Paul Weatherhead's Blog

November 24, 2025

A Titanic Christmas Coincidence?

It’s Christmas 1892, and controversial newspaper editor W.T. Stead has just published a short story titled ‘From the Old World to the New’. The story involves a massive ocean-going liner called the Majestic and a tragedy at sea. As the Majestic sails through dense fog crossing the Atlantic, a psychic passenger has a dream about a ship hitting an iceberg and sinking:

“…last night, as I was lying asleep in my berth, I was awakened by a sudden cry, as of men in mortal peril, and I roused myself to listen, and there before my eyes… I saw a sailing ship among the icebergs. She had been stoved in by the ice, and was fast sinking. The crew were crying piteously for help: it was their voices that roused me. Some of them had climbed upon the ice; others were on the sinking ship, which was drifting away as she sank. Even as I looked she settled rapidly by the bow, and went down with a plunge. The waters bubbled and foamed. I could see the heads of a few swimmers in the eddy. One after another they sank, and I saw them no more… Then, in a moment, the whole scene vanished, and I was alone in my berth, with the wailing cry of the drowning sailors still ringing in my ears…” [i]

Another psychic passenger has the gift of automatic writing and is in telepathic contact with a friend who was stranded on an iceberg after his ship has gone down. These two psychics then have to convince the captain to rescue the survivors of the accident.

A giant ocean-going liner crossing the Atlantic. Fog. An iceberg. A disaster at sea… All this is an eerie foreshadowing of the Titanic’s fate twenty years later. Stead set his story aboard the real White Star liner Majestic. At the time Stead wrote the story, the Majestic’s actual captain was Edward J. Smith — the same man who would later command, and die aboard, the Titanic on 15 April 1912.

Captain Edward Smith aboard the Titanic 10 April 1912

Captain Edward Smith aboard the Titanic 10 April 1912

The man who wrote this eerily prescient story, W.T. Stead, was a pioneer of tabloid style journalism, even having spent time in prison for purchasing a child in order to demonstrate that this practice was common in London in his famous ‘Maiden Tribute of Modern Babylon’ campaign against child prostitution. His sensational articles resulted in the age of consent for girls being raised from 13 to 16, the law coming to be known as the Stead Act. In the 1880s, along with many scientists and intellectuals of the time, he became fascinated by Spiritualism and mediums, a fascination seen in his story about the psychics at sea.

Like Arthur Conan Doyle, Stead’s attraction to Spiritualism and its colourful rogues gallery of charismatic mediums was understandable. Both men had lost sons in the Great War.[ii]

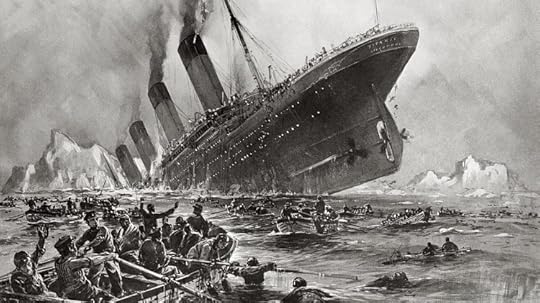

However, Stead’s story about the maritime disaster has a macabre twist. W.T. Stead was one of the 1,500 or so souls who perished when the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank below the Atlantic in 1912. He was last seen heroically giving his lifebelt to another passenger.

The Blue Island

Of course, given Stead’s interest in Spiritualism, the ghost-botherers just wouldn’t let him rest in peace. Stead supposedly wrote a book from beyond the grave called The Blue Island: Experiences of a New Arrival Beyond the Veil, in which he detailed his adventures in the afterlife to Spiritualist medium Woodman Pardoe. Pardoe supposedly channelled Stead’s account of the afterlife using the technique of automatic writing, and the book was coauthored by Stead’s daughter Estelle who was a keen Spiritualist.[iii]

The Blue Island – supposedly written by W.T. Stead after his death on the Titanic

The Blue Island – supposedly written by W.T. Stead after his death on the Titanic

So what happened to Stead after he died on the Titanic?

On realising he’s dead and that everything he’d read about the afterlife was correct, being a true journalist, he longs for access to a telephone so he can phone in the news headlines. He describes the scene from his vantage point above the Atlantic:

“A matter of a few minutes in time only, and here were hundreds of bodies floating in the water – dead – hundreds of souls carried through the air, alive… Many, realising their death had come, were enraged at their own powerlessness to save their valuables. They fought to save what they had on earth prized so much…”

Titanic Sinking by Willy Stower

Titanic Sinking by Willy Stower

When all who had perished are present and correct, some kind of astral mass transit system shoots them up into the air at terrific speed as if they’re standing on some kind of platform. Minutes later, they find themselves in a place of light and beauty where they are greeted by the souls of dead friends and relatives. This is the Blue Island, a kind of holiday camp for spirits of people who had died suddenly to help them relax after their traumatic passing.

Stead was greeted by his dead father and an old friend and shown around the Blue Island, populated by souls of people of all races. ‘Life’ there goes on as normal. People eat, sleep and smoke out of habit until they gradually begin to lose the desire to do so. They engage in their hobbies and pastimes, though soon feel pulled towards studying esoteric and spiritual matters.

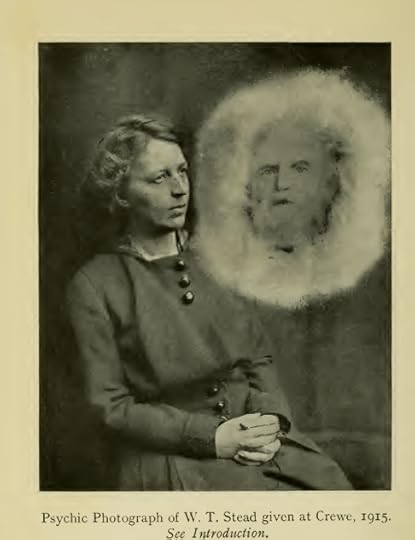

Stead spent much of his time in a building that was like a spiritual telecommunications hub where souls could contact mediums on the earthly plane and either appear before them as ghosts or send them messages. There he managed to telepath his face on to spirit photo, which I think is probably referring to the one below, taken in Crewe in 1913 or 1914.

Proof of life after death or a crude fake? You decide!

Proof of life after death or a crude fake? You decide!

Stead visited other higher planes of existence, though only vague accounts are given in the book.

The Real World

When souls are ready, they can leave the Blue Island to what Stead calls the Real World, their permanent residence in the afterlife. The Real World is very much like Earth with the same animals and plants, and the souls there spend their time developing spiritually and discarding any remaining Earth habits while still indulging in their favourite hobbies and pastimes. Here, you can live in a palace if you want, though you must earn this through spiritual development.

Advanced Spiritual Instructors interview everyone individually and in great detail about their life on Earth and every misdeed or unworthy thought they have ever had. Penance for all this is contact with Earth until your debt is considered paid.

Next, Stead tells us, souls progress to a ‘stay or go’ sphere. Here, depending on your spiritual progress you will have the option (or be obliged) to be reincarnated on Earth to learn the lessons you have yet to learn. Judging by the contents of the Blue Island, these lessons consist mostly of rambling spiritualist gobbledygook. The book was marketed as a Christmas gift, and everyone loves a festive ghost story. Speaking of which…

Epilogue

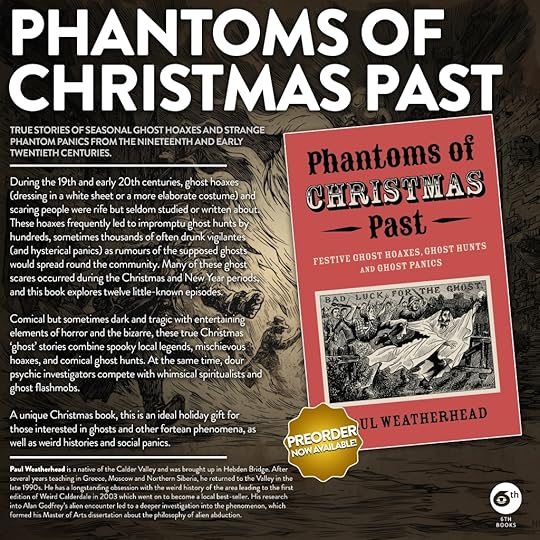

The same year that Stead wrote his prescient short story, he became interested in a notorious Christmas poltergeist episode in Peterborough involving mysterious lights, terrifying noises, spirit messages, witchcraft and a fiery hound from hell… You can read all about it in my latest book Phantoms of Christmas Past: Festive Ghost Hoaxes, Ghost Hunts and Ghost Panics.

