that the “public will look with deep interest at further developments in the case.”3

Henry Simpson McComb. Library of Congress.

Henry Simpson McComb. Library of Congress.The Tribune proved correct. The story would not die. It tapped into growing animosity directed at the railroad industry, whose corrupt influences in state legislatures and abusive pricing practices enraged government reformers and farmers from Maine to California. At the same time, the story confirmed what members of Congress and some in the press already knew or suspected about the extent of Credit Mobilier’s influence in Congress.

In March 1868, more than four years before the Sun published its story, Republican Representative Cadwallader C. Washburn of Wisconsin delivered a long speech on the House floor in which he flayed Credit Mobilier as a cabal of investors who were fleecing the Union Pacific by overcharging for construction work.

Four months later, the managing editor of the New York Tribune alerted Republican Representative Elihu Washburne of Illinois (Cadwallader’s brother) about sensational evidence regarding Credit Mobilier and members of Congress that had emerged in a New York courtroom. John R. Young advised Washburne that the allegations would “astonish,” but added he would sit on the story because it threatened to hurt Republican prospects in the upcoming election.

Others were less hesitant to speak out. Writing in the North American Review about railroad finance in 1869, Charles Francis Adams called Credit Mobilier a threat to democracy itself, “a source of corruption in the politics of the land, and a resistless power in its legislature.”4

The Sun disclosed to the public what had been, in essence, an open secret on Capitol Hill and in some newsrooms. Once it did so, the story caught fire as newspapers reprinted versions of the Sun story and followed up with editorial commentary and stories of their own.

Before the dust settled, three congressional committees investigated Credit Mobilier’s influence on Capitol Hill. The House censured Ames and Brooks, the New York Democrat. A Senate committee recommended the expulsion of Sen. James Patterson of New Hampshire. The scandal permanently tarnished the reputation of Colfax, whose denials of involvement became increasingly improbable as the congressional investigation continued. The scandal shadowed others who were implicated – particularly Garfield – for the remainder of their careers.

Few newspaper exposes have been as consequential.

Advances in printing technology, transportation and communication – most notably the telegraph – allowed newspapers to sell more copies across wider areas and gather news from around the world. News became a commodity demanded by the public that could attract advertisers. The changing business fundamentals of the industry permitted editors and publishers to act independently of parties, although they continued to engage vigorously in the political contests of the day.

Rep. James Brooks, D-N.Y. Library of Congress.

Rep. James Brooks, D-N.Y. Library of Congress.By the 1870s, according to historian Mark Wahlgren Summers, approximately 500 newspapers from Portland, Maine, to San Francisco, published daily editions. By the end of the decade, that number almost doubled.5 As newspapers evolved into publications that provided information rather than just partisan opinion, they retained the services of men – and a few women – who could report on the events of the day.

This evolution would have significant consequences for the way in which Washington was covered. Between 1860 and 1880, the size of the congressional press gallery tripled.6 Correspondents filed daily stories, weekly “letters from Washington” that mixed news and commentary, and prowled the backrooms of Capitol Hill and government departments looking for inside information on legislation and government policy.

When they witnessed important news or uncovered something interesting, however, the correspondents were as likely to exploit that knowledge for personal gain as share it with the public.

Uriah Hunt Painter dabbled in real estate and lobbied for railroads in addition to writing for the Sun and the Philadelphia Inquirer. As a young reporter, he scooped the nation with the first report of the Union defeat at Bull Run in 1861. Before filing his story, however, he tipped off financier Jay Cooke to the Union defeat, allowing Cooke to sell off stock before share prices plummeted on the news. In the years that followed, according to Donald R. Ritchie, Cooke paid Painter to keep him apprised of legislative developments.7

Painter, rather than Gibson, could have been the reporter who broke the Credit Mobilier story after learning about the share sales in the winter of 1867-1868. Rather than expose them to the public, however, he demanded that Ames let him in on the sales. He ended up buying 30 shares, according to Ames, and was “very indignant that he did not get 50 shares.”8