[i] W. T. Stead “From the Old World to the New” The Review of Reviews December 1892

[ii] W. Sydney Robinson, Muckraker: The Scandalous Life and Times of W.T. Stead (London: The Rodson Press, 2013)

[iii] Pardoe Woodman and Estelle Stead, The Blue Island (London: Hutchinson and Co, 1922)

For more resources on Stead see https://attackingthedevil.co.uk

October 27, 2025

Stoned Spooks and Other Ghosts That Time Forgot…

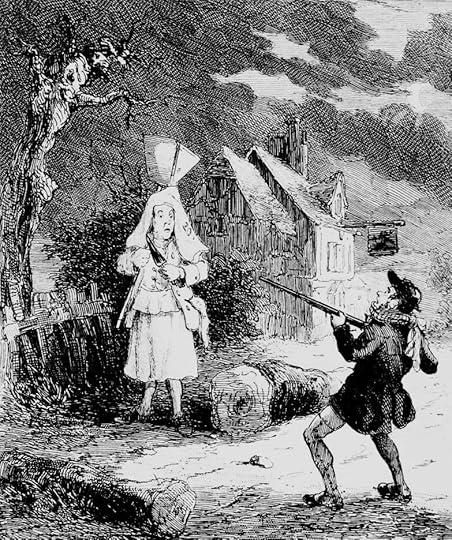

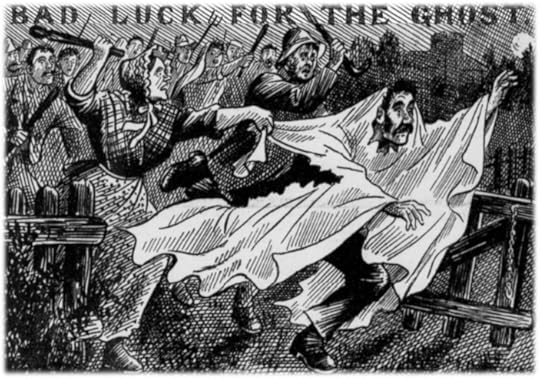

As Halloween approaches, our thoughts often turn to ghostly matters. I’ve long been fascinated by the forgotten phenomenon of ‘playing the ghost’ – dressing as a ghost and hanging out in spooky locations to scare the wits out of passersby. Sometimes the pranksters wore just a white sheet over their heads, though some would use devil masks, animal skins, outlandish clothes and luminous paint to create more imaginative spooks.

Often gangs of young men would patrol the streets hoping to catch the ghost and give him a well-deserved drubbing. These ghost hunts would frequently degenerate into a drunken riot with the ghost hunters dressed as women hoping to honey trap the ghost into attacking them.

This strange hobby of playing the ghost was rife throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, and some of the episodes were immortalised by images from the tabloid known as Britain’s worst newspaper, The Illustrated Police News.

Giant Ghosty Scares the Postie: The Garstang Ghost (1881)

In September 1881, an unnamed postman was on his way to pick up the mail that was arriving on the night train to Garstang, near Preston in Lancashire. As he walked down the dark country lane, a white ghostly figure appeared before him. It was, according to press reports, of ‘abnormal stature’ and a ‘horrid pallor of hue’. The figure seemed to be giving mysterious and portentous signs in a ‘variety of terror-striking gestures….’

The moment is captured in a drawing from the Illustrated Police News depicting the poor ‘palpitating postman’ dropping his letters as the giant spectre looms over him.

The Garstang Ghost in the Illustrated Police News 10 September 1881

The Garstang Ghost in the Illustrated Police News 10 September 1881The postman took the ghost’s gestures as a warning not to proceed and he turned and fled. So terrified was he that he gave up his job rather than risk encountering this fearsome vision again.

The ghost was also encountered by a young servant girl. She described its fearsome height, its white robes and ominous gestures. She threw her apron over her head and ran home. We are told that she has not spoken since and retired to bed in shock.

Each night gangs of young men armed themselves with stout cudgels and patrolled the streets of the town, though it seems it was never caught. Lucky for him. When ghost hoaxers like this were caught, they were often badly beaten and dumped in the nearest canal, river… or sewer.

The press reported a few days later that the ghost had disappeared, and that the suspect was a resident of nearby Barnacre.[i]

Ghost Gets Stoned: The Woolwich Ghost (1897)

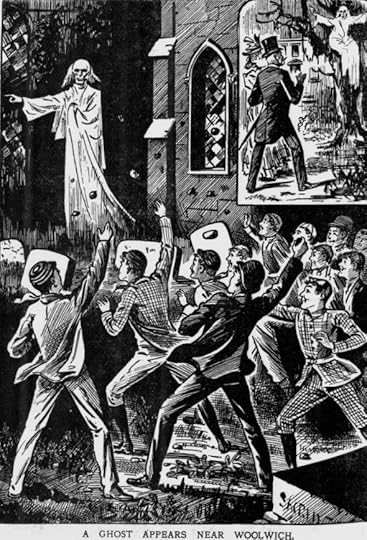

As Halloween approached in 1897, the children attending the schools in the grounds of Saint James’ Church, Plumstead in London got the fright of their lives. A ghostly figure in white was seen by several pupils who were so scared they had taken to their beds.

As news spread, a gaggle of around 100 young lads turned up on subsequent nights waiting for the ghost to reappear. When it did, the boys employed ‘the usual tactics of Plumstead lads’, in other words, ‘throwing stones and bad language’. The stone throwing broke several windows in the grounds.

Schoolboys pelt the Woolwich Ghost in the Illustrated Police News 6 November 1897

Schoolboys pelt the Woolwich Ghost in the Illustrated Police News 6 November 1897Three constables soon arrived and arrested the ringleaders of the boys who were later charged with disorderly conduct, and the ghost fled the scene.

Later, the ghost was seen in similar white attire up a tree in the garden of Mr Jolly a Justice of the Peace. The culprit turned out to be a cycle maker who was committed to an asylum by his friends for his own safety before he could be arrested. The man was described as being of Herculean strength and it took several police officers to get him out of his house.[ii]

Impromptu ghost hunts like this were often carnivalesque and transgressive. It would have been very tempting for many of the boys to deliberately miss the ghost and put a rock through the school window as an act of rebellion.

Naked Lady Ghost Gets Stoned (1887)

Exactly 10 years earlier, there was another ghost stoning in the Woolwich area. Rumours spread that a naked lady ghost was appearing in the upstairs window of a shop on the corner of Ogleby Street.

Hundreds gathered around the shop, including gangs of young lads. When someone shouted ‘there she is!’, the boys unleashed a volley of stones at the window. Hundreds more gathered and blocked the whole street the following night and the police found it difficult to keep order, especially when the cry of ‘there she is’ rang out and the gangs of youths began hurling stones.

These episodes continued for a week, with the region said to be in a ‘perpetual ferment’ over the naked lady ghost and the rock-throwing youths. Eventually, two teenage boys who were taken to be the ringleaders were arrested and charged with disorderly behaviour. They were given seven days in prison.

Mrs Marsh, the landlady of the shop, said that if anyone was seen in the windows it was probably one of her lodgers, though they denied any trickery. Mrs Marsh also told the press that someone had come into her house and walked along the corridor moaning in a ghostly fashion.

There’s some indication that Mrs Marsh and her lodgers didn’t get on, so it’s quite possible the episode was caused by one of them pretending to be a ghost in front of the upstairs window. More plausibly, based on the press accounts, the rumours may have been maliciously started by the gangs of stone throwing teenagers.[iii]

Epilogue

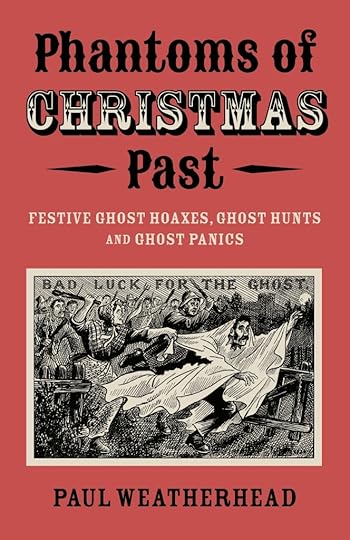

Did I mention I’ve got a new book out? It’s called Phantoms of Christmas Past: Festive Ghost Hunts, Ghost Hoaxes and Ghost Panics. It features forgotten true stories of Christmas ghost hoaxes that are dark, comic, tragic and bizarre.

And it’s never too early to start your Christmas shopping!

Available wherever you get your books from, or online here.

[i] ‘A Troublesome Ghost’, Staffordshire Sentinel, 5 September 1881, p.4: ‘The Ghost at Garstang’, Preston Chronicle, 10 September 1881, p.6; ‘A Ghost at Large’, Illustrated Police News, 10 September 1881, p.4: ‘Disappearance of the Garstang Ghost’, Lancaster Gazette, 21 September 1881, p.2;

[ii] ‘A Ghost at Plumstead’, Brockley News, 29 October 1897, p.4; ‘A Ghost Appears Near Woolwich’, Illustrated Police News, 6 November 1897, p.6

[iii] ‘Woolwich Ghost’, Greenwich and Deptford Observer, 12 August 1887, p.5; ‘A Ghost Story at Woolwich’, Kentish Mercury, 12 August 1887, p.5; ‘Stoning the Woolwich Ghost’, Greenwich and Deptford Observer, 19 August 1887, p.2

October 1, 2025

The Pudsey Bitch Daughter

The West Yorkshire town of Pudsey, about halfway between Leeds and Bradford, famously gave its name to Pudsey the Bear in the BBC Children in Need charity campaigns. But it also gave its name to a far more sinister figure that haunted the nightmares of many: the Pudsey Bitch Daughter…

You find yourself suddenly awake in the middle of the night unable to breathe. Panic turns to terror as a sinister figure approaches your bed and climbs on top of you as you lie utterly paralysed and unable to cry out. As the figure kneels on your chest crushing the life out of you, you see the horrible leering face of a witch and clutched in her hand is a carving knife which she raises above her head, and as you watch on spellbound in immobile horror, she plunges it into your thudding heart. You have just encountered the Pudsey Bitch Daughter.

The only historical reference I can find to the Pudsey Bitch Daughter (or ‘Dowter’ in local dialect) is in Joseph Lawson’s 1887 book Letters to the Young on Progress in Pudsey During the Last Sixty Years.[i]This suggests belief in – or at least an awareness of – the Pudsey Bitch Daughter lasted well into the early to middle nineteenth century.

But who or what was the Pudsey Bitch Daughter?

Bitch Daughters

The Bitch Daughter was a common name for a demonic witch-like figure that was said to sit upon her victim’s chest and suffocate them. A common expression was to be ‘ridden by the bitch daughter’ – in other words, to have suffered an attack from this nocturnal entity.[ii]

These attacks are what we call today sleep paralysis: your body in immobilised as it would be when you’re dreaming, but you feel fully conscious. Being paralysed increases the feeling of panic, and the sleep disorder is often accompanied by frighteningly real hallucinations or a sense of a malignant presence in your bedroom.

Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare

Henry Fuseli’s The NightmareThe experience is fairly common. One study found that around a third of college students had experienced a bout of sleep paralysis.[iii] However, other studies get very different results, and this may be down to how questions in surveys are phrased, how such experiences are viewed in the local culture or innate or cultural differences in prevalence in populations.

The experience of sleep paralysis has a common core of characteristics: feeling unable to move, negative emotions, a sense of a sinister presence and a tightness in the chest. However, the entities involved differ across cultures. In Newfoundland, it would be a hideous hag, in China it might be a ghost, in Egypt it could be a jinn and in Japan a demon.

In Europe a few centuries ago, experience of sleep paralysis would be explained as a visit from an incubus or succubus – horny demons that would have sex with their sleeping victim.

The Bitch Daughter is another way of describing these experiences, with the Pudsey Bitch Daughter being a local variant on this.

Is it the case that the experiences of sleep paralysis create the folklore around these entities, or does the retelling of these stories of nocturnal attacks make a population more likely to interpret sleep paralysis with reference to the folklore?

It’s hard to tell, and the influence may run both ways. In my own experiences of sleep paralysis (see link below), I saw a monkey faced demon sitting on my chest and crushing the life out of me. But I can’t help but wonder if this was influenced by a painting known as The Nightmare by Henry Fuseli from 178I which I was familiar with from the cover of the Penguin Classics edition of Frankenstein.

Hag Stones

So how would the good people of Pudsey go about protecting themselves from the Bitch Daughter?

It’s likely that they used hag stones – pebbles, slates, flints or other stones with a natural hole in them. These would be tied to the bed with some string through the hole in the stone to ward off evil hags like the Pudsey Bitch Daughter who were wont to attack helpless victims in their sleep. Some folklore says the stones must be stolen or given to be effective, rather than found oneself, though in the available accounts it seems clear that they were passed down in families and this was thought to increase their potency.

A hag stone… don’t know where, don’t know when

A hag stone… don’t know where, don’t know when

In Yorkshire, the magic was said to be inactive until or unless the string or cord was looped through the hole and a knot tied. Furthermore, a new string had to be tied in place before cutting an old worn out one, or the magic would dissipate.

Troublesome demonic witches like the Pudsey Bitch Daughter not only haunted people in their beds. When horses were found in their stable sweating and mysteriously exhausted in the morning, it might be assumed that the animal had been ridden by witches throughout the night. A hag stone hung in the stable was thought to offer protection.[iv]

Hag stones were convenient folk magic. No rituals, blessings or magic words required. No priest, cunning man or wise woman need be employed. You didn’t even have to look for one – they were said to only work if you hadn’t been purposefully searching for one. All you did was tie a piece of string through the hole and hang it in the desired place.

Although the Pudsey Bitch Daughter has vanished into history, hag stones have not. They were still in use in parts of rural Yorkshire in the early twentieth century to guard against witchcraft.[v]

Occultist Aleister Crowley was rumoured to have cursed the town of Hastings so that whoever tried to leave would be condemned to eventually return there. The only way to escape was to take a stone with a hole in it – a hag stone – from the beach, according to local legend.[vi]

Epilogue: The Hat Man

Although the Pudsey Bitch Daughter remains elusive, she is part of a tradition of shadowy entities inhabiting the edges of our consciousness. In recent years, the Hat Man has emerged as a sinister figure haunting people’s nightmares. Victims have described this mysterious humanoid figure with his trademark Freddie Krueger fedora appearing before them when they suffered from attacks of sleep paralysis or when they had taken too much Benadryl, an over-the-counter anti-allergy medication.

Artist’s impression of the sinister sleep paralysis demon the Hat Man (Amanda Aquino 2001)

Artist’s impression of the sinister sleep paralysis demon the Hat Man (Amanda Aquino 2001)

Personal accounts with the Hat Man have spread since the early 2000s and become a popular internet meme.[vii] This has allowed it to spread far and wide across cultures far more effectively the Pudsey Bitch Daughter could ever dream of.

So if you happen across a stone with a hole in it, pick it up and take it home. It might get you a better night’s sleep…

The author with a double hag stone found on the Yorkshire coast

The author with a double hag stone found on the Yorkshire coast

For my adventures with sleep paralysis and a demon haunted light switch, see here

For more horny demons, see here

[i] Joseph Lawson (1887). Letters to the Young on Progress in Pudsey During the Last Sixty Years, p.49

[ii] Karen Stollznow (2024). Bitch: The Journey of a Word (Cambridge University Press), p.26

[iii] G. Benham, (2020). ‘Sleep paralysis in college students’, Journal of American College Health, 70(5), 1286–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2020.1799807

[iv] J. Geoffrey Dent (1965). ‘The holed stone amulet and its uses’, Folk Life, 3(1), pp.68-78, doi:10.1179/flk.1965.3.1.68

[v] ‘Guard against witches’, Yorkshire Evening Post 12 April 1927, p.7

[vi] https://www.hastingsinfocus.co.uk/2021/10/26/crowleys-curse-you-can-check-out-any-time-you-like-but-you-can-never-leave/

September 2, 2025

Croydon Cat Killer: Mystery Solved!

A maniac is stalking the streets of Croydon, killing and dismembering cats and leaving the remains in a gruesome display to maximise the shock and horror when the corpse is discovered by owners.[i] Over 500 cats have so far fallen victim to the maniac, and the killer is likely a psychopath who will sooner or later start taking human life.

Newspapers and local TV stations interviewed distraught owners and showed photos of the unfortunate pets. At the same time, tabloids found puns impossible to resist. The Sun referred to the Croydon Cat Killer as ‘Jack the Ri-purr’ and the Purrminator’.

The Sun 11 December 2015

The Sun 11 December 2015I researched and wrote about the history of pet killing panics, including the one in Croydon in the book I co-wrote with Robert Bartholomew, Social Panics and Phantom Attackers, so I’ve spent a lot of time examining this and similar episodes.

So, let’s solve the mystery of the Croydon Cat Killer…

The Croydon Cat Killer

First, the good news. There is no Croydon cat killer, despite the unquestioning media reports, social media posts, podcasts and animal charity campaigns. The Croydon Cat Killer doesn’t exist.

A 2022 study published in the journal Veterinary Pathology examined the corpses of 32 ‘victims’ of the Croydon Cat Killer. The postmortems revealed that fox DNA was present in all cases, though only ten kittens had actually been killed by foxes. Eight of the cats had died of heart failure, six had been hit by traffic and the others had died from liver failure or from ingesting poison. Foxes had mangled all of the corpses. There was no human involvement.

Expert in fox behaviour Stephen Harris came to similar conclusions. Foxes will often chew off heads and limbs from roadkill, leaving the carcass looking as if it had been deliberately displayed.

The Sun 28 September 2018

The Sun 28 September 2018Pet killer panics have been happening for over a century and tend to follow a pattern. First there is a cluster of mysterious pet deaths. These are reported in the media (or social media). A figure of authority – usually a vet or someone from an animal charity – states that the deaths were deliberately caused by humans. More and more cases are reported, police investigate but find nothing. An individual or small group (what sociologists might call ‘moral entrepreneurs’) then task themselves with catching the killer, seeing themselves as intrepid detectives on the hunt for an evil pet killing maniac. They spread the word through media campaigns and the fear of the mythical pet killer spreads. Finally, it all blows over, only to reappear some time later in another town.

The Croydon panic began in 2014 when a number of mutilated cats were reported. Many concluded that there must be a cat-hating serial killer on the loose – why else would the cats be mutilated and left for the devastated owners to find? The catalysts in the Croydon panic were founder members of animal charity SNARL, Boudicca Rising and Tony Jenkins, and they made it their mission to put a stop to the killings. After a cat was found mutilated, Boudicca and Tony would arrive at the grisly scene like Moulder and Scully from the X-Files investigating a mystery.

Tony Jenkins and Boudicca Rising (Metro 28 August 2025)

Tony Jenkins and Boudicca Rising (Metro 28 August 2025)They’d interview distraught owners, take photos of the remains and search for clues. Tony’s freezer was stuffed with the dismembered corpses of cats so they could get postmortems done. When the postmortems showed no human DNA on the cats, Boudicca and Tony concluded that the killer must be forensically aware.

When you’re in the grip of a phantom attacker panic, you don’t believe what you see, you see what you believe, and that was what was happening to Boudicca and Tony. Tony would claim that the cuts made in the cat carcasses examined were ‘too clean’ to have possibly been caused by foxes scavenging, echoing the claims made by UFO believers that cattle mutilations were too clean to have been done by scavengers so must have been done with an alien laser. However, corpses bloat and burst, giving the impression of a surgical incision, and this likely explains the apparently clean cuts found in some of the cats.

Nevertheless, and despite regular debunking of the Croydon Cat Killer myth, Boudicca Rising and Tony Jenkins continue their campaign to catch a non-existent maniac. Newspapers, podcasts and radio and TV documentaries continue to follow them and give their campaigns publicity. Their new charity, SLAIN (South London Animal Investigation Network), is again popping up in news reports with eager journalists lining up to go out with them on night patrol hunting for the killer.

Satanic Cat Killers

Strangely, a very similar cat killing panic occurred in the Croydon area in the 1990s. This time, when mutilated cats were found, rumours spread that Satanists were using the pets in depraved rituals. Stephen Harris, the fox expert referred to above, described how police delivered a sack of headless cats to him and asked him to investigate. He concluded that most of the cats had been run over and then scavenged by foxes, whose weak jaws mean they often gnaw heads, tails or limbs off roadkill they find. The police had spent 13 months hunting for a coven of cat killing Satanists that didn’t exist.