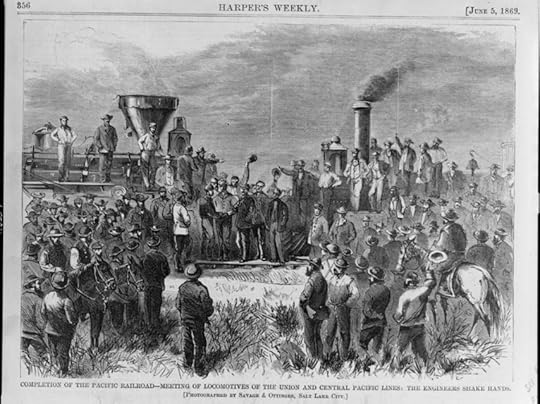

An illustration from Harper’s Weekly shows the joining of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific in Utah that completed the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Library of Congress.

An illustration from Harper’s Weekly shows the joining of the Union Pacific and Central Pacific in Utah that completed the transcontinental railroad in 1869. Library of Congress.When William B. Shaw, a correspondent for the Boston Transcript, found out that the Treasury Secretary planned to hold back payments on Union Pacific bonds, he kept that information from his paper and its readers until he could sell off his bonds. He later bragged to a congressional committee that he routinely put his private interests ahead of the public interest. “I always do these things,” he told lawmakers, “before I let anyone else know.”9

The ethical pillars that guide modern news organizations and their reporters had yet to rise. During this era, newspapers printed sensational “hoaxes” designed to boost circulation or drum up support for an editorial position. They increasingly operated independently of political parties, but their news columns routinely cheered candidates they supported and excoriated their opponents.

How did Gibson get his exclusive? That’s almost as interesting as the scoop itself. An intriguing clue appeared amid the grey front-page columns of the Sun in 1873. The newspaper attributed its scoop to “one of General Garfield’s stories, which he told three and a half years ago, concerning his transactions and the Credit Mobilier.”10

Perhaps it was the memory of this conversation that alerted Gibson to the significance of something he saw during the summer of 1872. Gibson was visiting his friend Chauncey Black at the southern Pennsylvania home of Black’s father, attorney, Democratic elder statesman and wirepuller Jeremiah Black.

While he was there, Gibson noticed that McComb arrived to consult with the elder Black. An unbylined story that appeared in the New York Times in 1885 that was clearly written by Gibson recounts how the correspondent immediately grasped that the visit had something to do with McComb’s lawsuit against Credit Mobilier. To his friend, Gibson “incidentally remarked that the case involved an ugly scandal, and that a number of distinguished public men were compromised by it.”

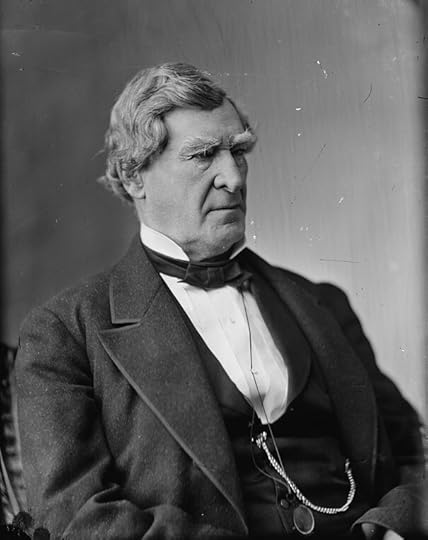

Jeremiah Black. Library of Congress.