Epilogue: The Dog Question and the Cat Question

Pet killing panics tend to reflect the concerns and anxieties of the time. In Weird Calderdale, I wrote about the Halifax Dog Poisoner episode of 1899 when a number of prize hounds were found apparently poisoned. A vet, the appropriately named Mr Walker, told the press that he was sure that there must be a maniac with a hatred of dogs at large in Halifax, though in the end the poisonings seemed to stop. It was more likely that dogs were dying of natural causes or had ingested some arsenic probably intended for rats. In any case, just like Boudicca Rising and Tony Jenkins in the Croydon episode, Mr Walker is the expert who really gets the panic going.

The Halifax Dog Poisoning panic spread in the context of what was called ‘the Dog Question’ – should dogs be allowed to roam free in the streets? Should they be muzzled in case they attack a child? What about the dangers of rabies? There was intense public debate and concern about dog ownership at the time, especially as raising prize-winning animals and entering them into competitions (‘dog-fancying’ or ‘the Fancy’ as it was called) was particularly popular in Halifax and other northern industrial towns at the time.

In recent years, though, the Cat Question has emerged. Should cats be kept as house pets, or should they be allowed to freely roam, knowing that they will likely hunt and kill birds and other wildlife? Outdoor cats are also more likely to become ill, be run over, get lost or decide to adopt another owner in another house. The average lifespan of an indoor cat is 12-15 years. The average lifespan for a cat allowed to go outside is 2-5 years.[ii]

And it’s not psychopathic kitty killers that are responsible for this. As we argued in Social Panics and Phantom Attackers: ‘Allowing the death of one’s cat to be projected onto a depraved cat slayer may reflect anxiety and guilt about the cat’s role as predator and the pet owner’s responsibility for their own cat.’[iii]

Of course, people are capable of great cruelty to animals and it’s well-known that some psychopathic serial killers started on animals before moving on to humans. There are some real cases of sadistic cat killers. But the Croydon Cat Killer has all the signs of being a phantom attacker panic, a kind of hysteria where the community fears an imaginary monster lurking in the shadows – a bogeyman that reflects their own fears and anxieties.

Two things are clear from my research on pet killing panics. The first is that charismatic, well-meaning and dedicated animal charity volunteers are very often central to the spread. They collect ‘evidence’, organise online campaigns and get media coverage, but one can doubt their expertise in forensics. As I said, during phantom attacker panics, people see what they believe rather than believe what they see.

The second is that panics like these come and go and lessons are never learned. The Croydon Cat Killer will have another day in the sun as a number of podcasts and a BBC radio documentary come out. But the bubble will burst and it will all blow over – until the next time. As the Purrminator said: I’ll be back!

Ozzy my new kitten

Ozzy my new kitten[i] Brooke Davies, ‘Is the Croydon cat killer back? Gruesome incidents hint “he never went away”’, Metro, 28 August 2025. Available at: https://metro.co.uk/2025/08/28/croydon-cat-killer-back-data-shows-never-left-23914052/

[ii] https://vetexplainspets.com/indoor-vs-outdoor-cat-lifespan/

[iii] Robert Bartholomew and Paul Weatherhead, Social Panics and Phantom Attackers (Palgrave Macmillan: 2024), p.270

August 28, 2025

Playing the Ghost

Imagine walking alone late at night along a lonesome dark avenue with a church yard full of teetering gravestones on one side of you and the jagged remains of a crumbling church on the other. Ahead of you in the gloom, you see a white figure glowing eerily, cavorting and striking dramatic poses while emitting melancholy groans.

He seems to be draped in a white sheet and covered in luminous paint. He’s sporting devil horns and wearing an animal mask. Perhaps it’s someone having a drunken lark, you think. But could it be a maniac who means you harm – why else would he be lurking among the tombs in the dead of night? Or, quite possibly, the dark gloomy atmosphere and your jangling nerves convince you that it’s a spirit from beyond the grave…

What would you do? It would take courage to continue on your way, ignoring the prancing, moaning figure in white. Would you turn and run? Would you assume it’s a prankster and attempt to pull off his ghostly disguise and deliver a punch to the miscreant’s nose?

This is a dilemma faced by countless individuals throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth century when such ghost hoaxes were ubiquitous. The practice of ‘playing the ghost’ as the press called it was so common that almost every town in the country suffered from it regularly. These hoaxes are a strange but largely forgotten slice of weird history, and one that’s fascinated me for a long time.

Perhaps because of the lengthening nights, these hoaxes would often begin around Halloween, escalate over November before peaking around Christmas and New Year. We love ghost stories at Christmas, so this was the ideal time for newspapers to pick up on the ghost rumours, but also to exaggerate and sensationalise them. It’s these bizarre and darkly comic festive ghost hunts, ghost hoaxes and ghost panics that I’ve unearthed for my book Phantoms of Christmas Past.

Playing the Ghost

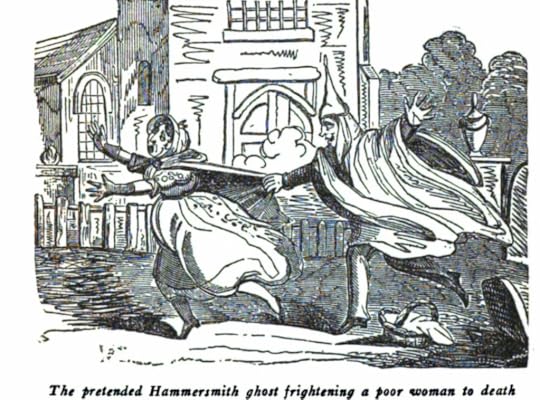

A classic example of one of these hoaxes is the story of the Hammersmith Ghost. Towards the end of 1803 a prankster had been scaring the citizens of West London by jumping out on them at night wearing a white sheet or an animal skin. Some of the ghost’s victims were so shocked that they were driven mad and never recovered, or so the press informed us.

As news of the ‘ghost’ spread, many were afraid to venture out at night and extra patrols of watchmen and vigilantes were organised. Other pranksters were inspired by what they read in the papers and carried out copycat hoaxes. On Christmas Day 1803, a coachman driving past a Hammersmith field saw a ghostly figure in white that was covered from head to foot in pigs’ bladders filled with dried peas – a common but grisly children’s toy at the time. The bladders rattled eerily as the ghost pranced and struck melodramatic poses, causing the coachman to flee in terror. Other accounts talked of the ghost breathing fire or vanishing into the ground.

As Christmas gave way to New Year, a febrile hysterical panic gripped Hammersmith, and that’s when events turned tragic.

After a night of drinking, excise man Francis Smith decided to confront the ghost on 3 January 1804. Waiting on the dark winter streets, Smith eventually came across a white clad figure and asked it to identify itself. When no reply came, Smith pulled out a fowling gun and fired. He had killed innocent bricklayer Thomas Milward, who was wearing the white clothing that was typical of his profession.

Francis Smith confronts the ‘ghost’

Francis Smith confronts the ‘ghost’Francis Smith was found guilty of murder and sentenced to death, though was soon after pardoned. The Hammersmith ghost pranks were later blamed on shoemaker John Graham who admitted to dressing in a scary white costume to exact revenge on his apprentice for terrifying his children with spooky stories. Graham was certainly not the only ghost hoaxer at work in Hammersmith, but he was a convenient scapegoat which allowed the panic to dissipate.

Ghost Panics: Playing the Ghost goes Viral

The story of the Hammersmith Ghost demonstrates how these ghost hoaxes could escalate into full-blown panics where people were afraid to walk the streets at night and well-meaning but not particularly sober vigilante groups were often formed. In some cases, such as when the Hammersmith Ghost made a comeback around Christmas 1824, burley young men walked the night streets dressed as women to try and honeytrap the ghost into attacking them. These cross-dressing ghost hunts were fairly common in the nineteenth century when ghost pranksters were at work, and were probably more of a drunken lark than a serious attempt to catch the ghost. However, if a ghost was caught, he would likely be badly beaten and perhaps dumped in a nearby river, canal or sewer. There was a great deal of anger directed against these hoaxers and the Hammersmith Ghost panic shows how things could easily turn ugly if you were in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Ghost Busters

On many occasions, the vigilantes would be joined by hundreds of enthusiastic ghost hunters who’d heard rumours or read press reports about the ghost and wanted to be part of the fun. This sometimes created the conditions for what I’ve called the ghost hunting flashmob – spontaneous gatherings of enthusiastic, mischievous, and probably inebriated amateur psychic investigators.

This is what happened in Islington in 1899. A letter by someone calling himself James Chant was printed in the Islington Gazette and claimed that a ghost had been seen on Christmas Day haunting the graveyard of Saint Mary’s church. Soon, hundreds of people congregated in the churchyard and had a riotous time making uncanny noises, screaming, chasing one another among the tombs and pretending to be ghosts. The press called it ‘a vulgar riot’ and noted that many of the ghost hunting revellers returned home with their watch or wallet missing. The press speculated that the rumour had been started deliberately by thieves who would find it very easy to pick the pockets of the drunk and jostling crowds that would inevitably rush to the site of the supposed haunting.

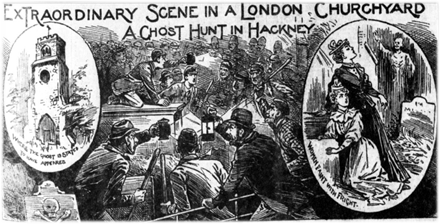

Hackney Churchyard ghost hunt 1895

Hackney Churchyard ghost hunt 1895A beautiful example of Christmas ghost flashmobs involves the splendidly monikered Clanking Ghost of East Barnet. When accounts of this skeletal figure in his long cloak appeared in the press in the Christmas of 1926, it sparked not only a discussion in the local council over whether watchmen guarding haunted locations should be paid extra, it also led to thousands of ghost hunters descending on East Barnet every Christmas well into the 1940s. The ghost was said to be that of Sir Geoffery de Mandeville, a rebel baron who died in 1144, and it was the metallic rattling of his armour that gave him his nickname of the Clanking Ghost of East Barnet.

The Clanking Ghost of East Barnet

The Clanking Ghost of East BarnetSerious psychic investigators and spiritualists descended on the town every year hoping to make contact with Sir Geoffrey, but hordes of rowdy ghost hunters full of the Christmas spirit blocked the roads and foiled their attempts.

These Christmas ghost hunts, hoaxes and panics combine local folklore, trickery, comedy and tragedy. They still have something to teach us about how the media uncritically spread gossip and rumours and how easily populations can be swept up in panics. But these little-known episodes also reflect our love for scary stories, our penchant for mischief and riotous festive merriment.

Out now!

Out now!

July 24, 2025

A Yorkshire Ghost: The Poltergeist of Storrs Hall

Christmas 1877 at Storrs Hall was not a merry one at all. The gloomy house, which stood in the hamlet of Storrs on the moors between South Yorkshire and Derbyshire, was tormented by a restless and destructive presence. The Storrs Ghost, as it was dubbed by the press, became a sensation as hundreds came to investigate this window smashing poltergeist…

Storrs Hall, as hallucinated by our AI overlords

Storrs Hall, as hallucinated by our AI overlords

The Ghost of Storrs Hall

Storrs Hall was occupied by Mr and Mrs Ibbotson and their fourteen-year-old servant girl Anne Charlesworth, though a milk maid and farm labourers were also employed to work on the farm. It was around Christmas 1877 that life at the Hall took a turn for the weird.

Inexplicable rappings were heard throughout the farm. The nervous farm hands had probably heard rumours of ghostly activity in the house. On one occasion a farm hand and a milkmaid heard banging on the farm door, but when they opened it, no body was to be seen. They fled the house in terror. Later, one of the farm labourers stood in wait behind the door so that if a human culprit was responsible, he would be sure to catch them. Still the rapping happened, though the man saw nothing.

As well as the odd noises scaring the staff, the washing line would be mysteriously cut and the clothes flung out into the road.

But it seems this ghost really loved the sound of breaking glass. Windows would smash without warning in different parts of the house. When the glazier came to repair a window, it would almost immediately be broken again. Whenever any of this this happened, farm hands would grab their hayforks and go tearing around the farm hoping to catch a prankster, but they never found a sign of any human involvement.

When news of the strange events spread round the area, many locals concluded that the house was haunted. As was common in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, crowds went to see the house they’d heard about in local gossip or read about in the press. There they might share their own spooky experiences and theorise about the supposed ghost. It’s very likely, especially at Christmas, that they were full of the spirits of the season, and these impromptu ghost hunts could sometimes become riotous, though thankfully this did not happen at Storrs. Nevertheless, a large number of men patrolled the farm grounds with stout sticks, but the destructive presence evaded their searches and carried on its mischief.

Storrs Hall was owned by Mr Thomas Wragg, an industrialist who had made his fortune in the local firebrick industry, and after witnessing the mysterious window smashing for himself, offered a ten-shilling reward for information as to who was responsible.

Within a week of the troubles starting, Mrs Ibbotson was too afraid to sleep in the house and would only enter it with a policeman present.

Poltergeist Cluedo

Seargent Hobson of Hillsborough police station was sent to Storrs Hall to investigate, so let’s join him in a game of poltergeist Cluedo. Who was responsible for the destructive spooky pranks that were terrifying the maids and farmhands of Storrs Hall? Seargent Hobson noticed that the windows appeared to have been broken from the inside, and suspicion fell on servant girl Ann Charlesworth. She denied everything.

Then she admitted that she may have broken one of the windows but was certainly not responsible for everything else.

Finally, and sobbing bitterly, Anne confessed that she was indeed the ghost. It all started when she rapped on the barn door while a servant was milking a cow and scared him silly. She was somewhat taken aback as to how successful her little prank had been. She went on to cutting the washing line, banging on doors and throwing stones through windows. The Seargeant was astonished at the girl’s cunning and ingenuity in evading capture.

Anne Charlesworth expressed remorse at her actions and promised not to do it again, though it seems likely that she would have lost her position and returned to her parents in Deepcar.[i]

Poltergeist pranks were commonly played by servant girls in the nineteenth century and beyond. I suspect they still are. Men and boys carried out ghost hoaxes too, though they had more freedom to do so outside the home, usually by donning a white sheet or scary costume and jumping out on strangers in the dark. For more on this bizarre phenomenon, see my new book, Phantoms of Christmas Past: Festive Ghost Hoaxes, Ghost Hunts and Ghost Panics.

Available for pre-order wherever you get your books from!

Available for pre-order wherever you get your books from!

Some scholars might see cases like Anne’s as an act of protest against a repressive patriarchal society, or something along those lines. And perhaps it was an act of rebellion on Anne’s part – she was clearly intelligent (or at least deceptive and cunning) and her talents may have been wasted in Storrs Hall, or so she might have felt.

Folklorists might say she was engaging in ostension, the acting out of legends in real life. Indeed, the Hall had a reputation for being haunted (according to one anonymous old man mentioned in a newspaper). But this doesn’t really address Anne’s motive.

Psychic investigators might say that young girls are more likely to exhibit telekinetic powers, and that’s why poltergeist cases frequently involve their presence. However, there are very many cases where maids, servants and young family members have confessed or been caught in the act of faking poltergeist activity. There is a longstanding belief in investigators of psychic phenomena that a silly young girl could never pull the wool over their eyes. They are wrong.

Some people are mischievous and enjoy scaring people then watching the drama unfold. Perhaps what starts as a joke suddenly takes on a life of its own and spirals out of control. Poltergeist scares often led to huge crowds of rowdy, drunk amateur ghost hunters swarming round the supposed haunted house

When Anne first terrified the hapless servant as he milked a cow, she made a shocking discovery that is important to understanding episodes like this. Fooling people is easy.

The Storrs Ghost featured in the Illustrated Police News 19 January 1838

The Storrs Ghost featured in the Illustrated Police News 19 January 1838Epilogue

An interesting little footnote to this story comes in the form of a letter from someone signing himself as J.A.G. and printed in the Sheffield Independent in early January at the height of press interest in the Storr Ghost.[ii]

His friends had for some time been complaining about the incessant ringing of their doorbell and they suspected it was a gang of young lads up to no good. Others in the household thought it was spirit activity and were greatly alarmed. Nevertheless, the author of the letter volunteered to watch outside the house, and if anyone tried to ring the doorbell, he could pounce on them.

As he waited, the bell started clanging, so he ran to the door to find nobody in sight. He searched the garden to no avail. This seemed to confirm to some of the residents that there was something supernatural afoot. The ringing continued night after night, with the young servant girl frequently having to trudge all the way from the kitchen, where the bell was, to the front door only to find no one there.

The author immediately suspected the servant girl who denied everything, and her employers scorned the accusation. However, when the intrepid author investigated the kitchen, he noticed suspicious marks on the wall near the bell. Furthermore, whitewash from the wall was on the handle of a broom standing nearby. He suspected the girl had been hitting the bell with the broom handle and confronted her with the evidence. She once more denied everything but left her employment soon after.

However, the family later discovered that the servant had indeed been the culprit but was aided by her boyfriend who sometimes rang the bell from outside before running away. This meant that the family would have heard the bell ring when the girl was in the room with them and so removed suspicion from her.

For more Poltergeist Cluedo, see below:

The Gorefield Ghost

A Lancashire Ghost Riot: The Up Holland Poltergeist

Sweary Mary ~ The Clonmel Ghost

[i] ‘A ghost at Sheffield’, North Derbyshire and North Cheshire Advertiser, 12 January 1878, p.2: ‘The latest ghost story’, Wakefield Free Press, 12 January 1878, p.5; ‘A Yorkshire Ghost’, Illustrated Police News 19 January 1878, pp.1-2

[ii] J.A.G. ‘The Ghost at Storr Hall’, Sheffield Independent, 8 January 1878, p.8

July 10, 2025

New Book Announcement! “Phantoms of Christmas Past: Festive Ghost Hoaxes, Ghost Hunts and Ghost Panics”

My new book is available for pre-order wherever you get your books from and will be out at the end of August. More details and reviews below…

Some advanced reviews:

Folklore, spooky legends, weird experiences, ghost hoaxes, and riotous drunken ghost hunts all collide in a unique darkly comic book of true Christmas ghost stories…

I’m really excited about this coming out. If you liked Weird Calderdale, then you’re sure to enjoy this. Or buy it as a Christmas present for your weirdest friend….

June 17, 2025

A Lancashire Ghost Riot: The Up Holland Poltergeist

In the summer of 1904, the village of Up Holland in Lancashire was in the grip of a ghost fever. A destructive poltergeist hurled lumps of mortar, stones and weighty tomes around a haunted bed chamber, and adventurous local councillors, police and spiritualists tried to solve the mystery, as did thousands of drunken ghost hunters in the graveyard outside the house.

Mysterious flying masonry, ghost busting councillors, lascivious highwaymen, riotous revellers and Lancashire’s terrifying hell hound, the skriker… this is the story of the Unseen Agency in the haunted chamber: the Up Holland Ghost.