Jeremiah Black. Library of Congress.Gibson’s unbylined account says he knew court documents were public records and that he simply needed to go to Philadelphia to get the story. His memoir also includes a fulsome denial that Jeremiah Black would do anything so despicable as leak a story to a reporter. “He was the most punctilious of men when his professional honor was involved,” Gibson asserted. “He would have suffered his right arm to be cut off before he would even indirectly have been a party to the betrayal of the most unimportant secret of one of his clients.”11

In fact, considerable evidence points to Black as Gibson’s source and enabler. After the Sun published, the Chicago Tribune sent renowned correspondent George Alfred Townsend to Philadelphia to discover how the story found its way into print. Townsend tracked down an attorney who worked for Black who possessed the deposition transcript and admitted that “a man came to see me with a letter from Judge Black” that permitted a review of the relevant documents.12

Despite its flaws, in many ways Gibson’s exclusive foreshadows the practices of modern investigative journalism. It relied not on speeches or quotes from sources but on hard documentary evidence. It needed a reporter who put two-and-two together to chase it down. It required digging (and some help from an interested party) to get the needed information.

If the challenges are similar, so are the satisfactions. Gibson put it best as he recalled the moment he discovered pay dirt as he dug through the Credit Mobilier deposition. “To say that I was startled at my find,” Gibson wrote, “would inadequately express my mental state.”13

More than 150 years later, reporters know that feeling well. The hunt for information and the thrill of discovery are timeless characteristics of investigative reporting.

___

I am the author of the forthcoming The Partisans: James G. Blaine, Roscoe Conkling, and the Politics of Rivalry and Revenge in the Gilded Age (Edinborough Press).

Congress and the King of Frauds, my account of the Credit Mobilier scandal, is available at amazon.com.

New York Sun, Sept. 4, 1872, p. 1. ︎Report of the Select Committee to investigate the Alleged Credit Mobilier Bribery, Made to the House of Representatives, February 18, 1873 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1873), p. 7. Hereafter referred to as Report.

︎Report of the Select Committee to investigate the Alleged Credit Mobilier Bribery, Made to the House of Representatives, February 18, 1873 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1873), p. 7. Hereafter referred to as Report.  ︎New York Times, Sept. 7, 1872, p. 6; New York Times, Sept. 14, 1872, p. 4.

︎New York Times, Sept. 7, 1872, p. 6; New York Times, Sept. 14, 1872, p. 4.  ︎Robert B. Mitchell, Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age (Roseville, Minn., Edinborough Press, 2018), pp. 31, 33, 44. Hereafter referred to as King of Frauds.

︎Robert B. Mitchell, Congress and the King of Frauds: Corruption and the Credit Mobilier Scandal at the Dawn of the Gilded Age (Roseville, Minn., Edinborough Press, 2018), pp. 31, 33, 44. Hereafter referred to as King of Frauds.  ︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Press Gang: Newspapers & Politics 1865-1878 (Chapel Hill and London, University of North Carolina Press, p. 10.

︎Mark Wahlgren Summers, The Press Gang: Newspapers & Politics 1865-1878 (Chapel Hill and London, University of North Carolina Press, p. 10.  ︎Ibid., pp. 81-82.

︎Ibid., pp. 81-82.  ︎Donald R. Ritchie, Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents (Cambridge, Mass., and London, Harvard University Press, 1991) p. 98.

︎Donald R. Ritchie, Press Gallery: Congress and the Washington Correspondents (Cambridge, Mass., and London, Harvard University Press, 1991) p. 98.  ︎Report, p. 31.

︎Report, p. 31.  ︎King of Frauds, p. 46-47.

︎King of Frauds, p. 46-47.  ︎New York Sun, Jan. 24, 1873, p. 1.

︎New York Sun, Jan. 24, 1873, p. 1.  ︎New York Times, Feb. 2, 1885, p. 2. Hereafter referred to as Gibson.

︎New York Times, Feb. 2, 1885, p. 2. Hereafter referred to as Gibson.  ︎George Alfred Townsend, Washington Outside and Inside (Hartford, Conn., and Chicago, James Betts & Co., 1874, p. 410).

︎George Alfred Townsend, Washington Outside and Inside (Hartford, Conn., and Chicago, James Betts & Co., 1874, p. 410).  ︎Gibson.

︎Gibson.  ︎

︎