The House by the Cemetery

The haunted chamber in the haunted house overlooked the cemetery, which you might think rather gloomy. Beneath its window was the grave of highwayman George Lyon, executed in 1804. Just beyond the church yard can be seen the ruins of an ancient abbey.

On the other hand, the house had a pub on either side of it. The house by the cemetery was a place where spirits of the present world and spirits of the next were in close proximity. It was one of the oldest houses in the village of Up Holland, about 4 miles from Wigan in Lancashire.

Sometime in July 1904 the occupants of the house, widow Mrs Winstanley and her three sons and two daughters, began to be troubled by strange and violent phenomena. In the room overlooking the graveyard, stones and chunks of mortar from the wall would fly across the room. Sometimes strips of wallpaper would be torn from walls for no reason. A hatbox and a weighty volume on the history of England were all hurled around the room in the hours of darkness by what the newspapers enigmatically called the ‘unseen agency’.

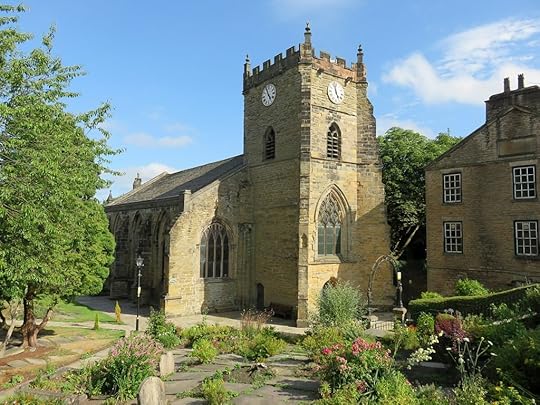

Church of St Thomas the Martyr Up Holland

Church of St Thomas the Martyr Up Holland

In reporting on the Upholland Ghost, the press rarely passed up an opportunity to make fun of the Lancashire accents of the people they interviewed. One of the three Winstanley brothers (the eldest, who was 20 years old) was asked how he felt about the disturbances. ‘Aw wur freetened at fust,’ he told the journalist, ‘but aw’m geetin’ used to it.’[i]

The noise from the nocturnal crashing of mortar and stones could supposedly be heard from 60 yards away, and as word spread of the strange happenings, the villagers began to congregate every night in the graveyard hoping to witness some ghostly activity.[ii]

Ghostbusting Councillors

And if there’s something strange in your neighbourhood, who’re you going to call? Well, in this case, the council. Councillor Baxter, on hearing of the commotion, decided to put together a team of investigators made up of himself and two other local councillors, Mr Bibby and Mr Lonergan. The three of them spent several nights in the haunted chamber, where the Winstanley boys slept. It’s unclear from the accounts whether all three boys slept in the same room – or even in the same bed), but for several weeks they were joined after darkness by intrepid ghost-busting councillors, visiting spiritualists, journalists and the curious who were invited up to witness the unseen agency hurling masonry and other objects around the small room.

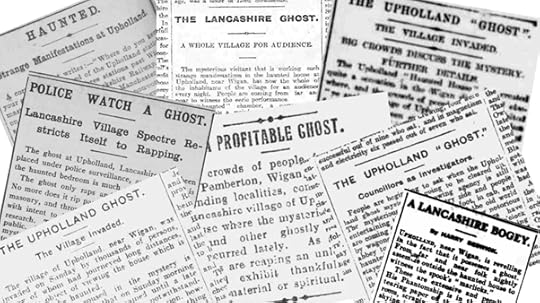

1904 headlines about the Up Holland Ghost

1904 headlines about the Up Holland Ghost

The mysterious missile hurling only occurred after dark, which may have aroused suspicion in some sceptics. The three brave councillors, however, knew better and were convinced the Winstanley lads could not possibly be perpetrating some kind of hoax.

This is how Baxter describes what happened as he and the other councillors clutched their flashlight in the silence and darkness of the haunted chamber:

“All at once there is a sound as of trickling water, and this is followed by the mysterious knocking, which seems to travel from one side of the room to the other round the walls. When the knocking has reached the window recess, the stones are pulled out and thrown on the floor…. There was something like a crack in the wall and then a piece of something was sent right across the room. This was followed by paper from the walls being thrown under the bed and bits of plaster being sprinkled up and down the room.” [iii]

On one occasion, one of the councillors was in another room in the house and was hit by a stone thrown from the haunted chamber. This was surprising as the stone would have needed to make a mid-air right angle turn before it bounced off his head. The councillor dashed into the room, clasped his hands in prayer and declared, ‘In the name of the Lord, speak!’[iv] The ghost remained dumb.

According to the Daily Mirror the ghostbusting councillors kept watch in the haunted chamber for eight nights and in that time didn’t see any evidence that the three lads who slept in the room were causing any of the mischief.[v] And these clever, important men could never have the wool pulled over their eyes by three lower class youths, could they?

Ghost Hunting Flashmobs

The ghostbusting councillors had to admit defeat. Having ruled out trickery, they were convinced something uncanny was occurring, but couldn’t get to the bottom of it. They did, though, keep some of the stones they had been pelted with as ghostly relics of their encounter with the unknown at the haunted house by the cemetery. One of the stones was even displayed at a local shop to satisfy the visitors who were descending on Up Holland as the story spread.

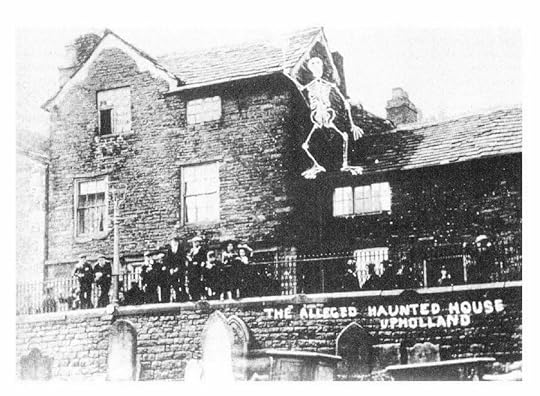

The Haunted House by the cemetery (Alan Miller)

The Haunted House by the cemetery (Alan Miller)

Police Sergeant Ratcliffe also visited the Winstanleys and spent time in the haunted chamber and he concurred with the councillors: this ‘hubbub’ could not have been caused by human agency.[vi]

The house became a ‘Mecca’ for psychic investigators from far and wide, as the Manchester Evening News put it. Mediums and spiritualists visited the haunted chamber but could not lay the ghost.

But the most numerous of the ‘psychic investigators’ were those gathered below the window of the haunted chamber in the cemetery. They came in their hundreds from Wigan and other nearby towns, with entrepreneurial locals putting on waggonettes to carry the curious up to the village. The newspapers spoke of the village being ‘invaded’.

These unruly ‘ghost flashmobs’ as I call them were a strange feature of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Rumours of a haunting would attract huge crowds who would proceed to get drunk, make ghostly noises, prank and scare one another through the night in a riotous impromptu party-cum-ghost hunt. As happened in Up Holland, the police would often lose control as the crowds got larger night by night and more people turned up for spooky, inebriated and riotous fun in the dark. The fact that Up Holland’s haunted house had a pub on either side of it was most convenient, and the landlords were selling out of beer. One of these pubs, the White Lion, still operates in Up Holland.

By early August the crowds of drunken ghost hunters in the cemetery numbered over a thousand. Many, hoping to provoke some ghostly activity, threw their empty bottles at the house. In fact, the gathered throng were so rowdy that the spiritualists trying to make contact with the unseen agency complained that the crowds were noisier than the ghost.[vii] There was concern that the ‘roughs and larrikins’ that assembled and ran riot in the graveyard were doing more damage to the house than the obstreperous poltergeist.

Extra police were called in as around two thousand people filled the graveyard in August, drinking, shouting, sharing ghost stories, screaming and at times hurling their empties at the beleaguered house. The bobbies were said to be trembling as they tried desperately to get the unruly ghost hunting mob to move on.

On the evening of Monday 15 August, a gas lamp in the churchyard was lit by police order and this cast light into the haunted chamber. The pale beam of the gas lamp was enough to scare away the troublesome unseen agency, and the ghost went quiet. The crowds of ghosthunters, however, did not. They continued to gather in the hundreds and sometimes thousands in the graveyard for several weeks afterwards.[viii]

The King of the Robbers

There were several theories offered to explain the strange poltergeist activity in the house by the cemetery. Some suggested supernatural solutions to the mystery while others came up with naturalistic explanations of varying degrees of plausibility.

For those looking for a ghostly culprit for the flying masonry, the first obvious suspect was the spirit of ‘highwayman’ George Lyon whose grave was situated under the window of the haunted chamber. Lyon, the self-styled King of the Robbers, was not your dashing dandy highwayman of historical romance, being more of an inveterate thief, mugger and burglar. Besides, he didn’t have a horse.

George Lyon – the Up Holland ghost?

George Lyon – the Up Holland ghost?Despite being transported to Africa for seven years for his crimes, when he returned to his home village of Up Holland he soon fell back into his criminal ways. He seems to have been an arrogant man, boasting that there was no rope that could fit his neck. He also had a way with the ladies. Two neighbouring houses in Up Holland were occupied by a mother and her daughter in each home. All four of them became pregnant around the same time. The father of all four babies was said to be George Lyon.

After a string of successful robberies with his gang of mates David Bennett and William Houghton, Lyon eventually fell victim to a sting operation. The Upholland village constable, tired of Lyon’s criminal antics, called in John McDonald, a famous ‘thief taker’ from Manchester. A thief-taker was what we might nowadays call a cross between a bounty hunter and a private detective.

McDonald disguised himself as a pedlar, and using his knowledge of criminal slang, became friendly with Lyon, who soon fell to boasting of his criminal exploits. McDonald offered to buy some silver Lyon had recently stolen and paid him in marked bank notes.

Lyon had fallen straight into the trap and was soon arrested, and along with his two partners in crime, hanged at Lancaster on 22 April 1815. The grim job of carting the dead criminals back to Up Holland for burial fell to the landlord of the Old Dog Inn, Simon Washington who later swore he would never do anything like that again, as he was convinced the Devil had followed him every step of the way home.

He was also followed by crowds numbering in the thousands who squeezed into the churchyard to watch his burial. His grave still stands opposite the White Lion, though the name of his daughter Nanny Lyon is all that is visible on the flat stone.[ix]

Grave of George (and daughter Nanny) Lyon

Grave of George (and daughter Nanny) Lyon

Given the proximity of Lyon’s tomb to the haunted chamber, and the romantic legends that inevitably became attached to the profligate thief, it’s understandable that some of the inhabitants of Up Holland were convinced that the ghostly goings on in the house by the cemetery were caused by the restless spirit of George Lyon, perhaps still guarding a stash of long forgotten treasure.

The Unseen Agency

Others suggested that the ‘unseen agency’ was none other than Mrs Winstanley’s late husband. The Daily Mirror reported that before his death, Mr Winstanley had threatened to come back as a ghost to prevent anyone else becoming the new head of the house.[x]

One of the ghostbusting local councillors offered a different explanation for the strange occurrences. ‘Aw burlieve as ‘ow it’s a judgement,’ he told the Clarion newspaper. It was a warning from God against the evils of gambling as one of the Winstanley lads had been betting his money on the horses.[xi]

As for non-supernatural explanations for the flying stones and crashing mortar in the haunted chamber, some suggested there was an army of rats behind the walls, though rodents are not known for their stone throwing prowess. Some wondered if there was an escaped lunatic hiding in the chimney, though searches revealed nothing.[xii]

An electric battery powered device hidden in the chimney and triggered remotely was another unlikely explanation offered. Some said perhaps there were forgotten underground passages beneath the house making the walls unstable, or that passing traction engines were causing the destruction. None of these rationalisations were very plausible.

Plastered

Of course, many suspected it was all a hoax on the part of the family, or at least of the boys. It certainly seems suspicious that the poltergeist activity stopped suddenly when the room was illuminated. Perhaps the boys had a stash of stones within reach under the bed to throw around the room after dark, and maybe they used a stick hidden in the bed clothes to knock stones off the wall from a distance.

In any case, it was noted that many shops were doing extremely good business selling provisions to the masses of ghost hunters turning up every day, and during evening hours the pubs were doing a roaring trade. In fact, some wondered if one of the pub landlords was in on the hoax as they were the ones who benefitted most from the influx of thirsty haunted house tourists. One landlord told the London Daily Chronicle that he hoped the ghost’s antics would continue until judgement day. The landlord of the other pub commented that he wished the ghost had a twin.[xiii]

Taking advantage of the lull in ghostly destruction, Mrs Winstanley employed a plasterer to fix up the crumbling walls of the ghostly chamber, but it wasn’t long before the spook got back to work, this time on another part of the wall. Crowds continued to come in the hundreds through September to see the haunted house.

Two men, Matthias Gaskell and Henry Heyes, found themselves in court charged with being drunk and disorderly on the night of Sunday 14 August. They had, apparently, refused police orders to move on during one of the busiest nights in the graveyard, though perhaps the pair were being made an example of, or were being made scapegoats for the police’s loss of control. Gaskell was found guilty and fined a shilling. Heyes pleaded not guilty and charges against him were eventually.[xiv]

Over the following weeks, the crowds melted away and the ghost ceased his antics. This is often how these episodes end. Nobody ever confessed to hoaxing the ghostly phenomena and the haunted house was finally demolished in 1934, taking whatever secrets it held with it.[xv]

The Skriker in Up Holland

At the time of the events of 1904, some of the older residents of Up Holland remembered similar scary episodes occurring in the very same house in the middle of the nineteenth century. On this occasion, the villagers had been terrified by a skriker, a phantom that usually takes the form of a fearsome black dog. The word skriker comes from the Lancashire dialect word for shriek or scream, and like the Irish banshee, to hear it is a sure sign of imminent death.

In 1904, Up Holland’s oldest resident, Richard Hollowell (84) told the story of the Up Holland skriker to a Wigan newspaper. When Richard was a young man, the village was disturbed every night by a ‘weird and blood-curdling din’ after the sun had set. The ‘unearthly moan’ seemed to be coming from the vicinity of the house by the cemetery, or rather one of the pubs, though it was just a private residence at this time.

The Skriker probably looks a bit like Zoltan Hound of Dracula

The Skriker probably looks a bit like Zoltan Hound of Dracula

Nobody knew what the skriker looked like, but it was enough to hear its ghostly cries echoing round the gravestones and the ruined priory. The deathly wailing terrified the locals who stayed off the streets after dark for fear that the skriker’s fearsome howl was meant for their ears.

One old lady, though, had had enough. She decided to confront the skriker – whatever it was – that had been disturbing village’s peace. She left her house after dark and followed the howling until she came to the houses overlooking the graveyard. As she looked up, in the starlight she saw the man who lived in one of the houses standing by the bedroom window with a curious looking horn pressed to his lips. The dismal din that the villagers took to be a portentous hellhound was actually a man blowing a horn.

The next day the old woman confronted the man and informed him that the game was up. ‘If you will go out of the country,’ she told him, ‘I shall say no more about it.’ The man did indeed leave the country and was never seen again.[xvi]

This, in any case, is how old Richard Hollowell remembered events. Of course, as an octogenarian, he’s earned the right to embellish his anecdote as everyone does, but the fact that other elderly residents of Up Holland mentioned something similar suggests that the core of his memory is true.

But it turns out that this small Lancashire village has yet more mischievous spirits up its sleeve…

Epilogue: The Spectral Funeral Procession

Winters were harsh in Up Holland in the early nineteenth century, and coal was expensive. Freezing to death was a real and all too familiar danger. But as well as this dismal prospect, there was also a new terror haunting the village: a ghostly funeral possession in which the bearers and the mourners were all dressed in white. Even the coffin they carried between the gravestones in the churchyard was white in colour. This was attested to many a person leaving the pub after dark, and this strange sight must have been uncanny indeed.

Eventually, some brave souls decided to investigate and hid near the churchyard as night fell. Sure enough, the ghostly funeral procession carrying the white coffin made its way slowly between the gravestones. Instead of running, though, the brave young men approached the figures in white who immediately dropped the coffin and ran for the hills. To their surprise, the white coffin did not contain a corpse on its journey to its final resting place. It was full of coal.

It turns out, so the newspaper reports inform us, that times were so hard that a gang of men had taken to stealing coal, but rather than risk carrying it through the street, they hit upon the ruse of pretending to be a ghostly funeral procession…[xvii]

I can’t help thinking that if you’re going to steal coal, dressing all in white is the last thing you’d want to do…

In any case, the small village of Up Holland in Lancashire has a fantastic tradition of ghost hoaxing that lasted for a century.

For more ghost hunts, ghost hoaxes and ghost panics, but with a festive theme, see my latest book Phantoms of Christmas Past.

Phantoms of Christmas Past

[i] ‘A Lancashire bogey’, Clarion, 26 August 1904, p.1

[ii] ‘The haunted house at Upholland’, Wigan Observer and Daily Advertiser, 20 August 1904, p.8

[iii] ‘The Upholland Ghost’, Norfolk News, 27 August 1904, p.6

[iv] ‘Haunted, strange manifestations at Upholland’, Manchester Evening News, 15 August 1904, p.7; ‘The haunted house at Upholland’, Wigan Observer and Daily Advertiser, 20 August 1904, p.8

[v] ‘Police watch a ghost’, Daily Mirror, 20 August 1904, p.4

[vi] ‘The Upholland Ghost’, Wigan Examiner, 17 August 1904, p.3

[vii] ‘The Upholland Ghost’, Wigan Examiner, 17 August 1904, p.3

[viii] ‘The haunted house at Upholland’, Wigan Observer and Daily Advertiser, 20 August 1904, p.8

[ix] Allan Miller (1964) ‘Geroge Lyon: Highwayman’, Historic Society of Lancashire & Cheshire Journal, vol.116 pp.235-241. Available at: https://www.hslc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/05/116-12-Miller.pdf

[x] ‘Police watch a ghost’, Daily Mirror, 20 August 1904, p.4

[xi] ‘A Lancashire bogey’, Clarion, 26 August 1904, p.1

[xii] ‘Haunted, strange manifestations at Upholland’, Manchester Evening News, 15 August 1904, p.7;

[xiii] ‘Ghost resumes work’, London Daily Chronicle, 29 July 1904, p.1

[xiv] ‘The Upholland Ghost’, Wigan Examiner, 27 August 1904, p.8; ‘The Upholland Ghost: a sequel’, Liverpool Daily Post, 10 September 1904, p.3

[xv] Andrew Miller, (2004) ‘The Ghosts of Upholland’, Past Forward, no 36 pp.6-8. Available at: file:///D:/Blog/Upholland%20ghost/mil...

[xvi] ‘The skriker in Upholland’, Wigan Observer and Daily Advertiser, 7 September 1904, p.5

[xvii] ‘The Ghosts of Upholland’, Dundee Courier, 23 March 1912, p.8

May 13, 2025

Green Whiskers: The Shetland Sea Monster

“It made the very hairs on our heads stand on end for fear…”

A monstrous creature with green eyes, long green whiskers and a cavernous mouth haunted the waters round the Shetland Isles in the late nineteenth century. In May of 1882 a boat of fishermen had a terrifying encounter with this monster of the deep and it caused a media sensation. The monster has no name, so I’ve taken the liberty of calling him Green Whiskers.

What was this strange creature? Could it have been the mysterious creature from Shetland folklore, the bregdi? Or is there another mega mouth monster lurking in our shores?

Green Whiskers

The fishing boat the Bertie Goudie was about 28 miles east-southeast of the northern Shetland Isle Fetlar on a cloudy but fine morning on 18 May 1882. The crew had every reason to be confident of a good catch – they frequently returned to shore with more impressive hauls than did their rival fishing boats. The fifty foot sailing boat was manned by half a dozen men, and their regular success meant they had a good reputation among the local community.

Shetland Yawl (Holdsworth 1874)

Shetland Yawl (Holdsworth 1874)As the men were hauling in their fishing lines, they saw in the distance what appeared to be three hills, each the size of an upside down six-oared boat. Something blew out of the water and the fishermen thought there must be three whales following each other. When the three hills sank under the waves, the crew saw to their horror that it was not three whales but one huge creature, and it was heading straight for them, possibly attracted by their haul of fish.

Some of the men rushed to the side of the boat and saw the monstrous beast pass under their fragile little boat. ‘I can tell you,’ one claimed, ‘it made the very hairs on our heads stand on end for fear.’

One of the men wanted to cut the lines and sail for the nearest shore, but the skipper had not seen the creature and wouldn’t allow it.

The creature surfaced again, allowing the astonished crew to get a good look at it. It had a monstrous gaping square jaw with an underlip that was four or five feet deep. Bizarrely, it had what appeared to be whiskers of a ‘pretty’ green colour that were seven or eight feet long hanging from its mouth. Its head was covered in gigantic barnacles the size of herring barrels, and its skin was crusted in marine slime and filth.

The skipper ordered the men to scream as loudly as they could and throw stones and lumps of old metal used for ballast at the monster, hoping to scare it away, but in vain – the objects bounced off its head like marbles and the creature was still heading straight for them. Its mouth was big enough to swallow the whole boat and crew with ease. Its two huge fins were as large as the boat’s mainsail and flapped horribly above the water. They estimated the creature was 150 feet long, three times the length of their boat. For context, the longest blue whale ever measured was 98 feet long.

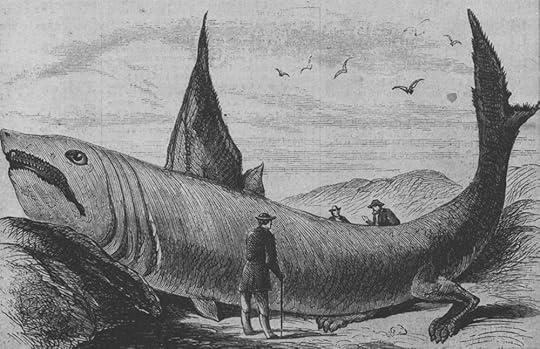

Green Whiskers as imagined by the Illustrated Police News

Green Whiskers as imagined by the Illustrated Police News

When the creature was only a few yards from the boat, one of the crew grabbed his shotgun and fired both barrels into the monster’s gaping maw and this seemed to stop it. The skipper ordered their fishing lines cut and the sail was hastily raised. The boat caught a gust of wind just in time to avoid the monster which burst out of the water in their wake. A few seconds’ delay, and the Bertie Goudie would have been destroyed.

They sailed as fast as their boat would carry them, with the creature pursuing them at 100 yards distance. The skipper tried to sail the boat in a zig-zag manner to confuse the monster, as for three hours and eleven miles it hunted the terrified fishermen. Eventually, they lost it and returned to shore without their expected brimming nets and had to explain how they had lost a mile of fishing lines.[i]

The episode was written down and signed by the (unnamed) skipper on behalf of his crew and was printed in national and local press around the country – sea monster tales were fairly common in the press in the nineteenth century, and were usually treated with scepticism and mockery, or as a kind of fun silly season story.

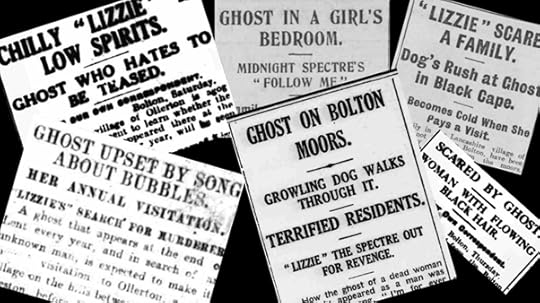

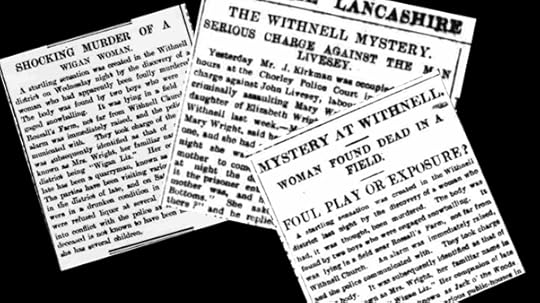

Some newspaper headlines from June 1882

Some newspaper headlines from June 1882

The Bregdi

So what did the crew of the Bertie Goudi encounter? From their description it sounds very much like the dreaded Bregdi, an uncanny, semi-mythical creature said to haunt the waters around the Shetland Isles. Like Green Whiskers, the Bregdi has huge fins, the size of a boat’s sail, and if it saw a boat would often attack it, dashing it to pieces with its sharp fin, or even worse, wrapping its fins around it in a deadly embrace before pulling the hapless ship and all who sail in it to a watery grave at the bottom of the sea.

This weird whale-like monster was much feared by Shetland fishermen who thought it the most dangerous of sea creatures. They would try and appease the monster by throwing coins or pieces of iron overboard as an offering to him. Tradition also says that the Bregdi is terrified of amber beads, and a single bead thrown at it would be enough to keep it at bay.[ii]

The Bregdi is now thought to be the basking shark, something Shetland fishermen would have encountered. This species of whale shark is the biggest fish of the British Isles, and the second largest shark in the world – it can grow to over 30 feet. They are known to bask on the ocean surface as they feed, and although they’re pretty slow they can and do leap out of the water. The basking shark’s most distinctive feature is its huge mouth with long gill rakers, used to filter the plankton it feeds on.

Could the men on the Bertie Goudi in 1882 have encountered a basking shark? It certainly had a huge mouth, and perhaps the green ‘whiskers’ the men observed were in fact shark’s gill rakers. In the image below, you can see how the gill rakers could be taken for long whiskers, especially when in a state of panic and confusion as the men were.

Basking shark opens up (Chris Gotschalk)

Basking shark opens up (Chris Gotschalk)

The Shetland monster was said to be 150 feet long, which is much longer than even the biggest known basking shark. Anglers have a reputation for exaggeration, though in the case of the Bertie Goudi, it was the fishermen who were the ones that got away.

Jumping the Shark

However, basking sharks are tiny brained mellow creatures, so the apparently aggressive behaviour of Green Whiskers is puzzling. Basking sharks are often characterised as sluggish gentle giants floating around and filtering plankton. They have, though, been known to kill – in 1937 a huge basking shark breached the surface at Carradale Bay, Kintyre destroying a boat and drowning three people. Many other sharks had been seen breaching in the vicinity.

It’s unclear why basking sharks breach – leap out of the water. One suggestion is it rids them of parasites. Another idea is that it’s courtship behaviour or a display of aggression or some other kind of communication. In any case, recent research has found they can swim at over 5 metres per second and jump over a metre out of the water, comparable to great white sharks. This makes the Shetland fishermen’s fear of the bregdi understandable and what gave the creature its fearsome reputation.

This leads me to wonder if the fishermen on the Bertie Goudie had actually been surrounded by basking sharks breaching, and that they had seen not one shark but several different ones leaping out of the water at different times which they mistook for the same creature pursuing them. Perhaps the sharks weren’t being aggressive, they were just doing their mysterious shark business of leaping out of the waves.

There’s also the possibility that it was all a joke or prank played by the fishermen, and perhaps an excuse to explain away the loss of their fishing lines. Although the fishing boat Bertie Goudie definitely existed and its crew were well known in Shetland, the many newspaper reports give no names. Nineteenth century newspapers – like present day ones – were happy to print exciting but spurious stories.

Epilogue

Basking sharks have been at the centre of a number of strange stories. One of the strangest occurred in Eastport Maine in October 1868 when a 30 foot ‘wonderful fish’ washed ashore. Its mouth was five or six feet wide and had hundreds of teeth, as do basking sharks. Strangely, this beast was said to have two legs with webbed feet near the back of its body, as illustrated in Harper’s Weekly below.[iii] Crowds came from far and wide to witness the strange hybrid sea monster.

The ‘Wonderful Fish’ caught in Maine 1868 (Harper’s Weekly 24 October 1828)

The ‘Wonderful Fish’ caught in Maine 1868 (Harper’s Weekly 24 October 1828)

The ’legs’ were quite probably the shark’s reproductive organs or ‘claspers’ – yes, you could say it has two penises – which look a little like webbed feet.

Anyway, my guess is the fishermen of the Bertie Goudi accidentally found themselves surrounded by basking sharks who were breaching and then gave their adventure a bit of additional colour – and size – in the retelling.

For more fishy tales about sea monsters, see here:

Slippery Sam ~ Yorkshire’s ‘Nessie’

Attack of the North Sea Monster!

[i] ‘The monster of the deep’, Glasgow Herald, 2 June 1882, p.9; ‘The sea monster at Shetland’, Northern Ensign and Weekly Gazette, 8 June 1882, p.8; ‘Encounter with a sea-monster’, Illustrated Police News, 10 June 1882, pp.1-2